By Maria Guadalupe, Julie Wulf & Hongyi Li

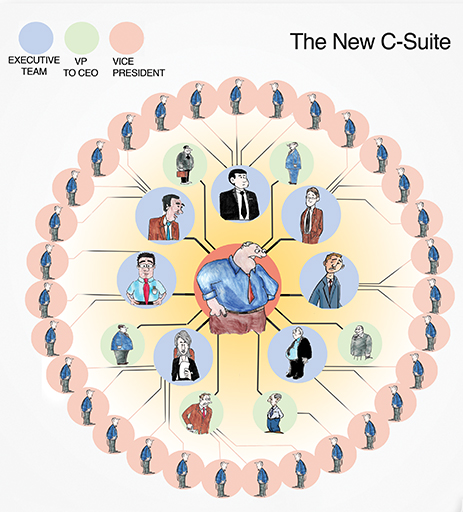

Research shows that the recent transformation in the C-suite, that is, the skyrocketing number of executive team of chief officers or Senior VPs that report directly to the CEO, shifts decision making power up, not down.

In the past three decades there has been a lot of talk, particularly in the popular business press, about the delayering of corporations and the flattening of the corporate hierarchy, with middle management being the victims. In fact, research on corporate flattening does show that CEOs have eliminated layers in management ranks; they have also broadened their spans of control, and changed pay structures by increasing the use of incentives – moves that suggest decision making has been delegated to lower levels of management.1 Yet, amidst the hue and cry about the flattening of the corporation and the death knell of middle management, another, less heralded, transformation has been occurring–and in the area that matters most: the C-suite, the executive team of chief officers or Senior VPs that report directly to the CEO. These are the executives that chart a firm’s course, coordinate activities, and allocate resources across business units–all activities that are critical to a firm’s performance. In the past two decades, their numbers have skyrocketed. Even as layers of management have been blasted, like rock walls, from the middle, the layer of direct reports to the CEO has been fortified. So, while it is certainly true that flattening, i.e. the elimination of middle management layers, has pushed some decision making down to the frontlines and given companies greater ability to respond to customers, our research shows that the addition of senior executives to the C-suite shifts decision making power up, not down.

According to our recent survey, the number of managers reporting directly to the CEO has doubled, from an average of five direct reports in 1986 to an average of 10 today. Using a unique panel dataset rich in details of managerial job description, reporting relationships and compensation structures for senior management positions in 300 Fortune 500 companies from over two decades (1986 to 2006) our research uncovered more details.2 Indeed, more than this boom in the CEO’s direct reports, it revealed that a marked increase in functional managers (e.g., finance, human resources, marketing) is filling the C-suite rather than an increase in general managers, usually heads of business units. The shift was dramatic. Of the five positions added to the CEO’s span of control, on average over the 20-year period of our research, four were corporate staff (functional managers) and only one was a line or general manager (e.g., division manager). Just to clarify, functional managers are responsible for corporate-wide activities of their specialized function (e.g., finance, legal, marketing, R&D). In contrast, general managers, also called line managers, are concerned with a broad range of functional activities within their business units and typically have profit and loss responsibility.3

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

We can learn a lot about organizations and what is happening to them not only by examining the drivers behind this compositional change in the C-suite, but also by considering the implications these changes have for CEOs, their direct reports, and management at all levels of the organization.

Coordinating at the Core

We call the trend towards an increase in functional managers at the top “functional centralization,” and to explain its prevalence we consider two important trends in the global business environment over the past two decades of our research: a narrowing of firm focus and a marked increase in IT investment. As a response to these trends, the classic “synergy” explanation would suggest that as a firm narrows its business portfolio, it increases opportunities for synergies, and, as it increases IT investments–from more PCs to expanded office local area networks (LANs)–the cost of communicating, and hence, the cost of exploiting synergies, goes down.

