Blind conformity can be very dangerous especially when it comes to managing your company’s talent. In this article, the author elaborates on why and how reward for performance fails to deliver its objectives, how there is no one size fits all when it comes to employee reward, and why alignment to strategic priorities is key to organisation effectiveness.

Few executives in the firms I work with are completely happy about how they reward their people. Attracting valuable talent, engaging staff and securing positive behaviour remains as challenging as ever. Worse still, reward is often blamed for misdirected employee effort, dysfunctional behaviour, disengagement and energy sapping conflict. These firms, like the clear majority across industry, reward their people based on performance.

For decades, a plethora of books, articles and consultants’ reports have espoused the bottom-line benefits of rewarding for performance – such as using individual bonuses or merit based pay increases – to align employees’ financial interests to those of their employer. Firms have rushed to embrace the unitarist logic of reward (also referred to as pay, compensation or remuneration) for performance for all sections of the workforce, and not just executives. A 2013 survey of more than 350 publicly traded companies in the US revealed that all (99%) use some form of short-term incentive (bonus) plan for their broad-based employee population.1 The proportion of UK organisations in 2013 operating performance-related financial reward, incentive and recognition schemes was 77% in private sector services and as high as 92% in very large and multi-national organisations.2 The consultancy, Willis Towers Watson, puts the figure even higher, with 94% of organisations using some form of annual bonus or short-term cash incentive.3 Individual performance is the most important criterion for determining base pay progression for the majority (74%) of companies, and individual bonuses the most prevalent form of financial incentive (66%), in the latest survey (2017) of UK reward management practice by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.4 Reward is no longer simply the cost of hiring necessary labour, as it once was. It is a management tool for securing strategically valuable employee outcomes by attracting key talent, fostering desirable behaviour and maximising employee and firm financial performance. Reward for performance is the dominant logic of how firms remunerate their people in the contemporary workplace.

Armies of consultants and career remuneration managers are employed to ensure reward for performance does exactly what it says on the tin. But does it? Reward for performance has become associated with bad business in recent years. Banking bonuses have been routinely blamed in the media for the excessive risk taking that precipitated the global financial crisis. Investors and the public alike continue to heap scorn on dramatic increases in executive pay despite lack of commensurate increase in firm performance. In these economically austere times, high value bonus awards are instantly front-page news amidst cries of corporate greed. Governments and regulators have moved to place caps on the value financial incentives awarded to staff to curb reckless behaviour, implying in the process that companies (banks especially) can’t be trusted to manage their own remuneration arrangements responsibly.5 Within research literature, establishing a positive link between company performance and the deployment of performance based reward practices remain elusive. Doubt over the benefits of reward for performance is growing.6 Many call for the decoupling of performance and reward altogether.7 Rewarding performance, it seems, is risky business – there are significant economic, social and reputation risks to getting it wrong. Why are attempts to reward for performance not delivering expected results? What could firms do differently to de-risk their reward practices and manage them better for strategic value in future?

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Reward is Risky Business

As we experience a period of relative economic stability and a resurgent focus on maximising firm financial performance, ten years on from the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, this article offers insights about the effectiveness of reward for performance by drawing upon research and experience from the last period of economic confidence and stability.8

Controlling for industry effects, the multi-year programme of research explored in-depth how seven leading consumer perishable goods firms competing internationally managed reward for performance as part of a wider strategic human resources agenda. At the time of the research (2002-2007), their combined annual global sales exceeded USD$160 billion and they employed collectively over 560,000 staff worldwide. In all cases, spend on employee reward constituted the largest single operating cost. All firms operated in multiple international locations, with one firm operating in over one hundred and twenty locations throughout the world. All were large, established and well resourced. All were household names with their brands dominating the global perishable goods marketplace (e.g. food, beverage, confectionary, household products and tobacco).

The research reviewed reward arrangements of all grades and occupations of employee below board level and above shop floor level. Over 150 interviews were conducted with senior executives, people managers and HR specialists across a diverse range of international functions and operations within the seven case study companies. The interviews were supplemented by employee workshops, attitude surveys, documentary analysis and additional interviews with retained management consultants.

Rewarding for Performance

All seven firms used a variety of reward for performance schemes to reward a considerable majority of their managerial, technical and professional employees – the bulk of their workforces. The degree of employee reward “at risk” (based upon performance) differed across all seven firms for comparable roles, but increased drastically in all cases with employee seniority. All seven firms professed to view reward for performance as a strategic tool to leverage employee effort and secure strategically desirable behaviour. In all cases, concerns over firm financial performance informed the choice to use reward for performance mechanisms to remunerate employees. Reward for performance was viewed as a powerful tool in the management arsenal to drive high levels of employee performance that could not be achieved easily through alternative methods. At considerable expense, all firms employed full time and dedicated remuneration specialists within their human resources departments.

