By Simon L. Dolan, Kyle Brykman and Shay S. Tzafrir

Every leader needs to inspire trust in their followers, employees, and stakeholders. Trust is one concept that binds all efforts at relationship-building together, leading to business success. In this article, three experts in business management discuss how leaders can build trust.

Introduction

Trust is the foundation of any successful relationship, whether it be personal or professional. Building trust requires effort and time, but the benefits of a trustworthy relationship are immeasurable. Trust can lead to increased communication, better collaboration, and a stronger sense of community. In this article, we will explore the strategies and techniques available to leaders that can be used to establish trust in their relationships.

Trust is an essential concept in many of the articles, books, and research focus of the coauthors of this article. Dolan (2011 and 2020), for example, refers to TRUST as the “Super-Value”, the “Value of Values” or the “Mother of all Values”.1 Garti and Tzafrir (2022), in a recent book, suggests trust to be a powerful concept for synchronising work-family relationships.2 As researchers, consultants, and change agents, we argue that a leader who wishes to be effective in his/her role needs to embed the triple anchors in his/her toolbox: 1) A clear definition of what trust means (and what trust is not), 2) a clear methodology to assess trust, and 3) evidence-based tool (or tools) to assess the genuine level of trust that he/she experiences. We therefore believe that the time is ripe to explore these three components, which we have been researching for over 20 years. This is needed because managers, leaders, and employees across organisations frequently use the term trust, even though it is not very well understood, and neither is it clear as to how to build it and what measures/tools are available to enhance it.

Enhancing trust in organisations is a complex and challenging process that requires a well-planned methodology and effective tools to achieve success. Trust is the foundation of any healthy and productive relationship. Without trust, employees can feel disengaged and unmotivated—resulting in a decline in productivity or quitting the organisation. It may also lead to overall poor organisational performance.

However, enhancing trust within an organisation is not an easy task. It requires a significant investment of time and effort, along with the right “know-how”. Leaders must not only be committed to creating a culture of trust and be willing to make difficult decisions to achieve this goal, but also have a firm understanding of how to do so and what works against trust. Additionally, trust takes time to build, and it can be easily lost if not nurtured and maintained.

The objective of this paper is threefold: (1) to shed light on what trust means in organisational contexts (2) to describe a 360o methodology to assess the leaders´ trust (ranging from self-trust, subordinates´ trust in the leader, and colleagues´ trust in the leader), and (3) to describe the latest applications of the TRUST-ME tool that can be used as a gamification tool and online assessment.

So, what exactly is TRUST?

Trust is about having confidence in someone or something. Trust is about believing that they will do what they say they will do, it is the ability to reduce uncertainty as a result of a shared positive history, and that they have your best interests at heart.3 However, trust can mean different things to different people. For some, it may be about reliability and consistency. For others, it may be about honesty and transparency. And for others still, it may be about a sense of connection and understanding. One clear thing, though, is that trust is vital to any relationship, whether it is personal or professional. Without trust, it is difficult to build strong, lasting connections with others and hard to feel secure and confident in your interactions with them.

Some regard or consider trust as a concept with two components: trustfulness and trustworthiness. This approach combines the attitude of one actor with the characteristics of another. A host of scholars stress the importance of being trustful. In the idealistic tradition, faith and social education nurturing positive expectations are the keys to trust and cooperation. However, trustworthiness can play a major role in this attitude. Overly optimistic or deceitful promises will fool and disappoint the trustful actor, making him/her distrustful, while the experience of trustworthy partners will enhance further cooperation. Hence, the degree of trustworthiness is the central factor for whether trust increases or decreases.4

Mind you, trustfulness refers to the willingness to trust others and to believe in their intentions and actions without questioning them. It is a positive trait that allows individuals to build strong relationships and foster collaboration. Trustfulness is often associated with openness and vulnerability, as it requires individuals to let their guard down and rely on others. On the other hand, trustworthiness refers to the ability to be trusted, and to act in a reliable and honest way that inspires confidence in others. It is a character trait that is built over time through consistent behaviour and actions. Trustworthiness is often associated with integrity and responsibility, as it requires individuals to be accountable for their actions and to follow through on their commitments. It also involves compassion and benevolence, as one needs to believe that others will act with kindness and with their best interest in mind.

While trustfulness and trustworthiness are both important, they are not interchangeable. Trustfulness can be a positive quality, but it can also be risky if it is not accompanied by discernment and caution. Blindly trusting others, unconditional trust, can lead to disappointment and even harm if the other person proves to be untrustworthy. On the other hand, trustworthiness is a foundational quality that underpins all healthy relationships. Without trustworthiness, trust cannot be built or maintained. Trustworthiness requires individuals to be honest, reliable, and consistent in their behaviour, even when it is difficult or inconvenient.

