By Philipp Siemeister, Supervision by Dr. Anna Rostomyan

Introduction

Generation Z is the next generation to enter the labor market. It includes all people born between 1995 and 2010 (Mann, 2022). This new generation brings new demands and expectations of employers, their so-called work values (Dose, 1997). Work values describe the aspects of work that are relevant to job satisfaction (Elizur, 1984 and Ros et al., 1999 cited in Moniarou-Papaconstantinou & Triantafyllou, 2015). The regulation of emotions is a fundamental part of adapting to different situations and dealing with them (Schutte & Malouf, 2013, Bridges et al., 2004). These situations include the world of work; emotional skills are one of the most important resources in relation to work (Jordan et al., 2007). Studies have shown that Emotion regulation and job satisfaction are linked with eachother (Pimentel & Pereira, 2022; Madrid et al. 2020; Luque-Reca et al. 2022). However, since work values and thus job satisfaction of Generation Z differ from other generations (Siemeister, 2024), it is relevant to examine this connection in such a sample. Additionally, there was no study found examining this topic in a Generation Z sample. In this article, the potential connection between emotion regulation and job satisfaction in Generation Z is analyzed with a quantitative study.

Job satisfaction

There are many definitions of the construct in the literature, but it can be described as: “[…] an attitude and then includes the emotional response to work, opinion about work, and willingness to behave in certain ways at work.” (Six & Felfe, 2004 cited in Nerdinger et al., 2019).

Job satisfaction is comprised differently in Generation Z than in other Generations. Members show different work values, which are the aspects of work that are important for job satisfaction. These are not represented in existing measurements of job satisfaction. The differences mainly lie in the factors of leadership, working conditions and development opportunities (Siemeister, 2024; Elizur, 1984 and Ros et al., 1999 cited in Moniarou-Papaconstantinou & Triantafyllou, 2015).

Emotions and emotion regulation

The term “emotions” does not have one set definition in the literature, however multiple authors agree that “it is a complex phenomenon that is accompanied by a change in various components” (Puca, 2021). These components are physiological reactions such as an increased heart rate, a behavioral component in the form of e.g. facial expressions and an experiential component, which describes how a person experiences emotions (Puca, 2021).