Reward Failing to Deliver, And Worse

The multi-year research programme revealed all seven case study firms struggled to manage reward for performance in line with their aspirations. In two of the seven cases, the gap between intended policy and operational reward practice was relatively small, because the management of reward for performance was largely devolved to line managers. Line managers were good at managing reward systems of their own design. In cases where reward for performance systems were corporately designed – by headquarters HR staff for example – there was evidence of wide variation between espoused policy and what was implemented at the coalface.

For a variety of reasons, line managers didn’t manage employee performance in line with corporate policy, or via the formal management process, thereby limiting the effectiveness of the linkage to corporately desired reward outcomes. Reward for performance schemes were not typically the driver of positive behaviour envisaged by headquarters staff. This was especially true in cases where incentives, for example, were corporately mandated but felt to be a poor fit for the culture of the local workplace. They were often adapted or rejected by line managers, unbeknown to headquarters staff. Corporate-wide reward for performance cannot be effective if it is not being implemented as intended. We know what companies say they do, but they don’t always do what they say.

Worse still, individual accounts of attempts to implement reward for performance across all seven case study firms revealed numerous examples of unintended and negative consequences. Negative outcomes included misdirected staff effort and behaviour, high staff turnover, disengagement and elevated workplace conflict. The negative impact of ineffective reward for performance schemes was often discreet, especially in cases with a high-power distance between those designing performance based reward systems, such as the corporate human resources department, and line managers tasked with their implementation within operational business units. The consequences were all too real and all too immediate for those at the front-line. Employee reward is an emotive subject – ask any manager and they will say it is easier to get it wrong than it is to get it right. When wrong, it is difficult to remedy the damage arising from the perceived unfairness of mismanaged reward. Why were these attempts to reward for performance failing to deliver, or worse?

Failing to Align Reward to Strategic Priorities

Designing and managing reward for performance is extremely technically challenging. Its sheer technical complexity and difficulty goes a long way to explaining why poorly designed and managed reward systems can easily produce unintended and value destroying outcomes. There are other less obvious, but equally important, reasons to consider.

Firms Struggle to Align Reward to Strategic Priorities

A major challenge to the effective design and management of reward for performance within several case study firms was an absence of understanding about the strategic priorities of the firm. Reward decision makers were often unclear about the strategic function of the reward systems they were tasked with designing and therefore struggled to select the appropriate technical form for implementation.

Conceptually, reward for performance is located within a value chain, which connects corporate strategy to employee outcomes in the form of resourcing requirements (attraction and retention of valuable talent), motivation (securing effort and productivity) and positive behaviours (necessary to implement the strategy).9 For instance, firms seeking to outcompete their peers on the basis of innovation (e.g. new products) will seek to attract the best available talent according to their knowledge, creativity, long-term focus and potential to work free from supervision.10 Such discretionary effort would be highly undesirable for firms seeking to compete on the basis of cost minimisation. Desirable cost competition employee outcomes include error minimising behaviour, cost-consciousness, a short-term performance focus, diligence and compliance with highly routinised behaviours to maximise efficiency. It was apparent that reward for performance systems often failed to produce desirable employee outcomes because the strategic ends were not well understood by those responsible for reward system design and implementation. A lack of strategic direction, and too few parameters against which to balance complex managerial trade-offs, resulted in high levels of uncertainty for all concerned – HR, line managers and employees alike.

