The chief strategy officer (CSO) position has recently been gaining prominence in European firms. However, little is known about this new executive role. In this article, the authors report some of their findings from a major research program that involved two surveys of CSOs and give a portrayal of the CSO’s role in continental European firms. The article further highlights how CSOs deal with the current uncertainty and how they professionalise their firm’s strategy activities.

Many European firms have been faced with increasing uncertainty and complexity over the past few years. The recent financial and European debt crises, fast-paced industry change, increased competitiveness, changing customer needs, new technologies, and more complex organisational structures of multibusiness and multinational corporations, are but a few examples. Owing to these developments, the need for professional strategy development and execution is now greater than ever before. As a consequence, firms increasingly often opt for a chief strategy officer (CSO), a senior executive who heads a dedicated strategy or corporate development department, which may employ more than a hundred full-time strategists.1

We observed that the CSO position has recently become more prevalent in European firms and that there is a lack of knowledge on this new executive role. Therefore, the University of St. Gallen and Roland Berger Strategy Consultants initiated a major research program on the CSO’s role in 2011. Specifically, we conducted a survey with 90 CSOs of the 250 largest firms in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland in 2011, and another one with 54 CSOs from the same sample in 2012.2 In addition, we conducted interviews and hosted several roundtables with selected CSOs from major corporations such as Daimler, Deutsche Bank, Migros and Siemens.

The purpose of this article is to give a portrayal of the CSO’s role in continental European firms and to illustrate how they deal with the uncertainties that their firm’s currently face. Since there have been first efforts to understand the CSO’s role in US and UK firms, we point out the important similarities and differences between the contexts.3 We also highlight what is generally needed to strategise effectively in these difficult times. CSOs are on the rise and increasingly qualify as future CEOs. Our findings therefore not only inform current strategists, other executives and consultants, but also practitioners and students eager to learn about this new role as a career opportunity.

The nature of the CSO

Although the CSO position is a relatively new phenomenon, it has quickly become widespread in European firms. Almost all the firms in our study’s sample whose annual sales exceed one billion Euros have a CSO among their executive ranks. 76 per cent of the CSOs in our 2012 study report directly to the CEO and, thus, have a rather powerful position. They are, however, very rarely located on the first level of the organisational hierarchy, namely in the formal top management team (e.g. “Vorstand” or “Geschäftsleitung”). This also distinguishes the CSOs in European firms from their peers in the US, where almost 50 per cent were official members of their firm’s executive board in 2008.4

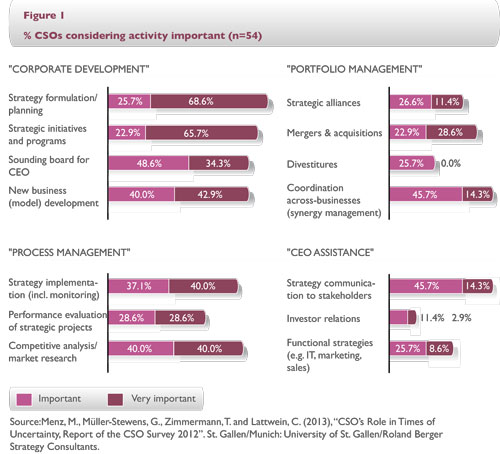

While we use “chief strategy officer” as an umbrella term for the strategy heads, the firms in our sample use many different titles for this position, for example, “head of corporate development”, “vice president strategy” and “senior vice president corporate strategy”. However, we also observe that European firms increasingly often use the title “chief strategy officer”. Although these variations indicate potential differences in the CSO’s role between firms,5 we find that several core activities are usually part of the CSO’s role and the respective strategy department (see Figure 1).

Firstly, CSOs are responsible for their firm’s corporate development activities. In our sample, 94 per cent of the CSOs consider strategy formulation/planning important or very important, and 89 per cent perceive strategic initiatives as (very) important activities that are part of their job. Moreover, CSOs often act as a sounding board for the CEO or the senior executive team. Interestingly, exploration and growth-oriented activities, for example new business (model) development, seem to be (very) important aspects of the CSO’s role.

Secondly and similarly, the CSO’s role involves portfolio management activities, such as strategic alliances, mergers and acquisitions, and divestitures. Thirdly, CSOs are typically engaged in managing their firm’s strategy process, which includes diverse tasks, such as competitive and market analyses and strategy implementation and monitoring. Finally, these executives may have an array of diverse activities that are related to other functional areas, such as marketing, corporate social responsibility and finance. We summarise these specialist tasks as “CEO assistance”.