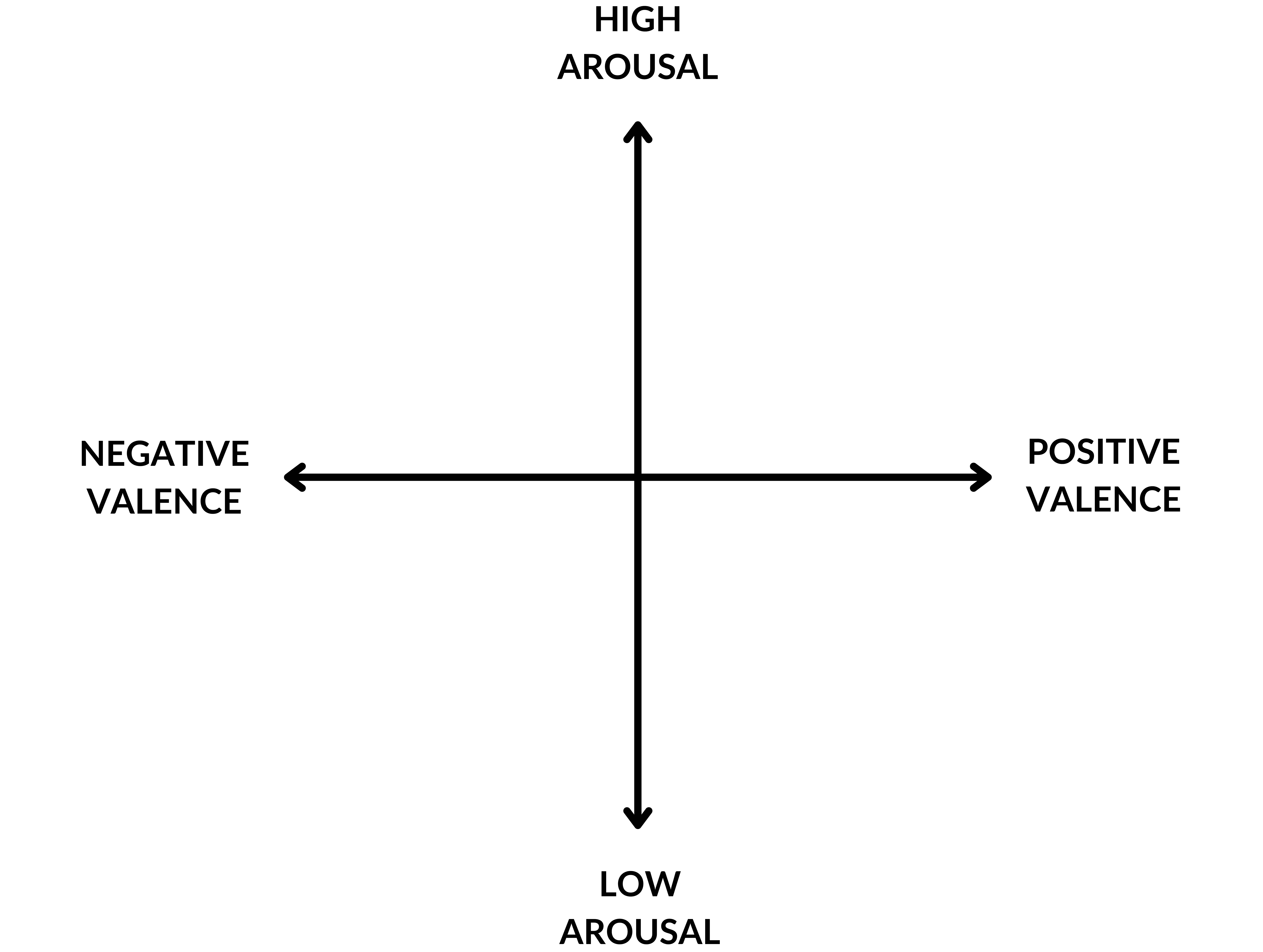

How emotions are classified differs depending on the author and there are multiple different approaches in the literature (Bulgang et al., 2020). A common approach is the valence-arousal plane by Russel (1980), which is shown simplified in figure 1. “Valence” describes a classification from positive to negative whilst “arousal” describes a classification from low to high arousal. Different emotions can be categorized in the four quadrants according to their relation of valance and arousal.

Figure 1: Depiction of the valence-arousal plane, creation of the author (adapted from Bulgang et al., 2020)

Emotions and their regulation are fundamental for individuals to adapt to different areas of life (Schutte & Malouff, 2013) and emotional skills constitute one of the most important personal resources for work (Jordan et al., 2007). Emotion regulation itself is defined as physiological, cognitive and behavioral processes which enable the individual to shape the experience and expression of their positive and negative emotions (Bridges et al., 2004).

Relationship between emotion regulation and job satisfaction

There are multiple different studies investigating the relationship between emotion regulation and job satisfaction in different scenarios. Pimentel & Pereira (2022) focused on the differences in the relationship of these constructs between family and non-family firms. Their results showed a strong and positive relationship between emotion regulation levels and reported job satisfaction (r=0.508; p=0.001). Madrid et al. (2020) found mediation effects between affect improving and affect worsening emotion regulation, positive and respectively negative affect and job satisfaction levels. The effects were of medium size and direct effects of emotion regulation on job satisfaction were not significant. Similar results can be found in Luque-Reca et al. (2022). Their paper found a small positive correlation between the constructs (r=0.26, p<0.01) but could not establish a direct and significant effect between emotion regulation and job satisfaction. However, they also found significant mediating effects between emotion regulation, positive and negative affect and job satisfaction of medium size. Yet, there is no study investigating the relation between these constructs in Generation Z. Examining the latter is the aim of this study.

Research question and hypotheses

The research question for this study was set as: “How are emotion regulation and job satisfaction related in a Generation Z sample?”.