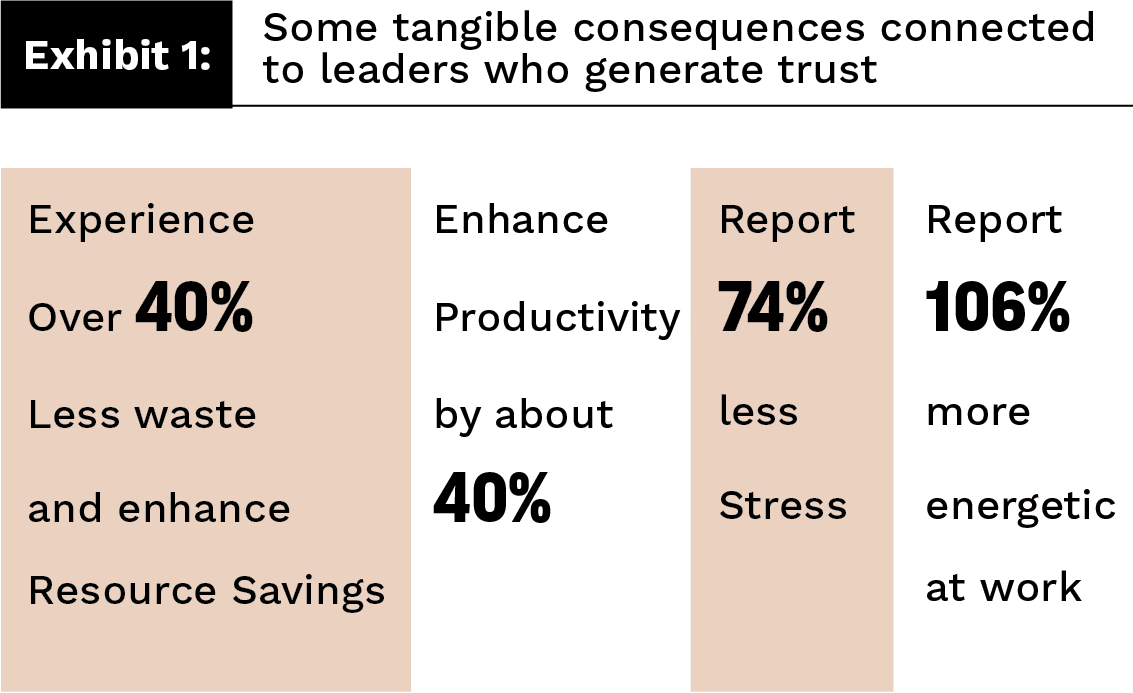

All in all, research shows that leaders who display trust, create a positive culture which makes a huge difference in terms of the commitment and productivity of members of the organisation (See Exhibit 1).

The Spiritual Dimension of Trust

Is there such a thing as spiritual trust? The answer is yes. Among the types of trust, it focuses on faith and religious doctrine. People with this type of trust believe in the spiritual energy that surrounds human beings. It is a very subjective trust that depends on the context and culture.

The phrase “In God We Trust” is a well-known and significant motto in the United States. It is printed on its currency, displayed in government buildings, and has been a part of the US national identity for over 150 years. Despite its origins in wartime and Cold War politics, the motto has endured as a symbol of American values and identity. Regardless of one’s personal beliefs, the phrase “In God We Trust” remains an important part of the US national heritage. It represents its history, values, and commitment to a higher power. And it serves as a reminder that, even in times of hardship and division, one can find strength and unity in one’s faith. Moreover, the phrase is a testament to the importance of faith and spirituality in American life. It acknowledges that religion and spirituality are not just personal beliefs, but also a fundamental part of the nation’s heritage and culture. It is a call to embrace one’s faith and to seek guidance from a higher power in times of need.

The biological and neuroscience base of Trust

We are born to trust — to engage with others and rely on them for survival. This innate human condition served critical evolutionarily purposes in early hunter-gatherer societies that depended on collaboration and concern with non-familial members.

The neuroscience base of trust is a fascinating topic that explores the intricacies of the human brain and its ability to build and maintain trust. The neuroscience of trust is based on the understanding of the brain’s reward system, which is responsible for regulating our emotions and behaviours. Studies have shown that when we trust someone, our brains release oxytocin, a hormone that is associated with social bonding and attachment. This chemical reaction creates a sense of warmth, closeness, and intimacy, which reinforces the bond of trust between individuals.

Furthermore, the prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain responsible for decision-making and social behaviour, is also involved in the process of building trust. This area of the brain is responsible for evaluating social cues and determining whether someone is trustworthy. When we encounter someone who displays trustworthy behaviour, the prefrontal cortex sends signals to the reward system, which reinforces the bond of trust.

However, the neuroscience base of trust is not limited to the reward system and prefrontal cortex. Other regions of the brain, such as the amygdala, play a crucial role in the process of building and maintaining trust. The amygdala is responsible for processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety, which can have a significant impact on our ability to trust others. When we encounter a potential threat, the amygdala sends signals to the prefrontal cortex, which evaluates the situation and determines whether it is safe to trust the other person.

In conclusion, the neuroscience base of trust is a complex and multifaceted topic that involves a combination of cognitive, emotional, and social processes. It highlights the importance of social bonding and attachment in human relationships and provides insight into the mechanisms that underlie trust. By understanding the neuroscience of trust, we can develop a greater appreciation for the power of trust in our lives and work towards building stronger, more meaningful relationships with others.5

The costs and consequences of mistrust in an organisation’s leader

Today, mistrust has become a pervasive issue that has far-reaching consequences. In organisations, mistrust can create an environment of fear, doubt, and uncertainty. The costs of mistrust are significant, as it can lead to a breakdown in communication, a lack of collaboration, and ultimately, a loss of productivity.

In the workplace, mistrust can be equally damaging. It can create a toxic environment where employees feel suspicious of one another, and where collaboration is difficult to achieve. Mistrust can lead to a lack of innovation and creativity, as employees are hesitant to share their ideas and opinions for fear of being judged or criticised. It is difficult to recover from mistrust, as research shows that it takes approximately six trust-building actions to compensate for one act that breached trust.6

Mistrust in the workplace can have serious consequences for both employees and the organisation. Firstly, mistrust can lead to a toxic work environment. When employees don’t trust their leader, it creates a culture of suspicion and paranoia. This leads employees to feel isolated and unsupported, which can have a negative impact on their mental health and well-being. A toxic leader can also lead to high turnover rates, as employees may feel compelled to escape the negative atmosphere.