While no standard career path seems to lead to a CSO position, several qualifications and types of experience are frequently found among the CSOs in European firms. About two third of the CSOs in our sample have a master’s degree in economics or business administration and about 40 per cent hold a doctoral degree, which is customary for senior executives in German-speaking firms. CSOs’ functional background varies; about one third has general management experience, while the rest have worked in diverse functional areas, such as strategy, marketing or finance. There is also some variance in their firm-specific experience; more than 40 per cent of the CSOs had less than two years’ experience in the focal firm when they were appointed as CSO.

The CSO’s role in times of uncertainty

CSOs in European firms currently face several challenges and opportunities. Uncertainty in the firm environment has serious implications for European firms’ and their CSO’s strategy activities. These issues affect all aspects of firms’ strategy processes and, thus, the CSO’s role itself.

Changes in the CSO’s role

A comparison between our 2011 and 2012 studies’ results reveals that CSO activities in the areas of strategy process management, corporate development and portfolio management have become more important. This is consistent with our observation that the CSO’s role has generally become more demanding. In addition, strategy implementation, which is typically at the heart of the CSO’s role, has gained importance. Conversations with CSOs in European firms revealed that, over the past few years, their role has evolved from focusing on strategic planning to being responsible for the entire strategy process, specifically implementing their firm’s strategy.

It is also noteworthy that acquisitions have become less relevant to the CSOs in our sample, while the importance of divestitures has increased. CSOs are in charge of refocusing or restructuring their firm’s business portfolio. These and activities to coordinate the firm’s businesses are becoming increasingly important aspects of the CSO’s role. This indicates that there is a need to realise efficiency synergies, for example, by means of joint procurement and supply chain management. In sum, these and other short-term shifts in the CSOs’ activities are a consequence of the increasing uncertainty and volatility in firms’ environment. They present a major challenge for these executives.

Leaner strategy process

CSOs agree that the increased uncertainty due to market volatility and other issues has a significant impact on their firm’s corporate development. Most CSOs consider a leaner strategy process key to being able to cope with the current situation. Our study shows that instead of addressing the environment’s increased complexity with an equally complex strategy process, CSOs focus on a few relevant aspects.

Accordingly, many of them, especially the CSOs of the larger firms in our study sample, do not think that the recent developments necessitate an increase in the number of strategists in their department. This is remarkable, given the small size of these central strategy departments. The average strategy department consists of about 11 full-time strategists (the Median is six employees) and only a few firms, for example, Deutsche Bank or Siemens, have many more strategists at their headquarters. Hence, CSOs do not seem to require more resources to address the recent challenges.

Megatrends as opportunity

A key task of the CSO is to consider the potential effect of long-term developments, frequently labelled “megatrends”, such as climate change, urbanisation, and demographic change, and integrate these into their firms’ strategic planning processes. Using the CSOs’ assessment of their firm’s financial performance to draw distinctions between them, we notice that the CSOs of high-performing firms are more likely to see megatrends as an opportunity than those of low performing firms. Otherwise, CSOs of low-performing firms are more likely to see megatrends as a threat than those of high-performing firms. Overall, CSOs of high-performing firms seem to be more long-term oriented and have a more optimistic view of the future than those of low-performing firms.

CSO’s collaboration with other functions

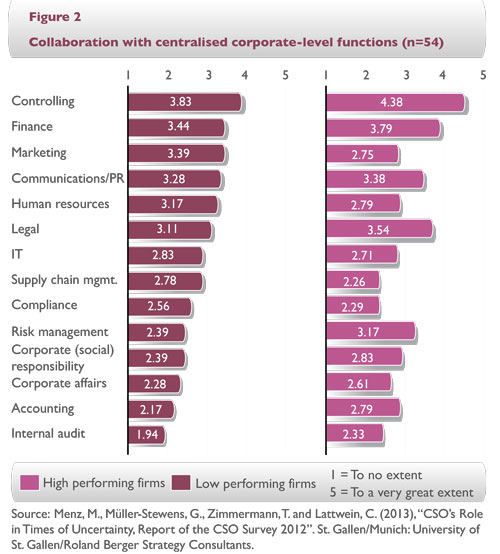

To address recent developments, firms increasingly launch strategic initiatives that involve cross-functional collaboration. There has recently been an increase in the number of centralised corporate functions and of respective functional top managers.6 Questions regarding which functions should and should not be centralised and how to integrate diverse functions into the firm’s strategy processes and strategic initiatives are critical.7 CSOs regard collaboration between strategic planning, risk management and operational planning as particularly critical to successfully dealing with current uncertainties.