Based on the existing literature two Hypotheses were formulated. H1 stated: “There is a significant and positive correlation between emotion regulation and job satisfaction in a Generation Z sample.” H2 stated: “Emotion regulation is a significant predictor of job satisfaction in a Generation Z sample.”.

Methodology

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between emotion regulation and job satisfaction in a Generation Z sample.

To achieve this, a questionnaire was designed in the tool “Unipark” which implemented two scales. The first scale was the brief version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale DERS-16 (Bjureberg et al., 2015). This was beforehand translated into German using the translation of the DERS by Gutzweiler & In-Albon (2019). The DERS-16 uses a 5-point Likert scale. It was recoded, so that higher values indicate lower difficulty in the regulation of emotions, respectively better emotion regulation. The questionnaire has 16 Items and the five subscales: Clarity, Goals, Impulse, Strategies and Nonacceptance. The second used scale was the FAGZ (Siemeister, 2024) which is a scale for measuring job satisfaction tailored to Generation Z. This questionnaire uses a 4-point Likert scale, higher values representing higher job satisfaction. The questionnaire has 17 Items and the three subscales: Leadership, Working conditions and Development opportunities.

The survey was deployed over a span of three weeks and resulted in a sample size of n=91 of which n=77 were viable participants regarding their birth year and work experience.

This study can be described as an empirical, explanatory, fundamental study. This original group study collected and analyzed quantitative primary data. Furthermore, it is a non-experimental field study without repeated measurement with a cross-sectional design.

Data analysis

In order to test the proposed hypotheses, the used scales were tested for their reliability; internal consistency was calculated for this purpose. Variables were created that represent the constructs of emotion regulation and job satisfaction; these show the mean answer for the respective constructs. Although the variable emotion regulation is based on the difficulties in regulating emotions, in this study it indicates how well people can regulate their emotions. To test H1 the two variables were correlated with each other, a pearson correlation was calculated. To test H2, a linear regression was calculated with the variables mentioned. Additionally, descriptive results regarding emotion regulation and job satisfaction were analyzed. The data was analyzed using IBM-SPSS 30.

Findings and discussion of the results

Sample

The sample size was n=77 with a mean age of 24.04 years, 33,8% of the participants identified as male and 66,2% as female. No participant identified themselve as diverse.

Reliability

For the emotion regulation scale DERS-16 (translated to German) a reliability of ⍺=0.912 was calculated, indicating excellent reliability.

The used job satisfaction scale (FAGZ) showed an internal consistency of ⍺=0.924, also indicating excellent reliability.

Both findings go in line with previous research. For the DERS-16 Bjureberg et al. (2015) found an internal consistency of ⍺=0.92. The scales of the FAGZ were previously found to have an internal consistency of ⍺=0.865 to ⍺=0.940 (Siemeister, 2024).