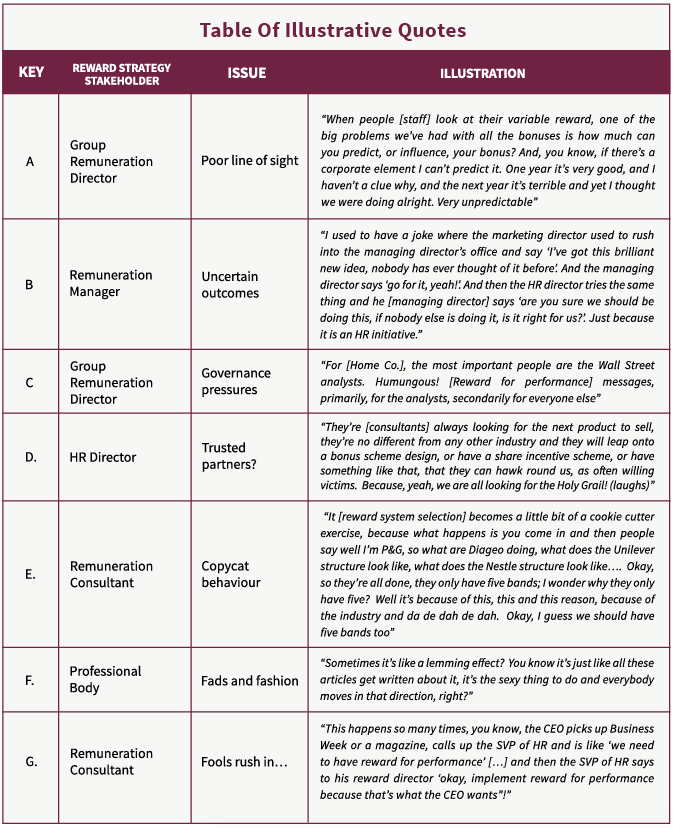

In the absence of understanding the strategic context, those with responsibility for making reward decisions were understandably risk averse in their choices. Very few attempts were observed within the case firms to identify new or creative ways in which to reward their people in support of firm strategic priorities. Innovation was simply not on the agenda. On the contrary, given the potential negative consequences of poor reward decision-making (e.g. employee dissatisfaction), every attempt was made to avoid getting it wrong – including choosing the path of least resistance with regards to stakeholders, or simply doing nothing new. It would be expected that as firm strategic priorities shift in response to new competitive threats, changing customer preferences and regulation, so too should a firm’s reward strategy if it is to remain aligned and capable of producing employee outcomes of strategic value. There was little evidence of creative attempts to introduce differentiated reward systems in step with strategic change, or anything that wasn’t a known quantity (see illustrative quote B).

Further in evidence was intense pressure to adopt reward for performance for reasons other than securing strategically valuable employee outcomes. In some cases, it was simply to send signals to investors and markets about the commitment of the firm to improving their financial performance. For example, in one US headquartered firm, linking reward and performance was an important element of instilling confidence in investors (see illustrative quote C).

Legitimacy is Prioritised Over Strategy in Reward Choices

The desire for legitimacy amongst peer firms exerted a powerful influence over the choice to adopt reward for performance. Reward managers within each of the seven case study firms participated in an invitation only “Industry Club” (the Club). Hosted by individual members on a rotating basis (and often at the host’s offices), the Club met regularly (often quarterly) to review general trends within their industry and reflect on common challenges and new techniques. The Club allowed reward professionals from different companies to compare their thinking and current practice against their peers in a benign environment. More importantly, members of the Club sponsored and participated in a yearly salary survey to establish median and quartile market rates in a like for like comparison of key roles and occupations. Without knowing what specific peer companies paid – these often being direct competitors – these data provided external salary benchmark data on a role-by-role basis. An independent third party, always a major remuneration consultancy during the term of the research, administered the salary survey. Consultancies gathered, analysed and disseminated the results supplemented by insights from their own experiences with clients (often individual members of the Club). As a valuable source of fees and a network for new client business, there was intense competition between different consulting houses to serve the needs of the Club.11

These same consultancies also simultaneously advised several individual Club members on reward scheme design and governance. Both directly and indirectly, management consultancies exerted huge influence over the reward decision-making process of individual Club members and, by extension, the industry (in this case, perishable consumer goods). Direct influence took the form of consulting services relating to reward design and workforce management. Indirect influence arose from the dissemination of research reports, opinion pieces, the hosting of themed conferences and networking events. These events were considered valuable marketing opportunities to promote new consulting services and build client relationships. Clients were not oblivious to the influence of consultancies on their internal processes (see illustrative quote D). Nevertheless, in addition to valuable technical input, the use of external consultants as a source of external expertise enhanced the perceived legitimacy of their clients’ reward choices, especially in the eyes of their internal stakeholders. The more prestigious the consultancy house, the more legitimate the process, or so the logic seemed to go.

Such clubs are not limited to the industry under study. They exist for the purpose of sharing experiences with fellow professionals, finding support and establishing relative benchmarks with those considered to be peers (and therefore desirable comparators). Inevitably, it is not simply salary levels that are compared, but reward practices as well on the basis of “you show me yours and I’ll show you mine”. As a result, these clubs act as a powerful mechanism for generating industry norms or “best practices” as Club members commonly refer to them. These norms become institutionalised and highly influential as the industry standard.12 Despite the absence of collective representation of employees’ interests, the sample firms were voluntarily setting rates for reward in a way that was reminiscent of co-ordinated industry-wide collective bargaining of the previous century.

