By Nora Grasselli and Bethan Williams

How are team dynamics affected by our evermore global and virtualized business context? An innovative game created at ESMT Berlin pits business leaders against fictional hackers to find out.

“The Virus”

Berlin, January 2020. A group of executives is ushered silently into a conference room. With little in the way of preamble, a grim announcement is made: their company is under cyber-attack. Anonymous hackers have sent a series of cryptic demands which must be carried out within the next 30 minutes – or else the company’s entire client data will be made public.

And that’s not all. Like many in its field, the firm has recently looked to expand its international client base and is now operating across three different locations. The hackers have sent fragments of their demands to each office, meaning each local team has only part of the information required to untangle and crack the series of coded messages.

A deathly hush falls upon the room as this news sinks in. But exactly what kind of action may come as a surprise. Paper, scissors, iPads, and felt-tip pens are quickly distributed. A countdown clock is projected onto the conference room wall.

This is, of course, a fabricated crisis scenario for teaching purposes rather than a real existential threat to the company – one that forms the introduction to an executive education exercise created by ESMT’s Dr. Nora Grasselli, a leading expert in organizational psychodynamics. The exercise, dubbed “The Virus,” aims to facilitate discussion and learning around the topics of leadership and teamwork in the modern age.

Though it may be a game this time, the threat of a virus infiltrating and infecting valuable business assets is one that feels all too real to today’s business leaders. Whether it’s an invisible biological enemy (say, a coronavirus pandemic) paralyzing all normal business activities, or an anonymous group of hackers threatening to access confidential data – such unforeseen crisis situations demand impeccable teamwork if the company has any chance of surviving intact.

Challenge: Global, virtual, and liquid teams

But what does impeccable teamwork mean in practice? To understand this is to appreciate the seismic changes that team constellations and teamwork have undergone in the past decade.

Global teams

In bygone years, it would be a matter-of-course that everyone assigned to a project would commute into the same office, from Monday to Friday. Progress updates and feedback happened primarily in face-to-face meetings – either formally at weekly meetings or informally in the staff canteen over lunch.

Since the turn of the century, however, it has become far more likely that several of the crucial elements of a team’s project will be planned, debated, and carried out in offices on the other side of the world. A bevy of online video conferencing and project manangement tools such as Slack and Asana were in widespread use even before this year’s coronavirus pandemic to cater to these global teams. These tools provide simulated spaces where team members in different locations can meet and work together in real time – from London, New York, and Shanghai – as easily as if they were in the same office.

“Going global” has an obvious appeal for many business leaders looking to gain a competitive advantage. As the head of sales for a growing online retailer, you may want to distribute your customer service representatives across time zones to better look after clients living in new markets. As the lead product designer at a tech start-up, you may find that a freelance web developer based in New Delhi can fix the back-end code in your new app for a much cheaper price than the market rate in your own city.

The benefits brought about by hiring globally are not only seen on the balance sheet either. Research has shown that global teams score highly in measures of creativity and knowledge generation. With improved access to a range of experts, these teams can expedite the exploration of innovative solutions and demonstrate increased productivity (Batarseh et al., 2017).

However, it is no secret that working together without face-to-face interaction has its pitfalls. It is all too easy to send out a Zoom invitation to your team but neglect to specify the agenda or the roles of meeting invitees. In a group video call, this lack of a formal framework is especially risky and can exacerbate feelings of disengagement among participants. Others on the call are both physically distant from the colleague arguing her case and more vulnerable to becoming mentally distant too. After all, they are dealing with the added distraction of their email inbox or internet browser being just a click away.

The reaction of managers to such disengagement should not be to increase top-down surveillance of their remote team members. Micromanagement is an easy trap to fall into – functioning only to devalue the expertise of the individual team members, inhibit the creative exchange of ideas, and ultimately dismantle trust. There are several much more effective strategies that global managers can use to capitalize on the greater range of expertise and flexibility afforded by a global team.

Research has confirmed that global teams can be double-edged swords. On the one hand, they generate a wider range of creative ideas, often bolstered by the diversity of cultures and backgrounds represented on the team. On the other hand, their ideas are often less coherent and they poorly manage conflicts that arise along the way (Batarseh et al., 2017).