Our study reveals considerable differences between high-performing and low-performing firms (see Figure 2). CSOs of more successful firms cooperate with selected growth-oriented functions, such as marketing, significantly more than CSOs of less successful firms. CSOs of low-performing firms more often collaborate with bottom-line functions, such as controlling, risk management and accounting, than their peers of more successful firms. Generally, we find that CSOs of high-performing firms are more likely than those of low-performing firms to focus their cross-functional collaboration efforts on specific selected functions.

Measuring CSO’s value creation

The CSOs in our study sample considered it important to measure the value creation of a firm’s centralised strategy department in general. However, this becomes even more relevant in times of uncertainty when there is increased pressure to justify the costs of a firm’s various centralised corporate functions. Most CSOs consider measuring their department’s value creation a (very) difficult task. They indicate that the strategy department’s value creation is primarily measured by the CEO’s perception thereof.

Fortunately, many CSOs currently professionalise their firm’s strategy activities, for example, by developing standardised methods to measure the performance of their strategy departments. While many firms still do not have a transparent and quantifiable way to regularly measure the impact of the strategy department’s value creation, CSOs are aware of the need for measures that rely on either objective criteria or the judgments of key stakeholders other than the CEO, such as divisional heads.

The future of the CSO

Since uncertainty in the firm environment and organisational complexity are likely to further increase in the future, professional strategy activities will become more important. European firms seem to increasingly often appoint CSOs as members of their firm’s executive board, which has been quite common in US firms for a while. For example, the reinsurance firm Swiss Re recently announced: “Appointing John R. Dacey [Head Group Strategy & Strategic Investments] to the Group Executive Committee underscores the central role played by Group Strategy & Strategic Investments in advancing our strategy and exploiting our research expertise”.8 These firms highlight the importance of strategy by putting their CSOs in more powerful and influential positions.

In addition, the growing importance of strategizing capabilities can be observed in the increasing number of firms that appoint former CSOs – be it from inside or outside of the firm – to senior executive roles or even as their CEO. A former CSO of the electrical engineering giant Siemens, for example, became a member of the firm’s executive board. And recently, firms in different industries, such as the second-largest German airline Air Berlin, sportswear firm Puma and railway firm Deutsche Bahn, have appointed former CSOs as their CEO. In conclusion, the number of firms that select a CEO who has experience as a CSO will ultimately indicate the importance of professional strategy activities.

How Digital Marketing Can Help

At this point, the current health crisis the world is experiencing brings many uncertainties. Businesses are forced to shift from traditional means to digital sales and marketing. So, how can digital marketing help during these times?

Students are the country’s future professionals. Learning the basic and advanced concepts of digital marketing makes them better online marketers, managers, and innovators. They’re the ones who’ll nurture artificial intelligence and find other innovative ways to make digital marketing broader, more convenient, and accessible to all.

1. Help Businesses Promote Products and Services Digitally

Digital marketing encompasses a wide array of promotional and advertising elements over the internet through digital devices, such as smartphones, smart TVs, tablets, and wearable devices. From traditional marketing, such as brochures, store product displays, and newspaper ads, businesses need to shift to digital marketing to keep up with today’s “new normal.”

Despite the ongoing restriction laid by the government, a digital marketing agency can help business owners achieve their business goals. Digital marketing related courses are available online, and various platforms offer free access to their modules and tutorials, such as Facebook and HubSpot.

2. Learning Digital Marketing Strategies to Open New Opportunities

Digital marketing strategies have evolved since the internet came to existence, from business card type websites to full-blown e-commerce and social media platforms. For those who are interested, professionalizing digital marketing opens doors to new job opportunities without needing to leave home. It’s because most digital marketing jobs can be done remotely or at home.

Here’s how:

- Invest in a reliable computer (laptop or PC) and internet connection.

- Attend online classes or short courses on digital marketing.

- After earning enough credentials and experience, a digital marketer can start a career by applying through online job portals, like Upwork and Fiverr.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to give a portrayal of the CSO’s role in continental European firms and to illustrate how they deal with the uncertainties that their firm’s currently face. Since there have been first efforts to understand the CSO’s role in US and UK firms, we point out the important similarities and differences between the contexts.

