By Tim Thielmann, Supervision by Dr. Anna Rostomyan

Introduction

Every day, we enter a state of unconsciousness for six to eight hours, diving into a mysterious world shaped by dreams (Walker, 2017). Despite its critical role in emotional, cognitive, and physical restoration, sleep often goes unnoticed in discussions about workplace performance. Yet, it remains a cornerstone of human health and productivity. In recent years, sleep duration has been steadily declining among workers, raising significant concerns about the impact of this trend on their professional lives (CDC, 2017).

Current statistics highlight the gravity of the issue in the United States: over 40% of workers in industries such as production, healthcare, and food preparation report sleeping six hours or less per night (CDC, 2017). This widespread sleep deprivation, driven by demanding schedules and increasing workplace stress, underscores the need for a deeper understanding of sleep and its critical role in workplace performance (Barnes, 2011).

To address this growing concern, this article explores the question: “What is the impact of sleep on workplace performance?” By examining both the benefits of sufficient sleep and the detrimental effects of deprivation, this discussion aims to reveal how sleep shapes essential aspects of work, such as emotional regulation, decision-making, productivity, and learning. To answer this question, it is first necessary to explore the intricate mechanisms of sleep and the physiological and psychological roles they play.

Understanding Sleep

Sleep is a complex biological process essential for human survival and optimal functioning. It is regulated by two key mechanisms: sleep-wake homeostasis and the circadian rhythm (Holzinger, 2013). These mechanisms collaborate to ensure restorative sleep, cycling through distinct phases that contribute uniquely to physical, emotional, and cognitive well-being.

