By Simon L. Dolan, Kyle Brykman, Javier S. Casademun, and Miriam Diez Pinyol

Trust, a cornerstone of human relationships, is deeply rooted in neurobiology and essential for effective leadership. Here we explore the neuroscience behind trust, focusing on the role of hormones and brain regions, and consider how knowledge of these mechanisms can be useful to business leaders.

An Overview of the Neurobiology of Trust

The neuroscience basis of trust is a fascinating topic that considers the intricacies of the human brain and its ability to build and maintain strong relationships. Trust is a fundamental aspect of human relationships and is essential for social bonding and collaboration.2 It is a complex phenomenon that involves a combination of cognitive, emotional, and social processes.

The neuroscience of trust is largely based on understanding the brain’s reward system, which is responsible for regulating our emotions and behaviors. Studies have shown that when we trust someone, our brains release several hormones that are associated with social bonding and attachment. The chemical reaction creates a sense of warmth, closeness, and intimacy, which reinforces the bond of trust between individuals.

Furthermore, the prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain responsible for decision-making and social behavior, is involved in this process. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for evaluating social cues and determining whether someone is trustworthy. When we encounter someone who displays trustworthy behavior, the prefrontal cortex sends signals to the reward system, which reinforces the bond of trust.

However, other regions of the brain, such as the amygdala, play a crucial role as well. The amygdala is responsible for processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety, which can impact on our ability to trust others. When we encounter a potential threat, the amygdala sends signals to the prefrontal cortex to evaluate the situation and to determine whether it is safe to trust the other person.

Fundamentally, trust is the result of a complicated interaction between brain circuitry, emotional reactions, and cognitive processes. Recent developments in neuroscience have illuminated the complex processes governing our capacity for trust. Research has shown that when the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is activated, it signifies a person’s willingness to trust others.3 By reviewing research in which trust is a central component, we can better understand the elements of this model and their implications.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown a correlation between levels of trust and activity in the vmPFC; it exhibits increased activity when people play trust-based games, such as the Trust Game. Overall, the vmPFC plays a crucial role in processing trust-related information and influences how individuals make decisions in social interactions.

Understanding the neural mechanisms underlying trust can provide insights into human behavior and relationships (see figure 1), especially in the corporate world.

Figure 1: The brain and the hormones connected to the concept of trust

The Key Role of Oxytocin and Implications for the World of Corporate Work

An important component in the neuroscience of trust is the neuropeptide oxytocin, also known as the “bonding hormone” or “love hormone”.4 Social bonding cues like physical touch, eye contact, and constructive social interactions cause the release of oxytocin, which has been found to enhance trust and promote prosocial behavior.5

Oxytocin has been found to enhance trust and promote prosocial behavior.

The impact of oxytocin on trust is mediated by its interactions with the vmPFC and the amygdala, two brain areas implicated in social cognition. By decreasing amygdala activity, oxytocin lowers fear and increases socially approachable behaviors.6 Furthermore, by making social benefits like cooperation and reciprocity more salient, oxytocin contributes to the development of trust-based relationships.7 These neurobiological mechanisms highlight the interconnectedness between brain regions involved in trust and emphasize the importance of understanding the chemistry and circuitry underlying trust to build and maintain trust when working in modern organizations.8

Figure 2: Oxytocin – the hormone of love and trust

So, in the corporate world, here are some of the key links between oxytocin, trust, and related concepts that affect stakeholders’ behavior, namely the conduct of leaders:

Increased Trust and Cooperation

Oxytocin has been found to promote trust and cooperation among individuals, which can greatly impact leadership behavior. For example, Zak et al. (2004) found that when individuals in a group were given oxytocin, they showed a higher level of trust towards their leader and were more likely to collaborate with others in the group. This may lead to leaders being more inclusive and supportive, fostering a sense of psychological safety within their teams.

