In The Blue Line Imperative: What Managing for Value Really Means, Kevin Kaiser and S. David Young introduce a concept called ‘blue-line management’, an approach in which all decisions of consequence in an organisation are made with one aim: to create value.

Value creation and the ‘blue line’

It has become a truism in business that if value is to be created, a firm must systematically invest in those projects where the expected value of cash coming in is greater than the cash going out, a difference commonly expressed as Net Present Value (NPV). Projects with a positive NPV are value enhancing, while all other projects are value destroying. These values depend entirely on the cash flows expected from the investment in a probabilistic sense, and not on the cash flow forecasts made by managers. To put it another way, all investments have an intrinsic value that exists independently of management beliefs or assumptions.

The failure of confusing intrinsic value with personal estimates of value leads to the serious error of equating price and value. Price is the outcome of a market mechanism, or negotiation, between two or more parties. For any item, from consumer goods to shares of stock, the buyer in a voluntary exchange assigns a value at least as high as the price paid and the seller assigns it a value no greater than the price paid. The value of any company equals the present value of the expected future free cash flows discounted at the opportunity cost of capital and there is absolutely no reason to assume that the price negotiated between a buyer and a seller of this company’s shares is equal to this value.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

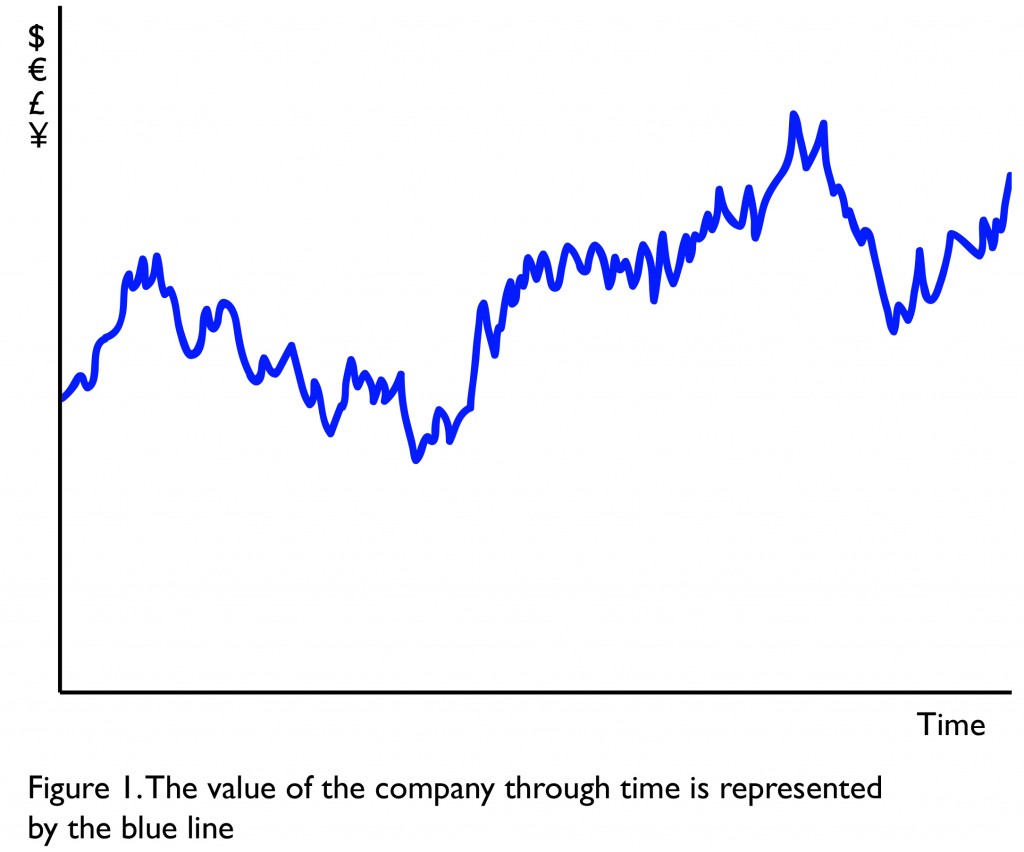

The blue line in Figure 1 illustrates how the intrinsic value of a company might fluctuate over time. Whenever expected cash flows or the opportunity cost of capital change, value changes too. For example, the blue line goes up every time the company invests in a positive NPV project. Seen in this light, the overarching goal of a value-driven enterprise can be expressed as follows: Raise the blue line as high as possible.