The Phases of Sleep

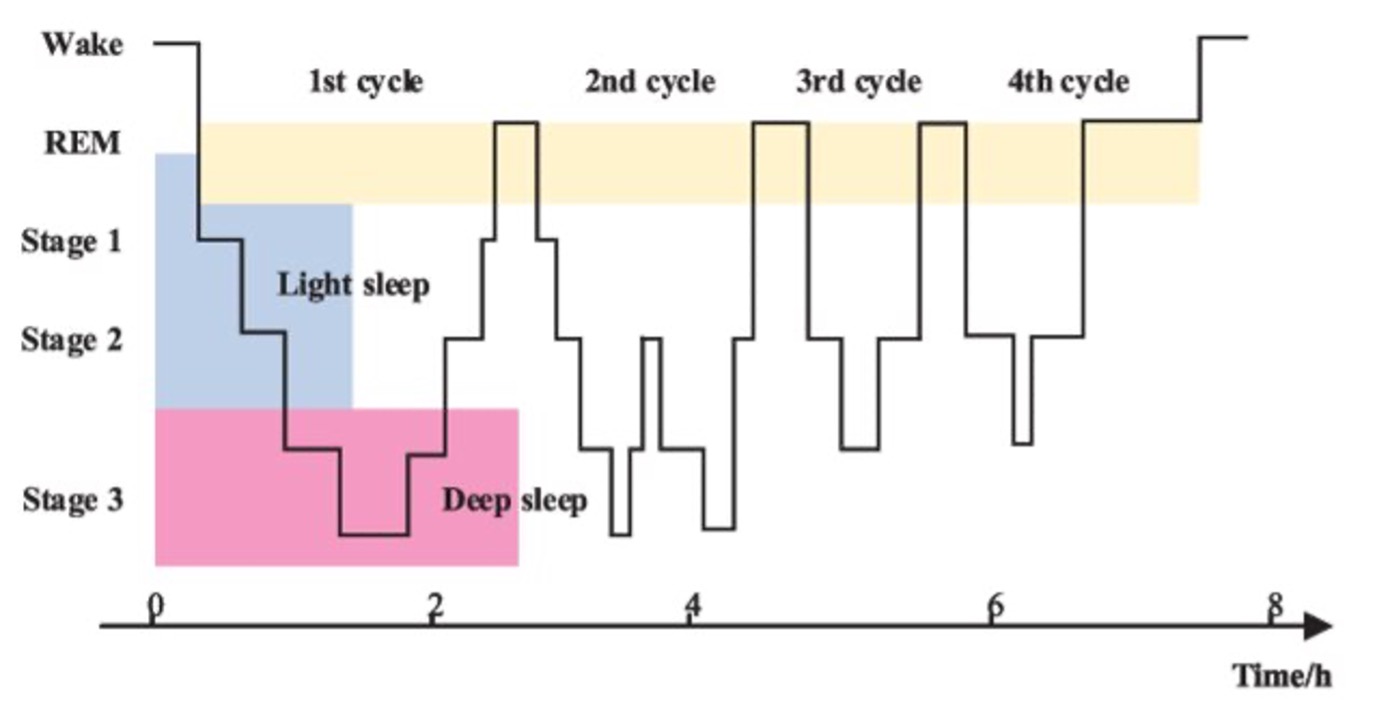

Sleep comprises multiple stages, broadly categorized into Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM), Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and Deep Sleep. These stages alternate in cycles throughout the night, each lasting approximately 90 minutes (Schulz, 2013). The transitions between these stages are illustrated in Figure 1, showcasing the distinct phases and their cyclic patterns throughout the sleep period (Zhang et al., 2022).

Figure 1: The general sleep transitions and sleep cycles. Adapted from Zhang, Zhou, & Liu (2022).

Non-REM Sleep: This phase includes the lighter stages of sleep, preparing the body for deeper, restorative rest. During Non-REM sleep, physiological activities decrease significantly, with reductions in heart rate, breathing, and body temperature (Schulz, 2013).

Deep Sleep: Also known as slow-wave sleep, this stage is vital for cellular repair, immune system strengthening, and the consolidation of declarative memory (Wießner, 2016). In deep sleep, the body reaches its most relaxed state, characterized by minimal brain activity and lowered blood pressure and heart rate.

REM Sleep: In this stage, the brain becomes highly active, processing emotions and integrating experiences into long-term memory. REM sleep is associated with creativity and problem-solving (Rasch, 2013). Despite the heightened brain activity, the body experiences temporary muscle atonia, while breathing and heart rate may become irregular.

The Circadian Rhythm

The circadian rhythm serves as the body’s internal clock, regulating the sleep-wake cycle and aligning it with environmental cues like light and darkness (Holzinger, 2013). This rhythm is primarily influenced by external factors, notably daylight exposure, which affects melatonin production, a hormone that induces sleep and controls your internal body clock (circadian rhythms).

Notably, the circadian rhythm evolves throughout an individual’s life. Younger individuals often have a delayed circadian rhythm, leading them to fall asleep and wake up later. As people age, this rhythm shifts earlier, explaining why older adults frequently wake up earlier in the morning (Schulz, 2013). Such natural changes can impact daily routines, productivity, and social interactions, especially in age-diverse workplace environments

Modern lifestyles heavily disrupt the circadian rhythm, particularly through widespread exposure to artificial lighting from electronic devices

Modern lifestyles heavily disrupt the circadian rhythm, particularly through widespread exposure to artificial lighting from electronic devices. The blue light emitted by screens suppresses melatonin production, which is produced by the pineal gland, delaying the body’s natural sleep cycle. This not only makes it harder to fall asleep but also increases the likelihood of frequent awakenings during the night, disrupting the entire sleep cycle. With nearly all individuals using smartphones, computers, or TVs during evening hours, the prevalence of disrupted circadian rhythms has significantly increased, contributing to insufficient and fragmented sleep across all age groups (Holzinger, 2013).

Chronotypes

Individual differences in sleep patterns, known as chronotypes, further influence sleep’s impact. Early birds, or “larks,” peak in productivity during the morning, while night owls function better in the evening. Mixed chronotypes fall between these extremes. Importantly, chronotypes are largely biologically determined and resistant to change when influenced externally, such as through imposed schedules or environmental pressures. Nevertheless, natural changes in chronotypes are evident over the human lifespan, with shifts toward earlier tendencies as individuals age.

