By JP Kuehlwein and Wolf Schaefer

There are brands that are seen as peerless and priceless. They are able to sustain appeal, a price premium and a disproportionate share of voice and mind – seemingly without significant investment in advertising or promotion. We call such brands “Ueber-Brands” and we call the strategy they use to achieve their iconic status “Brand Elevation”. It’s a strategy we have been researching, modelling, writing about, applying and refining for over two decades now – at least cumulatively.

This article explains why Brand Elevation should be of strategic importance to most brand builders today and summarises the three phases that we have learned are critical in getting a brand closer to that desirable “Ueber-Brand” status. It also provides some case studies and alludes to techniques that are further detailed in our book Brand Elevation – Lessons in Ueber-Branding (Kogan Page 2021).

Brands going “Ueber”

“Ueber” is German for “above and beyond”, and that is where those desirable and iconic brands we are talking about are heading. They are not merely seeking out “consumer needs” or attempting to pre-empt or outdo their competitors at it. Instead, they are guided by ideals, and embrace some of the deep-seated desires humans share: the desire to share a common dream, a mission and myth to believe in; the desire to stand out and be special, but also to be part of a tribe; and the desire for authenticity, for missions that are followed by actions, and dreams that can be believed to come true.

Brands that are able to identify a compelling purpose (beyond making profits) within themselves and that have the skill and discipline to follow it through earn a chance to become iconic; that is, to acquire meaning beyond their material offerings and to be perceived as peerless and priceless by their key stakeholders – to become “Ueber-Brands”.

Positioning is passé

We are witnessing a significant shift in how people approach brands – customers and marketers. Both have become skilled at recognising brands as bundles of functional and emotional attributes advertised to be superior, if not unique, compared to the other. The idea was, of course, to use this branded bundle to “position” a company’s offering at the “top of mind” of people who are ready to consume. But now that many – particularly the educated and members of the leisure class – see right through this scheme, they have shifted their expectations of what brands should be and how they interact with them.

Breakthrough productive solutions still attract, of course. But the rise and quasi-monopolistic dominance of the so-called “FANGs” is noteworthy more for being the exception, rather than a realistic expectation. In fact, it is the endless choice of an Amazon or Alibaba shelf and the cheaper options for popular products that are sure to show up quickly, that make brands turn away to become altogether different and more purposeful propositions.

These brands move from positioning and selling to inspiring and seducing. They leverage that same transparency and accessibility that digitisation has brought, not to aggressively push increasingly similar wares, but rather to declare a mission beyond the material and – importantly – to show proof that they practise what they preach.

And while most readers won’t really need a study by the American Association of Advertising Agencies (2015) to believe that the vast majority of us have become sceptical of commercial pitches for quite a while – including those now-standard CSR messages – the annual “Meaningful Brands” study by Havas Group shows our continued, if not increasing, receptiveness for, and willingness to splurge on, experiential and ethical promises in our eternal quest for meaning. This is fertile ground for growing a purposeful and profitable business, for those who know how to do it (Morrison, 2015) (Thomas, 2020) (Havas Group, 2020).

Brand Elevation

But how can marketers go about “elevating a brand”? Such a position used to be perceived as the preserve of luxury and so-called “lifestyle” brands. But we have found (and documented) that propositions in (almost) any product or service category can become desired beyond compare, be they a make of car, a cheesemonger, a hospitality business, a waste management company or a toilet paper brand.