We also highlight what is generally needed to strategise effectively in these difficult times, like the current pandemic crisis through digital marketing. CSOs are on the rise and increasingly qualify as future CEOs. Our findings therefore not only inform current strategists, other executives, and consultants, but also practitioners and students eager to learn about this new role as a career opportunity.

About the Authors

Markus Menz is an assistant professor of strategic management and the executive director of the master in business management programme at the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland). Previously, he was a visiting fellow at Harvard University. His research focuses on organisational units, teams, and individual executives involved in strategic leadership, particularly chief strategy officers. His work has been published in leading academic and practitioner journals, such as Strategic Management Journal and Journal of Management.

Günter Müller-Stewens is a professor and the managing director of the Institute of Management at the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland). His research interests centre on corporate strategy, mergers and acquisitions and the strategy process. He has co-authored several strategy books, most recently Corporate Strategy & Governance. He is the academic director of the master of strategy and international management (SIM) programme at the University of St.Gallen, which is ranked Number 1 in the Financial Times’s global ranking.

Tim Zimmermann is a partner at Roland Berger Strategy Consultants in Munich. His functional expertise covers all aspects of organisation, process reorganisation and human resources management. He has broad experience in developing and implementing management tools, processes and systems, especially in reorganisation situations such as corporate performance programmes or post-merger integrations. His specialties include modelling, benchmarking and shaping corporate management functions as part of corporate overhead.

Christian Lattwein is a senior consultant at Roland Berger Strategy Consultants in Frankfurt. His cross-industry expertise comprises corporate strategy, strategy implementation, corporate finance and valuation as well as performance management. His core competence is in quantitative and qualitative modelling of strategic scenarios and evaluation of strategic options in times of uncertainty.

References

1. Menz, M. and Scheef, C. (2013), “Chief Strategy Officers: Contingency Analysis of Their Presence in Top Management Teams”, Strategic Management Journal, forthcoming, DOI: 10.1002/smj.2104, 1-22.

2. Menz, M., Müller-Stewens, G., Henkel, C. B. and Reineke, B. (2012), “The Role of Chief Strategy Officers 2011”. St. Gallen/Munich: University of St. Gallen/Roland Berger Strategy Consultants. Menz, M., Müller-Stewens, G., Zimmermann, T. and Lattwein, C. (2013), “CSO’s Role in Times of Uncertainty, Report of the CSO Survey 2012”. St. Gallen/Munich: University of St. Gallen/Roland Berger Strategy Consultants.

3. Angwin, D., Paroutis, S. and Mitson, S. (2009), “Connecting up strategy: Are senior strategy directors the missing link?” California Management Review, 51(3): 74-94. Breene, R. T. S., Nunes, P. F. and Shill, W. E. (2007), “The Chief Strategy Officer”, Harvard Business Review, 85(10): 84-93. Menz, M. and Scheef, C. (2013), “Chief Strategy Officers: Contingency Analysis of their Presence in Top Management Teams”, Strategic Management Journal, forthcoming, DOI: 10.1002/smj.2104, 1-22.

4. Menz, M. and Scheef, C. (2013), “Chief Strategy Officers: Contingency Analysis of their Presence in Top Management Teams”, Strategic Management Journal, forthcoming, DOI: 10.1002/smj.2104, 1-22.

5. Menz, M., Müller-Stewens, G., Henkel, C. B. and Reineke, B. (2011), “Die vier Gesichter des Chefstrategen”, Harvard Business Manager, 33(11), 6-9. Menz, M., Müller-Stewens, G., Henkel, C. B. and Reineke, B. (2012), “The Role of Chief Strategy Officers 2011”. St. Gallen/Munich: University of St. Gallen/Roland Berger Strategy Consultants.

6. Guadalupe, M., Wulf, J. and Li, H. (2012), “The Rise of the Functional Manager: Changes Afoot in the C-Suite”, The European Business Review, 2012(May-June): 9-13. Menz, M. (2012), “Functional Top Management Team Members: A Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda”, Journal of Management, 38(1), 45-80.

7. Campbell, A., Kunisch, S. and Müller-Stewens, G. (2012), “Are CEOs Getting the Best from Corporate Functions?”, MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(3): 12-14. Campbell, A., Kunisch, S. and Müller-Stewens, G. (2011), “To Centralize or Not to Centralize”, McKinsey Quarterly, 2011(June): 1-6.

8. Press Release of Swiss Re, http://www.swissre.com/media/news_releases/nr_20121019_gec.html (accessed on March 20, 2013).