Emotion regulation in the sample

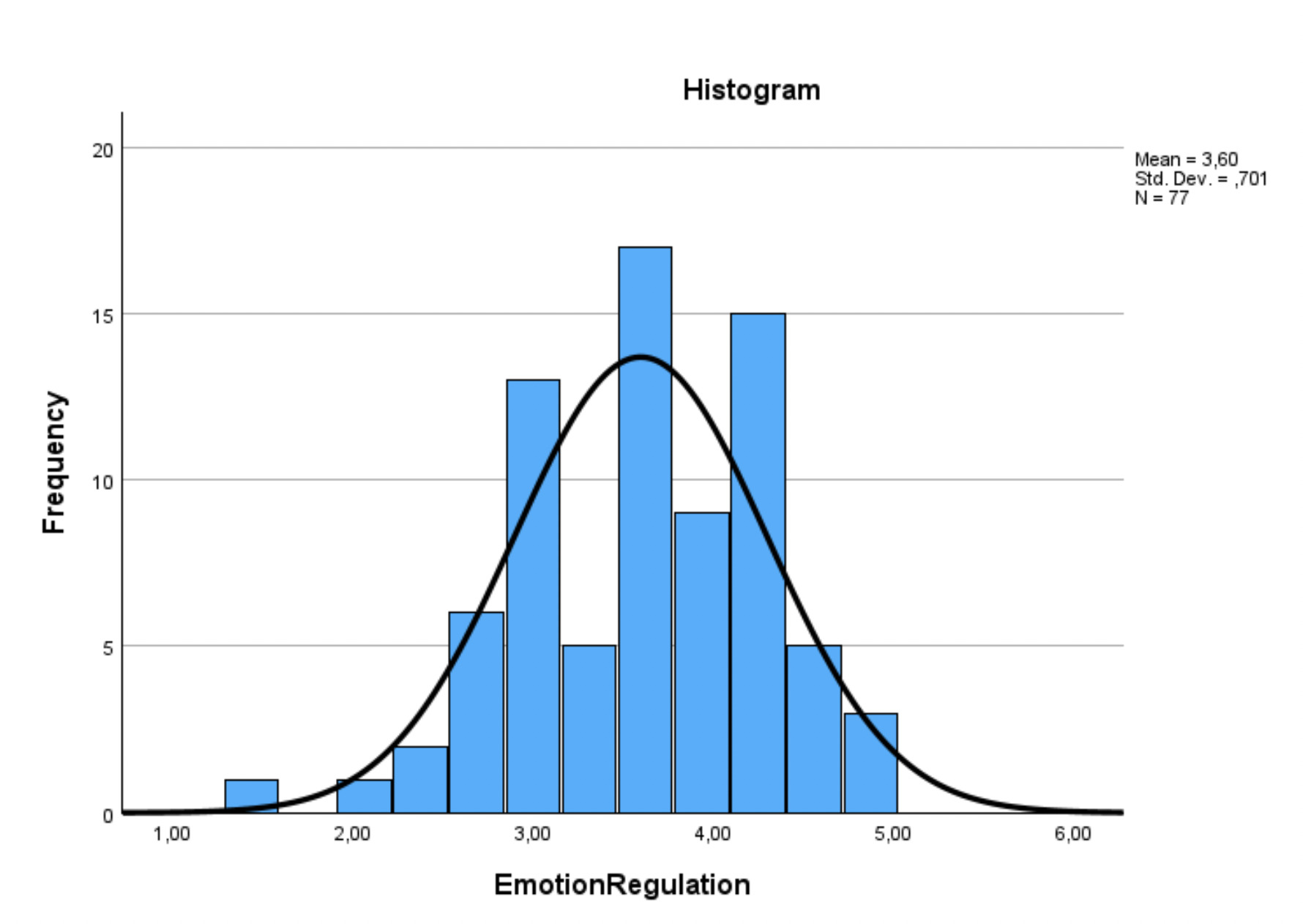

Emotion regulation in this sample had a mean of 3.60, with a standard deviation of 0.701 indicating moderate to low difficulty in regulating one’s emotions. Higher values represent a lower difficulty in emotion regulation, respectively better emotion regulation. The variable shows a normal distribution (y=-0.496, k=-0.026).

Figure 2: Histogram showing the distribution of emotion regulation in the sample, creation of the author