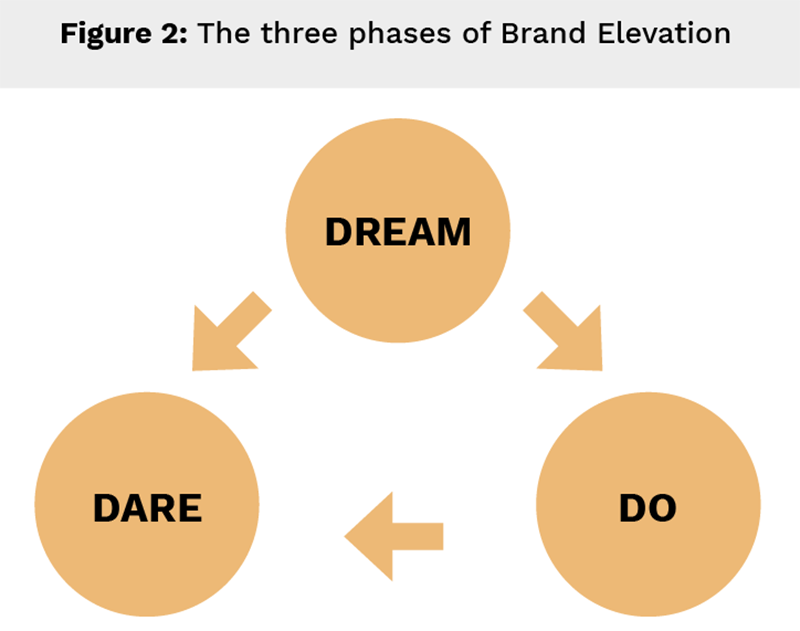

We have identified three critical phases – to Dream, to Do and to Dare – and two essential steps that brand builders need to take in each phase, in order to come closer to that iconic “Ueber-Brand” status (see figure 1). We’ll review and illustrate each of these three phases in the following.

The first step is to look within and define the anchor points for a brand’s existence (its reason for being, beyond doing business – its mission) and the meta-story uniting the truths and dreams that energise its makers and users alike (the brand’s myth).

1. Dream – Find your brand’s mission and elevate your brand story to a myth

Start with yourself

Starting brand strategy development by performing the equivalent of sequencing your own DNA is quite the opposite of what most marketing models teach, and mass-marketers practise, which is to “start with the consumer”, because ‘the consumer is king’ (or queen) and ideas to satisfy their needs better than the competition will yield winning propositions.

Of course, the market and customers still matter. But before getting to opportunistic ideas for people to buy, it is important that a brand uncover the longer-lasting ideals that its key stakeholders buy INTO and are eager to dedicate themselves to. Only then is it time to develop initiative concepts that are coherent with that mission, validate, adjust, find the right targets, ensure profitability, etc.

Remember, “Ueber-Brands” seek to elevate themselves above the fight for the best value, primarily defined by product and price. They seek to be change agents. And for that, they must give us hope for a slightly brighter, better tomorrow, and help us to become who we want to be or to live how we want to live.

Psychologically, they help us define who we are. They are not mere possessions but “extensions of our self”, as Russell Belk defined it (Belk, 1988). Culturally, these brands are useful puzzle pieces that help us complete our personal and shared “cultural projects”, as Grant McCracken calls them (McCracken, 2005). Sociologically, they enable true, resonant dialogues and experiences in the Hartmut Rosa kind of way (Rosa, 2016). And, from an economic and ideological perspective, they help affirm that capitalism and democracy are still the best way, going forward – a belief that the core user target (the educated upper and middle class) desires to be true, given the lack of obvious alternatives.

How do brands achieve this? Take Everlane, Freitag or Patagonia, which sell premium-priced, yet rather basic, clothing and accessories, for example. In a world where there’s too much of everything – including irresponsible sourcing, production and waste, and the damage these cause to our environment – these brands allow people to shift from quantity to quality and from material possession to products and experiences that are made meaningful. Most customers don’t buy a Freitag bag just because it is colourful or convenient. Rather, they buy into Freitag’s ideal of “reimagining and recontextualising” used lorry tarps into bags and wallets, instead of having them pile up in landfills (see also section 2, “Do”, next page).

Does that mean that all Ueber-Brands should have a socioecological mission? Not at all! In fact, most will be better served staying away from missions unrelated or even contrary to their business, as they cannot act in ways that are authentic and sustainable (see the “Do” phase, next page). Just think of the multitude of recent “purpose-driven marketing” fiascos from the Pepsi-Kendall Jenner “Black Lives Matter” disaster (Victor, 2017) to the entire oil industry “being taken to task over ‘greenwash’ ads”, as The Guardian reported (Carrington, 2021). As we explain in our book Rethinking Prestige Branding, reinventing the way people experience your category can be “the little brother of taking on more substantial responsibilities” (Schaefer/Kuehlwein, 2015). Just think how Red Bull, Seedlip, Nespresso or Starbucks have transformed their respective beverage categories. In fact, they have invented new ones just for themselves.

