By Omar Abbosh, Vedrana Savic and Michael Moore

To grow their businesses consistently, leaders must envision a much bigger picture of where value resides than they have traditionally. And they must be prepared to create much more value than they can capture for themselves.

Why do so many companies struggle to identify and capture growth opportunities? The digital age is brimming with promise on this front. Yet regularly growing the portion of a company’s share price that is based on expectations of future earnings growth – while at the same time growing the portion based on actual earnings – is not the norm.1 In fact, only two percent of the 995 large organisations examined in a recent Accenture research study have accomplished this feat over the past 16 years. (See “About the Research” for more detail.)

Our research suggests two reasons why this percentage is so low.

First, while a tremendous amount of new value can result from new or advancing technologies, that value is often trapped, both within and beyond the boundaries of any single business. For example, executives often overlook opportunities in their existing enterprise to apply digital capabilities to serve customers in new ways, and thus to increase revenues (rather than to reduce costs). In their industry, value is often trapped where outdated infrastructures serve scores or even hundreds of companies and where change would upset the status quo – even though the status quo does not support accelerated adoption of new products and services. (It’s also possible that a few companies in any given industry are already benefiting from innovations that, if shared, could serve many more and grow the pie for everyone.)

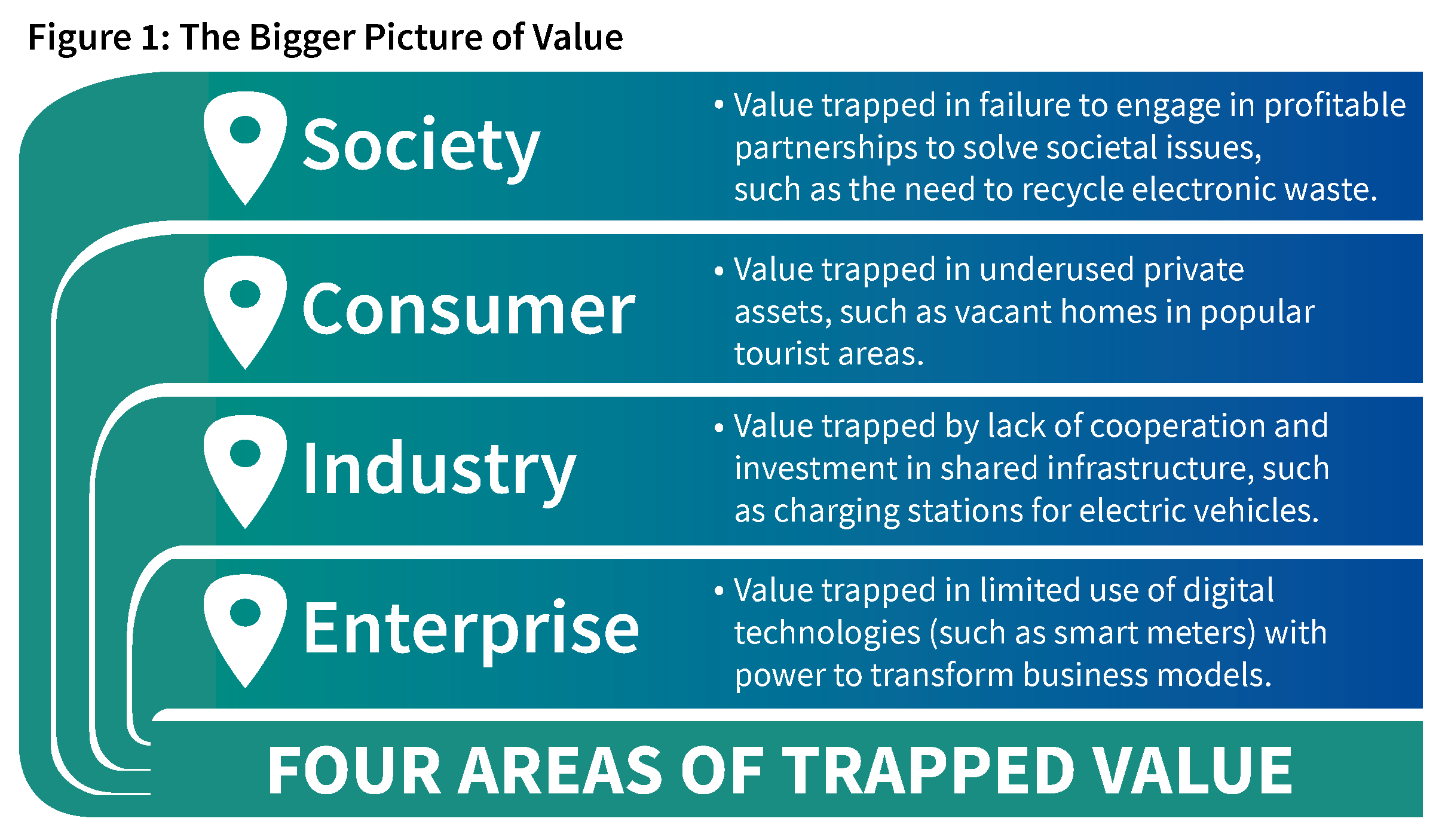

Value is trapped with the consumer when potential demand is latent, say, a desire to save time or to simplify a task. It is also trapped when companies can’t see the potential sources of surplus supply that consumers possess (for example, a vacation home that sits empty, or downtime that a consumer would trade for the chance to make money). And there is an enormous amount of societal value that remains trapped when companies and other entities could, but haven’t, come together in profitable partnerships that benefit constituents beyond their immediate customers and shareholders. (See Figure 1.)

The second reason is counterintuitive: To grow value consistently in the current business environment, many companies are going to need to release much more value for others than they capture for themselves. Many companies are still viewing value creation too narrowly; they see industry profits as a fixed pool. They envision and insist on margins that are unnecessarily high in a world of vastly larger demand and value release. That type of value mindset made sense when companies competed more as single entities going head-to-head against others in an industry. But today, companies are increasingly partners, not simply competitors, and are participants in broad ecosystems, not just traditional industries. It’s “coopetition” in the fullest sense. Even consumers are becoming part of these ecosystems. One way is by acting as “prosumers” – for example by sending electricity back to the grid from their solar panels.

So, if your position is – “This is the value we create and capture for our company today; the market will reward us” – you’ve already lost.

Value Visionaries

The high performers in our study, those that target and create value growth most consistently, think about value differently. They are value visionaries, acutely aware that releasing value has a flywheel effect. This awareness helps them spot opportunities for value creation where others do not – and to convert opportunities into reality where others cannot. UberX, for example, was estimated to have generated $2.9 billion in consumer surplus in its four biggest US markets in 2015 – Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco – equivalent to more than six times its estimated revenues generated in these cities. (For a more comprehensive example, see “Illumina Releases Value Consistently and Broadly”.)

To see just where and how other high performers do this, we need to explore in more detail the four main areas where trapped value resides.

In the enterprise. In any given enterprise, value can be trapped by an over-reliance on traditional business models and capabilities. Value visionaries overcome this challenge by innovating on top of their core capabilities. Tencent, a leading provider of Internet value added services in China, offers an example: the company’s WeChat messaging app, released in 2011, has more than 900 million active users.

But Tencent unlocked a torrent of additional value when it began using its social media services to facilitate mobile payments. The volume of mobile payments in China reached $8.6 trillion in 2016, compared with just $112 billion in America. In the first quarter of 2017, WeChat Pay accounted for 40 percent of the market.

Importantly, releasing trapped value in a legacy business creates investment capacity required to support an incumbent’s innovation efforts in other areas. In fact, our research has found that companies that innovate pervasively – for their legacy businesses and for new ventures – report stronger performance than companies that innovate only selectively in one area or the other.

In the industry. Value is trapped in an industry when only a few companies are reaping rewards in a marketplace where many more could benefit. It also exists when it would take more than one company to deliver an infrastructure improvement that could and would reward many more.

Consider how Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler and Ford joined together to create “Ionity” – a network of over 400 high-power charging stations for electric vehicles across Europe, which will use the Combined Charging System (or CCS) standard. This move is critical to accelerating demand for electric vehicles, in a market that is expected to reach 56 million vehicles in circulation by 2030, 28 times the 2016 stock, even under a low-growth scenario.

For the consumer. Consumer trapped value generally exists where there is latent demand for something that consumers themselves actually own in abundance, and underutilise. Airbnb was founded on the idea that there was latent demand for less expensive and more convenient lodging – and enormous untapped stores of such lodging owned by other consumers who were willing to monetise those assets. It thrives on the consumer value being released for travellers, and for individuals who had vacation homes or apartments sitting empty or who were previously incurring higher costs to attract and secure renters. Airbnb is estimated to have captured $2.5 billion in revenue between 2010 and 2016. But it is estimated to have released $20 billion in host revenue.

