By Simona Rocchi, Bahaa Eddine Sarroukh, Karthik Subbaraman, Luc de Clerck and Reon Brand

How do brands stay meaningful and relevant in the 21st century? One powerful route is to deliver high value to customers while addressing wider social and environmental issues as an integral way of doing business. But doing this requires rethinking how value is created. In this article, we explore case studies of leading companies who are putting this new value creation and sharing into practice. From these we draw seven recommendations for enterprises wanting to follow this transformative economic path.

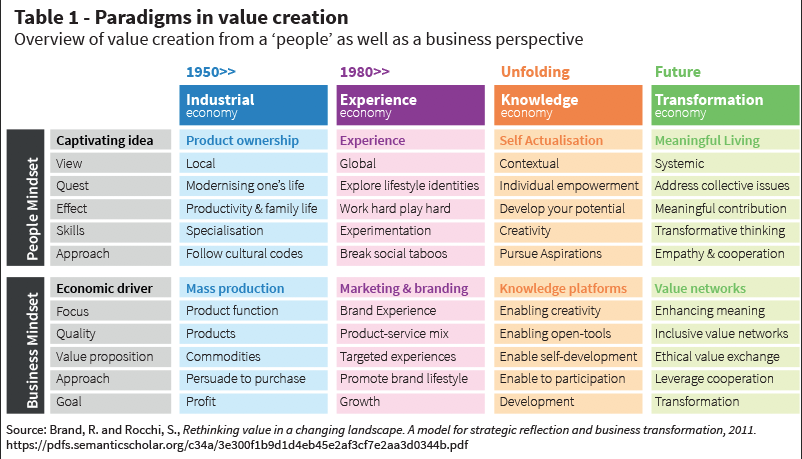

To understand how to go forward, it’s useful to briefly look back at how the transformative path has emerged as the latest wave of value creation. The initial wave arose during the Industrial Revolution when large numbers of newly-urbanised people first had access to mass-produced goods that improved their lives. In the 1980s, this form of value creation came under pressure in advanced economies as businesses faced relentless competition, market saturation, changing labor conditions and stricter regulation.

With products becoming commodities, leading companies began developing experiences as a way to compete, setting the scene for aspirational brands such as Armani, Louis Vuitton, Camel and Apple. In the 1990s and the 2000s, the Internet and digital information and communication technologies triggered a third wave, where value creation became democratised with almost anyone able to generate value. Digital platforms such as eBay, KickStarter and Shapeways 3D Printing supported self-empowerment, e-business and peer-to-peer opportunities.

Today, these various economic paradigms coexist in advanced and emerging markets, progressing at different speeds and scale. And a fourth wave is starting to appear: the “Transformation Economy”. This is driven by the realisation that despite economic progress, the world’s population is facing persistent socio-economic inequality (especially in emerging markets) and mounting environmental challenges. People are looking for solutions to global issues that affect their quality of life, and this is opening new business spaces. (See Table 1)

Recognising this shift, certain brands are directing some of their value creation efforts in new directions, in particular towards the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).1 The quest for answers and opportunities in societal goals and collective needs is influencing research, development and design in companies as diverse as Danone, DSM, Interface, Johnson & Johnson, Tesla, Unilever, Vodafone, and Royal Philips, to name a few. This is not philanthropy or Corporate Social Responsibility. These companies are following a commercial rationale to re-direct part of their investments in innovation towards new meaningful solutions that can drive business development.

The size of the challenge – and the opportunity – is huge. According to one estimate by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the SDGs could cost between USD 2.5 and 4.5 trillion a year2 between 2015 and 2030. However, complex global issues cannot be solved by any single company or stakeholder. In this new paradigm, business value is associated with inclusive value networks that can develop context-specific solutions. The way ahead lies in a variety of venturing and cooperation models that share complementary capabilities, resources, investment risks and return on investments – networks which together can amplify positive social, economic and environmental impact.

Such networks may include Private-Public-Partnerships (PPPs), as well as a variety of For-Profit and Not-for-Profit cooperation platforms. But these PPPs differ from their traditional task-oriented, transactional “contract-out” counterparts in which private companies are seen as vendors used to save costs rather than as partners in helping to maximise outcomes. The new PPPs are collaborative, value-sharing ecosystems of governments, large companies, start-ups, NGOs, and international and academic institutions. They mobilise multiple stakeholders around a common goal and specific targets: for instance, reduction of maternal mortality or CO2 emissions by a given percentage, instead of conventional PPP activities such as building air purification systems or new hospitals.