Job satisfaction in the sample

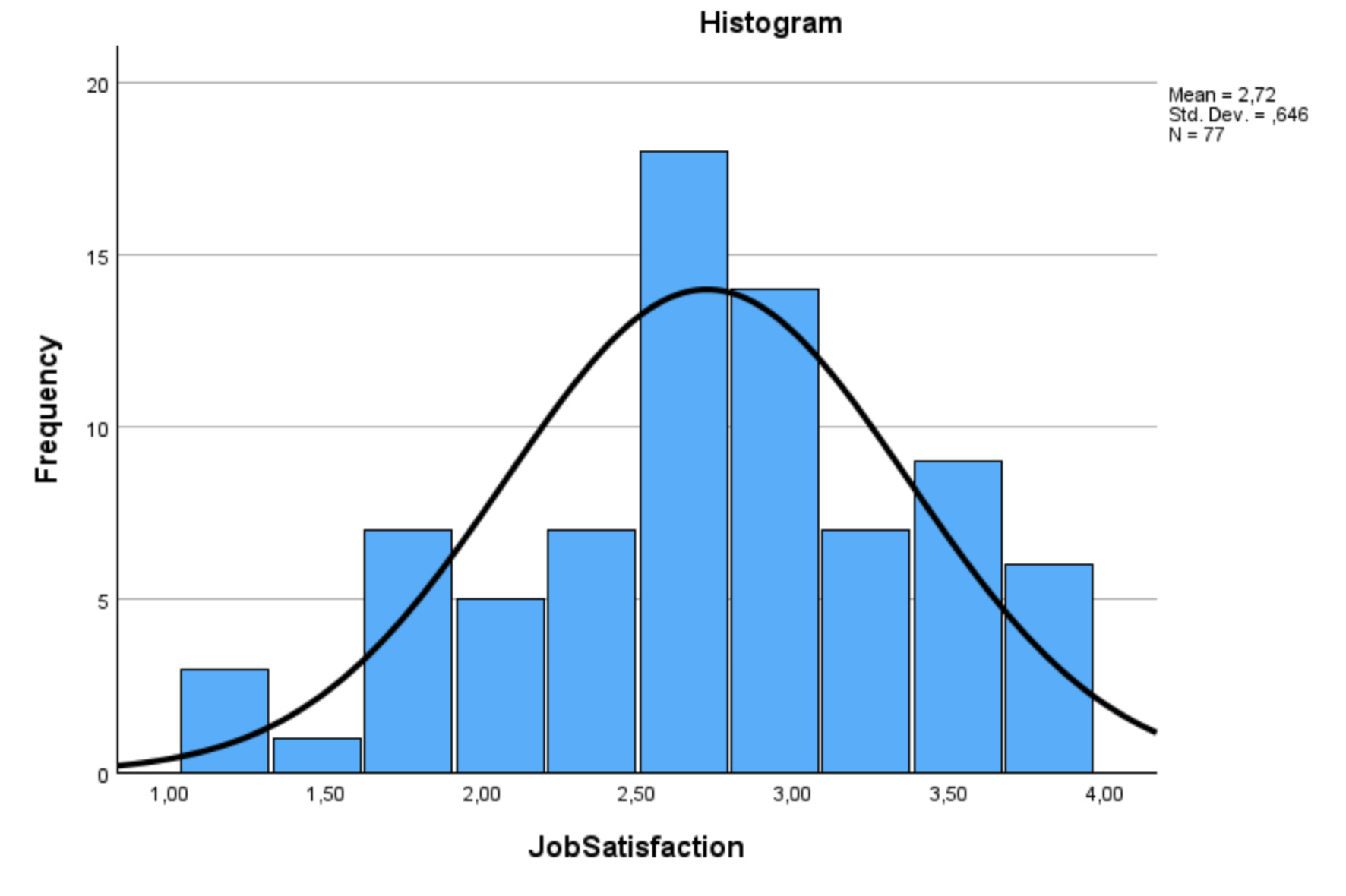

In this sample job satisfaction showed a mean of 2.72 with a standard deviation of 0.646, indicating medium to high levels of job satisfaction. Higher values represent higher levels of job satisfaction. The variable shows a normal distribution (y=-0.392, k=-0.282).

Figure 3: Histogram showing the distribution of job satisfaction in the sample, creation of the author

Hypothesis testing

There was no significant correlation found between the variables of emotion regulation and job satisfaction in this Generation Z sample (r=0.189, p=0.099). As a result, H1 was rejected. H2 can now also be discarded, as a regression analysis is negligible due to the lack of correlation.

This result stands in contrast to Pimentel & Pereira (2022) as well as Luque-Reca et al. (2022) who found significant correlations between the constructs. The results of this study are however supported by studies that could not establish significant direct effects between the constructs, on the other hand these could establish significant effects when factoring in mediating variables.

There are several factors that might explain the results of this study. Firstly, the job satisfaction of Generation Z is composed differently (Siemeister, 2024) than that of other generations, which may explain why no correlation was found in the Generation Z sample of this study. Additionally, two limiting factors of this study may also have contributed to the results. Firstly, although the German translation of the DERS shows high reliability (Gutzweiler & In-Albon, 2019) in a sample that can be considered as part of Generation Z, it is worded linguistically imprecisely. Secondly, a sample size of n=77 is quite small; a larger sample could show different results, as the population is better represented.

