History has shown that when organizations have approached some threshold concerning their markets saturation, be it by product or process improvements, often a new trend emerge triggered by some form of innovation. Innovation is the key ingredient, not only for organizational survival, but for sustainability. If innovation is the key, how can businesses organise in order to foster innovation? Some businesses seem to have a natural capability to innovate continuously while others struggle to achieve minimal innovation performance.

The Imperative of Innovation

Joseph Schumpeter is usually quoted as the father of the creative destruction concept in economics, which is a concept closely associated with innovation as the engine behind business cycles and long-term sustainability, regardless of the industry under consideration. It is implicit in Schumpeter’s Theory that innovation is the major reason for business renewal.

If innovation is key for business renewal, how can businesses organise for innovation? and, unlock the benefits Schumpeter suggested. How can organizations ultimately make the capability to innovate part of their DNA?

Innovation is a broad concept that may be classified according to different reference frames. One such classification could suggest three categories of innovation: (1) disruptive innovation, sometimes referred to as radical innovation, (2) incremental or progressive innovation, which resembles a continuous improvement effort, and (3) recombination innovation, where existing concepts are combined to produce a new one.

The first innovation type, radical, happens when a certain innovation disrupts or makes obsolete an exiting concept or industry. This would be the end of the whale hunting after the petroleum industry replaced whale oil; or the replacement of horse carriages by cars. However, the car itself has not been evolving radically since his initial grandfather, hence it falls nowadays under the incremental innovation type. It has improved equipment, driving functions, luxury, but nothing really radical as such. The third category of innovation demands usually the blending of concepts, producing a new one, in a similar way that mixing water and lemon, provides a completely new product – lemonade. Similarly, all the components and subsystems one finds in a modern UCAV (Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle) already existed, however not combined as such. Airframes existed; remote controls and radio transmission of data existed; cameras existed; as well as missiles, but not combined as in such platforms. It just took someone to envision the whole recombined concept, sell the idea and make it a reality. Obviously, when talking about innovation, one may cross several domains, such as products, services or processes. To make innovation flourish within organizations and making it permanent, it helps, however, to question what are organizations and ways to approach them.

A Business Policy Model of Organizations

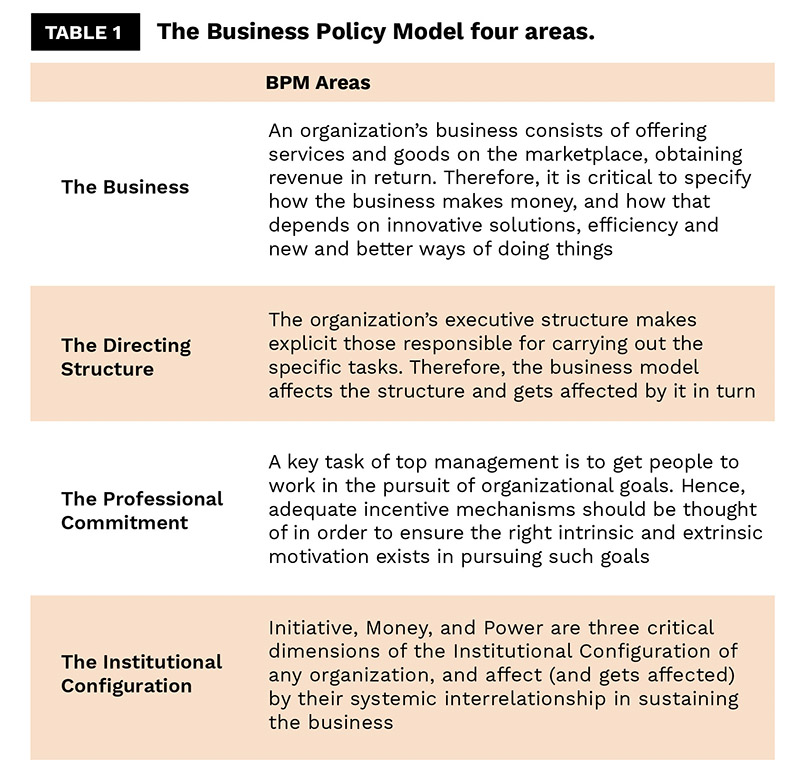

Innovation occurs within organizations. Organizations are not just systems – a group of parts that interconnect for a purpose – but political systems, with all the intricacies and human motivations that oftentimes dictate the fate of such organizations. Therefore, a Business Policy approach seems a holistic enough approach to understand such political systems. During the mid-twentieth century, Business Policy was a core and distinctive course at Harvard Business School curriculums, with reference names such as Roland Christensen, Joseph Bower and particularly Kenneth Andrews [1]. Such core course approached organizations as composed of three main governing areas: (1) the Business itself, with all its operations and production, marketing and sales, together with the support of accounting and finance, (2) the Organization, which focused on the best way to organise such human effort, and (3) the Incentive Systems, critical to keep all workforce motivated and aligned with the business strategy. By the end of the twentieth century, some authors at IESE Business School [2], further developed such Business Policy Model (BPM), by adding a fourth critical area, Institutional Configuration, which is close to what nowadays is regarded as corporate governance. The business policy approach seemed to went out of fashion during the 1980s as new lines of though at some top business schools pushed for some mechanistic models, with “X” Forces and other schematics, perhaps ignoring the nature of organizations as complex and political living systems [3]. Evidence from the last thirty years showed that business long term sustainability is not a simpler matter, and better ways shall be sought in order to promote such sustainability, which requires making innovation an endemic capability within organizations, regardless of the industry they are in. The business policy model allows in fact for a first approach to business organizations as political systems, and its four main areas are summarized in Table 1.