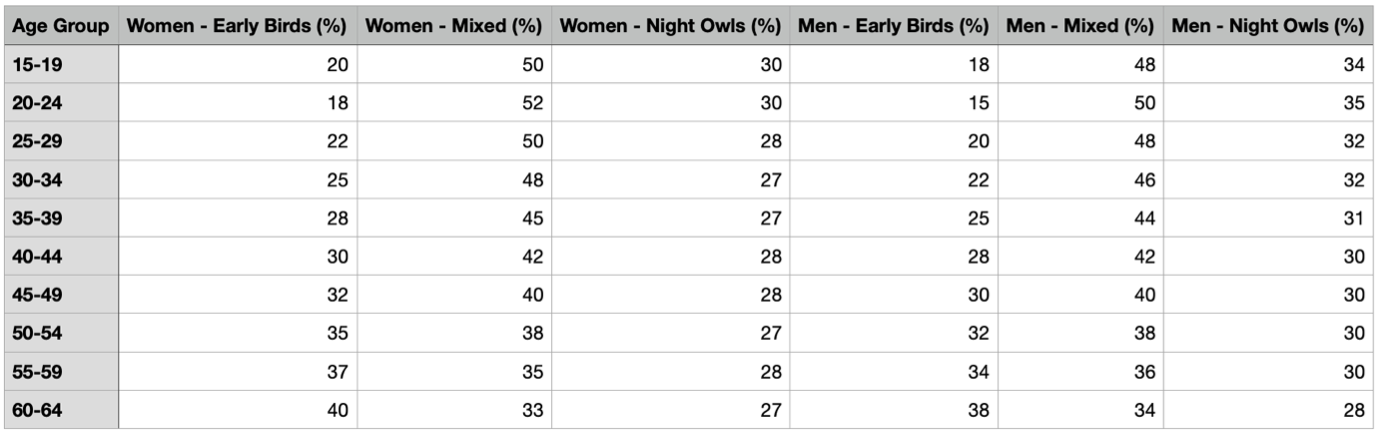

Figure 2: Chronotype distribution by age and gender. Data derived from Fischer, Lombardi, Marucci-Wellman, & Roenneberg (2017).

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of chronotypes across genders and age groups. Chronotypes exhibit notable shifts as individuals age: younger men and women tend to have a higher prevalence of night owl tendencies, whereas older individuals increasingly identify as early birds. For instance, among men, the proportion of early birds rises from 18% in the 15–19 age group to 38% in the 60–64 group, while the prevalence of night owls steadily declines. A similar trend is evident for women, with the percentage of early birds increasing from 20% to 40% across the same age range.

On average, 26% of men and 30% of women identify as early birds, while 31% of men and 29% of women are night owls. Mixed chronotypes dominate across genders, with approximately 43% of men and 41% of women falling into this category (Fischer et al., 2017).

The majority of individuals fall within the categories of mixed chronotypes or night owls, particularly among younger populations where this trend is most pronounced. This presents a systemic challenge, as standard work start times frequently fail to align with the natural sleep-wake patterns of a significant portion of the population. Such misalignment disrupts overall sleep quality and duration, leading to cumulative sleep debt, increased fatigue, and diminished cognitive and emotional performance, ultimately affecting workplace productivity and well-being (Saalwirth & Leipold, 2021).

While chronotypes naturally shift with age, gradually aligning with conventional work schedules, the impact on younger individuals and especially night owls remains substantial. As a result, individuals with night owl tendencies face significant challenges in adhering to early work schedules, further amplifying the adverse effects on productivity and health. These findings underscore the need for workplace policies that accommodate chronotypical diversity, fostering environments that promote both well-being and productivity.

Sleep’s Role in Workplace Performance

Sleep is a critical determinant of workplace success, influencing numerous factors that contribute to both individual and organizational outcomes. Among these, emotional regulation, decision-making, productivity and creativity, and learning and memory consolidation stand out as particularly impactful. Together, these aspects shape employees’ effectiveness, peer group dynamics, and the broader organizational culture.

Emotional Regulation

A well-rested individual brings balance and composure to the workplace. Sufficient sleep allows the brain to better regulate emotions, reducing stress and promoting harmony in interactions. Employees who sleep at least seven hours per night demonstrate 23% greater emotional stability, enabling them to navigate conflicts with patience and maintain positive team relationships (Barnes, 2011). This emotional resilience fosters collaboration, boosts morale, and strengthens workplace cohesion.

Sufficient sleep allows the brain to better regulate emotions, reducing stress and promoting harmony in interactions.

In contrast, sleep deprivation throws emotional regulation off balance, heightening irritability and impulsivity. The brain’s prefrontal cortex, essential for managing emotions, becomes less effective, leading to a 60% increase in emotional lability among sleep-deprived individuals (Rasch & Born, 2013). These shifts can create workplace tension, increase conflicts, and weaken team cohesion, ultimately diminishing productivity and morale (Sachdeva & Sharma, 2021).

The above comes to suggest that for a better emotion regulation and for a better performance at the workplace, individuals should have at least 7-9 hours sleep per day so that to be able to better navigate through workplace challenges and life’s adversities.