Virtual teams

The second career trend is the move towards virtual teams – we are spending more time collaborating with each other online, regardless of our physical distance from fellow team members. The more “virtual” our team becomes, the more likely it is that clients from around the world will benefit from our work. However, a higher degree of “virtuality” also translates to a higher probability that we will not overcome the challenges faced by today’s global teams.

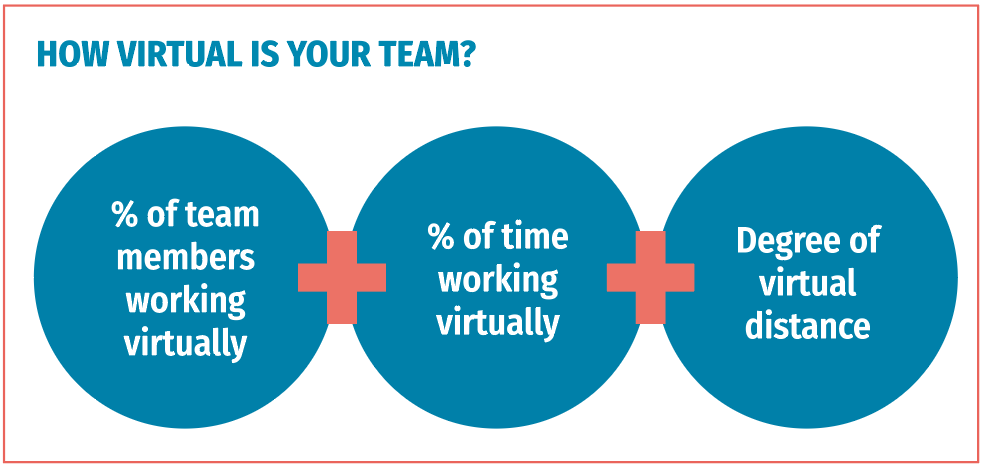

The degree of virtuality in any project team can be roughly estimated by adding the percentage of the team members who work virtually, the percentage of time the team is working in a purely virtual set-up, and the degree of so-called virtual distance.

The degree of virtual distance is composed of six elements:

- Spatial dispersion: the total distance between team members

- Cultural dispersion: the number of team members with differing cultural backgrounds

- Social dispersion: the distinctiveness of team members’ professional and social networks

- Temporal dispersion: the number of time zones covered by the virtual work

- Organizational dispersion: the total variance of organizational units and hierarchical levels involved

- Digital dispersion: familiarity and know-how regarding the use of digital technologies (Schweitzer and Duxbury, 2010)

Liquid teams

The third major shift in team dynamics in recent years has been towards liquid teams – those in which individuals are constantly being swapped in and out. While the replacement of team members can also happen when we are collaborating face-to-face, we are seeing much more liquidity in virtual teams these days thanks to the lower group boundaries fostered by digital communication technologies.

It is no exaggeration to say that this phenomenon can be an absolute disaster for team development. A team member taken out mid-project will often prove to have been critical to its success, not only due to their project-relevant knowledge and expertise but also due to the unofficial role they had played within the team. This role may not always be immediately apparent to the management who arrange the redistribution of staff – in many cases the decision makers at HQ are left dumbfounded when the project then falters or stalls.

Solution: A game to replicate the modern team environment

Here in the executive education department at ESMT, we place great emphasis on pioneering our own teaching methods for the executive classroom. “The Virus” is a digital tool we use to explore managerial response to the challenges faced by modern-day teams.

The concept originated in visits with our executive clients to commercial escape rooms in Berlin, where teams of players worked together against the clock to discover clues, solve puzzles, and “escape” a fictional scenario – perhaps a mock prison cell or a haunted house. For ESMT Berlin’s open-enrollment program Leadership in Action, Dr. Nora Grasselli began periodically swapping team members between rooms without forewarning, as a way of replicating the liquidity of modern teams. A team of executive coaches were also hired to observe each room and facilitate a reflective debriefing session.

The talking points that came up in the debriefing sessions were promising. Participants came out of the escape rooms energized and keen to discuss how they had come together as a team where they had rallied together, and where they had gone wrong. Moreover, participants reported that their most frustrating moments felt in many ways familiar. The communication breakdowns they had experienced in their workplace were played out in miniature during those intense minutes in the escape room – often directly after a team member had been swapped with someone from a room down the corridor.