The obvious practical difficulty of this concept is that the blue line is unobservable. To know the intrinsic value of a company or capital investment proposal, one must accurately and instantaneously process all information about it, and know all states of nature that might prevail in the future and the precise probability of each potential state of nature actually occurring, and the cash flow consequences for these states of nature. Therefore, the intrinsic value of any asset is unobservable.

Price, on the other hand, arises from consensus forecasts of expected cash flows, not from the expected cash flows that drive intrinsic value. These consensus forecasts, and the probability distributions of future events implied by the forecasts, reflect the beliefs of many individuals. Although these forecasts may be reasonable estimates, they can never substitute for the true probability distribution that underlies value.

Despite the unobservable nature of the blue line, it still represents the goal for a value-driven entity. Indeed, the unobservable nature of the blue line is what makes value creation so difficult. In short, every decision either creates value or destroys it, independently of whether managers understand which is which. Of course, human nature being what it is, managers tend to focus on what they can directly observe. For this reason, companies everywhere rely extensively on a set of key performance indicators (KPIs). It is widely believed that by focusing management attention on observable and measurable KPIs, the business can incentivise value creating behaviour. This naïve belief has been responsible for staggering amounts of value destruction.

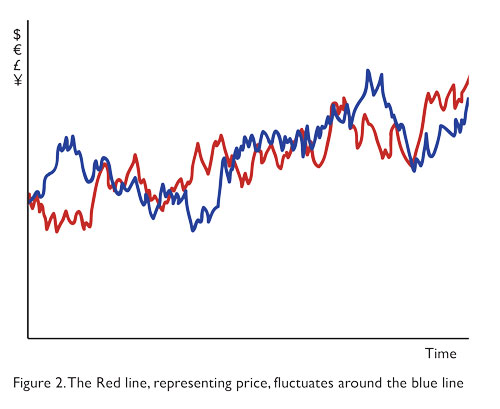

The most visible indicator of ‘value’ for a publicly traded company is share price. Indeed, value creation is sometimes expressed (erroneously) as a rising share price. But remember that share price is not value. It’s a market consensus of value, but under no circumstances should it be mistaken for the real thing. To clarify this point, consider the graph in Figure 2.

The red line depicts the movement of stock price over time. Although we cannot know this with absolute certainty, we expect the red line to fluctuate around the blue. As deviations between value and price get larger, savvy investors on the lookout for mispriced securities will take appropriate action. If shares appear seriously overpriced, they sell or even short; if the reverse is true, they buy. The practical effect of these actions is to tether share price to the blue line. The size of the tether that separates the two lines (i.e., the extent to which shares can be mispriced) is a function of market efficiency, how widely the shares are held, the number of analysts tracking the company, and so on. The extent of the mispricing, therefore, is likely to be far less for a global giant like Procter & Gamble than for a small biotechnology firm.

With this framing of price and value, we can now refer to ‘blue-line management’ as the approach that focuses on value creation as the overarching aim of the firm. We contrast this approach with ‘red-line management’ in which management focuses on performance indicators, such as share price, while ignoring the blue line. The stated goal may be value creation, but the practical reality is something else.

To summarise, while the two lines may never entirely coincide, when viewed over a sufficiently long time horizon, a high degree of convergence can be expected because of the ceaseless efforts by well-endowed investors to identify mispriced securities and profit from the mispricing. What this suggests is that the only way to be reasonably confident that share price will increase is to make decisions that raise the blue line. If a manager devotes time or other company resources to managing the red line, it is nearly certain that the diverted resources will cause the blue line to fall. This leads to the interesting result that trying to manage the red line with the aim of raising share price will almost certainly result in a lower share price. In contrast, a blue-line company never tries to ‘manage’ its share price. Instead, it simply allows price to be determined by the capital market. To put it another way, a higher share price is the reward for good management, not the goal.

Share price isn’t the only contestant for red line management. Within all modern organisations, the increasing access to data enables managers to track myriad metrics that indicate the relative performance of different elements of their business. Each and all of these metrics could become the focus of any individual or team within the organisation. In fact, once someone realises that the metric is being used to assess and measure their performance, even if the person isn’t being compensated directly based upon the metric, it will still be extremely difficult for this person to not begin to manage the metric in order to make their perceived, measured, performance look better. Unfortunately, these ‘red lines’ are no more value than is share price. It is very conceivable, even easy, to increase earnings in a given period in a way that destroys value. The order of cause and effect is very important.