This evolution has been documented by authors such as W. D. Eggers and P. Macmillan in their book The Solution Revolution,3 and in publications such as the World Economic Forum’s 2016 paper, Health System Leapfrogging in Emerging Economies.4 Often initiated by visionary leaders or motivated core cross-sector teams, value networks target long-term financial sustainability incorporating innovative financing, efficient cost structures and new sources of revenue. And they are able to adapt over time to ensure the fulfillment of the pre-defined goal.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Pioneers of the Transformation Economy

Although the necessary business models for this new paradigm are not yet mature, case studies from the early pioneers offer insights into how to proceed. They illustrate how mobilisation of people and value-sharing approaches generate solutions that create better living conditions, support social equity, and respect the environment, as well as delivering economic returns on investments.

One of the first ground-breakers was Interface®, a manufacturer of modular carpet. In the 1990s, CEO, Ray C. Anderson,5 was inspired by concepts of the “restorative economy” and “waste as value, not cost”. He challenged the company to set bold corporate environmental goals and to pioneer closed loop systems with targets such as “zero waste” and “zero impact by 2020”.6

Now a perfect fit with SDG 12 (Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns), Anderson’s ambitions were almost unheard of at the time. Interface had to seek partners to develop the required knowledge, capabilities, and competencies in cleaner production techniques, renewable energy and waste recovery. It also had to set up a network of stakeholders able to provide infrastructure and take-back and recycling channels. As a result, Interface moved away from the traditional industrial economic paradigm of selling carpets based on ‘taking-making-wasting’ to become a provider of ‘indoor comfort’, offering customers superior value through recyclable and upcyclable leasing solutions. It turned the issues of sustainability and the cost of waste7 into a billion dollar corporation, dispelling the myth that focusing on environmental challenges negatively affects the bottom line.

For another early pioneer, Grameen Danone8 Ltd, the impetus came from two founders who focused a big vision onto a well-defined achievable goal. One was Franck Riboud, at the time CEO of Danone, a French multinational fresh dairy products company committed to “bring health through food to as many people as possible”.9 The other was Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank and acclaimed worldwide for establishing micro-credit in developing markets. Together Riboud and Yunus aimed to bring low-cost, fortified yoghurt to malnourished children across Bangladesh.10,11 One cup of the “Shokti Doi” yoghurt would cover a child’s daily requirements of vitamins, salts, calcium and proteins.12

From current perspectives, the business is aligned with SDG 1 (End poverty in all its forms everywhere) and SDG 2 (End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture), and from the start it produced positive impacts across the value network.13 The milk was purchased from local micro-farmers, and its micro entrepreneurs, the “Grameen Danone Ladies”, delivered yoghurt to rural areas via door-to-door distribution receiving a 10% commission for their services. In total, Grameen Danone Foods created about 1,600 jobs within a 30 km radius around its environmentally friendly factory in the Bogra district.14

More Recent Examples

Another pioneer is the Socimex Group, led by Ibrahim Issaoui. Since its founding, Socimex Group has worked to bring prosperity to the people of the Democratic Republic of Congo. According to Mr. Ibrahim Issaoui, reforming the education system to produce more skilled workers out of school is among the company’s key objectives in the coming years.

Other companies are now following in the footsteps of these pioneers including world leaders such as Unilever. In 2014, Unilever coordinated the creation of a Post-2015 Business Manifesto15 endorsed by over 20 leading companies, setting out a vision for the role of business in achieving the SDGs. Unilever itself is engaging with the SDGs through the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan16 and its transformational change agenda. This agenda defines three areas where the company believes it has ‘the scale, influence and resources to make a big difference’: eliminating deforestation; making sustainable agriculture mainstream; and “working towards universal access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene”. In this third area, Unilever sees the largest opportunity to both deliver on SDG 6 (Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all) and to add value for its own business.