Having a model like this as a reference frame is helpful, however, it may not be enough to ensure innovation prospers within organizations. To unlock Schumpeter Theory’s claims within our organizations it needs understanding about which are the enablers of innovation and how do such enablers promote innovation.

Enablers of innovation

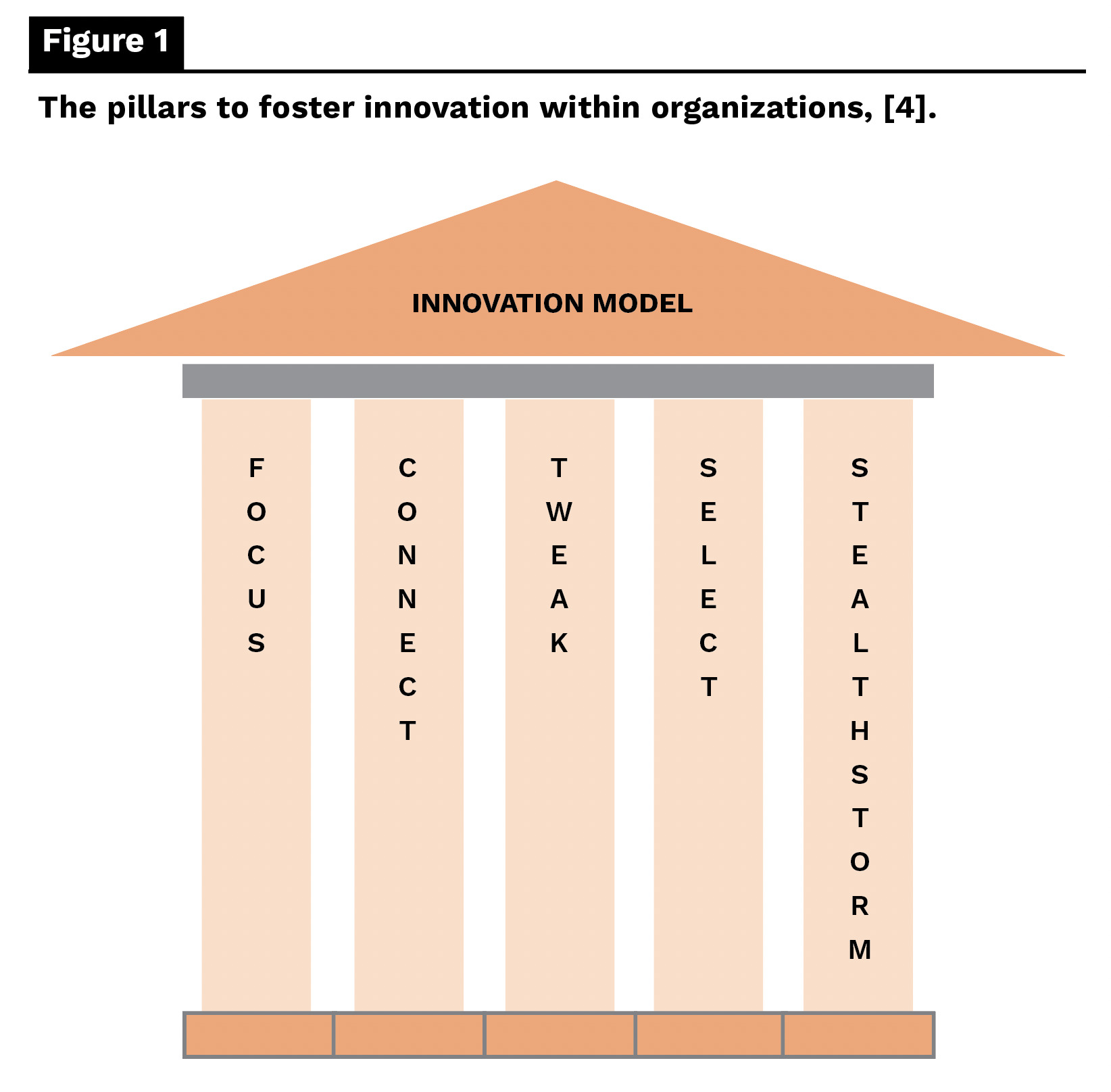

In order to control any process, one needs to understand which ‘buttons’ to push. Similarly, when developing an innovation capability within organizations the enablers of innovation shall be taken care of properly. The literature on innovation is endless, and there are some good models out there. Quite often, many such models alone are not of much help. When combined, however, with a holistic view of organizations as political systems, some achievements are possible in what innovation concerns. Some models rely on just a few critical enablers of innovation, such as [4]: (1) Focus on the ideas that are of the business interest, (2) Connect the people across the organization, so together they generate more ideas, (3) Tweak the initial ideas in order to improve them, as most good ideas come out as still poor initially, (4) Select the ideas to finance and implement, in order not to waste scarce resources with ideas of little strategic interest, and (5) Stealthstorm, which is a concept meaning that ideas are good if they can travel the political endeavour across organizations with no meaningful friction (Figure 1).