The dangers of indicator-based pay

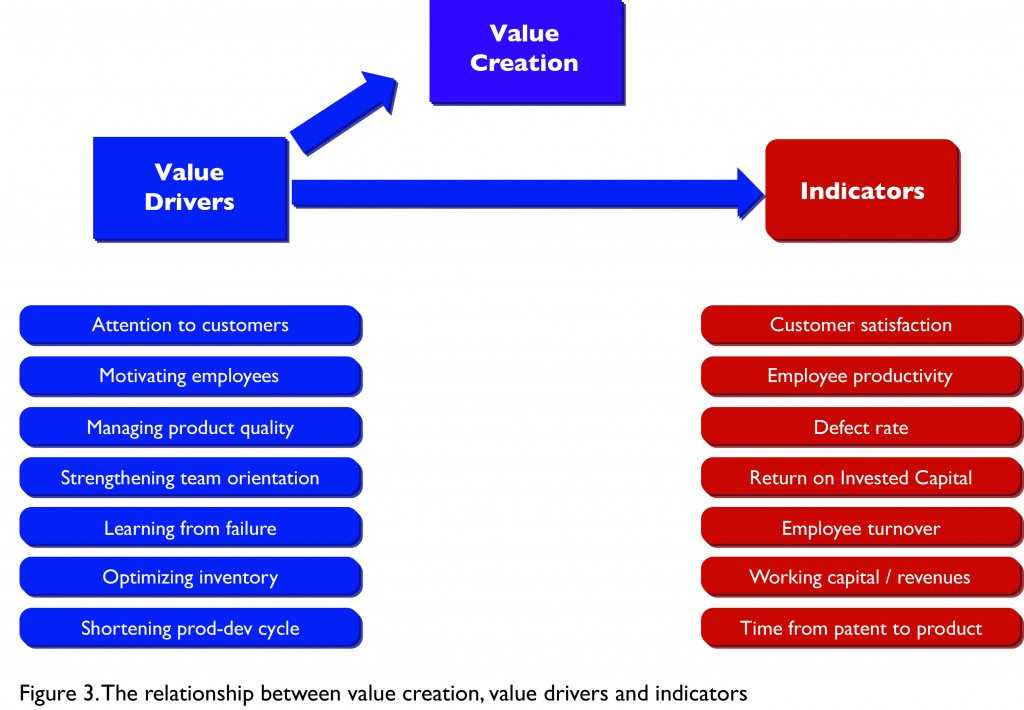

At corporate level, much of red-line behaviour is motivated by the desire of senior managers to finesse share price. However, similar thinking can occur at any level of an organisation, principally through the misuse of KPIs. As shown in Figure 3, the objective of value creation is achieved though actions and behaviours commonly known as value drivers. These drivers are the behaviours and actions that truly drive business success. Examples include motivating employees, relationships with customers and suppliers, the positioning of equipment and machinery in factories, and so on.

Because the actions and behaviours related to value drivers are not directly measurable, companies rely instead on KPIs. Indicators are the observable results of behaviours, after the influence of myriad random factors that arise between business decisions and their outcomes. Indicators are, at best, noisy indicators of how well value drivers are being managed. For this reason, an indicator should never be mistaken for a value driver, just as we must never confuse share price with intrinsic value.

Evidence of red-line management will show up in a number of ways. First, people will have their integrity challenged when they are forced to decide between putting value first, or taking short-term oriented, KPI-driven decisions in order to advance their career and personal interests. Second, top management will cascade KPI targets throughout the organisation in the hope that if business units deliver on their targets, top managers will achieve desired KPI targets at the corporate level.

An additional concern when indicators are used for incentives is that the indicators will no longer indicate what managers think they are indicating. Instead, they become contaminated by the conscious efforts of decision makers to manage them. What are already noisy proxies for value drivers become even noisier, and their use in diagnosing genuine problems or knowledge gaps is seriously compromised.

As everyone in the organisation manages to KPIs, it becomes impossible to trust the indicators or to interpret them in a meaningful way. Managers will therefore be unable to understand how changes in behaviour impact either outcomes or value creation. Given the inherent difficulty in distinguishing positive NPV projects from negative NPV, even in the best of circumstances, value creation becomes a practical impossibility because all numbers are lies to varying degrees.

In addition, as employees are incentivised to deliver on specific indicators, and thus begin to manage the indicators, they quickly realise that they no longer have a shared, or aligned, purpose. They realise that whatever the stated purpose of the organisation may be, it is not value creation. Indeed, even when senior managers insist that they are still focused on value and wish everyone else in the organisation to do likewise, middle managers understand that they are being paid to deliver on indicators independent of value creation. In either case, employees will lose sight of their common purpose. Alignment is lost and people no longer work toward the same objective.