Unilever uses advocacy on public policy and partnerships with governments, NGOs and other industry players to achieve this goal. The company has helped establish the WASH4Work17 coalition, part of the UN-Business Action hub, and is a member of the Toilet Board Coalition which seeks to develop sustainable and scalable commercial solutions to the sanitation crisis. It is also measuring the impact on the communities these initiatives seek to transform. For instance, Unilever’s Lifebouy hand soap18 brand has conducted a clinical trial19 of its handwashing behaviour change approach.20 Involving 2000 families in Mumbai, India, the trial demonstrated that children in the intervention group had 25% fewer incidences of diarrhoea, 15% fewer cases of acute respiratory infections, and 46% fewer eye infections than the control group.

The transformative path is not always smooth. For example, Grameen Danone struggled due to an incomplete understanding of its target consumers’ tastes and preferences, their purchasing power and the local financial and infrastructural resources.21,22 But for many initiatives the biggest challenge is trying to scale beyond an initial setting.

Nonetheless there are success stories – such as that of Vodafone, Safaricom and M-Pesa. Today, M-Pesa is a mobile phone-based money transfer, financing and micro-financing service that reaches 25 million23 people in Africa, Asia and Europe. Yet, it began as a pilot project looking at ways to reach “unbanked communities”.24 Telecoms company, Vodafone and its Kenyan affiliate, Safaricom, had an idea for the disbursement and repayment of micro-finance loans via mobile phones. However, the pilot revealed that people really wanted a service which would allow city dwellers to send home money to relatives in distant locations via phone messages.

Despite doubts about its viability and financial regulatory issues, the service launched in 2007 when Kenya’s Central Bank gave permission on an experimental basis. By meeting its users’ needs and expectations, M-Pesa has since enabled millions of people on low incomes to access basic financial services, and the business has scaled successfully to Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mozambique, Lesotho, India, Romania and Albania. It has also spurred Safaricom to integrate the SDGs (particularly 9, 8, and 10) within its corporate strategy.25

An On-going Example – How Philips Supports Healthcare Transformation in Africa

Philips is committed to delivering innovation able to improve the lives of 3 billion people each year by 2025. It also believes that the UN SDGs 3 and 12 are critical to bettering the health and sustainability of the planet and its people. This led Philips to identify a clear issue for its transformative innovation efforts – strengthening healthcare at primary level in low-resource settings in Africa and South East Asia (aligned with SDG 3, Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being at all ages). And in September 2017, the company extended its commitment to primary and community care by announcing its aim to improve the lives of an additional 300 million of people a year by 2025 in underserved communities.26

Such initiatives matter. Seventy percent of Africa’s population still lives in rural areas, frequently without access to even basic health care. Facilities that do exist often lack clean water and electricity, and maintenance is poor. There are shortages of healthcare workers, and few effective referral systems to secondary and tertiary care. Governments struggle to sustain public healthcare systems financially, while people risk falling into poverty due to the cost of care.

Against this backdrop, Philips has recently entered into an SDG Partnership Platform27 with the Government of Kenya and the United Nations to accelerate access to primary healthcare. More widely, Philips aims to address some of the most urgent needs: family planning and antenatal care, newborn and infant health, basic emergency care, mental resilience and health education on communicable and non-communicable diseases (such as cervical and breast cancer and diabetes). However, experience shows that single-issue projects often fail. What’s needed is a holistic approach that recognises the inter-related effects of the many challenges confronting primary care – an insight that became one of the starting points for Philips and its Community Life Centers (CLC).28

The Community Life Center Platform Ecosystem

A CLC29 expands a primary care facility – typically focussed on mother and child care – into a community hub, supported by infrastructure and services beyond healthcare alone. In collaboration with business and local organisations, the center may sell drinking water, electricity, solar lighting products and access to the Internet. This improves quality of life for the whole community, creating opportunities for small business development, sporting and social activities, as well as enabling the health facility to generate income to fund itself. Moreover, the CLC approach is modular so it can adjust to the size of population being served, and adapt as lessons are learnt and additional needs identified.