A sixth enabling factor is obviously “Persistence”, which often makes the difference between success and failure, as suggested almost a century ago by Thomas Edison, when referring to the large number of failed experiments until he finally got the light bulb functioning. Being conscious of these innovation enablers is critical, however, it is by understanding how they interrelate within the specifics of each organization that makes it possible to design better ways of organizing for innovation.

Organizing for innovation

Innovation is an imperative and change is of the essence. Such change may be triggered by understanding how the enablers of innovation interrelate each other in a systemic way. Actually, a system may be defined as a set of elements interconnected for a purpose, and Figure 2 just illustrates a possible way of interconnection among enablers of innovation.

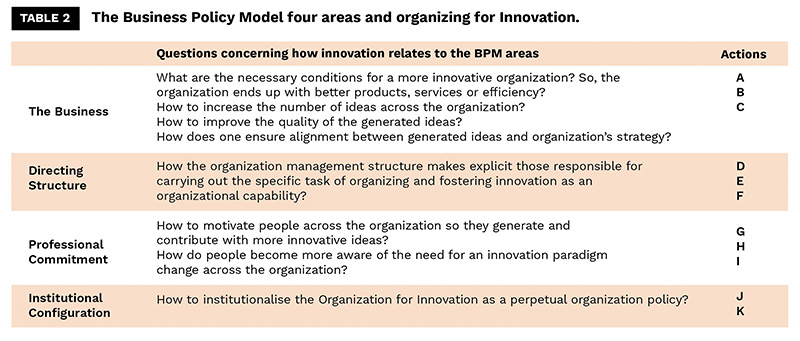

By understanding the relationships and concepts associated with each of the innovation enablers, and having an organizational framework, such as the Business Policy Model, it is possible to start putting relevant questions into perspective, specifically: (1) What to change? (2) What to change to, and (3) How to make the changes happen?

Table 2, exemplifies the sort of questions in context, which will naturally generate an associated set of actions to trigger change in achieving a more desirable future business paradigm, sometimes even triggering and evolving to an organization’s business model.

Examples of possible answers to the questions in Table 2, could be a set of actions as follows:

- Establishment of an Innovation Unit

- Ensure employees get innovation training at several levels

- Establish focus, so people don´t just generate ideas, but ideas aligned with the business strategy

- Systematically check and tweak ideas at initial stages, so the number of meaningful ideas is maximized

- Setting up a systematic idea selection system, so bad or weaker ideas are eliminated as soon as possible, saving resources.

- Establish an Innovation Incentive System, so people across the organization buy-in.

The creation of an Innovation Unit, headed by a senior manager is key, and some businesses even establish innovation committees at board of directors’ level, supporting and supervising the organizational structure for innovation, under which several programmes might be launched, from idea platforms, to idea selection or the development of innovation “champions”. The innovation incentive system is another concept critical for innovation to become systematic, as motivation is always a factor shaping people’s mindset. The creation of innovation awards and making innovation a key appraisal criterion for promotion advancement may help the organization achieve a higher systematic innovation maturity.

Summarizing

As argued long ago by Schumpeter, innovation is key for business renewal and long-term sustainability, which implies changes at several dimensions – organizational, culture, and sometimes the whole business model. Some organizations seem to get their innovation capability right, as if it were naturally part of their DNA, while others struggle to achieve minimal levels of innovation. Why does such happen? Why is it so difficult to make innovation part of an organization’s natural set of capabilities? The answers to such questions may be slightly different and dependent on the nature of each business and the industries they are in, but it is for sure found on how management understands their organizations as living systems, together with the understanding of how the enablers of innovation can be arranged together for maximum performance.

About the Author

Pedro B. Agua graduated from the Portuguese Naval Academy in Naval Sciences, specializing in Engineering. Currently a Professor of General Management at the Portuguese Naval Academy and Senior Teaching Fellow at AESE Business School, Lisbon. Professor Agua has authored many articles and book chapters featuring various systems, governance and business policy subjects. He combines his teaching profile with an extensive business background of more than 27 years in cutting edge fields as defence, telecommunications or subsea industry. Pedro holds an MBA from AESE and IESE Business School and a Ph.D. in Engineering and Management awarded by the University of Lisbon.

References

- Andrews, K. R. (1987). The Concept of Corporate Strategy. Homewood, IL: Irwin Ed.

- Vicente, A. V, & Tomás, J.L.L. (2018). Business Policy. Sevilla, España: San Telmo Ed.

- DeGeus, A. (1997). The Living Company. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Miller, P. & Wedell-Wedellsborg, T. (2014). Innovation as Usual. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.