By Guido Stein and Kandarp Mehta

In every professional’s journey, there are those defining moments which can change one’s entire career. In this article, the authors elaborate not only the strategies involved in job offer negotiations, but more importantly, how the art of negotiation can significantly jumpstart your entire professional life.

An Approach to Driving Negotiations

Experience and research teach us that there tends to be a lot of room for improvement when it comes to approaching the negotiations that take place during the hiring process. Numerous studies have demonstrated that successfully negotiating for a first job has very significant consequences later on in the candidate’s career – for example, in economic terms or in terms of speed of promotion. Research has shown that candidates who try to negotiate their first job offer can potentially add an additional $1,000,000 of value to their overall career during the next 25 years.1 Likewise, companies could get what they need more effectively if they took into account the relevant factors in this type of negotiation and if they took suitable advantage of the different phases the processes go through. Although every situation is different, the idea is to create a win-win situation, so everyone’s needs are met, without necessarily implying a loss for the other party. There lies the art of negotiation, since people tend to walk away with less than they could have received.

No one doubts that a job is much more than the salary that can be earned in it or paid for it. However, people’s actions are not always in line with this obvious fact. The reason is that what is obvious is not, in fact, the first thing that catches our attention. More than money is at stake for the potential employee and employer. The former brings to the table a significant portion of his or her life; the latter offers up part of the company’s ability to compete and survive – in short, whether the company is able to fulfil the purpose for which it exists. For the candidate, the necessary condition is to be wanted, to convince the company he or she is the best choice. The rest will come later.

If one of the parties or both make a mistake in the selection and, later, in putting that selection into effect, from that moment on there is not much that can be done. The first principle is not to waste time – your own or other people’s: if the offer does not meet the candidate’s basic demands or the candidate does not have the key characteristics of the profile the company is looking for, it is better to be realistic and to avoid settling for half measures.

On the other hand, once the decision has been made to move on with the process, a negotiation phase begins that may (or may not) be a source for the mutual creation of value and opportunities, with the associated consequences. We must accept that any negotiation implies certain risk. Negotiating a job offer is mainly a chance for the parties to get to know one another, while laying the groundwork for a relationship that will continue over time – in some cases for many years. Experience and research both show that around 90% of companies expect candidates to be prepared to negotiate, whereas in reality only 25% of them actually do so and only about 15% of employees who are hired then renegotiate their employment conditions after some time has passed. That means there is a high probability that employees who remain loyal to their companies will end up being below the market average in terms of salary.

The personal image transmitted by a candidate who negotiates is better than that of one who does not negotiate, so long as this behaviour is not a deterrent for the employer because it leads to the employer no longer liking the candidate or being put off. The best negotiations originate in a shared knowledge of what is important to both parties, who overcome their ostensible differences and thus work toward the harmonisation of interests and capabilities. This involves not only or mainly the role of negotiator but also the role of fellow explorer travelling through unknown territory. It is worth investing in revamping the stereotypical model of a classic job-offer negotiation. In that sense, it is enough for the parties to put a bit of effort into replacing haggling with intelligent exploration.

It is a good idea to avoid the bias that leads negotiators to draw conclusions about the other party’s future behaviour based on their own fears or uncertainties.

First impressions leave a near-permanent mark, since the candidate uses them to glean information about how he or she will be treated during a regular workday at the company. Negative experiences are often created (inconsiderate or high-handed treatment, pressure regarding salary terms, slowness in providing information, etc.), which could have been avoided without harming in the least the company’s position in the negotiations.

Being an effective negotiator does not boil down only to knowing how to negotiate but also when to do so. In some situations, negotiating may not be the best option: for example, when the best alternative to continuing negotiations is unfavourable and obvious, or when it is much better than the best offer the other party might propose;2 when negotiating sends a message that would be misinterpreted or misunderstood by the other party; when the harm caused to the relationship by negotiating is worse than the supposed advantages and, as such, it endangers future negotiations; when the other party does not expect negotiations to continue, etc.

As such, sometimes it is better to accept the financial offer without any further negotiation. The idea is that, after a certain time, a more favourable atmosphere will be created for discussing improvements, which will be supported by actions that confirm the candidate’s value and by greater receptiveness on the part of the employer. Knowing when to wait is an effective negotiating tool.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

The Question of Salary During Negotiations

Often, employers will ask candidates about their current salary, or what they earned in their last job. Why is that? For a number of reasons: finding out what kind of salary they should offer the candidate if he or she is selected, seeing the discrepancies between what they are offering and what other candidates are earning, etc. The truth is that people on higher salaries tend to be perceived as performing better and, inversely, people who have lower salaries are usually assumed to be less good at their jobs. However, that does not account for the explanation for this difference: for example, if two professionals begin working at the same time at the same company and one of them negotiates a salary deal but the other does not, the difference persists due to inertia.

