By Klaus Heine

Most entrepreneurs today do not just wish to make money, but also aim to serve a good purpose. They combine self-discovery with business-modelling and brand-building, but struggle to exploit the full spectrum and true potential of symbolic brand benefits. This article will help businesspeople combine these tasks as the author outlines the Brand-Building Canvas, explains why and how to use it, and briefly describes each of the brand-building elements.

As a professor in luxury marketing at emlyon business school, I concentrate on how to build luxury brands for many years. There is no other segment in which symbolic consumer benefits play a greater role than for luxury brands. A big part of the brand-building process deals with the creation of ‘meaning’. Building a (luxury) brand is about developing brand identity. To find out what you want your brand to stand for, you can make use of a brand identity planning model that provides an overview about what brand elements should be considered and how they will inter-relate. However, there exist surprisingly few alternative brand identity models (e.g. by Aaker, 1997; De Chernatony, 1999; Esch 2008; Kapferer 2012). The existing models miss some aspects and do not allow to cover the full spectrum of brand meaning. There are some important components missing in some models (e.g. brand vision). As most commonly used models were created decades ago, they do not account for the tremendous changes in marketing and branding caused by digitalisation. In addition, they only focus on brand-building, although there is much overlap between the tasks of brand-building and business-modelling.

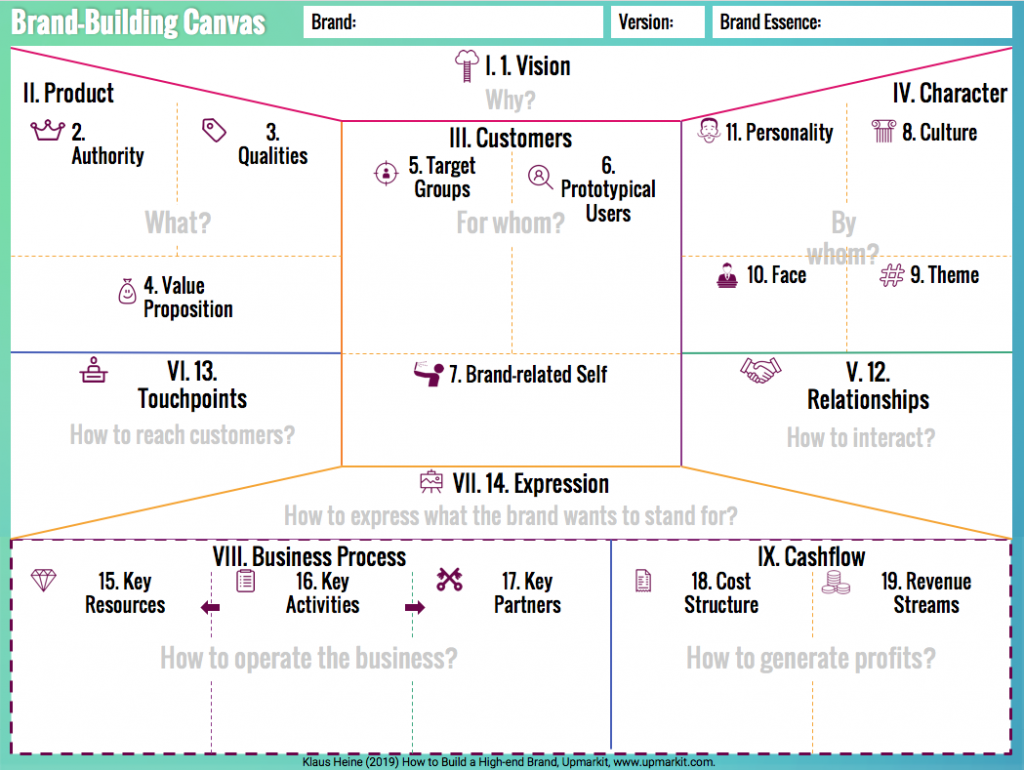

The Business Model Canvas by Osterwalder and Pigneur (2014) is a very useful tool to think through business ideas. But entrepreneurs never just create a business – they always need to create a brand at the same time. Even more today, the symbolic meaning, brand’s purpose, and story are not just a nice add-on, but in many cases, the central idea of a new business. Building a business also means building a brand. From the customer’s point of view, a brand is not distinct from the business – they are ONE. Therefore, the Business Model Canvas was combined with a new brand identity framework into the Brand-Building Canvas (see Figure 1; Heine, 2019). It includes new brand elements and covers all aspects in the Business Model Canvas and the major brand identity frameworks. Therefore, it can be used to analyse and develop a business model and a brand’s identity. Blocks VIII (Business Process) and IX (Cashflow) are only relevant for business modeling (see Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2014).