Initial Projects in Kenya and Further Implementation

Philips established the first two CLCs in Kenya. In June 2014,30,31 a CLC opened in Githurai, (a semi-urban area in the east of Nairobi) with the goal of reducing the extremely high rate of maternal and newborn mortality in the local community. The second,32,33 is in Mandera,34 a rural county in north-eastern Kenya with one of the world’s highest maternal mortality ratios.35

For these projects, Philips worked closely with the Ministry of Health, local governments, other businesses and NGOs. The CLCs were scoped in collaboration with all the stakeholders including the local community; the design and research team leveraged “design thinking” and “people centric” capabilities and tools to gather qualitative, context-specific, socio-cultural insights. Philips also drew on other core capabilities – clinical consultancy, health systems expertise (particularly in public health and evaluation), and new business development – to provide the medical hardware and services, work- and patient-flows, and training. This training includes also introducing Community Health Workers (CHWs) to a social franchising model where CHWs offer care in people’s home supported by the Philips medical backpack.

More recently, in 2017, the implementation of a mini-CLC in a remote rural site in Tadu,36 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, marked an important step in confirming the capacity of the CLC approach to transpose and scale to different geographical and socio-cultural settings. Elsewhere, Philips is part of a consortium led by Amref to establish a CLC focused on the delivery of sexual reproductive health services in Ethiopia. The company is also investigating new opportunities to set up CLCs in Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia.

Measuring and Learning

Measurement reveals the CLCs’ outcomes. For example, in Githurai a locally-approved operational monitoring and evaluation plan confirmed its positive results. Recent data indicates that some 6000 clients were seen in outpatient visits in the first quarter of 2017 with adult women comprising 63% of the female population (a six-fold increase since the CLC was opened). And ante-natal visits (new and repeat) have risen from 6 to 13 per quarter, to as many as 670 clients.37 Furthermore, as patient and visitor numbers have grown, services such as street food vendors, public transport and private “boda boda” motorcycle taxi services have flourished.

More widely, Philips and its strategic stakeholders are engaged in studies and evaluations to explore cost implications, quantification of clinical performance, financial models and use-cases for long-term sustainability of CLCs. Lessons have been learnt about regulatory issues (e.g. over a healthcare facility wanting to sell water to finance day-to-day operations in a context where health care is often free); and about the importance of initial scoping, clearly defined joint goals and roles and responsibilities.

Internally, Philips has crystallised this learning into a “cookbook”, detailing the methodology and processes that constitute the CLC approach. Although each situation is different and requires complex solutions based on high-level consultancy and cooperation, this cookbook will facilitate future scaling by enabling next iterations to draw on what has gone before.

Seven Recommendations for Innovating in the Transformation Economy

What do these case studies reveal about using innovation to turn societal challenges into opportunities for value creation? We believe the examples in this article share seven factors that can help innovators, entrepreneurs and corporations who team up across sectors to create sustainable business for the long-term.

1. Select a “burning” issue, take ownership and mobilise stakeholders

Selecting the right issue is fundamental. Is this a significant issue where our company’s capabilities can clearly contribute towards creation of a solution? Is the issue in line with our overall strategic direction and brand promise? If the answer to both questions is yes, it will be easier to mobilise internal support and to ensure that the company is in a credible position to take action.

Maximising the chances of success also depends on identifying an issue of the right size, which can be translated into an initiative with the potential to scale. This avoids daunting complexity and makes it easier to demonstrate progress, in turn inspiring confidence in stakeholders and partners. Initiators also need a strong narrative to motivate employees and to encourage external partners to join forces.

2. Identify the enablers for success

Next, take stock of the enablers for success such as funding, policy and legislation, R&D, technology, logistics and operational capabilities, and the level of interest from stakeholder groups. This helps identify where the company can contribute most effectively, and where it needs to rely on partners or other stakeholders and to reach out to them with the right call to action.

3. Team up with the right partners

Addressing complex issues requires partners that are in for the long haul, who are willing to learn together and help each other. In the scoping period, the parties need to develop trust, align their thinking on using their capabilities, and agree on a governance structure that ensures results over time. As well as sharing the risks, responsibilities and benefits, partners also need to combine complementary expertise, global know-how and local contextual insights. Experimentation, co-venturing and new business models will often be necessary; as will knowledge experts; deep local contextual insights from for-profit and non-profit stakeholders; and leveraging trusted social networks. In the Transformation Economy, the “how” to act and the “with whom” are typically as important as the “what”.