Or consider the case of Airbnb. You could describe the online rental business simply as a platform that matches travellers who seek cheap rooms with homeowners who want to make some extra money. But the brand was able to reframe its proposition and elevate it by distilling what they understood to be a deeper and shared desire that drives both their most loyal hosts and their guests: the desire to connect with people and belong to a place, rather than just to travel to and through. Their mission statement and tagline summarise it well: “We believe in a world where people belong anywhere”, or simply “Belong anywhere”. And that is an ideal and feeling that creates value far beyond the utility of the exchange to those Airbnb disciples (Atkin, 2021).

From story to myth

This second step in developing the dream is to take the tangible – the history, product, organization – and extract the mysterious, the intangible that transcends the everyday and allows a brand to rise to higher ground, to create a brand myth. Just “associating emotions” with your proposition is not enough to lift people to what they want to be. People are bombarded with more messages across more media than at any other time in history, causing mass attention-deficit disorder and disorientation. This means that stories that want to cut through need to be more than just well told. They need to be legendary.

Legends or myths have a reputation for being half-truths, at best, and therefore are often overlooked or rejected outright in the context of business. And yet, anthropologists and historians have shown that our ability to create myths, to believe in them and to use them to unite and progress towards an abstract vision, is what fundamentally distinguishes humans from our fellow creatures and makes us the most powerful of them (Harari, 2015).

Joseph Campbell, probably the most esteemed mythologist of all, called myths “collective dreams”. And myth-making and collective dreaming are what we see hard at work when we step back and observe an Elon Musk, making his latest pronouncements on how “to change the way the world uses energy” (Schaffer, 2015), how to “spread … humanity to other planets” (Mosher, 2018), creating one of the most valuable brands in the world on the way. And myths can work just as potently in a business-to-business context, as Tom Szaky, founder and CEO of waste management company TerraCycle, shows when he rallies captains of the consumer packaged goods industry behind his vision to “eliminate the idea of waste” and enrols them in his various recycling and circular packaging programmes (Kuehlwein, 2019).

2. Do – Bring your mission and myth to life, from the inside out

The biggest challenge in elevating a marque is to be true to that brand mission and myth in everything that is done, not just declared – internally and externally.

Products as ideals manifested

The product or service of an Ueber-Brand isn’t simply about delivering on a performance promise. Prestige products are often mistakenly described as “perfect in every respect”. If that was objectively possible, it would not hurt if they were. And Uber-Brand products can certainly not fall short of the highest general expectations, for example, around safety or, increasingly, sustainability. But what is most important is that the propositions live up to the brand’s mission and myth, and that through all the detail in design, use, ritual and rhyme that can be uniquely associated with them. In today’s social-media-powered world, any discrepancy between a brand’s mission and action is immediately spotted and criticised. So, it is actually a better strategy to be humble, to over-deliver and delight, than to disappoint and be ‘found out’.

Take The Economist. An article by this elevated media brand can be recognised in more than one way: by the choice of serious topics, authoritative reporting, and the very British choice of words, but also by a uniquely spirited, and occasionally mocking, style. In addition, there are the recognisable red brand colour, font, layout, illustrations and … the premium price in a world where most news is expected to be free of charge. And it does not matter whether you encounter The Economist through its “newspaper” (their language), the website or their “Intelligence Unit”. You will recognise the brand as it comes to life.

One of the important product details is the absence of a “byline” that names the author(s) of an article. It is an expression of the organisation’s belief, maintained for some 175 years, that it is the backroom collaboration between its journalists resulting in a coherent and consistent voice of the paper that provides unique value to the readers and society at large (The Economist, 2013). This practice stands in stark contrast to the rest of the news industry today, which seeks to recruit and groom celebrity contributors in the hope of break-out reports and opinion pieces that attract our attention. There is no place for egocentric journalism in The Economist’s world, however.