If you focus on brand-building, you need to consider only the first seven blocks of the Brand-Building Canvas. They are arranged simply as follows: the Vision is on top (block I); the Product (business idea) is the starting point (block II); the Customers are in the centre of attention (block III); it follows the Brand Character that tells the meaning behind the product on the left (block IV); Relationships describe the mode of conduct between the brand (IV) and the customers (III) (block V); Touchpoints connect the products (II) with the customers (III) (block VI) – and all this is symbolised by Brand Expressions, placed at the bottom (block VII). Some blocks are further divided into additional brand-building elements. In total, the template consists of 14 components, which are briefly introduced below.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Block I: Vision

Similar to a great dream, a vision is a picture of the preferred future of a brand, but also of the future of society and the subculture or industry in which the brand operates. As part of the vision, the brand purpose outlines a brand’s fundamental reason for existence and how it aims to make the world a better place. As a brand’s overarching guiding idea, the vision shapes a brand’s identity and influences all other aspects of marketing and branding. Therefore, it must be part of the brand identity (but is not included in most major models). In addition, it makes no sense to class the vision as a subcategory of another brand identity element (e.g. part of ‘Brand Tonality’ by Esch, 2017), but it should be placed on top of the brand identity model.

Block II: Product

Product-related associations are a major component of brand image (Keller, 2003). As most important components of brand image play the biggest role in shaping people’s opinion about a brand, they should be included in brand identity planning. Whatever is unimportant in shaping brand attitudes does not need to be considered in the development of brand identity. This brand-building block refers to the products and product characteristics you want potential customers to associate with your brand.

Block II.2: Brand Authority: If consumers are interested in a product category, they generally have some ideas about what brands they believe to be the quality leaders. And when they think about a certain brand, they ask themselves: What is this brand really good at? This brand identity element covers the ‘product scope’, ‘product uses’, and ‘competencies’ that you want your brand to be known for (Aaker, 2010; Kapferer, 2012).

Block II.3: Brand Qualities: Brand qualities cover the attributes and benefits that a brand wishes customers to associate with its products. What you would like your brand to represent may also depend on (1) your customer’s product evaluation criteria and (2) the product characteristics of your competitors. Brand qualities provide the basis for positioning.

Block II.4: Value Proposition: The value proposition outlines the most convincing reasons (key benefits) why target customers should purchase a particular brand/product. To differentiate from competitors, you can try, over time, to make your brand known for products that fulfil a specific key benefit. The value proposition is something each of your employees and customers should know about – therefore, it must be part of the brand identity.

Block III: Customers

When asked about their opinion about a certain brand, people often immediately describe the typical customer they have in mind (Keller, 2003). As a typical component of brand image, it must also be a major brand identity element.

Block III.5: Target Customers: Ideally, target customers refer to a specific niche segment. They are often not the same people who you want your customers to think would buy your products, but they are still part of the brand identity for these two reasons: First, thinking about a brand’s prototypical users without specifying its target customers beforehand almost always leads to confusion. Second, brand identity does not only refer to what you want customers to think about your brand, but also what you want your brand to be. Apart from segments that are unattractive in terms of economic criteria (e.g. purchasing power), you may want to stay away from customers who do not fit to your brand (vision, values, etc.).

Block III.6: Prototypical Users: This brand identity element describes the typical users who you want your customers to associate with your brand. A brand’s ‘prototypical user image’ refers to consumer perceptions about the users or buyers who seem to be addressed by the brand. Depending on their opinion about these perceived users (if actual clients or not), people more or less like or dislike this brand. Because this has a great impact on their business success, brands aim to influence their prototypical user image through brand communications. Porsche portrays in adverts men who are as young and dynamic as their actual 60+ customers would like to be again. The prototypical user represents the ideal (social) self of your core target customers – the person they would like to be.

Block III.7: Brand-related Self: The ‘brand-related (desired) self’ describes what you want your customers to feel and think to become when using your brand/products (Kapferer, 2012). Dove clients may feel being more beautiful and confident when using their creams. Connecting your brands/products with the life goals and desired self of your customers means that they can be used by your customers as means to achieve a higher end: to feel living their desired lifestyle and to become ‘who they really want to be.’ This brand element can help your brand to play an important role in the lives of your customers and can help you to connect your customers to a higher purpose (beyond the self), to achieve even ‘irrational loyalty’ (Tait, 2013).

Block IV: Brand Character

This is the core identity that characterises the ‘who’ behind a brand (also called ‘brand tonality’ by Esch, 2012). Given that consumers find it increasingly important to know who’s behind a brand, this brand-building block provides a key source for creating (symbolic) consumer benefits.

Block IV.8: Brand Culture: Every group of people develops a common subculture over time – and everybody is part of a culture or of different subcultures. So everybody does not only have a personal, but also a cultural identity. This should be reflected in the brand identity framework by having both: brand personality and brand culture. Facets of brand culture include place of origin, brand nationality, brand spirit, brand values, brand principles, and brand lifestyle. When you associate your brand with a subculture, you create brand meaning and inspiration. For instance, Ralph Lauren represents American aristocracy and Boston high society and WeSC (fashion) is rooted in skate-boarding. Brand culture creates the frame for brand personality.

Block IV.9: Brand Theme: Brands are constantly driven today to create new (social media) content to grow traffic and sales. But many brands just add noise by creating content for content’s sake. A brand theme is particularly useful to provide direction and meaning to a brand’s (social media) content marketing that it should be included in the brand identity model. It is an overarching idea that provides the foundation of your brand’s content strategy over the long term and can inspire the design of your marketing-mix instruments (posts, websites, adverts, events, stores, etc.). For Louis Vuitton, for instance, ‘travel’ has been a major inspiration since the brand’s beginnings in the 1800s.

Block IV.10: Public Face: When asked what they know about a certain brand, consumers typically come up also with people-related aspects, about the brand’s founders, owners, managers, designers, and other representatives. This brand identity element describes who is behind a brand. For instance, for many consumers it makes a difference whether this is a family business or some multinational corporate group. Given the desire of many people to establish trustworthy (business) relationships with real people, brands need to think about who they want their customers to see as the face of their brand. Many fashion designers or star chefs become the face of their business and develop into personal brands. However, every brand should cultivate at least one powerful personal brand from within the company.

Block IV.11: Brand Personality: Brand personality is so well-established and important for brand-building that it is included in all major identity models. A brand’s personality is often described by only a few personality traits such as decent, cheerful, or honest. To create a more meaningful, inspiring, and consistent brand, you can employ personality-driven branding strategies: (1) Describe your brand personality in sufficient detail to evoke a metaphoric mental picture about the person you want your brand to represent; do not just rely on personality traits, but also include demographics, life goals, motives, reference groups, etc.; (2) Imagine your brand to be a real person and keep her/him in mind for all type of branding decisions (about the design of a website, store, etc.).

Block V.12: Brand Relationships

This brand element is considered in most of the major brand identity frameworks (by Aaker (2010) and Esch (2017) as a subcategory of brand personality). The brand relationship block describes the mode of conduct and operation that a brand aims to establish with its target customers and other stakeholders. They impact the way a brand behaves, delivers services, and communicates with its clients. Companies like Uber created competitive advantages by disrupting the established relational roles in their industry (from driver/passenger to entrepreneur/supporter).

Block VI.13: Brand Touchpoints

Touchpoints generally refer to the principal stages customers pass through in their interaction with a brand. When people think about a brand, they also associate typical communication and distribution touchpoints with the brand (Keller, 2003). Therefore, touchpoints should also be considered in brand-building as a component of brand identity. Brand touchpoints describe for what type interaction and marketing channels a brand wants to be known for. For instance, to become an internationally renowned luxury house, brands need to develop concept stores in prestigious shopping streets such as Avenue Montaigne in Paris.

Block VII.14: Brand Expression

When you know what your brand should stand for, it is time to think about how to express that to its target groups (also referred to as ‘brand as a symbol’ by Aaker, 2010). For instance, Louis Vuitton uses the Monogram Canvas pattern to express its heritage and elegance (Esch, 2017). A brand’s identity can be expressed by brand design, communication, and behaviour. Brand design alone is a broad field of work including, for instance, the brand logo, layout, colors, and typography. Many companies still instruct an agency to develop their website without thinking first about what they actually want their brand to stand for. And many agencies still start with the brand design before laying the conceptual groundwork. The process of identity planning works like a structured creativity technique that delivers the creative input for brand design. A meaningful, inspiring, and consistent brand design is an expression of the great deal of thought and effort spent on the conceptual work.

This article was originally published on 22 March 2019.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Author

Klaus Heine is Associate Professor of Luxury Marketing at Emlyon business school, Asia and Co-Director of the High-end Brand Management Master Program at Asia Europe Business School in Shanghai. He holds a PhD from TU Berlin and specialises in high-end brand-building with applied-oriented research, education and practical projects with both, leading luxury brands and start-ups.

Klaus Heine is Associate Professor of Luxury Marketing at Emlyon business school, Asia and Co-Director of the High-end Brand Management Master Program at Asia Europe Business School in Shanghai. He holds a PhD from TU Berlin and specialises in high-end brand-building with applied-oriented research, education and practical projects with both, leading luxury brands and start-ups.

References

1. Aaker, D.A. (2010), Building Strong Brands, London, Simon & Schuster.

2. De Chernatony, L. (1999), Brand Management Through Narrowing the Gap Between Brand Identity and Brand Reputation. Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 15: 157-179.

3. Esch, F.-R. (2017), Strategie und Technik der Markenführung, 9th ed., Munich, Vahlen.

4. Heine, K. (2019) How to Build a High-end Brand. Upmarkit: Tallinn,https://upmarkit.com/brand-building-workbooks/how-to-build-a-high-end-brand”

5. Kapferer, J.N. (2012),.The New Strategic Brand Management, 4th ed., London, Kogan Page.

6. Keller, K. L. (2012`). Strategic Brand Management, Pearson: Edinburgh Gate, England.

7. Tait, B. (2013). The Mythic Status Brand Model: Blending Brain Science and Mythology to Create a New Brand Strategy Tool. Journal of Brand Strategy 1(4), 377-388.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)