4. Create a common definition of value among stakeholders

Cooperation and commitment from a range of stakeholders and partners requires transparency and trust. Parties should be able to discuss and agree on the notion of value in the context of their joint-action and how value will be created and shared. Business modeling should reflect this and state expectations as clearly as possible. Mechanisms for the regular review of value flow and for maintaining a high degree of transparency should be put in place.

5. Define baseline and performance indicators

Provision of funding for socio-economic and/or environmental challenges is increasingly subject to measurement of outcomes (which often emerge over longer periods of time). This means careful setting of baselines for performance indicators is key. Project milestones should also be agreed by all partners and key stakeholders from the start to avoid unrealistic expectations and/or use of inappropriate conventional measurements. Joint initiatives to solve complex issues require patience, commitment and good monitoring. And an “agile” way of working, where plans and tactics can be continuously adapted is a sound basis for shaping governance and management.

6. Never compromise on customer experience

In the contexts we have discussed, partnerships can readily fall into the trap of thinking that any solution is better than no solution. Too often “doing good” for society and the environment has led to market failure. It is assumed that socially or environmentally valuable solutions require a sacrifice in terms of the quality, performance, and user experience. On the contrary, such solutions should offer better quality, a higher level of performance and a better experience than current ones. It is a matter of doing well (building a loyal customer base by delivering a great experience) as well as doing good (delivering results on commitments to solve significant societal issues).

This requires all key stakeholders and partners to participate in setting clear performance and quality targets using a top-down and bottom-up approach that creates a sense of ownership in the solution. In addition, the use of people-focused research tools and design-thinking methodologies can help in gathering deep, qualitative insights and co-creation of context-specific value propositions able to deliver the desired user experiences.

7. Leverage learning in contexts with similar challenges and conditions

For most companies, experimenting with opportunities in the Transformation Economy starts gradually. Capturing and leveraging lessons from successes and failures (together with the partners involved) helps to ease the way to new opportunities in other contexts with similar challenges and conditions. This allows the network to continue to extend its market for value delivery and to build on its experience. It may also increase the attractiveness of new partners for similar ventures in different settings.

Final word

The Transformation Economy offers tremendous scope: turning social and environmental issues into business opportunities that can make brands more meaningful and respected, and it can generate long lasting revenue. Furthermore, working towards outcomes with a sense of purpose can motivate and engage employees. But there are no business models to “cut and paste”, and value creation partnerships require an investment in time and resources. Nonetheless such partnerships offer a platform for loyalty and strong customer engagement which is very different from today’s business environment where propositions are easily copied and under constant price pressure.

We believe the way forward is first to create awareness and stimulate interest in issues that may resonate within your organisation. It’s a matter of finding the right opportunities that you can leverage to build capacity and relationships to succeed in this new paradigm. Internal organisational transformation is as important as external. Breaking down silos and creating multi-disciplinary platforms able to participate in value sharing network initiatives is essential. Companies can only inspire external stakeholders and partnerships if they themselves radiate passion, commitment, and a spirit of collaboration to solve challenges and to transform how value is created and shared.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Dr. Simona Rocchi is Senior Design Research Director in Innovation and Sustainability at Philips Design. She manages the creative direction of strategic design initiatives, and she oversees multi-stakeholder collaborative activities in emerging markets. Simona holds a PhD in Sustainability, an MSc. in Environmental Management and Policy and an MSc. in Architecture.

Dr. Simona Rocchi is Senior Design Research Director in Innovation and Sustainability at Philips Design. She manages the creative direction of strategic design initiatives, and she oversees multi-stakeholder collaborative activities in emerging markets. Simona holds a PhD in Sustainability, an MSc. in Environmental Management and Policy and an MSc. in Architecture.

Dr. Bahaa Eddine Sarroukh is Head of the Philips Africa Innovation Hub in Kenya. He focuses on developing innovations within the African ecosystem. He has built leadership in innovation in low resource settings, and recently developed the Philips Community Life Center approach. He holds a PhD in Signal Processing and Applied Mathematics.

Dr. Bahaa Eddine Sarroukh is Head of the Philips Africa Innovation Hub in Kenya. He focuses on developing innovations within the African ecosystem. He has built leadership in innovation in low resource settings, and recently developed the Philips Community Life Center approach. He holds a PhD in Signal Processing and Applied Mathematics.