Secondly, mistrust in the leadership of an organisation can decrease productivity. When employees don’t trust each other, they do not collaborate or communicate effectively leading to avoidable mistakes. When employees don’t feel comfortable working with their leaders, they may also be less likely to ask for help, which can further decrease productivity.

Thirdly, when employees lack trust in their leader, they feel unsupported and undervalued. This leads to a lack of motivation and enthusiasm for their work, which ultimately impacts their performance. When employees are unhappy in their jobs, it can also lead to increased absenteeism and presenteeism, which can further impact the organisation’s bottom line.

The paradox of employing “inward-trust¨ but “outward- zero trust”

So far, we have argued that trust is a valuable commodity. It is especially important to nourish it within the people that work in the same team or organisation. We call it “inward trust”. But, with the rise of cyber-attacks and political turmoil, it is becoming increasingly difficult to rely on others. That’s where the concept of “Zero Trust” comes in. This approach to security is gaining popularity in both international politics and the digital security sector. The idea behind Zero Trust is simple: trust no one. This means that every user, device, and application must be verified and authenticated before being granted access to a network or system. It also means that access is granted on a need-to-know basis, rather than blanket permission.

While the concept of Zero Trust may seem extreme, it is becoming necessary in today’s world. Cyber-attacks and political turmoil are on the rise, and trust is becoming harder to come by. Zero Trust provides a solution to these problems by ensuring that every user, device, and application is verified and authenticated before being granted access. This is a small price to pay for the security of sensitive information and the protection of our democracy.

Leadership and Trust: The usefulness of the TRUST-ME scale and tools

When it comes to measuring trust, it is important to consider the various factors that contribute to its formation. To measure trust, various concepts and scales have been developed. These include the Trust Scale, the Trust in Organisations Scale, and the Interpersonal Trust Scale, among others. These scales are designed to assess different aspects of trust, such as trust in specific individuals, trust in organisations, and trust in oneself.

Many of the conflicts in organisations arise because leaders cannot generate and/or sustain trust. How can a leader have followers if they do not trust him/her? Unfortunately, research suggests that in more and more companies (families included if we use it as a metaphor for an organisation), it seems that people have lost trust in their leaders and their peers. We note this lack of trust in businesses, government agencies, education, and even in our churches (you only must listen to the scandals that are published on the corrupt behaviour of some priests). This general distrust in our leaders points to a cultural breakdown. The problem is not a lack of leaders but a lack of a climate of trust where leadership is possible.

Unless followers feel confident in the fairness and reliability of their leaders, they will not continue following them. Trust can significantly alter individual and organisational effectiveness. Trust, more than power and hierarchy, is what makes an organisation work effectively.

So, if we know that trust is a prerequisite for any attempt by the leader to change the organisational culture and to sustain the reliability, motivation, and behaviour of the followers, why don’t we help leaders to improve trust? In our opinion, people use the word trust too often in making a generic reference and therefore until we have a clear metric to measure it, we will continue to operate without a compass. The consequence is simple: the more a leader uses the word trust (without precision), the more the followers and companions will lose interest in listening to him/her and it will naturally lead to disappointment in our leaders.

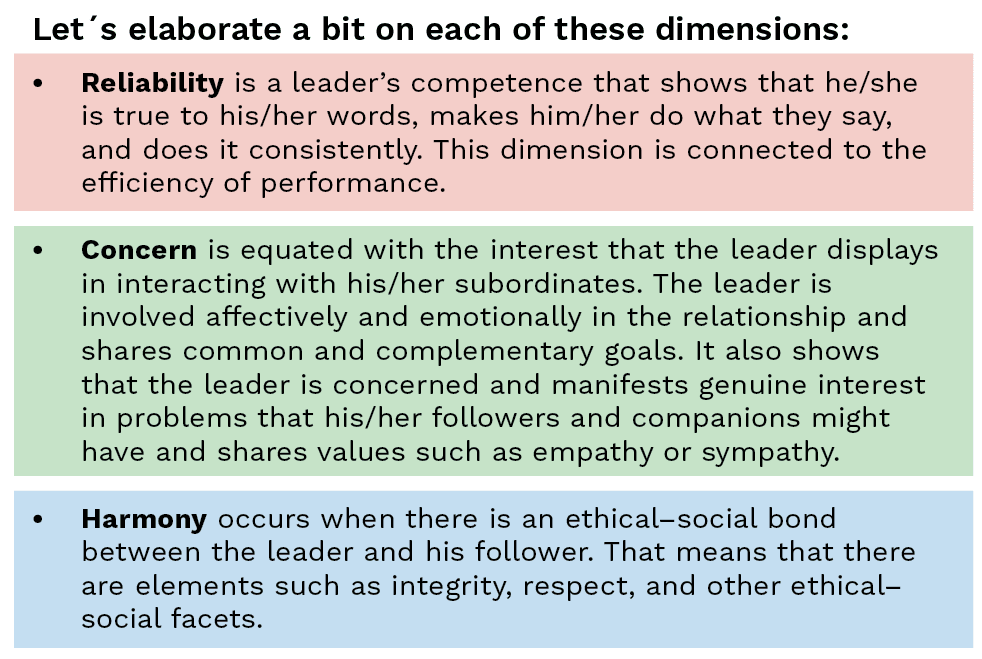

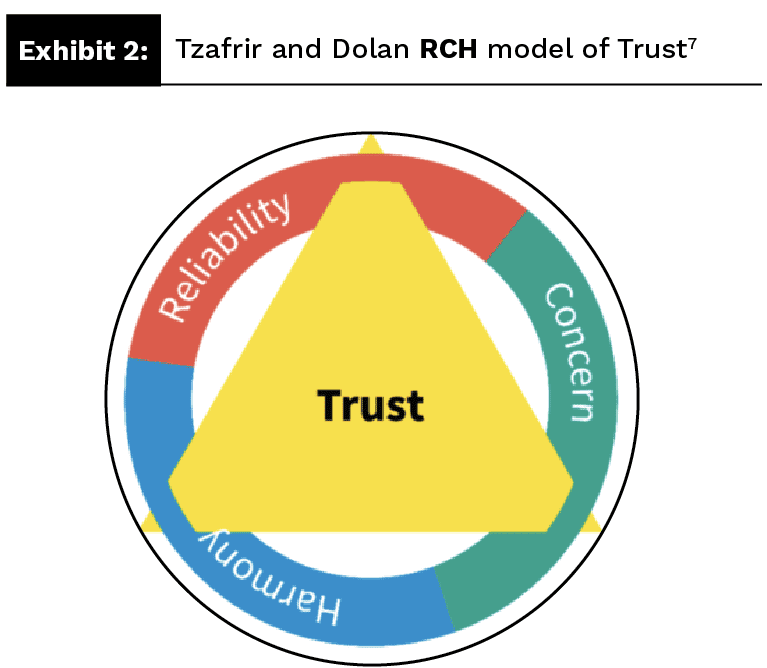

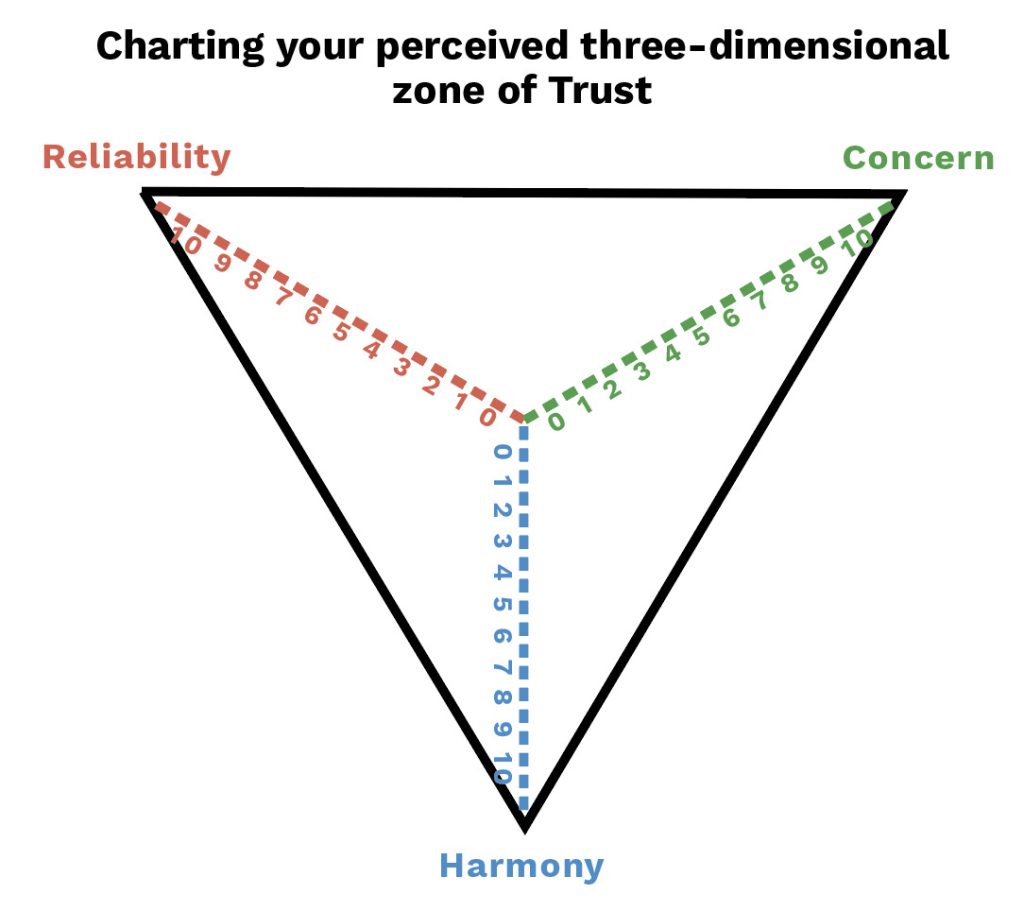

For this reason, at the beginning of the 2000s, we began to study trust in work settings, in a rigorous and systematic way. In 2004, we published for the first time an article where we identified the three key dimensions of the concept of trust (acronym RCH), as we refined the tools to measure it. The three dimensions that emerged from the numerous scientific studies were:

Reliability, Concern, and Harmony (See Exhibit 2).

Trust assessment: A demonstration of tools that are based on (a) gamification (b) digital online

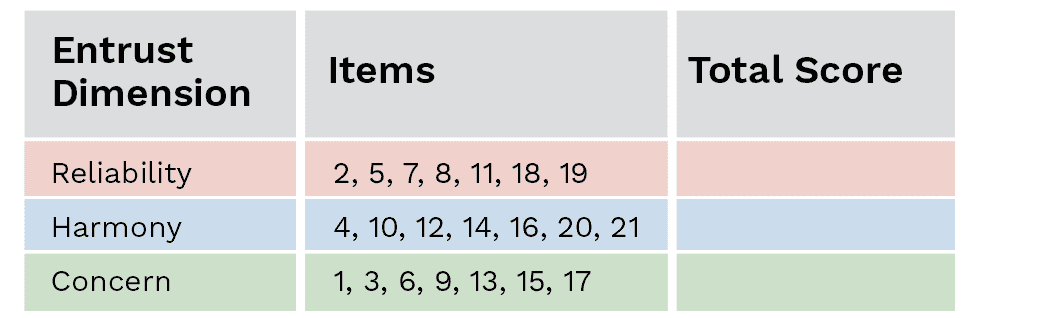

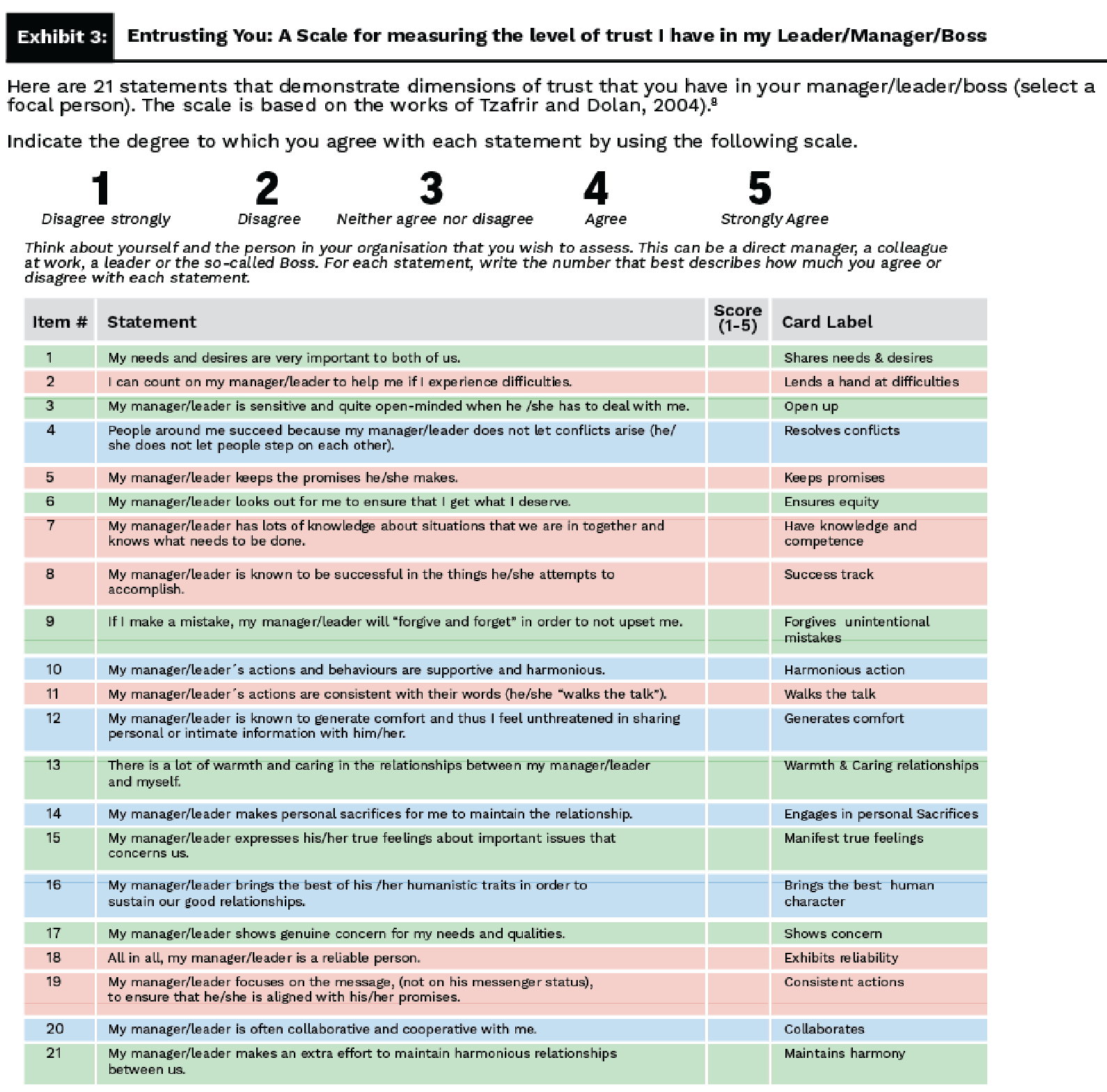

Entrusting my leader assessment and calculating the trust scores in each dimension is provided in Exhibit 3.

Interpreting the results

Calculate your total score by adding the following items.

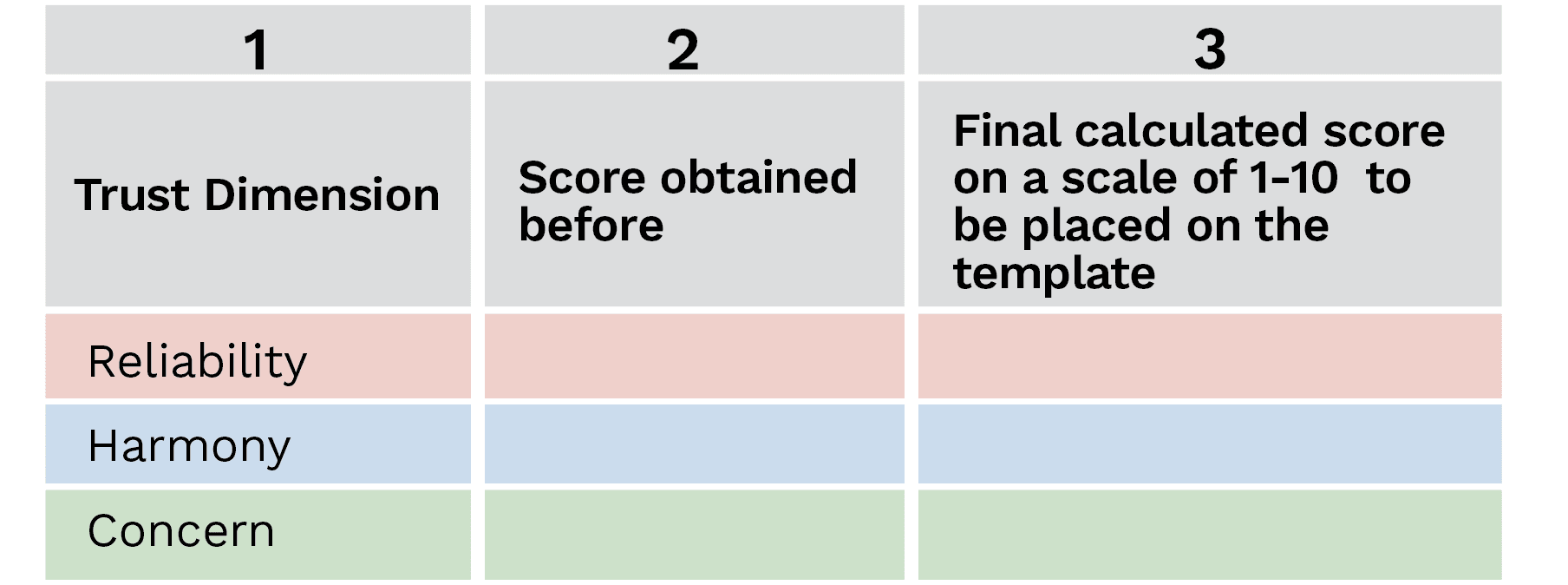

- Please retake the scores obtained before and place them respectively for each dimension in column 2.

- Take your score and divide it by 7 and then multiply each by 2, then place each of them in Column 3 respectively. This will generate a final score on a scale ranging from 1-10 to be used in the Template.

Now, mark your final score on each of the corresponding dimensions in the three-dimensional ENTRUST template. Once marked, connect the dots with a straight line. Please shade the area. This is your perceived TRUST zone with the person that you are assessing.

The Trust Kit9

The Trust Kit was developed to perform the same exercise as in Exhibit 3 but in a fun and interactive fashion. Research shows that this gamification approach tends to yield more effective results than simple explanations of principles by tapping into psychological and motivational aspects of human behaviour. The Trust Kit contains 21 cards (in alignment with the 21 questions), each of which corresponds with a dimension of the RCH model, with a distinct colour background. Seven cards are Red (representing Reliability), 7 Cards are Green (representing Concern), and 7 cards are Blue (representing Harmony). Players select cards in accordance with the person being assessed (boss, manager, or leader) and place it on the mate (Exhibit 4).

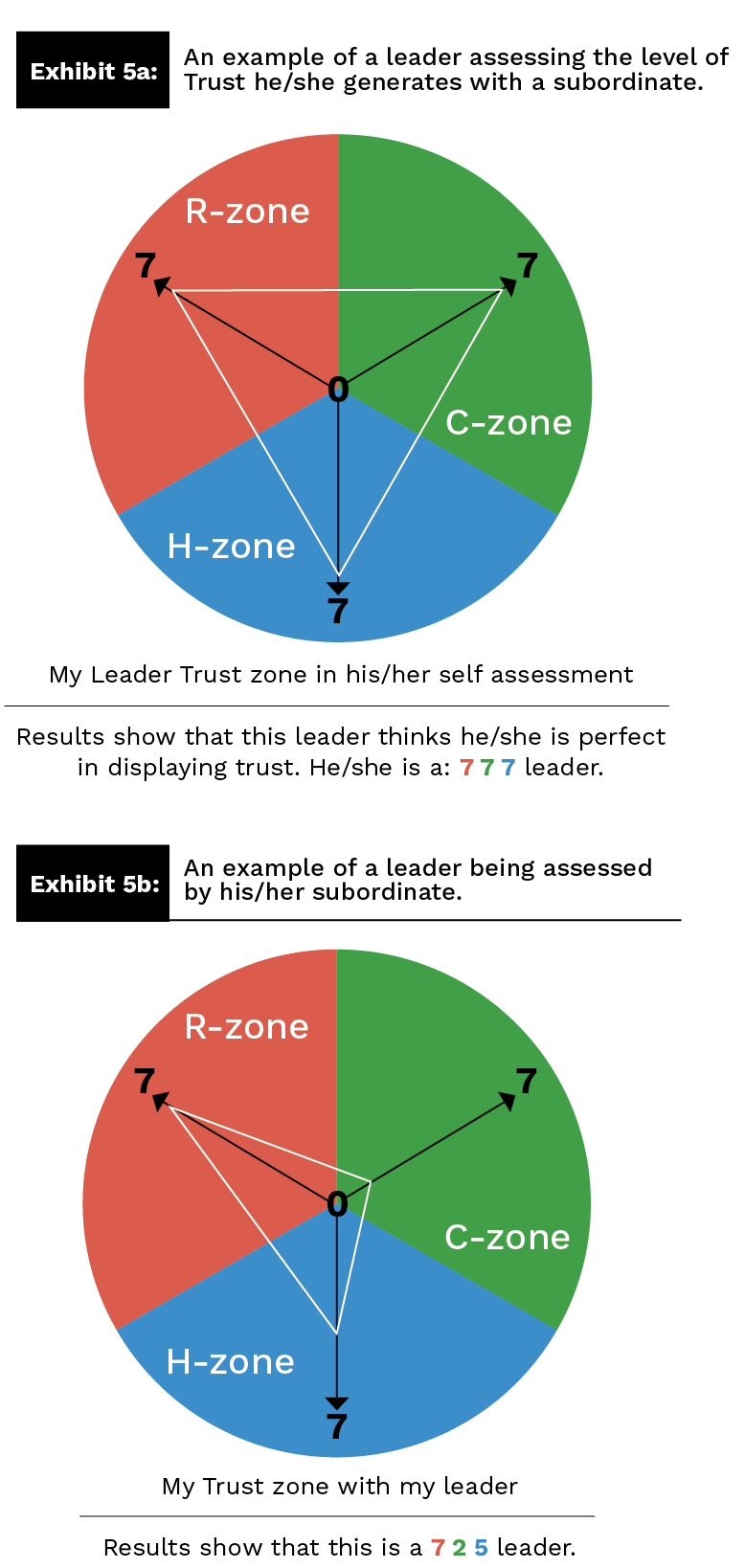

When you compare the two assessments, and can also see the gap visually, you get an idea of what needs to be worked on to improve the level of trust between a leader and a subordinate. You can add more assessment in the 360o patterns, to identify more gaps (with a team, with peers, etc.,) thereby improving the diagnosis. This will be a cumbersome process, and this is the reason for the development of the digital tool that is described in the next section.

A digital online tool to assess trust in the organisation

The Digital Trust Assessment has been developed as part of a programme and philosophy called “Leadership by Values®”. This programme provides stakeholders with the ability to evaluate their leaders in three areas: 1) assess their core values and measure how well they fit with the organisation’s culture, 2) assess their competencies and leadership skills for future success (9 skills total), and 3) assess their overall state of trust. The programme, which incorporates some features of Artificial Intelligence, assesses each of these leadership skills in a 360-degree degree, and uses information on:

- Leader’s self-assessment of the level of trust they generate. (RCH model)

- Subordinates (one or many) aggregate assessment of the leader’s level of trust (RCH Model).

- Aggregate assessment of leaders’ “peers” (RCH Model), and

- Aggregate assessment of the leader’s superior(s) (RCH Model)

- At the end of this process, an elaborate automatic (AI-based) report is generated which indicates (a) the diagnosis, (b) the gaps, and (c) the areas for improvement to enhance this important phenomenon of building mutual trust.

A futuristic note and prediction about the role of trust

In a futuristic vision, the importance of trust in our lives will be more crucial than ever before. As we progress into an era of advanced technology and interconnectedness, trust will shape the very fabric of our society, economy, and personal relationships.

One aspect where trust will play a significant role is in the realm of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation. As machines become increasingly integrated into our daily lives, trust will be essential for us to embrace and fully benefit from these advancements. We will need to trust that AI systems are reliable, secure, and make ethical decisions. Trust will enable us to delegate tasks to machines without fear of them malfunctioning or causing harm.

In economic terms, trust will be the foundation of a thriving digital marketplace. With the rise of decentralised technologies like blockchain, trust will be inherent in every transaction. People will have the confidence to engage in online commerce, knowing that their personal and financial information is secure. This trust will foster global trade and enable individuals from different corners of the world to interact and engage in mutually beneficial exchanges.

Moreover, in a future where virtual reality and augmented reality become more prevalent, trust will be vital to foster meaningful connections. As we immerse ourselves in digital realms, we will rely on trust to distinguish between genuine interactions and deceptive simulations. Trust will be the bridge that allows us to form deep and authentic relationships, whether they are virtual or physical.

Furthermore, trust will be the backbone of governance and societal systems. In a world where data is the new currency, individuals will need to trust that their personal information is handled responsibly and transparently by governments and corporations. Trust will be crucial to maintain social harmony and ensure that power is not abused.

Ultimately, in this futuristic vision, trust will be the currency that fuels progress and enables us to navigate the complexities of an interconnected world. It will determine our ability to embrace technological advancements, participate in the digital economy, form meaningful connections, and maintain a just and equitable society.

In short, trust will be the cornerstone of our lives in the future. Its importance will extend beyond personal relationships, permeating every aspect of our existence. As we navigate a world shaped by advanced technology, trust will be the glue that holds our society together and allows us to fully embrace the opportunities and challenges of the future.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored the concept of trust in all its complexities. We wish to reiterate that trust is one of the most widely used constructs around the world, but it is poorly understood, defined, and measured.

We were trained to think that if any concept is missing these qualities (definition, methodology on how to use it, and metrics) it is useless. An attempt was therefore made to define trust, to look at its dimensions, and to show clearly how it can be applied. We have decided to adopt the RCH three-dimensional Trust model because it was based on empirical research and seems to be used by thousands of researchers around the world.

In the article, we introduced the essence of the RCH model and explored its potential use wherever leadership is called for: at home, at work and in the community. And finally, we introduced three tools for measuring trust, which can all be used in different contexts, and, if necessary, in 3600. This allows you to measure your leader’s trust either manually, or via the use of a gamification tool or digitally. Gaps between the leader and other stakeholders can be easily detected, displayed, and discussed resulting in the preparation of strategic solutions to enhance trust, which in the end, is a win-win outcome.