Our research is actually at odds with a simplistic application of “synergies” as a catch-all explanation. We find that firms do not simply increase functional managers as they narrow firm scope and make major IT investments. Instead, we find very different responses to changes in firm focus versus changes in IT investments by different types of functional positions, and in particular between product functions and administrative functions: product or front-end functions are those, like marketing and R&D, that are closer to both customers and product markets and which require information that is product-specific, while administrative or back-end functions are those areas, such as finance, legal counsel, and human resources, where information requirements vary less across divisions, products or brands.4 We find that as firms become more focused, they increase product functional managers with no effect on administrative functional managers. Similarly, we find that the number of administrative functional managers increases with IT-intensity. However, IT investment has no effect on upping the number of product functional managers in the C-suite.5

As we discuss in the paper, this surprising finding actually makes sense when you consider that different types of functional managers on the executive team perform activities that vary in terms of the information they use. A product manager, the chief marketing officer, for instance, uses information that is product-specific and more difficult to aggregate across businesses. In contrast, an administrative functional manager, such as a CFO, uses information that is easier to aggregate, because it has a similar format across all products.

Firm Focus and the Functional Manager

Over the past several decades, deregulation and increased trade have spurred product-market competition in the globalized marketplace. Replacing the corporate raiders and hostile takeovers of the 1980s are large institutional shareholders, who are the new sources of external governance. Declining costs of and massive investment in information technology have created opportunities for more efficient organizational forms. In response to these massive shifts in their environment, firms have spun off their peripheral businesses, focused on core areas and outsourced selected activities. Mergers have been at an all time high.6

Traditionally, firms have placed functional managers in their executive teams in order to centralize decisions related to their function, to coordinate activities across business units, and to involve the function in strategic decision making with the CEO7 – all of which are broadly related to the objective of coordinating activities, realizing synergies and improving efficiency.

In determining the composition of the C-Suite, there is a tradeoff between the firm assigning activities to functional managers to coordinate corporate-wide functions and exploit–yes–synergies (e.g., Chief Marketing Officer and marketing activities) versus assigning activities to general managers responsible for business units – managers who may have better local information and incentives, such as P&L (profit and loss) responsibility. As a firm focuses on its core areas, divests peripheral businesses, and increases business relatedness, the differences between product functions (such as marketing) across the various divisions of the firm become less pronounced. This increases the synergies that can potentially be exploited by product functional managers, making them more valuable relative to general managers.

Two companies, IBM and Unilever–a tech and consumer products giant, respectively–exemplify this shift towards product functional managers and show what functional centralization looks like in practice. Before Lou Gerstner was hired as CEO in 1993, IBM was a highly decentralized organization operating in related info tech businesses, but with little coordination across them. The organizational chart would have shown an executive team comprised primarily of autonomous general managers of business units (e.g., mainframes) and very few functional managers. When Gerstner joined, he deliberately “centralized” activities to turn around the firm’s massive losses, which he later attributed to the “balkanized IBM of the early 1990s.”8 Not long into his tenure, Gerstner dramatically changed the firm’s strategy to one based on an integrated product and service offering to customers (“One IBM”). Since the new strategy required extensive coordination across business units, Gerstner shuffled his C-suite and added functional managers to facilitate corporate-wide coordination (see Figure 1). For example, he created a Chief Marketing Officer position (CMO) and filled it with an external hire. Historically, all marketing activities were performed within the individual business units, which led to 100 marketing campaigns overseen by various advertising agencies.9 To better coordinate marketing activities across all business and unify global brand, the new CMO consolidated all of IBM’s buying, planning and direct marketing in the hands of one ad agency. Gerstner’s centralization strategy, highlighted by the addition of functional managers to the C-suite, enabled organization-wide coordination.

In 2004 Anglo-Dutch consumer products behemoth Unilever underwent a radical restructuring, also called “One Unilever,” which united dozens of companies under one standardized operation. In the reorganization, started by then-CEO Patrick Cescau, Unilever shed underperforming brands, sold its frozen foods business and trimmed operations by cutting 49,000 jobs. Like IBM, Unilever also pushed functional managers into the C-suite, most notably now-retired CMO Simon Clift, who was a passionate advocate for creating a global strategy for each brand, thereby centralizing marketing direction for over 150 countries. As Clift told Marketing Week in 2009, there has to be a “trade-off between leveraging the scale of Unilever and ensuring the [marketing] strategy is attuned to local consumers. Because what will certainly happen if it’s left to every country is we will have 150 different versions.” Centralizing marketing for Unilever, he asserted, would ensure that the best ideas could thrive, regardless of where they were developed.10

IT Investment Propels Admin Managers

Reaping the returns to coordination also occurs as organizations take advantage of the other trend mentioned–increases in IT investment. The Internet came of age over the decades of our research. To define the IT-intensity of a firm, we looked at the number of PCs per employee. Since our data on IT-intensity covers the 1986-1999 period, this variable is particularly meaningful, since this is the time when computer prices were falling, dot-com companies were booming and firms started adopting an array of new technologies.11 Other variables that contributed to IT-intensity, and which accompanied hardware purchases, were software like Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) suites, technologies that improve communication, such as Intranets, and Local Area Network nodes–all of which enabled direct exchange of information and enhanced communication.

Why would the growth in the rise of IT investment be correlated with the rise in administrative functional managers in the C-suite? One explanation is that before the onset of email and intranets, etc., it would have been too expensive for employees to communicate crucial local information from the front lines to the C-suite. More than for product function operations, IT makes it easier for administrative functional managers to codify and aggregate information; for example no matter what product or division is being discussed, a P&L spreadsheet has the same format, so financial information is more easily aggregated across products and divisions when improvements in IT enable and enhance the use of spreadsheets. Consequently, IT-intensity pushes Legal Counsels, HR directors and Chief Financial Officers to the forefront. In a 2011 Accenture study, executives who led shared services organizations–organizations designed to reduce overhead costs by consolidating administrative or support functions in areas such as finance, human resources and IT, were “increasingly accountable to the corporate C-suite.” While 59% of the executives polled report to C-suite level officers, with 17% reporting directly to the CEO, only 8% reported to the CEO two years ago, according to a similar survey in 2009.12

Reinforcing the connection between IT-intensity and the increasing presence of HR chiefs in the C-suite, the results of a Boulder, Colorado-based Human Resources Services, Inc. survey showed that HR executives were playing an important strategic role within the company–shifting “from human resources to strategic resources.” The survey attributes part of that shift to the use of sophisticated analytics by HR executives. Among what the survey calls “more advanced companies” (MAC), those 17% reporting higher integration of HR within the company leadership, 88% reported that HR heads meet with the CEO to ensure alignment of the HR strategic plan with the corporate strategic plan, and 88% of MAC firms reported having a database or other ways to track such things as planned retirement of company leaders to ensure an orderly succession process.13

The Proof is in the Pay

Of course, the real proof of the rise in importance of functional managers is where you would expect to find it: their compensation. First of all, we find that simply by joining the C-suite and reporting directly to the CEO, a senior manager can expect an 11% increase in base compensation and a 15% increase in total compensation. This squares with the increase in the manager’s authority and level of responsibility. Yet even more interesting than a general pay increase for those taking on the often daunting coordinating responsibilities in the C-suite is a central finding of our research: general (or division) manager pay decreases as more functional managers move into the C-suite, reporting directly to the CEO. Further, the increase in the number of product functional managers is strongly associated with a decrease in division manager’s pay–one more product functional manager reporting to the CEO is associated with a 2.4 % lower salary and 5.4% lower total compensation for division managers. In contrast, we find no correlation between administrative functional managers and division manager pay.14 These changes can be explained by the fact that product and administrative functional managers in the C-suite differ in the types of activities they perform. Product functional managers are involved in the coordination of activities across business units to generate revenue. In contrast, administrative functional managers are more involved in the monitoring or auditing of functions across business units to ensure compliance with corporate policies.

Implications

While reconfiguring the C-suite affects managers at all levels, it is easiest to see the significance of our research for CEOs, who can align their human capital with firm strategy and their level of IT-intensity. It is clear that CEOs need to design the structure of their top management team (TMT) based on firm scope and the opportunities for synergies, while recognizing the distinction between different types of functions and the importance of the nature of the information that is required to perform different activities. For instance, the CEO who is narrowing firm focus divesting tired brands would do well to centralize product functional activities by putting product-functional managers in the C-suite. If the company has made a major investment in IT, the slate of direct reports in the C-suite should include HR, IT, Finance and other admin-functional managers, in order to communicate more efficiently across these areas.

Whatever the balance of product-functional and admin-functional managers on the C-suite, the CEO with more functional manager direct reports will have more knowledge or, if not, involvement in functional areas. These CEOs are likely to be more hands-on, taking on a wider array of responsibilities as they strive to understand every facet of the business not to mention all the new technologies they are adopting.15

Alan Mulally, the mastermind behind Ford Motor Company’s dramatic turnaround between 2006 and 2010 exemplifies the all-knowing, all-seeing CEO. This is in contrast to the lone leader operating out of the tip of the old corporate pyramid, buffered from functional areas by a Corporate Operations Officer (COO), now also becoming a casualty of corporate flattening.16 Mulally had decided to focus on the Ford brand and produce a much narrower range of autos built on a few core platforms; in addition, the company divested its entire Premier Automotive Group.17 A key tactical feature of the turnaround was the weekly Thursday meeting in Ford’s Thunderbird room where Mulally met with his 18 direct reports. After presentations from the leaders of Ford’s four profit centers, Mulally called up leaders of the 12 functional areas – from product development and manufacturing to HR and government relations. “When I arrived there were six or seven people reporting to Bill Ford, and the IT person wasn’t there, the human resources person wasn’t there,” Mulally told a Fortune reporter, “so I moved up and included every functional discipline on my team because everybody in this place had to be involved and had to know everything.” While the meeting only happened once a week, the walls of two adjacent rooms were lined with 280 performance charts, arranged by area of responsibility, with an actual large photo of the executive in charge. All the direct reports commanded wall space and by constantly perusing the ever-changing charts and data, Mulally may not have had his finger in every pie, but he had his eye on every pie chart.18 The same could be said of the late Steve Jobs at Apple, who took pride in the company’s many formal meetings, including the Monday meeting of the C-suite team, again filled with functional heads, such as industrial design, marketing and hardware engineering.19 According to Adam Lashinsky of Fortune, Jobs often contrasted Apple’s approach with competitor Sony, saying the latter had too many divisions to create the iPod whereas Apple has functions.20

Not every CEO is an ultra-involved Mulally or Jobs, however. One can also find companies for which a broader span of direct reports, particularly in functional areas in which the CEO does not have direct experience, leads to more delegation to those C-suite members. After recognizing that his own tendencies towards micromanagement drove away the most qualified functional managers, Cristóbal Conde, former CEO of SunGard, a software and IT services company, said he tried a different approach, “…the trick is to get truly world-class people working directly for you so you don’t have to spend a lot of time managing them. I think there’s very little value I can add to my direct reports. So I try to spend time with people two and three levels below because I think I can add value to them.”21 Conde felt his time would be better spent helping manage and develop the talent at the lower levels than of the C-suite managers who were at the top of their game already.

Planned formal C-suite meetings, “double-hatting”– giving functional managers general manager responsibilities and vice versa–all of the daily or weekly tactics that accompany the rise of functional managers in the C-suite. But what about the long view? Our results raise questions that only further research can answer:

• What are other changes in the firms’ competitive environment that might explain the dramatic shift to the importance of functional managers, but which are unrelated to exploiting synergies? For instance, firms may face more complex problems over time that require specialized knowledge within the firm and especially from members of the executive team.

• How can firms balance the centralization of activities that pushes decision-making to the functional managers at the top and decentralization of decision making that, in flattened corporations, gives more authority to lower level and even front-line managers (often in an attempt to be closer to the customer)? Is there a contradiction here? For instance, Apple is described as operating with a “command-and-control structure where ideas are shared at the top–if not below.”22 Will that structure ultimately add value or detract?

• Perhaps the most important question is how we train and develop those who will sit in the C-suite in the future? Current MBA programs are designed to produce generalists, not specialists, and the new proliferation of Executive MBA programs (EMBA) are developing mainly general management skills. If, as our results show, functional managers are being rewarded both with a seat at the CEO’s table and with higher compensation, how can we train those who will be understandably eager to take their places?

Finally, the takeaway from this look at the trend of functional centralization should not prompt a one-size-fits-all move to bump functional managers into the C-suite. We cannot emphasize enough that the composition of the C-suite reflects the wideness or narrowness of a firm’s focus and the level of intensity of its IT investments and also the specific environment in which the company is operating. The savvy CEO will take the changes afoot in the C-suite into account and consider the functions that can best advance company strategy, add value and increase productivity.

*The authors would like to thank Nancy J. Brandwein for writing and research assistance.

About the authors

Maria Guadalupe is an Associate Professor at Columbia Business School. Her research has been published in leading journals and explores the changes in the internal organization and corporate governance of firms resulting from increasing competition and globalization. She teaches courses on incentive and organizational design, as well as on the Brazilian economy.

Julie Wulf an Associate Professor at Harvard Business School whose research addresses internal governance choices of senior management in large U.S. firms, has published in both academic and management journals. A Co-Editor of The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, she teaches MBA and executive courses on corporate strategy and internal governance.

Hongyi Li is a Postdoctoral Associate at the MIT Sloan School of Management. His current research focuses on the economics of coordination and communication in organizations.

References

1.Wulf, Julie, “The Flattened Firm – Not as Advertised,” Harvard Business School Working Paper , March 2012

2.The data used in this research includes a panel of around 300 Fortune 500 firms between 1986 and 1999. In addition we obtained data for 50 of those firms for 2006.

3.Guadalupe, Maria and Hongyi Li and Julie Wulf, “Who Lives in the C-Suite? Organizational Structure and the Division of Labor in Top Management,”(2012) NBER Working Paper No. 17846

4.In the strategy literature, Porter (1985) distinguishes between two types of activities within functions: support (finance, HR, systems) and primary (manufacturing, inbound and outbound logistics, sales, after-sales support). See Porter, Michael A., The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Free Press, New York, 1985.

5.Ibid

6.Wulf, Julie, “The Flattened Firm – Not as Advertised.”

7.Finkelstein, Sydney, Donald C. Hambrick and Albert A. Cannella Jr. (2009). “To Management Teams,” in Strategic Leadership: Theory and Research on Executives, Top Management Teams, and Boards, New York; Oxford University press, pp. 121-63. See also Menz, Markus, “Functinoal Top Management Team Members: A Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda,” Journal of Management, January 2012 (38) 1: pp. 45-80.

8.Gerstner, Louis, Jr., Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance, Harper Collins, New York, p. 77, 2002

9.International Business Machine (IBM), 1994 Annual Report, p.6.

10.Jack, Louise, “PROFILE: The soaps, the glory and the universal truths in marketing,” Marketing Week, April 23, 2009, pp. 20-24.

11.Dunn, Timothy and et al (2004). “Wage and Productivity Dispersion in U.S. Manufacturing: The Role of Computer Investment,” Journal of Labor Economics, 22 (2): 397-430.

12.“Information Technology; Accenture Study Finds Shared Services Executives Accelerate C-Suite Visibility; Get closer to Customer to Deliver End-to-End Services,” Information Technology Newsweekly, Oct. 11, 2011, p. 76.

13.Anonymous, “Survey Finds Major Companies Using HR to Address Broad Goals,” HR Focus, Feb 2012. (89)2: p. 14.

14.Guadalupe, Maria and Hongyi Li and Julie Wulf, “Who Lives in the C-Suite? Organizational Structure and the Division of Labor in Top Management,”(2012)

15.Bandiera, Oriana and Andrea Prat Raffaella Sadun, and Julie Wulf, “Span of Control and Span of Activity”(2012) Working Paper.

16.Wulf, Julie, “The Flattened Firm – Not as Advertised,”

17.http://www.strategy-business.com/article/11207?gko=d3a9c

18.Taylor III, Alex, “Fixing Up Ford,” Fortune, May 25, 2009 (159)11, pp. TK.

19.Isaacson, Steve Jobs, Simon & Schuster, New York, p. 362, 2011.

20.Lashinsky, Adam, “Inside Apple,” Fortune, May 23, 2011 (163)7, pp. 125 – 134.

21.“Structure? The Flatter, the Better” [an interview with Cristóbal Conde], The New York Times, Jan 17, 2010, BU2.

22.Op.Cit.

[/ms-protect-content]