Eventually, the best people (i.e., those with the greatest value-creating potential) will begin to leave the organisation if it continues with a red line approach to management. Why? As we alluded to above, awareness of value is deep and instinctive in the human brain. The reason concerns the simple, but subtle, concept known as the opportunity cost of capital. The word ‘capital’ refers to resources, which, at the end of the day, means ‘energy’. In evolution, energy is always in short supply and only those species able to adapt to an ever-changing environment in order to access and utilise efficiently the energy needed to sustain life will survive. Whenever energy is used for one pursuit, it cannot simultaneously be used for an alternative pursuit – this is the opportunity cost of energy. Humans are instinctively aware that a use of energy which does not sustain the health of the ‘team’–in the days of our distant ancestors, ‘team’ would have referred to the tribe to which a human belonged, in modern times it refers to a family or a business or a country–is not a desirable use of energy unless it delivers more utility or happiness than alternative uses of the same energy might have delivered. This is captured in the NPV concept, which reflects both the happiness delivered (as the future free cash flows returned back to the company from the customers who were made happier by the product or service delivered) and the opportunity cost of the resources used to deliver the products and services. Because of the instinctive nature of this concept, all humans in all cultures (with or without finance training) will have a strong sense (think of it as an internal ‘value-meter’) of when value is being created or destroyed.

This internal value-meter is tightly connected to their internal ‘fairness-meter’, because in evolutionary development, those who destroyed the tribe’s value (used the scarce energy inefficiently) would have faced consequences in the form of punishment or banishment. This would have restored the evolutionary sense of fairness. In modern organisations, this evolutionary fairness is the main driver of a decline in morale. When red line management results in some members of the team being promoted even though they destroyed value (for example, in order to deliver on a growth target) the other members of the team will quickly sense unfairness. Eventually, those unwilling to participate in such unfairness will either leave, or they will stay but become increasingly disgruntled. They will then withhold their own energy and simply show up for work, ceasing to contribute in a meaningful way.

A blue-line approach to the use of KPIs

The primary function of KPIs in a value-driven business is to promote organisational learning, a mission that will almost certainly be undermined when indicators are used for incentives.

Value creation is ultimately about how we manage ignorance. In an uncertain, complex world, the successful business culture is one in which everyone is continuously learning. It is also a culture in which having the right answers is less important than asking the right questions. In other words, value creation demands experimentation. In a value-based culture, not only is trial-and-error tolerated, it is strongly encouraged. Such a culture cannot possibly prevail if managers are forced to obsess about outcomes.

When set honestly, targets are useful hypotheses about how business systems are supposed to work. They reflect expectations based on imperfect knowledge. The actual outcomes for KPIs will then reveal the extent to which our understanding of the system was incorrect or incomplete. In effect, indicators act as early warning signals, the proverbial ‘canary in the mine shaft’. The surprises that inevitably result from the discrepancies between targets and outcomes reveal problems as they emerge; allowing us to plug knowledge gaps and resolve problems faster. But this process works only if we allow it to. When businesses are managed on KPI outcomes, the problems that might otherwise be revealed are suppressed, hidden, and ignored.

Performance measurement systems must reveal the truth

Great swathes of wealth have been destroyed because of a common tendency among business executives to confuse value and share price, and to believe that achieving KPI targets is tantamount to value creation. Shareholder value does not come from a higher share price, but from positive NPV investments and other actions that raise the firm’s blue line.

Similarly, delivering on KPI targets is no guarantee of value creation. When managers have incentives to manage to the indicators, the indicators no longer represent what they are supposed to represent. Sales growth and profit margins, for example, are undeniably important indicators, but how can we interpret them when we know that, to some extent, they’re lies? KPIs are indispensable to organisational learning, but this critical function can work only if the performance measurement system is designed to reveal the truth.

Download the digital edition of The European Business Review from Zinio.

About the Authurs

Kevin Kaiser if Professor of Management Practice at INSEAD. He directs and teaches in many corporate executive programs for INSEAD, he also teaches in numerous institutes and for private clients throughout the world. He holds a PhD from Northwestern University and is a former consultant with McKinsey & Company, where he led a variety of studies addressing value creation and corporate strategy.

S. David Young is Professor of Accounting & Control at INSEAD, where he teaches in the MBA program and in a broad range of executive courses. He has served as an advisor to companies in the U.S., Europe and Asia on various aspects of value-based management and is also a frequent advisor to investment firms on the analysis of corporate accounts. He holds a PhD from the University of Virginia.