About the Authors

Simon L. Dolan is a full professor and senior researcher of HRM and Work Psychology at Advantere School of Management (affiliated with Comillas, Duesto and Georgetown Universities). A former Future of Work Chair at ESADE Business School, he has published 85 books (in multiple languages) and over 150 articles in referees’ journals. He is also the co-founder and President of the Global Future of Work Foundation. His work, consulting and research are about values, leadership, coaching, stress management and resilience as well as issues connected to the future of work. He is a member of the editorial board of half a dozen scientific journals. His full bio at: www.simondolan.com

Simon L. Dolan is a full professor and senior researcher of HRM and Work Psychology at Advantere School of Management (affiliated with Comillas, Duesto and Georgetown Universities). A former Future of Work Chair at ESADE Business School, he has published 85 books (in multiple languages) and over 150 articles in referees’ journals. He is also the co-founder and President of the Global Future of Work Foundation. His work, consulting and research are about values, leadership, coaching, stress management and resilience as well as issues connected to the future of work. He is a member of the editorial board of half a dozen scientific journals. His full bio at: www.simondolan.com

Kyle Brykman is an Assistant Professor of Management and the VPRI Early Career Research Chair in Leadership at the Odette School of Business, University of Windsor. Kyle’s mission is to help people lead happier, healthier, and more productive lives, which he accomplishes through high-quality research, evidence-based teaching, and engaging training and coaching. Kyle’s research focuses on employee voice and interpersonal team dynamics. He holds a PhD in Management (Organizational Behavior) from Smith School of Business at Queen’s University, an MSc in Management from Wilfrid Laurier University, and an HBA from Ivey School of Business.

Kyle Brykman is an Assistant Professor of Management and the VPRI Early Career Research Chair in Leadership at the Odette School of Business, University of Windsor. Kyle’s mission is to help people lead happier, healthier, and more productive lives, which he accomplishes through high-quality research, evidence-based teaching, and engaging training and coaching. Kyle’s research focuses on employee voice and interpersonal team dynamics. He holds a PhD in Management (Organizational Behavior) from Smith School of Business at Queen’s University, an MSc in Management from Wilfrid Laurier University, and an HBA from Ivey School of Business.

Shay S. Tzafrir is the dean of teaching and professor at the School of Business Administration, University of Haifa. A former director of the Center for the Study of Organizations & Human Resource Management, he received his Ph.D. and M.Sc. in behavioural science from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology and earned a B.A and M.A. in political science, as well as LLB, all from the University of Haifa. He serves as a member of the Editorial Review Board in Human Resource Management. He specialises in issues of people management and trust, focusing on the efficiency aspects of human capital. His current research interests include the role trust plays in various organisational factors such as strategic human resource management, organisational performance, and service quality.

Shay S. Tzafrir is the dean of teaching and professor at the School of Business Administration, University of Haifa. A former director of the Center for the Study of Organizations & Human Resource Management, he received his Ph.D. and M.Sc. in behavioural science from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology and earned a B.A and M.A. in political science, as well as LLB, all from the University of Haifa. He serves as a member of the Editorial Review Board in Human Resource Management. He specialises in issues of people management and trust, focusing on the efficiency aspects of human capital. His current research interests include the role trust plays in various organisational factors such as strategic human resource management, organisational performance, and service quality.

References

- Dolan S.L. (2011). Coaching by Values. iUniverse; Dolan S.L. (2020). The Secrets of Coaching and Leading by Values. Routledge.

- Garti, A., & Tzafrir, S. (2022). Work–Family Triangle Synchronization: Employee, Manager, and Spouse. De Gruyter.

- See: Tzafrir, S. S., & Dolan, S. L. (2004). Trust Me: A Scale for Measuring Manager-Employee Trust. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 2(2), 115-132.

- See: Tullberg J., (2008) Trust—The Importance of Trustfulness versus Trustworthiness, The Journal of Socio-Economics, Vol 37(5): 2059-2071

- In January-February 2017, Harvard Business Review published an amazing article by Paul J. Zak who covers with great details the neuroscience of trust. Highly recommended reading.

- Baumeister, R., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenaur, C., & Vohs, K. (2001). Bad Is Stronger Than Good. Review of General Psychology 323–370.

- This model was published for the first time in 2004 but was studied in other contexts many times by Tzafrir and Dolan and many other collaborators. It was tested in many cultures and sectors. Recently; ResearchGate has advised the authors that over 9000 researchers have downloaded and/or used this model in their own research; it seems that of all alternative models of trust, this one has become the most popular and most cited. To read more: Tzafrir S., Dolan S.L. (2004) Trust me: A Scale for Measuring Manager‐Employee Trust, Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, Vol. 2(2):115–132, https://do i.org/10.1 108/1 53654 30480 00050 5; Dolan S.L., Tzafrir S., Baruch Y. (2005) Testing the Causal Relationships between Procedural Justice, Trust, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Revue de gestion de ressources humanies, Vol. 57:79–89; Mach M., Dolan S.L., Tzafrir S. (2010)The Differential Effect of Team Members’ Trust on Team Performance: The Mediation Role of Team Cohesion, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 83(3):771–794 (https://d oi.or g/10. 1348/09631 7909X 47390 3); Chaluz H., Tzafrir S., Dolan S.L. (2015). Actionable Trust in Service Organisations: A Multi-Dimensional Perspective, Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 31(1):31–39; Capell B., Tzafrir S., Enosh G., Dolan S.L. (2018) Explaining Sexual Minorities’ Disclosure: The Role of Trust Embedded in Organizational Practices, Organization Studies, Vol. 39(7):947–973 https://journal s.sag epub. com/d oi /fu ll/10 .1177 /0170 84061 77080 00.

- Tzafrir and Dolan 2004. Op. Cit.

- More information on the Trust Kit is available at: learningaboutvalues.com