Industry wide reward norms, such as those created and maintained by the Club – and in this case reward for performance specifically, were binding for those firms wishing to be competitive within the labour market, both in respect of what they paid (i.e. how much) and how they paid (i.e. the mix of reward components, including incentives). The result was mass standardisation of reward practice at the industry level, and not managerial differentiation and distinctiveness at the company level i.e. how firms chose to pay their people was virtually identical across the industry. Individual firms were choosing to conform to industry norms instead of attempting to formulate their own unique strategically aligned reward systems. Conformity was the result of firms emulating what was perceived to have worked elsewhere on the presumption it would work equally well for them (see illustrative quote E). The perishable consumer goods industry was replete with fads and fashions, all of which exerted a powerful influence over reward system selection at the company level, as noted by a management consultant simultaneously serving multiple members of the Club (see illustrative quotes F and G).

Deviating from “legitimate” norms – or bucking the industry trend – was especially difficult for firms to justify in the face of intense competition for talent and/or poor corporate performance. Moreover, conforming to legitimate industry norms served a very practical purpose for those responsible for making reward related decisions. By adopting what was considered industry “best practice”, it was easier to defend their choices to their superiors, irrespective of whether the outcomes were good or bad for the company. All these factors combined explain the startling conformity of reward practice observed across the seven firms – they strongly exhibited herd behaviour. They moved in co-ordinated formation as they carefully picked a path between volatile market forces, threatening regulation and the increasingly activist demands of institutional shareholders, using legitimate reward norms for shelter.

The implication is that, despite rhetoric to the contrary, industry norms exerted greater influence over the form of case study firm reward practice – in this case the design and management of reward for performance – than attempts to secure strategically distinctive employee outcomes.13 Put simply, reward for performance was not selected, designed or managed to be strategically aligned.14

Five Principles for De-risking Reward

This article has attempted to explain why the dominant logic of rewarding employees for performance can backfire, producing unintended and potentially negative outcomes in the form of misdirected employee effort, disengagement and value destroying behaviour. Reward for performance often fails to create expected value because it is not aligned to what is valued strategically, for a myriad of reasons, many of which are institutional and social in nature. Aligning strategy, employee outcomes and performance through reward systems can be made to work better if firms embrace the following principles:

1. Reward systems should be as distinctive as the strategies they support: Context is king in reward determination, and yet we see far more similarity of reward practice between firms than we see differences. Firms are choosing to conform and there is little in the way of distinctiveness. This is especially the case when decision makers mimic the reward practices of competitors and fashionable firms, in lieu of attempting to align their reward choices to support their own business strategy.

2. There is no one size fits all solution for the whole organisation: The findings indicate one size fits all reward for performance systems are the most problematic to implement and produce the greatest number of unintended and negative consequences. To be effective, reward systems need to be designed carefully to support the strategic direction of the firm overall and each of its individual operating components. This requires a much greater appreciation of the strategic and operating contexts into which reward (and reward for performance especially) systems are being introduced, through improved business analytics and participative decision-making.

3. The reward proposition should be as personalised as possible: Firms should strive to tailor employee reward to specific types of work as much as possible. In future, this will require segmenting the workforce less along functional or departmental lines, and more according to the type of work being performance irrespective of the formal organisational structure. Different groups of employees should be segmented and their “deal” branded as if they are customers.

4. Work is its own reward to the right talent: The highest paying firms are not the best performing. Organisations should brand the employee experience, and focus on what really matters to the “right” people – the opportunity for intrinsically meaningful work that makes a difference. When attracting and retaining valuable talent, true competitiveness comes from an ability to offer work opportunities that cannot be found elsewhere because they are personalised and meaningful.

5. To improve performance, develop better managers: Reward for performance is no substitute for strong and effective leadership – it can only fail when used as a crutch for weak leadership. Effective reward for performance requires robust performance management at the front line and a culture in which employees are engaged in their work. In place of developing ever more sophisticated, but ultimately mechanistic, reward systems to engage employees in their task, organisations would do better to invest in enhancing the quality of their people managers. The quality of relationship between managers and their people is the single greatest factor in sustainably generating alignment behind the purpose and values of the organisation.