If a professional wants something an employer is not offering, he or she needs to think about the most effective way to let the employer know. What people earn tends to depend on what they contribute, their professional value and how well they negotiate based on that value.

When should the salary be discussed? From the candidate’s point of view, in general, later is better than sooner. The more time a candidate invests in a company, in theory, the more committed he or she will feel. The best bet is to wait for an offer, since it is preferable for the employer to be the one to name the first number, given that this effectively serves as the foundation to build up from. Likewise, it gives the candidate an idea of what the company is willing to pay and thus limits the risk of going above or below that mark in the case of the candidate naming the first figure.

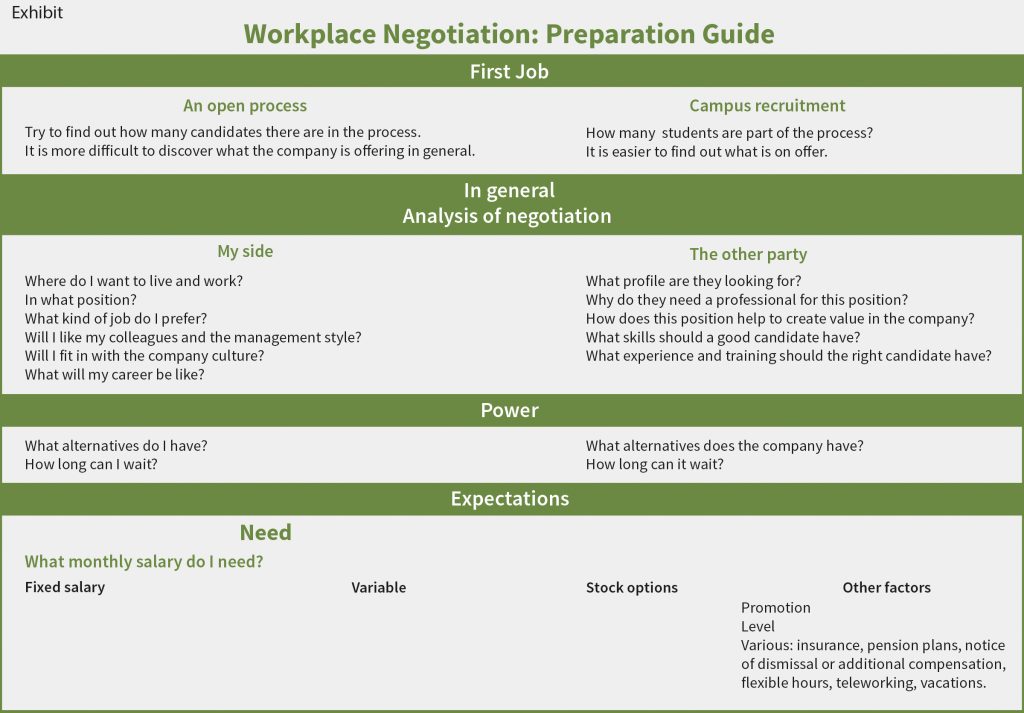

Experience has shown that, sometimes, when MBA students are having their first job interviews and are faced with the question about their salary expectations, they tend to make two fundamental mistakes: they either lie or they try to avoid the question. A job interview is a conversation, and any conversation has to be fluid if the participants are to achieve their goals. Bypassing a question cuts off the flow and, in turn, the desired effects of the conversation. So, rather than avoiding the question, it is better to understand it. To gauge the scope of the question, there are two important things to be aware of: 1) How will the possible answers affect my position in the negotiation? and 2) Why is the interviewer interested in this information? Often, thinking about these two aspects on the spur of the moment can be hard. That is why it is useful to prepare your responses to these questions ahead of time. In the Exhibit, a preparation guide for salary negotiations is suggested.

In some cases, instead of providing a rough salary range, the company representatives, especially people from the Human Resource Department, may ask candidates what they hope to earn or what they are currently earning. If that happens, it may make sense to respond with statements such as: “Money isn’t the most important factor in my decision”; “I’d like to know more about the job’s requirements and the company’s priorities so I can think about what contributions I can make”; “In principle, I’ll accept any reasonable offer”; or “What would you normally pay someone in a similar position?” Ultimately, the goal is to gather more information in order to come up with an appropriate number.