Enhanced Empathy and Understanding

Oxytocin has been linked to increased empathy and understanding towards others. For instance, Hurlemann et al. (2010) found that participants who received intranasal oxytocin had a greater ability to recognize and understand facial expressions of emotions compared to those who received a placebo. This implies that leaders who have higher levels of oxytocin may exhibit a greater ability to understand the needs and emotions of their team members, enabling them to lead with more empathy and compassion.9

Improved Communication and Bonding

Oxytocin has been shown to facilitate communication and bonding between individuals. For example, De Dreu et al. (2010) found that participants who received intranasal oxytocin were more likely to display prosocial behavior, such as offering help and support to others, which in turn enhanced group cohesion. This finding suggests that leaders with heightened levels of oxytocin may exhibit stronger communication skills and foster a sense of collective identity within their teams, encouraging collaboration and loyalty.10

Increased Influential Power and Persuasion

Oxytocin has been associated with influencing others and enhancing persuasive abilities. For example, Kosfeld et al. (2005) found that individuals who received intranasal oxytocin were more likely to comply with requests and trust the person making the request. Thus, leaders with higher levels of oxytocin may be more effective in influencing and motivating their team members, leading to enhanced leadership behavior and the ability to achieve desired outcomes.11

Reduced Stress and Conflict Management

Oxytocin has been found to have stress-reducing effects and promote conflict management. For instance, Heinrichs et al. (2003) showed that the administration of oxytocin led to reduced stress responses and improved conflict resolution skills. Their research indicates that leaders who have higher levels of oxytocin may be better equipped to manage stressful situations, maintain team harmony, and resolve conflicts, leading to a more positive work environment.12

The Dopamine System, Trust, and the Implications for the Corporate World

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter, is also essential in determining how actions connected to trust are shaped. Dopamine is well recognized for its functions in motivation, reward processing, and reinforcement learning.13 According to recent research, dopaminergic pathways affect how people anticipate and value social rewards, which likely affects decisions about trust.14 All in all, research suggests that when individuals experience a release of dopamine in their brains, they are more likely to engage in trusting behaviors, which leads to stronger relationships and collaborations. This can contribute to enhanced teamwork, problem-solving, and overall corporate success.

Understanding the role of dopamine in trust can provide insight into how individuals navigate social interactions and form relationships. For example, studies employing neuroimaging methods and pharmacological treatments have demonstrated a correlation between dopamine receptor activation in the ventral striatum and actions related to trust, such as a greater readiness to accept interpersonal risks.15 Here are some potential implications, as informed by prior research:

When serotonin levels are sufficient, individuals tend to exhibit more trusting behaviour.

Dopamine plays a crucial role in enhancing empathy, a critical element for building trust at work. When people have increased levels of dopamine, they tend to be more sensitive to the emotional states of others, leading to a better understanding of their colleagues’ perspectives and concerns. This heightened empathy can enhance trust and promote clear communication.

Trust often involves taking risks, and dopamine can influence an individual’s willingness to take such risks. Studies have shown that dopamine can reduce risk aversion and increase the willingness to trust others, even in uncertain situations. This may lead to more willingness to trust coworkers in the corporate world.

Dopamine is closely linked to the brain’s reward system, and it plays a significant role in motivating behavior. When individuals experience rewards or victories, their dopamine levels increase, reinforcing their trust in the corporate environment. This reward-based motivation is likely to enhance employee engagement, satisfaction, and loyalty, which are crucial factors for long-term corporate success.

In summary, dopamine affects trust by enhancing prosocial behavior and empathy, mitigating risk aversion, and motivating reward-based behavior.

Serotonin, Trust, and Leadership Conduct

Serotonin, which is another chemical messenger in the brain, has also been linked to various aspects of trusting behavior. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter responsible for regulating mood. Serotonin is primarily known to promote feelings of happiness and well-being, which have a direct impact on an individual’s willingness to trust others. When serotonin levels are sufficient, individuals tend to exhibit more trusting behavior, believing that others have their best interests at heart.