Decision-Making

Good decision-making is rooted in clarity and confidence, qualities that thrive with sufficient sleep. REM sleep, in particular, enhances problem-solving skills and neural processing, enabling individuals to perform 42% better on complex tasks compared to those who are sleep-deprived (Rasch, 2013). Rested employees are more adept at evaluating risks and benefits, making them reliable contributors in high-pressure situations.

Sleep deprivation, however, clouds judgment and slows cognitive processing. Studies show that individuals operating on insufficient sleep are 30% less accurate in decision-making and far more prone to errors in high-stakes scenarios (Hoermann et al., 2021). When poor sleep quality becomes a pattern, impulsive choices and avoidable mistakes can disrupt workflows and jeopardize organizational goals (Sachdeva & Sharma, 2021).

The above comes to suggest that in case we want to do better decision-making and to ameliorate the functioning of our higher cognitive processes, we have to pay a closer attention to a quality sleep that has the utmost power of improving the aforementioned processes.

Productivity and Creativity

Productivity thrives when energy levels are replenished and creativity is nurtured, a dual benefit of adequate deep sleep. Employees who sleep well are 35% more productive and commit 50% fewer errors compared to their sleep-deprived counterparts (Wießner, 2016). Creative industries, in particular, see a notable advantage, as rested individuals excel at reorganizing and integrating information, leading to innovative ideas and solutions.

On the other hand, chronic sleep deprivation drags down productivity. Workers with poor sleep quality face an average 29% decline in output, while errors and delays increase significantly (Munafo et al., 2016). Insomnia symptoms alone contribute to the loss of approximately 7.8 productive days per employee annually, further compounding workplace inefficiency (Kessler et al., 2011).

This comes to suggest that sleep deprived individual perform worse than those employees who have had a good night’s sleep, which hints to the fact that performance levels and quality sleep are very tightly interlinked.

Learning and Memory Consolidation

Every training session, brainstorming meeting, or new skill learned relies on the brain’s ability to consolidate information, a process fundamentally tied to sleep. Both slow-wave and REM sleep play critical roles in enhancing memory retention, with individuals who sleep seven to nine hours retaining up to 40% more information than those with insufficient sleep (Rasch, 2013). This advantage allows employees to adapt quickly to new challenges and continuously grow in their roles.

Conversely, inadequate sleep disrupts the memory consolidation process, leaving employees struggling to retain and apply new knowledge. Poor sleep quality is linked to a 30% decline in job performance related to learning and adaptability (Sachdeva & Sharma, 2021). Over time, these gaps in skill retention hinder both individual development and organizational innovation.

Improving Sleep for Better Workplace Performance

Having explored the profound effects of sleep on workplace performance, it becomes essential to address the solutions. While the challenges posed by insufficient sleep are significant, there are actionable strategies that organizations, managers, peer groups, and employees can implement to mitigate these effects. By fostering healthier sleep habits across these levels, workplaces can enhance both individual well-being and organizational success, also by means of providing their employees with correlated training and/or introducing nap pods.

Organizational Strategies

Organizations play a vital role in promoting sleep health by creating an environment that supports work-life balance and well-being. Policies such as flexible working hours and limits on overtime can significantly reduce the strain on employees’ sleep schedules. Additionally, workplaces designed with stress-reducing elements, such as natural lighting and quiet spaces, help employees maintain better sleep quality. Introducing wellness programs or offering sleep education workshops further empowers employees to prioritize rest, fostering a culture of health within the organization. Research indicates that organizations implementing flexible schedules see up to a 20% reduction in employee sleep deprivation, contributing to higher productivity and morale (Reddy et al., 2020).

Management Approaches

Managers and leaders influence sleep health through the behaviors they model and the expectations they set. Encouraging leaders to prioritize their own sleep and advocate for reasonable workloads creates a ripple effect that benefits the entire team. Setting realistic deadlines and avoiding last-minute demands reduces employee stress, ensuring that workloads do not encroach on personal rest time. For night-shift workers, providing sleep-friendly environments, such as nap rooms or designated rest breaks, can mitigate the negative effects of irregular schedules. Studies show that leaders who model a balanced approach to work and rest improve team productivity and morale by 15% (Barnes, 2011).

Social and Peer Group Dynamics

The influence of social dynamics on sleep health is significant. Fostering a workplace culture where colleagues respect boundaries regarding after-hours communication is crucial. Peer support systems that promote healthy behaviors, including prioritizing sleep, help reduce workplace stress and its associated sleep disturbances. Additionally, discouraging group activities that disrupt sleep, such as late-night social events or excessive weekday drinking, contributes to healthier habits. Research highlights that teams with strong social support report 25% fewer sleep-related issues due to reduced workplace stress (Hoermann et al., 2021).