Karthik Subbaraman is a healthcare professional with clinical and managerial experience in emerging and developed markets. A thought-leader in healthcare requirements and solutions in Sub-Saharan Africa and India, Karthik is engaged in consultancy projects with governments and global organisations to design and deploy clinical and operational workflows in primary care.

Karthik Subbaraman is a healthcare professional with clinical and managerial experience in emerging and developed markets. A thought-leader in healthcare requirements and solutions in Sub-Saharan Africa and India, Karthik is engaged in consultancy projects with governments and global organisations to design and deploy clinical and operational workflows in primary care.

Luc De Clerck manages the Philips CLC program in the African Innovation Hub. At Philips, he has conducted clinical studies in emergency obstetrics with South African universities and implemented an emergency obstetrics program with the WHO and the Namibian government. He also manages healthcare delivery strengthening initiatives with private and public partners in Africa and South Asia.

Luc De Clerck manages the Philips CLC program in the African Innovation Hub. At Philips, he has conducted clinical studies in emergency obstetrics with South African universities and implemented an emergency obstetrics program with the WHO and the Namibian government. He also manages healthcare delivery strengthening initiatives with private and public partners in Africa and South Asia.

Dr. Reon Brand is a Senior Research Director in Foresight, Socio-cultural research and Innovation Strategy at Philips Design. He focuses on the exploration of emerging socio-economic paradigms and leads initiatives related to systemic transformative change. He has a PhD in molecular biology from the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Dr. Reon Brand is a Senior Research Director in Foresight, Socio-cultural research and Innovation Strategy at Philips Design. He focuses on the exploration of emerging socio-economic paradigms and leads initiatives related to systemic transformative change. He has a PhD in molecular biology from the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

References

1. UN (2015) “Sustainable Development Goals – 17 goals to transform our world”, 25 September. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

2. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development website (2014) Developing countries face $2.5 trillion annual investment gap in key sustainable development sectors, UNCTAD report estimates – http://unctad.org/en/pages/PressRelease.aspx?OriginalVersionID=194

3. Eggers, W. D., Macmillan, P. (2013) The Solution Revolution. How Business, Government and Social Enterprises are Teaming Up to Solve Society’s Toughest Problems. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

4. World Economic Forum (2016) Health System Leapfrogging in Emerging Economies. Ecosystem of Partnerships for Leapfrogging, a report produced in collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group, May.

5. Interface website (2016) “The Interface Story”– http://www.interfaceglobal.com/Sustainability/Interface-Story.aspx

6. The Natural Step website (2017) “Case Study: Interface”– http://thenaturalstep.nl/project/interface/

7. Interface website (2016) “The Interface Story”– http://www.interfaceglobal.com/Sustainability/Environmental-Footprint/Waste.aspx

8. Danone Communities website (2016) “Addressing malnutrition and access to safe drinking water through social business incubator”– http://www.danone.com/en/for-all/sustainability/unique-business-approach/danone-communities/

9. YouTube (2014) “An interview on social business with Franck Riboud”, former Chairman and CEO, Danone Group – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hC5Wz3_tnnA

10. Yunus Social Business Blog (2016) “Grameen-Danone Foods Ltd” – Nutrition http://www.yunussb.com/blog/category/case-studies/

11. The Grameen Creative Lab website (2016) “Grameen Danone Foods Ltd”– http://www.grameencreativelab.com/live-examples/grameen-danone-foods-ltd.html

12. Yasmin, N. N. (2016) Sustainability of a Social Business: A Case Study on Grameen Danone Foods Limited in Asian Business Review, Vol 6, n.3, 18 December http://journals.abc.us.org/index.php/abr/article/view/887

13. The Grameen Creative Lab website (2016) “Grameen Danone Foods Ltd”– http://www.grameencreativelab.com/live-examples/grameen-danone-foods-ltd.html

14. The Grameen Creative Lab website (2016) “Grameen Danone Foods Ltd”– http://www.grameencreativelab.com/live-examples/grameen-danone-foods-ltd.html