Serotonin also plays a crucial role in regulating sleep, appetite, and many other physiological processes in the body. It is often referred to as the “happy chemical,” because it contributes to feelings of well-being and happiness. Various studies have shown a correlation between serotonin levels and positive feelings. Research has found that individuals with higher levels of serotonin tend to experience increased positive mood states, such as happiness, contentment, and pleasure.16 Other researchers reported higher levels of positive affect and lower levels of negative affect. “Positive affect” refers to experiencing positive emotions and feelings, whereas “negative affect” refers to experiencing negative emotions and feelings.

Excessive levels of cortisol can have detrimental effects on our physical and mental well-being.

Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that medications that increase serotonin levels, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are effective in treating depression and anxiety disorders. These medications not only alleviate symptoms of these disorders but also often lead to an improved overall sense of well-being and positive mood.

So, you might ask what all this has to do with trust. Well, when leaders feel respected at work, we argue that it boosts serotonin levels by enhancing their self-confidence and sense of trust. They effectively inspire trust among their followers, which contributes to their ability to build strong connections and establish a sense of security within their teams. In short, we propose that serotonin may play a role in such leadership examples by promoting feelings of social connection, positivity, and confidence, which are essential components of fostering trust within a team.

Cortisol Levels, Trust, and Leadership Role

Cortisol, commonly referred to as the “stress hormone”, can also play a significant role in trust by affecting our body’s response to stressful situations. At the same time, excessive levels of cortisol can have detrimental effects on our physical and mental well-being. Specifically, when a leader experiences chronic stress or possesses a leadership style that induces stress in their followers, it can lead to increased cortisol levels and subsequently lower trust levels within the team. Here are some possible effects of high cortisol levels on a leader that decrease the trust level of their followers:

Impaired decision-making

Elevated cortisol levels impair cognitive functioning and decision-making abilities. Leaders experiencing chronic stress may struggle to make rational decisions.

Emotional dysregulation

When cortisol levels are high, leaders may be more prone to emotional outbursts, mood swings, or an overwhelmed state, which can create an atmosphere of unpredictability and unease within the team. Such emotional volatility erodes trust, because followers struggle to anticipate or understand their leader’s reactions.

Communication breakdown

Stress-induced cortisol release can impair effective communication. The leader may exhibit poor listening skills, be dismissive of others’ opinions, or fail to communicate their expectations clearly.

Reduced empathy and engagement

High levels of cortisol can dampen empathy and diminish the leader’s ability to connect with their followers emotionally. A leader who lacks empathy and fails to understand others’ perspectives may appear distant, self-centered, or unsupportive. This diminishes trust, as followers feel unheard, unacknowledged, or undervalued, leading to decreased engagement and commitment to the leader’s vision.

Inconsistent leadership style

Stress-induced cortisol release may also contribute to inconsistent leadership behavior. Leaders under chronic stress may oscillate between micromanagement and neglect, strictness and leniency, or indecisiveness and impulsivity. These inconsistencies erode trust, as followers are unsure about the leader’s expectations or reactions, leading to a feeling of being left in a constant state of uncertainty.

The Neurobiological Basis of Leadership and the Hormonal Characteristics of Toxic Leaders

Toxic leadership is characterized by leaders who, intentionally or not, engage in destructive, reckless, and / or incompetent behavior towards their subordinates, leading to negative outcomes for both individuals and organizations.

Leadership presence is a combination of trust, charisma, and the ability to inspire others. It involves being able to communicate effectively, make decisions with authority, and lead by example. The underlying hypothesis is that every leader can build trust.17 While effective leaders do not necessarily have specific hormonal characteristics, certain hormones can influence key traits and behaviors associated with effective leadership. It is important to note that factors such as genetics, environment, and individual characteristics also influence leadership behavior and effectiveness. Additionally, hormone levels can vary greatly among individuals.

Facts, fads, and some propositions about the neurobiology of toxic leaders

Toxic leadership is characterized by leaders who, intentionally or not, engage in destructive, reckless, and / or incompetent behavior towards their subordinates, leading to negative outcomes for both individuals and organizations.18 While it is difficult to pinpoint specific hormones associated with toxic leaders, there are certain behaviors and qualities often observed in toxic leaders. Here are some examples:

Narcissism

Toxic leaders often display an excessive sense of self-importance and seek admiration from others. They put their own interests above those of their team and may exploit or manipulate subordinates for personal gain. Research has shown that certain hormones, such as dopamine, can influence both narcissistic traits and toxic leadership behavior. Dopamine is associated with dominance, aggression, and risk-taking, which aligns with the behaviors exhibited by narcissistic and toxic leaders. However, it is important to note that not all individuals with narcissistic traits become toxic leaders, and not all toxic leaders display narcissistic traits. Other factors, such as upbringing, organizational culture, and individual experiences, can also contribute to the development of toxic leadership behaviors.

Authoritarianism

Toxic leaders tend to exhibit a dictatorial and controlling leadership style. They maintain a strict hierarchical structure and enforce compliance through fear, intimidation, or punishment. Research suggests that there can be a relationship between authoritarianism, toxic leadership, and hormonal base. These findings suggest that high cortisol levels may be associated with more authoritarian behavior, and thus provide empirical evidence to support this association.

Lack of empathy

Toxic leaders often exhibit a lack of concern for the well-being and feelings of others. They may be insensitive to their needs, dismissive of their concerns, or show no remorse for their actions. Previously, we argued that hormones, such as oxytocin and cortisol, play a crucial role in empathy and social bonding. Thus, low levels of oxytocin can be associated with non-empathetic leaders and antisocial behaviors. Similarly, increased levels of cortisol can be linked with reduced empathy and a higher likelihood of toxic leadership behaviors. This logic follows the effects of chronic stress and burnout on toxic leadership, as the biological chain disrupts hormonal balance, further impairing empathetic responses.19

How Can Leaders Embed Principles of Neuroscience to Enhance Corporate Trust?

We will close by offering eight leadership behaviors critical to fostering trust which are based on the principles of neurobiology.

- Recognize excellence: Neuroscience shows that recognition has the largest effect on trust when it occurs immediately after a goal has been met, when it comes from peers, and when it is tangible, unexpected, personal, and public. Public recognition not only uses the power of the crowd to celebrate successes, but also inspires others to aim for excellence.

- Induce “challenge stress”: When a manager assigns a team a difficult but achievable goal, the moderate stress of the task releases neurochemicals, including oxytocin and adrenocorticotropin, that intensify people’s focus and strengthen social connections.

- Provide autonomy: Once employees have been trained, allow them, whenever possible, discretion in how they do their work. In essence, show that you trust them to be able to figure things out. Autonomy is a central human need that builds trust. For example, a 2014 study by the Families and Work Institute in partnership with the Society for Human Resource Management found that 46 per cent of employees would prefer flexibility in work scheduling over a pay raise.20 And a 2015 survey conducted by FlexJobs, an online job search platform, found that 45 per cent of respondents would accept a pay cut for more flexibility in their job.21

- Enable job crafting: Job crafting is a process where employees take proactive steps to redesign their jobs. It normally involves changing tasks, relationships, and perceptions of the jobs to fit the individual’s needs, passions, strengths, and motives. When companies trust employees to choose which projects they’ll work on, people focus their energies on what they care about most. As a result, organizations like the Morning Star Company, the largest producer of tomato products in the world, have highly productive colleagues who stay with the company year after year.

- Share information broadly: According to recent research by Chris Zook of Bain and Company, only 40 per cent of employees across organizations have any idea what the goals of their company are. Forty per cent – that’s a staggering number. That means that 60 per cent of the team are wandering around, investing effort moving in directions that aren’t contributing to the company focus.22 This uncertainty about the company’s direction leads to chronic stress, which inhibits the release of oxytocin and undermines teamwork. Opening communication lines shows employees that you trust them with sensitive information.

- Intentionally build relationships: Oxytocin activation and processing developed over years of human evolution. This means that the trust and sociality that oxytocin enables are deeply embedded in our nature. Yet, at work, we often get the message that we should focus on completing tasks, not on making friends. Neuroscience experiments show that when people intentionally build social ties at work, their performance improves.

- Facilitate whole-person growth: High-trust workplaces help people develop personally as well as professionally. Numerous studies show that acquiring new work skills isn’t enough; if you’re not growing as a human being, your performance will suffer. High-trust companies adopt a growth mindset when developing talent.

- Show vulnerability: Leaders in high-trust workplaces ask for help from colleagues instead of just telling them to do things. This stimulates oxytocin production in others, increasing their trust and cooperation. Asking for help is a sign of a secure leader – one who engages everyone to reach goals.

Conclusion

Understanding the neurobiology of trust reveals the profound impact that brain mechanisms, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters have on trust-building within organizations. By exploring the roles of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, oxytocin, dopamine, and other hormones, we gain valuable insights into how trust is formed, maintained, and enhanced in the workplace. Trust is not merely an abstract concept but a tangible neurobiological process that influences decision-making, motivation, and collaboration.

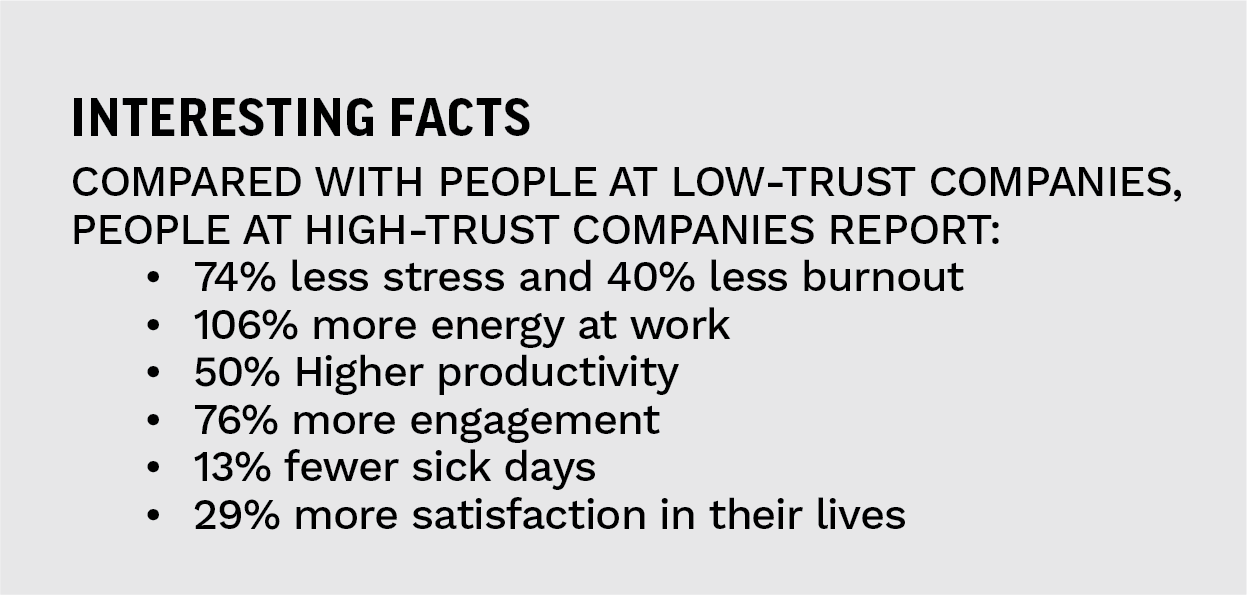

Effective leadership is pivotal in fostering trust, involving elements such as delegation, empowerment, effective communication, and consistency. Leaders who demonstrate these qualities can create an environment where employees feel psychologically safe, valued, and motivated to contribute. Additionally, organizational practices like recognition, transparency, and genuine care further solidify trust among team members.

Ultimately, a strong sense of purpose and alignment between leadership vision and team values underpins corporate trust. Leaders who inspire with clear direction, meaningful goals, and opportunities for growth can drive their teams towards shared objectives, creating a cohesive and motivated workforce. By prioritizing trust, organizations can enhance employee engagement, performance, and overall success, fostering a positive and productive corporate culture.