Together with colleague Hannes Gurzki, an expert in branding and strategy at ESMT, and Fabian Hemmert, a professor in interface and UX design, Grasselli began designing a game using a mobile app that simulates a typical escape room scenario. The team’s vision was to create an entirely immersive app-based experience that would produce maximum learning potential with minimum set-up. A few iPads, some basic stationery, and a reliable Wi-Fi connection would be the only preparation required. Delegates taking part in executive development programs on the ESMT campus would no longer have to travel to external venues, and corporate clients could experience the session from their own offices.

“The Virus” has now been played by over 150 executive education participants since the summer of 2019. Unlike a physical escape room, this virtual escape game replicates the global and virtual dimensions of modern teams. Rather than literally putting their heads together to solve the devious riddles, players are separated into smaller groups and placed in different rooms (when on campus) or connected virtually via conferencing software (when played remotely). The ESMT facilitators and executive participants may therefore be located anywhere in the world.

Session takeaway: Please do try this at home

During this year’s coronavirus crisis, many managers found themselves leading projects from their home office for the first time. So what makes a team in this very modern context successful? When asked, most people assume that so-called socio-emotional processes must be a decisive factor. Thus, team leads try to create more opportunities for small talk in virtual meetings or plan more informal interactions, such as virtual happy hours, so that colleagues get to know each other beyond their professional personas. Such measures do have their merits in certain contexts, but time and time again we see that teams can work very well together without ever meeting up for a beer, virtual or otherwise.

The role of leadership

Much of what the ESMT faculty teaches in leadership programs can be summed up with one golden rule: different project types require different leadership approaches. It is especially important to comprehend this when your team has global, virtual, or liquid elements.

As such, Grasselli highlighted “leading in a virtual context” as a key learning objective for the executive escape game, and made sure that the importance of a flexible mindset would become clear to anyone who played the game. The series of tasks that teams must complete to “beat the hackers” are diverse, and the cryptic instructions that appear periodically as they progress leave much open to interpretation. This is not an exercise where the intended learnings are handed to program participants on a plate.

Without the formal protocols, hierarchies, and personal alliances that exist in a real-world organization, the three groups of players are free to establish their own framework for communication and task distribution. As they tackle the first task, stronger voices tend to take control over the audio stream and others tend to fall into line. The organizational blueprint that emerges within this task will generally remain the norm throughout the thirty-minute game. Roles and responsibilities only occasionally shift and evolve as the players proceed.

More often than not, the groups of players we observe do not take time to discuss the organizational structures they are using to process and share information. This is very much typical of a team collaborating only virtually – forced group cohesions and the “live effect” of a conference call tend to be prohibitive to these sorts of discussions, which may be seen by some in the group as a waste of time. The minority of teams that take the time to discuss their roles and adjust them throughout the game reap the benefits – and in our experience, complete the game in a much shorter time frame.

This is very much an intentional outcome of the game’s design. To complete one task, for example, it is demonstrably more efficient for the unique information that the teams have in front of them to be collected in one place. Without one of the groups collating this data and analyzing it holistically, it is far more difficult to solve the riddle. In this way it represents a typical “HQ task,” one that requires a bird’s-eye view of the situation to extract meaning.

In the subsequent task, however, the information that the app distributes to each group requires some “local context,” that is, information from the physical environment around them. This task is therefore much quicker to solve when the three physically distanced groups work simultaneously on their own pieces of the riddle in their separate “local offices”.

With the sound of a countdown clock ticking away in the background, the players must be able to quickly identify and implement the most efficient approach for each task.

The need to desynchronize

Teams working across time zones with different national holiday patterns cannot (and should not) follow a project plan in a strictly synchronized and linear fashion. To do so is to waste time, and deadlines are likely to be missed if management insists on constant synchronization. Instead, space must be made for periods of desynchronization, in which some parts of the team are trusted to take a step back from the collaborative space to work independently on their own contribution, while other team members prepare for upcoming tasks. Properly managing that process of desynchronization and resynchronization is vital to the efficiency of modern teams.