If the company insists that the candidates give a precise answer, they must be able to provide a number that is supported by objective arguments, such as what the market offers, on average, for a similar profile; what is paid at the company as far as they are aware; and what they feel they are worth based on what they can contribute to the company and on their level of experience. It is a good idea to leave open the possibility of discussing this factor in more detail along with other aspects of the job, such as just what the position entails, the level of responsibility, the possibilities for advancement, the flexibility of work schedules and vacation time, training, etc.

Beth, one of our MBA students once had an interesting experience. Her potential employer asked her what her salary expectations were and she did not give a precise number. In turn, the company made an offer that was extremely low, not just compared to her expectations but also by normal salary standards of fresh MBA students from our institution. She was upset and was thinking of writing a very angry email to the company. However, we took a different approach. We asked her to explain to the organisation that the salary was very low and support her arguments with different statistical information. She wrote a very polite email where she showed the average salary of MBA students from premier institutions as well as average salaries offered to students with her profile. The company responded back with a very positive response, stating that they were creating a new position and they had never hired an MBA from a premier institution with her kind of background, and promised to revise their offer. Eventually Beth received an offer that was almost 60% percent higher than her original offer and the company was also happy to have received a bright and happy employee.

How Should You Approach a Job Interview?

Help Them Help You

If we look at the example of Beth we can realise that what really helped her was her initiative to help the organisation. Following, in part, the ideas of Deepak Malhotra,3 the main goal of a job interview is for the company to want to meet with the candidate again because they liked him or her, they were pleasantly surprised or because he or she is a good fit. The better the impression left by the candidate, the stronger his or her negotiating position will be. It is enough for the candidate to avoid anything that the other party might not like, such as having an untimely, unjustified or excessive interest in the economic component, being petty about small details, or being needlessly impatient.

Arrogance is lethal, although it is possible to temper it and change it into healthy ambition through justification, based on objective references, of why you deserve what you are going to end up asking for further on in the process. The reason why any candidates are asking for more must be based on them truly deserving it, which will not make them disagreeable. If this foundation is lacking, it can be prudent to wait before expressing this kind of demand.

Understanding the Other Parties: Sharing Their Criteria and Constraints

Let’s think for a moment of the example of Beth again. Her potential employer took pains to understand what Beth wanted to express. Negotiating is an activity between people who do not always behave as they should or as we would expect. The employer in this case tried to understand the point of view of the candidate and it helped them create a very positive dialogue. On the other hand candidates do not face the same situation if, instead of negotiating with the person who will be their boss, they do so with a representative of the Human Resources Department, as has been noted already, since they do not use the same criteria 100%, (the feeling of urgency may be different for the boss than for the head of human resources) nor do they attach the same priority to those criteria that they do share (for the boss, the question of remuneration tends to be less of a limiting factor than for human resources).

All negotiators have two types of interest: those of the company or the department they represent, and personal interests, something that candidates must bear in mind according to the change of interlocutor, which will make their expectations more realistic and expand the negotiating options, as well as the possibilities of dealing with obstacles that may arise.

Once the firm likes and wants to hire the candidate, it is possible that the company will be unable to offer what he or she asks for. The candidate has to find out, before beginning the process or during the first conversations, what the real limitations of the interlocutors are in the matters that interest him or her (fixed and variable compensation, nature of the position, reporting level, promotion options, flexible working hours, training, relocation, insurance, allowances, etc.). The more that these factors are known, the better a position the candidate will be in to deal with them to the satisfaction of both parties.

To do this, it is useful to draw up a list of the needs of both parties (whether these have been made explicit or not; in the latter case, the list would be based on approximations and plausible hypotheses that should then be verified through conversations and research) and to put these in order of priority (using the same tools mentioned) in order, finally, to reconcile them as far as possible.

The VIA (vital, important and additional) framework enables the needs to be put in order and packaged to be prepared for the purpose of carrying out exchanges through value creation for both parties. The parties rarely have two vital needs in confrontation but, in such a case, an obstacle would emerge.

The Trees Are Not the Whole Forest

Negotiating a job offer goes far beyond money, since life is not about material things alone. For this reason, it is necessary not to lose sight of the fact that it is a multifactorial negotiation, not just for today but with consequences for the future – that is, not only is there more than one “what” but, in addition, the “how” and the “when” can be essential sources of value creation for both parties.

Not losing sight of all the pieces of the puzzle regarding what both parties can get from the negotiation enables a flexible attitude and prevents one from being blinded – that is, being trapped by one or several matters that might involve conflicted interests. It is also advisable to deal with them at the same time and not successively, one by one, since in this way packages can be prepared for deals that will add up to a positive result for the employer and for the candidate and avoid one gaining at the cost of the other losing out.

Continually haggling for a little bit more will end up annoying the other party, which will not help make them generous with whatever the candidate might ask for in the future, just the reverse: it will limit that party’s desire to negotiate and to create value together. A workplace relationship can be expected to have a future, unless the relationship ends in a break-up, which can be caused by a negotiation whose result is very unbalanced for one of the parties.

Anchoring in the Negotiation

Furthermore, it should be noted that whoever speaks first, if they do it well, anchors the process in their favour. Academic research into the impact of anchoring has confirmed time and again that, in negotiations, it plays a decisive role. A negotiator who sets out a more ambitious first offer than other negotiators always ends up getting more than the others. Nevertheless, being determined to declare yourself first entails two risks: first, the counterparty will lose interest in continuing to negotiate, simply because the base or lower limit seems unachievable to them and, second, that the offer, because it is ambitious, will not seem credible. In salary negotiations, it is always necessary to be prudent when answering the question “What are your salary expectations?” One strategy for tackling this question consists of answering in ranges. Research in experimental psychology has shown that negotiating in ranges leads to a stronger anchor. For example, instead of answering “my salary expectation is €40,000 a year,” it is preferable to opt for “applicants of my profile in the market, from what I have observed, make between €40,000 and €42,000 a year”. So, negotiating in ranges brings a series of advantages, such as that of establishing a double anchor4 that will make it more likely that the counterparty will end up coming closer to our expectation. Another advantage would be that of keeping the dialogue open. Talking in ranges and justifying the range not only protects interviewees from the risks of unjustifiable offers but also invites the other party to explore the reasons for this range and therefore this provides interviewees with an opportunity to explain their expectations better.

It’s Not Personal – It’s Negotiation

There is a series of direct questions that increase the competitive temperature in a negotiating process, such as “What is your current salary?” “Have you had other offers?” “Where are you looking?” “How long have you been looking?” “Are you changing companies because of the money?” and “Could you start right away?”

The same thing happens with pressure or ultimatums along the lines of “take it or leave it,” “we can’t go beyond this limit,” “you have to answer within 24 hours or you’re out” and similar. In these contexts, it is essential to react calmly and professionally. Fundamentally, they are providing information that should be decoded correctly and, to do this, it is necessary to understand the constraints, concerns and needs of the speakers: Why are they doing this? What do they really want?

Generally, these constraints indicate that the company is still interested in the candidate and how he or she reacts. They also demonstrate how the employer processes the uncertainty typical of the negotiating process and that it wants to clear up doubts or gain negotiating power in order to enjoy a more comfortable position. There is rarely an underlying personal issue or desire to annoy. The negotiation is taking place in all its splendour: the best thing to do is focus on the details, keep calm and enjoy the challenge.

When faced with a threat or ultimatum, the most sensible reaction is to attach no great significance to it and not insist that they confirm what was said. This way, whoever issued the statement will be less disposed to act on it or will be more able or willing to withdraw it. Helping out the interlocutor can provide a foundation for value creation, conflict resolution and the overcoming of obstacles. The key lies, once again, in investigating what is behind the threat because, if it is real, it will come up again.

In short, negotiating effectively requires managing expectations wisely in conditions of uncertainty, by way of an inquisitive approach focused on the underlying interests of both parties.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Guido Stein is Academic Director of the Executive MBA of Madrid, Professor at IESE Business School in the Department of Managing People in Organizations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance).

Guido Stein is Academic Director of the Executive MBA of Madrid, Professor at IESE Business School in the Department of Managing People in Organizations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance).

Kandarp Mehta is a PhD from IESE Business School, Barcelona. He has been with the Entrepre-neurship Department at IESE since October 2009. His research has focussed on creativity in organisations and negotiations. He frequently works as consultant with startups on issues related to Innovation and Creativity.

Kandarp Mehta is a PhD from IESE Business School, Barcelona. He has been with the Entrepre-neurship Department at IESE since October 2009. His research has focussed on creativity in organisations and negotiations. He frequently works as consultant with startups on issues related to Innovation and Creativity.

References

1. Thompson, Leigh, 2014, THE MIND AND HEART OF NEGOTIATOR

2. When there is no zone of possible agreement (ZOPA), the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) should be put into play.

3. Malhotra, D., “15 Rules for Negotiating a Job Offer,” Harvard Business Review, 92(4) (April 2014), pp. 117–120.

4. Ames, D., and M. Mason, “Tandem Anchoring: Informational and Politeness Effects of Range Offers in Social Exchange,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(2) (February 2015), pp. 254–274.