Employee Actions

Mindfulness meditation and breathing exercises are proven methods to reduce stress and improve sleep quality.

Employees themselves can adopt several strategies to improve their sleep quality and its subsequent impact on workplace performance. Practicing good sleep hygiene—maintaining consistent sleep schedules, avoiding caffeine and screen exposure before bedtime, and creating a relaxing pre-sleep routine lays the foundation for better rest. Mindfulness meditation and breathing exercises are proven methods to reduce stress and improve sleep quality. Recognizing the direct link between sleep and professional success motivates employees to prioritize rest, resulting in measurable improvements in their well-being and performance. Studies demonstrate that sleep hygiene education can improve sleep quality by 30% and reduce insomnia symptoms significantly (Sachdeva & Sharma, 2021).

Conclusion: A Collective Responsibility for Better Sleep

Sleep, as explored throughout this article, is influenced by a multitude of interconnected factors, spanning individual habits, social interactions, management practices, and organizational policies. While companies and managers can play a critical role in fostering a sleep-supportive environment, the ultimate responsibility for improving sleep lies with the individual. Sleep is deeply personal, shaped by one’s unique biology, behaviors, and lifestyle choices.

Nevertheless, as individuals within a workplace context, we are part of a broader living continuum with significant social impact and shared responsibility. Organizations and leaders have the opportunity to create environments that encourage healthier behaviors, reflecting the principles of new work. This modern perspective emphasizes that work should not only drive productivity but also actively support the well-being of employees. By promoting flexible schedules, modeling healthy behaviors, and fostering a culture of respect and collaboration, workplaces can empower individuals to prioritize their health, including sleep.

Ultimately, achieving better sleep and its associated workplace benefits requires collective effort. It is not solely about assigning responsibility but about acknowledging the interconnectedness of all levels: individual, social, and organizational. By understanding and addressing these dynamics, we can cultivate a more sustainable and human-centered work culture, where sleep is valued as an integral part of both personal and professional success.

References

-

Barnes, C. M. (2011). Sleep and organizational behavior: Implications for workplace performance. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 69–91.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Short sleep duration among workers—United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(8), 1–8.

-

Fischer, D., Lombardi, D. A., Marucci-Wellman, H., & Roenneberg, T. (2017). Chronotypes in the US – Influence of age and sex. PLOS ONE, 12(6), e0178782. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178782

-

Holzinger, B. (2013). Sleep, circadian rhythms, and sleep disorders: An introduction to sleep science. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 90(3), 3–10.

-

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Coulouvrat, C., Hajak, G., Roth, T., Shahly, V., & Shillington, A. C. (2011). Insomnia and the performance of US workers: Results from the America Insomnia Survey. Sleep, 34(9), 1161–1171.

-

Munafo, M. R., Stamatakis, E., & Wareham, N. J. (2016). Sleep deprivation and workplace performance. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(7), 671–678.

-

Rasch, B., & Born, J. (2013). About sleep’s role in memory. Physiological Reviews, 93(2), 681–766.

-

Reddy, A. B., O’Neill, J. S., & Maywood, E. S. (2020). Circadian rhythms and workplace health. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 31(8), 543–555.

-

Saalwirth, C., & Leipold, B. (2021). Chronotypes and their impact on workplace productivity. Sleep Health, 7(2), 198–204.

-

Sachdeva, S., & Sharma, P. (2021). Sleep quality and job performance in working professionals. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(3), 199–208.

-

Schulz, H. (2013). Phases of sleep and their impact on human health. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 9(5), 489–495.

-

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

-

Wießner, M. (2016). The role of deep sleep in workplace productivity. Neurobiology of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms, 1(1), 15–23.

-

The general sleep transitions and sleep cycles. Adapted from Zhang, X., Zhou, X., & Liu, Q. (2022). AI-empowered virtual reality integrated systems for sleep stage classification and quality enhancement. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360908182_

AI_Empowered_Virtual_Reality_Integrated_Systems_for_Sleep_Stage_Classification_and_Quality_Enhancement.

-

Fischer, D., Lombardi, D. A., Marucci-Wellman, H., & Roenneberg, T. (2017). Chronotypes in the US – Influence of age and sex. PLOS ONE, 12(6), e0178782. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178782