Living the dream

We are in an experience economy and are still living the ‘digital revolution’, which promises to give brands seemingly endless opportunities to engage with people – beyond the advertising and product on the shelf. But too many of them still resort to the classic “push marketing” approach as they leverage new touchpoints like social media or build out their direct contact via their own websites, stores, events, etc. They push promotion messages that are promised to become more targeted, personalised and (artificially) intelligent, but still and too often strike us as disrupting or dull. On the other hand, companies keep getting publicly shamed by the vigilante of the web for not behaving in line with social norms or – sometimes worse – for not living up to their promises.

This is where brands that start from within and “live out their dream” – their chosen mission and myth – have an inherent and contrasting advantage. Such brands are generally respected for being consistent and transparent and particularly desired by some – their Ueber and strategic targets (see phase 3, below) – who will make the brand’s world part of their own and seek to spread the gospel.

This offers the potential for a happy symbiosis between brand and people, sharing a mission and a dream. And that’s why Ueber-Brands thrive on what we call “ideas and ideals that do”. These “dreams lived” stand in stark contrast to the fashionable declarations of intent that are made by many brands, but which only last as long as the new social or cultural “trends and insights” the agency has based them on are “hot”. Then they puff away, mostly unfulfilled.

Take Ueber-Brand Freitag, mentioned earlier. The Swiss company is visibly living its vision to reimagine discarded lorry tarp into bags and accessories, since 1993 – long before recycling or upcycling was ‘a thing’. And, logically, they are at the forefront of the emerging re-commerce trend, as well, and will likely continue to practise it when the rest of the fashion industry has moved on.

Freitag fans – and there are hundreds of thousands of them by now – can experience this brand living its dream at every imaginable touchpoint: when visiting the offices and factory (on one of their coveted tours), of course through their unique products, in the stores (the flagship is famously made of a stack of recycled shipping containers), on their website (including a section where customers can meet the ‘tarp butchers’), through their blog or their many and repeated initiatives that not only encourage but model how to cycle, recycle, compost and do other things that limit our carbon footprint. And Freitag is clearly willing to put its effort and money where its mouth is. From the symbolic gestures, like free bike rentals at some of its locations, to the substantial, such as paying its workers (Swiss) living wages while offering an eternally life-extending product repair service that would be regarded as loss-making, if not destructive to the business, by the average accessory maker (Kuehlwein, 2016).

3. Dare – Identify muse and disciples and inspire them to spread the gospel

Daring is the way in which Ueber-Brands interact with the world. They are courageous and confident leaders, inspired by and inspiring its targets – above all, the influential super-fans we call the “Ueber-Target”.

Beware of using big data and digital marketing as a blunt tool

With the advent of social media, robot-enabled customisation and all the other ever-accelerating tech innovations in connectivity, manufacturing or fulfilment, the marketing world was abuzz with talk about the exciting opportunities of “co-creation”, “brand communities”, “user-generated content”, “influencer endorsements”, and so forth… until marketers discovered that working with all those media platforms, content creators and influencers was not only complex, but also very expensive, while far from sure-fire effective.

A key driver of cost and ineffectiveness is that most of the brand messages are “manufactured” – quite literally, that they disappear in a sea of similar such messages posted by similar influencers about similar products by competition on the same or similar social media platforms, and are perceived as altogether inauthentic by much of the target audience. To a large extent, it feels like good old advertising has simply expanded to new channels in the form of 5-second clips or 280-character tweets.

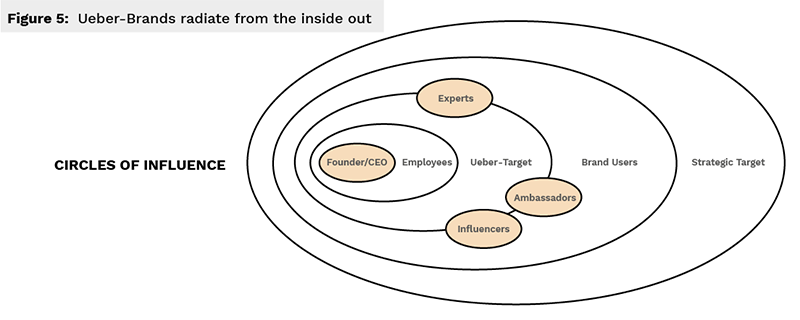

Instead: “Cherchez la Ueber-Target” …

A brand’s Ueber-Target is its muse. It inspires the development of the brand’s products and manifestations. That’s why we refer to them as a “design target”. But this group – and sometimes it can be focused on one founder or a few people – is not just the brand’s source of inspiration internally. Importantly, it also represents a group of people who are in love with the brand and burn to pass their knowledge and passion for it on to the outside. They help the brand “radiate from the inside out”, as we like to say.

In contrast to “professional influencers”, the Ueber-Target will often readily spread the gospel without getting paid – at least in cold cash. Rather than paying bribes, Ueber-Brands will seduce and feed their Ueber-Target with the innovations they inspired, the limited-edition collaborations with partners they admire, the connoisseur talk and rituals they dig.

… and create a virtuous bonfire

If it is done well, the Ueber-Target will duly pay back the special attention bestowed on them by raving and boasting about the brand – and that among friends and fans which are quite likely to share their tastes and desires and extend the circle of active followers. We call that larger circle the “Strategic Target”. In being the idols or early adopters who are nevertheless in close contact with their followers, the Ueber-Target helps the brand balance distance and proximity, longing and belonging, which so essential for Ueber-Brands. They are crucial in making your brand identities approachable by reaching out, yet they also keep it aspirational with their exclusive access to products and knowledge; they are fully part of the dream, while the followers at large can only keep dreaming about it.

This is also the place where leveraging data and choosing and investing in the right social media platforms comes in, and where they can become exponentially powerful tools. You use them to identify the Ueber-Target and replicate them in Strategic Target profiles, and then seed or promote the most influential conversations. The objective is to create a virtuous cycle, with fans feeding high-potential future fans, while also feeding back new ideas to the brand. It’s an ecosystem – some talk about brand community and movement – with the brand remaining at the centre (or at last a central tool). It’s priceless in a world craving transparency, collaboration and authenticity.

The Ueber online-gaming brand Fortnite illustrates just how strong – and valuable – the urge to belong can be and the important role the Ueber-Target plays in this value creation. In its basic version, Fortnite can be played for free. Nevertheless, it generated over $9 billion in sales in 2019 to 2020 (Clark, 2021). How is that? Many players invest heavily in virtual accessories, like the latest “skins” (avatars) or celebratory rituals and dances known as “emotes”, to be recognised as part of the Fortnite tribe of regular players. They are inspired by and seek to emulate the “pros”, a league of the most seasoned, creative or popular players who can show off unique skills, moves and vintage accessories that are no longer available.

Fortnite works with this venerated group and the close-knit cycle of online pop icons around them, like gamer-musician Marshmello or rapper Travis Scott, as well as media franchises and brands that their Strategic Target craves, in order to develop their accessories, rituals and events. For example, a series of games by Tyler “Ninja” Blevins against rapper Drake famously attracted tens of millions of watchers, and a limited-edition skin collaboration with Fortnite that followed caused a general frenzy, selling out in no time. Everyone wants to get into the skin of their heroes – quite literally – and belong, even if most of them know that their longing to be admitted to the Valhalla of Fortnite will not be fulfilled. It’s that tension, the “who is in and who is out”, that keeps the game going and an Ueber-Brand desirable.

Last, but absolutely not least: style

And, as if all of that bringing mission and myth to life and the balancing of longing and belonging were not already hard enough, Ueber-Brands also need to pay particular attention to how they execute their style, attitude and tone. Because, when it comes to prestige, the modern kind as well as the old, style matters just as much as substance. As with any human being who exudes sophistication or an “otherworldly” charm, it’s also this “how” that sets the Ueber-Brand apart and above more immediately than any “what” – meaning strategic choices and actions – ever could.

Besides, style gives them room and bandwidth to continuously oscillate, mesmerise and surprise. The mission and myth, while being the true north, must be retold and creatively transformed and evolved again and again in myriad ways for an Ueber-Brand not to become a bore. Ueber-Brands are such because they enjoy cultural resonance and significance beyond their commercial or category clout. And that is an ongoing exercise in style.