Similarly, transportation technology companies have tapped into latent consumer demand for more convenient ways to travel locally. Grab, the leading on-demand transportation and mobile payments platform in Southeast Asia and its highest-valued tech company, has attracted not only freelance drivers but also experienced taxi drivers. In late October 2017, Grab completed one billion rides across Southeast Asia. With over 2.1 million drivers and upwards of 72 million consumer app downloads, we estimate that Grab has helped generate monthly net income of approximately US$2,200 per driver.

For society. Finally, in society at large, trapped value exists where companies have opportunities to partner profitably to create new benefits for the general population. Take reliable access to electricity. Tesla recently partnered with Neoen, a French renewable energy company, and the local government in South Australia, to build and install the world’s largest lithium ion battery plant. The 129-megawatt-hour (MWh) battery is tied to a wind farm run by Neoen; the plant is being used to provide much-needed reliable energy in an area inhabited by 1.7 million people, where power outages and shortages have been the norm. For Tesla, the project was a time-critical proof that it can deliver on its promises, building confidence in its renewable energy capabilities.

Complementary Pursuits

It is a tall order to be more attentive to one’s legacy business and, concurrently, more visionary about other sources of trapped value. Nonetheless, visionary companies improve the way the world lives and works by unleashing new sources of value not only within, but importantly beyond the boundaries of their own enterprise. They know that these are not mutually exclusive pursuits.

Recall the late management guru Peter Drucker’s view: “The proper social responsibility of business is to turn a social problem into economic opportunity and economic benefit, into productive capacity, into human competence, into well-paid jobs, and into wealth. His words rang true when he wrote them; they ring even truer today.”

Illumina’s core business is gene sequencing – genomics. Ten years ago, the cost to sequence a single human genome was $10 million; in 2014, Illumina’s HiSeq X did this for just $1000. And even with about 90 percent market share, Illumina continues to push to release trapped enterprise value: its latest NovaSeq technology is expected to break the $100 barrier.

Meanwhile, the company, which reported global revenues of $2.4 billion in 2016, is also focussed on growing the size of the pie overall, and on staking a claim in the new markets it is helping to create. In 2015, Illumina formed Helix, an initiative dedicated to making DNA-based learning and its benefits more accessible – and hopefully tapping latent consumer demand to have increasingly personalised services and products. For $80, Helix takes a customer’s saliva sample and sequence their DNA, creating an individual profile. These people can then “shop” in Helix’s open marketplace of applications provided by third-party companies. They can use their profile in a variety of ways, for example, to learn more about their genealogy, or acquire a tailored health and fitness regimen. The third-party providers benefit from the release of industry trapped value—as they get access to the portions of data that are relevant to their service in exchange for ceding a share of their revenue to Illumina.

We analysed the growth of current operations (current value) and investor expectations (future value) of 995 of the largest companies by revenues across 14 industries in 12 countries over the period 2000-2016. We calculated a two-year rolling average for both measures (to control for cyclical fluctuations) and then calculated the annual percentage growth for each measure, for each company. We then established an industry benchmark based on the median performance within each of our 14 industries. To establish an indicator of high performance – a “value release premium” – we deducted the industry benchmark from company-level growth. In each year, trapped value release was determined to occur when both future and current value had positive value release premiums. Those that successfully released trapped value for at least 60 percent of the years analysed (equating to two percent of the sample), were classed as “consistent value releasers” (the high performers). For more information please visit: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insight-digital-performance

About the Authors

Omar Abbosh (left) is Accenture’s Chief Strategy Officer. Vedrana Savic (center) is the Managing Director, and Michael Moore (right) is a Senior Principal, with Accenture Research.

Omar Abbosh (left) is Accenture’s Chief Strategy Officer. Vedrana Savic (center) is the Managing Director, and Michael Moore (right) is a Senior Principal, with Accenture Research.

Reference

1. Our research shows that increasing investor expectations (future value) while converting previous growth promises into reality (current value) at a higher rate than industry peers, over a period of time, enables companies to sustain strong roots (profitable core businesses) so that they can weather the unexpected storms brought by disruption in their industry or in the broader market. In parallel, strong roots are needed to fuel growth in new businesses, which is critical to uplifting investor confidence. Relying on only current or future value growth makes companies more vulnerable to disruption.