Conclusion

In summary, the main result of this study is that no significant relationship between emotion regulation and job satisfaction in this Generation Z sample was found. This may be explained by the fact that Generation Z’s job satisfaction is comprised differently than that of other generations.

Further research could build on these results and mitigate the mentioned limiting factors by adapting the wording of the German version of the DERS and aim to reach a larger sample. Additionally existing mediating effect should be reviewed for the Generation Z.

Companies should note that emotion regulation has neither shown a significant correlation with job satisfaction nor has emerged as a significant predictor of it within this Generation Z sample. This should be taken into account when planning human resources interventions for Generation Z employees. Although emotion regulation skills are an important organizational resource, they are not directly related to job satisfaction in Generation Z. Here companies should consider other factors.

About the Author

Philipp Siemeister holds a bachelor’s degree in media- and business psychology and is currently pursuing his master’s degree in business psychology at the Media University of Applied Sciences, Berlin, Germany. In his previous studies, he developed a questionnaire to assess job satisfaction tailored for Generation Z.

References

-

Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., Lundh, L., Bjärehed, J., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., Gumpert, C. H. & Gratz, K. L. (2015). Development and Validation of a Brief Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. Journal Of Psychopathology And Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x

-

Bridges, L. J., Denham, S. A. & Ganiban, J. M. (2004). Definitional issues in emotion Regulation research. Child Development, 75(2), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00675.x

-

Bulagang, A. F., Weng, N. G., Mountstephens, J. & Teo, J. (2020). A review of recent approaches for emotion classification using electrocardiography and electrodermography signals. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 20, 100363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2020.100363

-

Dose, J. J. (1997). Work values: An integrative framework and illustrative application to organizational socialization. Journal Of Occupational And Organizational Psychology, 70(3), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00645.x

-

Gutzweiler, R. & In-Albon, T. (2019). Überprüfung der Gütekriterien der deutschen Version der Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale in einer klinischen und einer Schülerstichprobe Jugendlicher. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 47(4), 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000506

-

Jordan, P. J., Ashkanasy, N. M. & Ascough, K. W. (2008). Emotional Intelligence in Organizational Behavior and Industrial-Organizational Psychology. In Oxford University Press eBooks (S. 356–375). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195181890.003.0014

-

Luque-Reca, O., García-Martínez, I., Pulido-Martos, M., Burguera, J. L. & Augusto-Landa, J. M. (2022). Teachers’ life satisfaction: A structural equation model analyzing the role of trait emotion regulation, intrinsic job satisfaction and affect. Teaching And Teacher Education, 113, 103668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103668

-

Madrid, H. P., Barros, E. & Vasquez, C. A. (2020). The Emotion Regulation Roots of Job Satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.609933

-

Mann, M. M. (2022). No More Stereotypes: Exploring the Work Value Priorities of Generation Z [Dissertation, Campbellsville University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2667765690

-

Moniarou-Papaconstantinou, V. & Triantafyllou, K. (2015). Job satisfaction and work values: Investigating sources of job satisfaction with respect to information professionals. Library & Information Science Research, 37(2), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.02.006

-

Nerdinger, F. W., Blickle, G. & Schaper, N. (2019). Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie. In Springer-Lehrbuch. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56666-4

-

Pimentel, D. & Pereira, A. (2022). Emotion Regulation and Job Satisfaction Levels of Employees Working in Family and Non-Family Firms. Administrative Sciences, 12(3), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030114

-

Puca, R. M. (2021). Emotionen im Dorsch Lexikon der Psychologie. https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/emotionen

-

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

-

Schutte, N. & Malouff, J. M. (2013). Adaptive Emotional Functioning: A Comprehensive Model of Emotional Intelligence. In Nova Science Publishers eBooks. https://rune.une.edu.au/web/handle/1959.11/13506

-

Siemeister, P. S. (2024). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung der Arbeitszufriedenheit angepasst an die Generation Z [Bachelor thesis]. Media University of Applied Sciences.