15. Sustainable Development Goals and the post-2015 agenda: A Business Manifesto signatories including Unilever and Philips (2015)– https://www.unilever.com/Images/sustainable-development-goals-and-the-post-2015-agenda-business-manifesto-january-2015_tcm244-423602_en.pdf

16. Unilever website (2017) “UN Global Goals for Sustainable Development” – https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/the-sustainable-living-plan/our-approach-to-reporting/sdg/

17. Wash4Work website (2016) “WASH4WORK”- https://wateractionhub.org/wash4work/

18. Unilever website (2014) – “Joining forces to tackle the sanitation crisis” – https://www.unilever.com/news/news-and-features/Feature-article/2014/Joining-forces-to-tackle-the-sanitation-crisis.html

19. Unilever website (2017) – Lifebuoy Mumbai trial

20. Unilever website (2015) – “Lifebuoy way of life. Towards universal handwashing with soap: Social Mission Report” – https://www.unilever.com/Images/lifebuoy-way-of-life-2015_tcm244-418692_en.pdf

21. Rodrigues J., Baker, G. A. (2012) Grameen Danone Foods Limited (GDF) in IFAMA (International Food and Agribusiness Management Review), Vol. 15, issue 1, January-https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227366476_Grameen_danone_foods_limited_GDF

22. Yasmin, N. N. (2016) Sustainability of a Social Business: A Case Study on Grameen Danone Foods Limited in Asian Business Review, Vol 6, n.3, 18 December http://journals.abc.us.org/index.php/abr/article/view/887

23. Vodafone website (2016) “M-Pesa reaches 25 million customers milestone”, 25 April 2016 – https://www.vodafone.com/content/index/media/vodafone-group-releases/2016/mpesa-25million.html

24. YouTube (2013) “The Story of M-Pesa” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i0dBWaen3aQ

25. KPMG (2016) “Case study: Integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into Safaricom’s Corporate Strategy” – https://home.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/07/za-safaricom-case-study.pdf

26. Philips (2017), Philips Global Website –

27. Philips (2017) “Philips Partners with the Government of Kenya and the United Nations to improve access to primary healthcare in Africa”, Philips Media, May 2 – http://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/press/2017/20170502-philips-partners-with-the-government-of-kenya-and-the-united-nations-to-improve-access-to-primary-healthcare-in-africa.html

28. Philips (2017) “Introducing the Community Life Center platform”, Philips Website –http://www.philips.com/a-w/about/sustainability/healthy-people/supporting-communities/fabric-of-africa/programs/philips-community-life-project.html

29. Philips (2016) “The Philips Community Life Center approach” video in YouTube, December 2 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxEe1zfSpFI&t=58s

30. Philips (2014) “Philips inaugurates Africa’s first Community Life Center aimed at strengthening primary health care and enabling community development”, October 3 – http://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/press/2014/20141003-Philips-inaugurates-Africas-first-Community-Life-Center-aimed-at-strengthening-primary-health-care-and-enabling-community-development.html

31. Goin, J. (2014) “Philips innovative clinic opens in Kiambu county” in Capital News, October 4 – http://www.capitalfm.co.ke/news/2014/10/philips-innovative-clinic-opens-in-kiambu-county/

32. Philips (2016) “Philips and UNFPA collaborate to transform lives in Mandera County, Kenya – announce plans to implement Kenya’s second Community Life Centre”, May 12 – http://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/press/2016/20160512-philips-and-unfpa-collaborate-to-transform-lives-in-mandera-county-kenya.html

33. Business Daily (2016) “Philips plans Mandera healthcare centre to reduce cost burden”, May 12 – http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/economy/Philips-plans-Mandera-healthcare-centre/3946234-3201086-yuibj3/index.html

34. Chatterjee, S. (2015) “We can change the story of Mandera”, October 22 – https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2000180345/we-can-change-the-story-of-mandera

35. UNFPA (2014) “Kenya Counties with the Highest Burden of Maternal Mortality”, 13 August – http://kenya.unfpa.org/news/counties-highest-burden-maternal-mortality

36. Philips (2017) “The first Philips Community Life Center (CLC) in the DRC” in YouTube, January 18 –https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qg7OeHkJ04w

37. Philips (2017) from figures provided by the local Health Information Management System in Githurai used to report to the District level (2) on a monthly basis.