Above all else, Ueber-Brands are change agents. Their job is to inspire and guide us; that’s what makes them ‘Ueber’, above and beyond others. They must give us hope for a slightly brighter, better tomorrow. They must show us who and how we want to be, live how we want to live. And they must guide us there in ever more intriguing and exciting ways. In short, they must Dream, Do and Dare.

Brand Elevation Cliffs Notes

Dream

1. Set a Mission – Starting with understanding themselves, then checking how this fits with the world around them.

2. Write a Brand Myth – Uniting facts and imagination for stories that take the brand and its fans higher.

Do

3. Realise the Dream – Creating and celebrating products and services as ideals manifested.

4. Live the Dream – Building an organisation brand presence that radiates inside out and outside in.

Dare

6. Find the Ueber-Target – Defining the muse and designing the target in order to inspire and harness them to share the gospel.

7. Ignite All Targets – Integrating all stakeholders and partners to jointly make your Ueber-Brand succeed and create a movement.

About the Authors

JP Kuehlwein is co-founder and CEO at Ueber-Brands consulting in New York City. He is also Adjunct Professor of Marketing at NYU Stern and at Columbia Business School and the leader of the Marketing Institute at The Conference Board. Previously, he was Executive Vice President at Frederic Fekkai & Co., as well as Brand Director and Global Director of Corporate Strategy at Procter & Gamble.

Wolf Schaefer is CEO and founder of zwoelf consulting, specialised in narrative brand strategies. Based in Berlin and New York City, he is Guest Professor at the XU Exponential University, Potsdam. For the past 25 years as chief strategist he has worked with many of the world’s top marketers at LVMH, P&G, Miele, Swarovski, Coty and Unilever, et al.

Together, they are authors of the book Rethinking Prestige Branding (Kogan Page, 2015), which analyses the principles that drive the success of premium brands, and Brand Elevation (Kogan Page, 2021), a handbook on how to create them.

References

- Atkin, D., 2021.”The importance of culture, or: How Airbnb found, launched and lives its purpose”. In Schaefer, W. / Kuehlwein, JP, 2021. Brand Elevation – Lessons in Ueber-Branding. London: Kogan Page.

- Belk, R.W., 1988. “Possessions and the Extended Self”. Journal of Consumer Research, 1 September p. 139–168.

- Carrington, D., 2021. “A great deception: oil giants taken to task over ‘greenwash’ ads”. The Guardian, 19 April.

- Clark, M., 2021. “Fortnite made more than $9 billion in revenue in its first two years”. The Verge, 3 May.

- Harari, Y., 2015. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. New York: Harper.

- Havas Group, 2020. Meaningful Brands Study, s.l.: Havas Group and Vivendi.

- Kuehlwein, J., 2016. “A Freitag Visit – Manufacturing as Manifestation of Mission”. Ueberbrands.com, 26 October.

- Kuehlwein, J., 2019. “TerraCycle: How To Brand Waste – Tom Szaky, CEO and Co-Founder explains”. Ueberbrands.com, 3 June.

- McCracken, G., 2005. Culture and Consumption II: Markets, Meaning and Brand Management. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Morrison, M., 2015. “No one trusts advertising or media (except Fox News)”. AdAge Online, 24 April.

- Mosher, D., 2018. “Elon Musk explains why he launched a car toward Mars – and the reasons are much bigger than his ego”. s.l.:s.n.

- Rosa, H., 2016. Resonanz: Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Schaefer, W., Kuehhlwein, JP, 2015. Rethinking Prestige Branding – Secrets of the Ueber-Brands. London: Kogan Page.

- Schaefer, W., Kuehlwein, JP, 2021. Brand Elevation – Lessons in Ueber-Branding. London: Kogan Page.

- Schaffer, A., 2015. Tech’s Enduring Great-Man Myth. MIT Technology Review, 4 August.

- The Economist, 2017. “Why are the The Economist’s writers anonymous?”. Medium.Economis.com, March 27.

- Thomas, S.K.S., 2020. “Consumer skepticism towards cause related marketing: exploring the consumer tendency to question from emerging market perspective”. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 18 January p. 225–236.

- Victor, D., 2017. “Pepsi Pulls Ad Accused of Trivializing Black Lives Matter”. The New York Times, 5 April.