Even within the half hour that players are “under cyberattack” in this game, they can experience the benefits of desynchronizing some workflows. One task involves deciphering the meaning of an enigmatic sentence – which turns out to be different for each of the three physically-distanced groups. If the players default to analyzing each one all together, or realize too late that they have all been sent different sentences by the fictional hackers, they are likely to waste valuable time.

“We are one team, we have to stick together” is a long-standing myth that causes teams in both physical and virtual settings to create distraction. A typical example is a progress meeting in which each team member must detail in turn how they did their part of the job – even aspects irrelevant to the other team members. When playing “The Virus,” many have fallen back into these habits. As one executive put it during the debrief session: “I was scared that something would go wrong if we didn’t make sure we were constantly in touch”.

There is anecdotal evidence that this is a generational issue. During gameplay we have observed younger and less senior team members automatically put the call on mute while their group discusses the clues in front of them locally – a sensible step, in many cases, as it means their discussions will not distract those in the other rooms. By contrast, senior executives with 30 years’ experience under their belt are more likely to freak out when they see another group has muted itself. They want to be kept fully informed of all developments to feel in control.

But due to the pace of this game, communicating all information to everyone just isn’t efficient. The most successful teams are those that manage to agree together on a process that allows all three teams to work simultaneously within their own context at least some of the time.

Processes, processes, processes

Virtual teams must create crystal clear structures and organizational processes around their project so that everyone knows where they stand. When there are outward pressures on time and resources – as is often the case in these fast-paced teams – explicitly setting down guidelines falls by the wayside. Taking time to decide on these macro-processes at the start of a new virtual collaboration is often not prioritized or even forgotten about entirely.

When team leads are working face-to-face with their team, such organizational processes are more likely to be implicitly communicated, with non-verbal ways to monitor and manage team behavior. In an office environment you can easily pop over to someone’s desk to share knowledge, check capacities, and monitor project progress in a non-intrusive way. We may even know when our colleague is going on their summer holidays after seeing their wall calendar or chatting in the canteen – granting us a more accurate overview of upcoming delays in the project pipeline.

In a virtual scenario, we too often lose these insights and find ourselves unaware of what others are currently working on, and how they see their role within the team. Too little care is taken on managing the flow of information and redistributing tasks between team members to reflect capacities. Regular task-related discussions – What? Why? How? Who? – are therefore key to virtual team success.

Without making room in our virtual collaboration space for such discussions, we may not notice the problems right under our nose. In one memorable session playing “The Virus” on the ESMT campus, two of the groups unilaterally decided they would be in charge of gathering all data and solving all tasks. These groups channeled all the solutions to the third group, who were responsible only for punching the numbers into the iPad. The two eminently experienced managers in this third group spoke up only in the debrief – they said they had found the entire experience dreadful. They didn’t know why they were receiving these nonsensical strings of numbers and, in the end, felt that they hadn’t contributed at all to the team’s success. This really brought it home to the group as a whole that you need to look after your distributed team members.

Do not treat virtual communication with remote offices as a one-way relationship with no autonomy and no opportunity for feedback. As a manager of global offices, you have a clear choice – do you dictate top-down solutions or do you allow these units to become part of the solution? Your answer will have a huge impact on your global team’s morale.

Winning formula: Encouraging play in the executive classroom

Dr. Nora Grasselli has always been an advocate of experiential learning in the executive classroom. “The days of long, dry business case studies are over,” she is fond of saying, and counts gamification as one of the most effective tools in her teaching toolbox. Rather than passively reading about another company’s specific dilemma, session participants experiment and play within the safe space of a fictionalized scenario. Theories are no longer abstract – players are thrown straight in to the unpredictability that comes with working in a team made up of real human beings.

Grasselli was influenced in her attitude to teaching by the British psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott, who studied the role of play in early childhood developmental processes. Winnicott put forward the concept of “potential space,” within which everything that exists in the real world can be reinvented to create something new (Winnicott, 1971). “The great benefits of play (…) are the ability to become smarter, to learn more about the world than genes alone could even teach, to adapt to a changing world” (Brown and Vaughn, 2009).

Play itself is not seen as part of our ordinary adult lives, much less our professional lives. When we are given the license to play, we can approach the experience with less seriousness and fewer preconceptions. We become more open to experimenting with the unknown, breaking down, or bending rules, and making space for potential failure. These tendencies just happen to be vital ingredients for innovation (Ludens, 2016).