The issues raised here are a pressing concern because the workplace is in a transitional phase.15 As information technology evolves, it is reshaping how organisations are structured, how they learn, how they mobilise knowledge and how they capitalise upon the value of their people as a rare and valuable resource.16 Above all, the ushering in of the “information age” is redefining how organisations will compete in future.17 Organisational boundaries are becoming more porous. Discretionary initiative and creativity is increasingly the result of both human and machine capability. Many organisations are undergoing a process of “deverticalisation”,18 coming to resemble networks more than the traditional hierarchies we already associate with the industrial age. Informal (and often external) relationships will underpin work processes as much as formal internal structures, and much more so for knowledge work.19 Collaboration is already equal in importance to co-ordination and control, as firms strive to become simultaneously innovative and efficient.20 Strategies will have to become more emergent and less planned as the competitive and customer terrain shifts with greater speed – a direct challenge to rewarding for performance against predetermined targets.21

These fundamental changes to work organisation will require equally fundamental change to the ways in which people are rewarded financially for their role in creating and protecting value. It is entirely possible in future that talented individuals and teams will serve multiple employers – or “commissioners” of their talent – simultaneously. This challenge to the notion that employers will continue to monopolise the time of the valuable human capital upon which they rely is another 21st century shock to the already shaky foundational assumptions of reward for performance conceived in and for the workplace of the 20th century.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Author

Jonathan Trevor is Associate Professor of Management Practice at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. His principal research, teaching and consulting interests are the linkage between strategic and organisational priorities and the development of capabilities that give organisations a distinctive competitive edge.

Jonathan Trevor is Associate Professor of Management Practice at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. His principal research, teaching and consulting interests are the linkage between strategic and organisational priorities and the development of capabilities that give organisations a distinctive competitive edge.

References

1. Incentive Reward Practices Survey, 2013, WorldatWork and Deloitte Consulting LLP

2. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, 2013 Annual Reward Survey of UK Industry

3. Towers Watson (2014), UK HR Consultant’s Survey

4. CIPD (2017) Reward Management Survey. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development

5. Slater, S (2013), “Barclays rejigs pay to counter EU bonus clampdown”, Reuters, November

6. Culbert, Samuel A. 2010. Get Rid of the Performance Review!: How Companies Can Stop Intimidating, Start Managing — and Focus on What Really Matters.New York: Business Plus.

7. DiDonato, T (2014), “Stop Basing Pay on Performance Reviews”, Harvard Business Review,January

8. These data were collected in the period 2002-2007, prior to the global financial crisis of 2007-2008. The period was characterised by strong economic performance and relative market stability. Whilst the findings are not representative of practice since 2008, a period of unprecedented economic uncertainty, they provide a valuable illustration for the future marketplace as confidence improves and firms again look to use reward to drive performance maximisation.

9. Lawler, E. E. (1990), Strategic Reward. New York: Jossey-Bass.

10. Schuler, R. and Jackson, S. (1987). “Linking competitive strategies with HRM practices”. Academy of Management Executive, 1 (3): 209–13.

11. Two remuneration consultancies were retained as the annual survey administrator during the term of the research. Both were large international firms headquartered in the United States.

12. Meyer, J. and Rowan, B. (1991). “Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony”. in W. Powell and P. DiMaggio (eds), The New Institutionalism in organizational analysis.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

13.Trevor, J (2011) Can Reward Be Strategic?, Palgrave Macmillan, London

14. Trevor, J & Varcoe, B (2017), “How Aligned Is Your Organization”, Harvard Business Review, February

15. Heckscher, C., Donellon, A. and Applegate L. M. (1994), The Post-Bureaucratic Organization: New Perspectives on Organizational Change, Thousand Oaks, EUA, Sage.

16. Barney, J. (1996). “The resource-based Theory of the Firm”. Organization Science, 7 (5): p. 469.

17. Chesbrough, H, and Appleyard, M. M. (2007). “Open Innovation and Strategy”, California Management Review, 50 (Fall), 57-76.

18. Fishenden, J. and Thompson, M. (2013) “Digital government, open architecture, and innovation: why public sector IT will never be the same again.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(4): 977-1004 (DOI: 10.1093/jopart/mus022)

19. Williamson, P. J. & De Meyer, A., 2012, “Ecosystem Advantage: How to Successfully Harness the Power of Partners” in California Management Review, Vol 55, No. 1 (Fall) ), 24-46.

20. Miles, R, Miles, G, Snow, C, Blomqvist, K and Rocha, H (2009), “The I-Form Organization”, California Management Review, Vol. 51, No.4, (Summer), 61-76.

21. Sidhu,I. (2010), Doing Both: How Cisco Captures Today’s Profit and Drives Tomorrow’s Growth, FT Press, New Jersey