Gameplay in “The Virus” is intentionally based around a hyperbolic scenario rather than a sober real-life business case. The story-led interface of the app builds up a sinister characterization of the unseen hackers, quickly uniting the group of executives against their common enemy. The adrenaline is then ramped up even further by playing tension music at choice intervals. Indeed, it would be clear to an outside observer watching any given session that the executives really do want to “beat the hackers.” The stakes feel high, even if on a rational level everyone is well aware that it is just a game.

Tension certainly builds as the countdown clock ticks – but ultimately, the gameplay is designed to be more of an all-out sprint than a slow-burn marathon, and time is up after just 30 minutes. What participants go through in that short time frame often wakes in them half-forgotten memories of similar dynamics they experienced on their own projects at work. The micro-situations that the players are put into during the game really resonate, and discussions during the game debrief quickly turn to their teams in the real world.

Talking to ESMT clients who have already taken part in Grasselli’s session, it becomes clear that the sense of fun and adrenaline they experienced during gameplay also heightens their memory of what they learned. “Learning to communicate with your team well in that situation is not easy, but it showed us how it feels in reality,” reported Joana Alexandrescu to the Financial Times, “it was better than just learning theory.” (Moules, 2019).

For many leaders of corporate teams, work-from-home mandates brought about by the coronavirus crisis meant suddenly conducting brainstorming workshops, team progress updates, and feedback sessions in virtual spaces for the very first time. Many of the habits developed in this brave new world will seep into the team’s everyday working life even after most of the measures are lifted. For us here in the executive education department at ESMT, helping our clients experience first-hand the help and harm of these habits is vital.

About the Authors

Nora Grasselli has been a program director at ESMT Berlin since 2012 and is responsible for the design and delivery of its flagship programs as well as customized programs for executive clients. Prior to joining ESMT, she worked as a strategy consultant for the Boston Consulting Group and was a lecturer for MBA and executive programs at multiple business schools including HEC, Oxford Said, Reims School of Management, and the Central European University. Grasselli earned her doctorate in management and organizational behavior at HEC School of Management and is certified in executive and organizational coaching by the Columbia Coaching Certification Program of Columbia University.

Nora Grasselli has been a program director at ESMT Berlin since 2012 and is responsible for the design and delivery of its flagship programs as well as customized programs for executive clients. Prior to joining ESMT, she worked as a strategy consultant for the Boston Consulting Group and was a lecturer for MBA and executive programs at multiple business schools including HEC, Oxford Said, Reims School of Management, and the Central European University. Grasselli earned her doctorate in management and organizational behavior at HEC School of Management and is certified in executive and organizational coaching by the Columbia Coaching Certification Program of Columbia University.

Bethan Williams joined ESMT Berlin as a program manager in 2019. She holds a master’s degree in modern and medieval languages from the University of Cambridge and completed a post-graduate scholarship in Mandarin Chinese at the Shandong University of Science and Technology. Prior to joining ESMT, Williams worked as a translator for Allianz Deutschland and as a sales manager for a chain of schools in China. Her professional career in the global education market includes digitizing programs for executive education clients, content writing, and research assistance, especially in areas related to Sino-European business and intercultural management.

Bethan Williams joined ESMT Berlin as a program manager in 2019. She holds a master’s degree in modern and medieval languages from the University of Cambridge and completed a post-graduate scholarship in Mandarin Chinese at the Shandong University of Science and Technology. Prior to joining ESMT, Williams worked as a translator for Allianz Deutschland and as a sales manager for a chain of schools in China. Her professional career in the global education market includes digitizing programs for executive education clients, content writing, and research assistance, especially in areas related to Sino-European business and intercultural management.

References

Batarseh, F.S., Usher, J.M. and Daspit, J.J. 2017. Collaboration capability in virtual teams: Examining the influence on diversity and innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 21(04), p.1750034.

Brown, S.L. and Vaughan, C.C. 2010. Play: how it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. New York: Avery, p.49.

Huizinga, J. 2016. Homo Ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Kettering, Ohio] Angelico Press.

Moules, J. 2019. “Business schools embrace games as learning tool.” Financial Times, December 2, 2019.

Winnicott, D.W. 1971. Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock.