How far is too far in gleaning user data and handing this over to advertisers, even though the aim is to continue to provide a valuable but free user experience?

Social media companies, especially the dominant platforms like Facebook and Google, have understood from day one that their underlying business models worked only if they could strike and sustain a very delicate balance. Most of their users pay no fees but still expect their user experience to be ever more valuable, rich, and personalised. The money, of course, comes from advertisers, who pay for ever-more focused access to these users. The reason is obvious: it amply pays them to do so. Facebook reported $14.27 billion in ad revenues for 2015; Google, more than $60 billion. What links the two halves of this equation are the robust algorithms that derive monetisable insight from the information that is supplied by users and, more importantly, generated by their click streams on site.

Within the evolving constraints imposed by privacy laws and regulations, the challenge has always been to use such insight to improve user experience enough that no one really minded what advertisers knew or did with their knowledge. Accordingly, the art has been to know, with some precision, precisely where and how to identify the tipping point – the Putin balancing point, if you will – up to which individuals are willing to give up certain social protections in return for promises of improved benefit or experience.

This is the delicate balance that is now under threat. Part of this threat is explicit, visible, and familiar. As newspapers regularly report, there is a rising level of social discomfort with the very fact of a Putin balance in the first place, no matter what the benefit – that is, with the stony reality that third-party advertisers ‘out there’ can now know so much about me in such minute detail from so many sources that my privacy is irreparably compromised. Understandably, much research is now devoted to understanding, for different user segments, just how far such discomfort has already spread and what choices it is likely to prompt.

But there is also a part of the threat that is more subtle and much harder to see, but perhaps even more disruptive and dangerous. The challenge it poses is not so much to advertisers and the fees they pay to social media companies, as it is to the internal operations of the social media companies themselves. It did not emerge, gradually, from slow, easily trackable changes in social attitudes and preferences, but rapidly from quick recent improvements in data analytics and the technologies that support them. It is also possible to purchase YouTube views. And although there are well-developed streams of research relevant to understanding it, they have not yet been urgently brought to bear on these specific challenges.

As user communities grow in size and user activity increases in volume, the digital footprints left behind generate ever-better data that, in turn, social media companies use to personalise the kind of content specific users see, as well as the order in which they see it. This filtering is essential. Without it, users would be so inundated with content that their online experience would be, at best, confusing and, more likely, unpleasant. As a practical matter, the choices implicit in such filtering for so many people are not – and cannot be – made by live humans. They are instead created by proprietary algorithms that users never see and of which they are largely unaware. This, too, is part of the Putin balance. When it works, users are sufficiently pleased with the personalised flow of content that reaches them that they do not much concern themselves with the unseen algorithms that control it.

It is no surprise, therefore, that social media firms focus much of their effort on improving these algorithms and the user experience they support. This is not new. What is new is the degree to which the data requirements and algorithms of paying advertisers have silently begun to shape, without warning or notice, not just their own ad-related choices, but also the algorithms used to determine the broad range of non-ad-related content that flows to users. Yes, these developments may add a bit to the personalisation of these flows. But they do so in ways that primarily serve the agendas of third parties, not the users themselves.

What is only now becoming clear is that this more general, growing, but still hidden reliance on ad-driven algorithms risks upsetting the Putin balance entirely, along with the established business models it supports. There is a fine line that separates the positive experience of being personally served from the very negative experience of being stalked. Once that line is crossed, all bets are off.

A Facebook Moment

A few months ago, I took a break at a Starbucks outlet on HuahaiLu in Shanghai. It was a cold and rainy day, and a hot chocolate sounded like a very good idea. It was mid-afternoon, and Starbucks’ free ChinaNet access allowed me to use a VPN server to reach my Facebook home page. As I opened it, I noticed in my newsfeeds a promotion for The Economist magazine: a subscription offer for CN¥88 and a free copy of “The World of 2016”. According to the feed, two named friends (former students who are in my contact list) and 14 others “like” The Economist. When I clicked on the “14 others”, I got a list of another 14 names from my contact list.

Evidently, Facebook knew that I was in China (quoting the offer in Chinese RMB), that I regularly read articles in The Economist, and that I currently have no subscription to the magazine. Obviously, I was a good target. But how did they come to know all this? And what else did they know? More importantly, did my being on this radar screen have other implications? How would I know?

I was also concerned by the presentation of the native ad. True, seeing the names of some of my contacts made the ad look personal, but it also raised a host of questions. Did these friends know their names were being used in this way? Equally worrisome, was my name being linked in the same fashion to offers being made without my knowledge to others in my contact list? These concerns made me uneasy.

The promotional offer itself came to me with 3 “likes” and one comment. When I opened the comment, it listed the name of a person who was unknown to me and who was not in my Facebook contact list. The comment by that unknown person read: “Best coverage of modern China”. As the former dean of a major business school in Shanghai and quite knowledgeable about China, I found the comment somewhat lacking in credibility. Why would they think I’d accept it at face value? This nagged at me, and so I decided to dig a little deeper.

The unknown person who made the comment had a Facebook page of his own, which featured a vintage-looking picture of a young boy with, presumably, his father, on a beach somewhere. According to his profile, that person grew up in Queens and visited China in 2013. When I searched the Facebook directory, I found the name of that person listed in several different places, each with a slightly different spelling. All those listings had accompanying pictures, but they did not look like pictures of the same person.

When I checked the 3 “likes”, the unknown comment maker was there, along with two other names: one an Arabic name and the other “Jim Justice”. The profile page of the person with the Arabic name was suspiciously sparse, indicating only that the person was based in Shanghai. This was possible, of course, but it made me wonder if that name had been triggered by the fact that I am currently based in Beirut and, therefore, have many Arabic colleagues listed among my contacts. “Jim Justice” has only a picture on his Facebook page with no profile details and no entries. But the person in the picture looked surprisingly like a former colleague of mine whose name is neither Jim nor Justice.

This whole experience left me distinctively uncomfortable. The Economist offer was appropriate and timely, but the supporting feeds struck me as disingenuous. The platform knew enough about me to cobble together information that, on the surface, seemed plausible but, on closer examination, seemed fake and manipulative. The algorithm-based relevance of the ad heightened my expectations about what to expect. Therefore, when the collateral feeds did not meet those expectations, they backfired. The experience they left me with did not make me feel better informed or supported by a community of my chosen peers. It made me feel stalked.

A Two-Edged Sword

Twenty years ago, even ten, the data sets and algorithms for highly-customised ad targeting were much less finely developed than they are today. The flow of messages we received was – and was largely expected to be – broadcast and generic, not carefully personalised. Advances in technology and data analytics have now raised our expectations. We have come to expect such personalisation, and advertisers have repeatedly done the math to prove that the mutual benefits of such personalisation are well worth the investment. Within reason, these changes do not need to tip the Putin balance.

But if I as a user come to feel that these technology-enabled advances do not really serve my interests, that they are driven primarily by the agendas of others, and that my growing expectations of being better served are undercut in practice by the unwelcome experience of being stalked, I may well react against them with surprising speed and force. If I do and if many others do as well, this will indeed tip the balance – with force and speed.

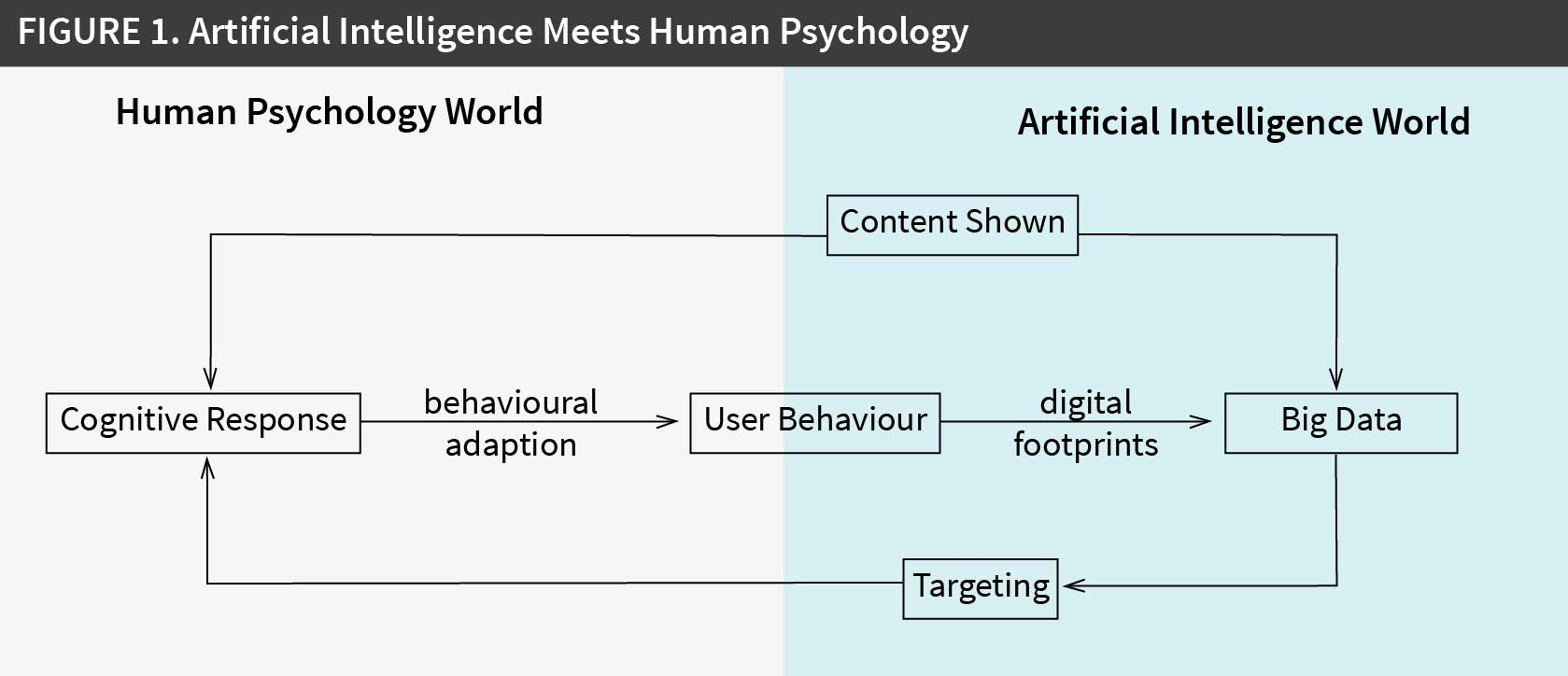

As cognitive research clearly shows, such changes in expectation are a two-edged sword. Figure 1 (see figure 1 below) shows how user behaviour shapes platform behaviour (or, more specifically, the algorithms those platforms use), and how the latter in turn affect user behaviour through cognitive responses that lead to behavioural adaptations. In the “artificial intelligence world” (the right side of the graph), the digital footprints of user behaviour give rise to what is now commonly referred to as Big Data, which drives algorithms that perform two tasks: personalised ad targeting (making sure the right user gets exposed to the right ad at the right time) and content feed selection (what the user sees when logging into the platform: eg, search results in Google or news feeds in Facebook). Both of these tasks trigger cognitive responses in users.

The cognitive response to personalised ad targeting can, of course, be positive or negative. If targeting is successful, users will get more involved with the ad. So, if the ad makes a compelling argument, a positive response becomes significantly more likely. But if the ad is weak or, worse, is perceived as manipulative, the likelihood and even the strength of a negative response can escalate every bit as quickly. This phenomenon of elaboration is well established in the consumer behaviour literature. As targeting algorithms improve, changes in user expectation cause the performance threshold for ad effectiveness to go up in parallel, thereby magnifying the potential negative effects of user discomfort or irritation.

Future-Proofing Targeting

The technology of ad targeting will, of course, not go away – and will almost certainly get more sophisticated over time. It will increasingly be expected to deliver ads that targeted users find credible, compelling, customised, reassuring, and appropriate to time and context. It will be expected to empower users to be part of the experience through interactive engagement. (Just think, for example, of the conversational ads with which Twitter has been experimenting). And it will be expected to deliver messages that “fit” and feel appropriate, even when configured like Swiss Army knives for effective use at the time of exposure. But it will do none of this if what actually gets delivered is not trusted – or, worse, undercuts the willingness of users to trust at all. And as noted above, as the ability to target and customise rises, so does the threshold for trust – that is, the level of expectation about what a properly personalised experience feels like. It may be obvious but bears repeating: those who feel stalked do not trust. Period.

That is why, as ad technology improves, it becomes ever more urgent for social media firms to refocus on users in ways that support their trust by alleviating or, better, preventing any perception of their being stalked. That means being more transparent about how the algorithms in use affect the curation of the content feeds that flow to users. It means enabling users to participate in those curation decisions by making those choices visible and then giving users some say over who can target them, when, and for what. And it means allowing users to share in the fees advertisers pay to use their data to target them better. None of this will be easy or comfortable. All of it threatens, to some degree, the business model currently in place. But, like it or not, it is the price that has to be paid to sustain trust. Far better to do some unwelcome repair than let the whole building crumble.

The good news, however, is that such repair need not be only painful. It may be able to improve outcomes and experience all around. With content-feed search algorithms, for example, users often have lots of useful information to contribute about what they most want and need, when, and in what form. Rather than automatically rely just on their past click-stream behaviours across a varied range of searches, why not directly involve them in identifying the kinds of things that are most important to them when doing those searches? What specific users want when looking for the French word for mobile phone is likely to be different than the inspiration they seek when looking for an adventure trip for the family. Why not make this transparent? Why not ask them? Why not get them involved? There is, after all, plenty of research that shows that the experience of co-creation can be a powerful engine for building the engagement and personalisation that, in turn, builds trust.

A LinkedIn Moment

Since my experience with The Economist offer on Facebook, I pay more attention to the ads in my newsfeeds. I seem to be getting more of them than I previously thought I did. A few weeks back, I found an ad for The NY Times in my Facebook newsfeed that offered, for that weekend only, 8 weeks of free digital access. The idea was appealing, but the format of the offer was exactly the same as the one from The Economist discussed above: two named contacts together with 12 others who “liked” The NY Times. Feeling stalked, I did not check further.

More recently, I received a weekly e-mail from the Coca-Cola Refreshment LinkedIn group, for which I had signed up a while ago. At the time I did, I had been given options on when they could alert me. The fact that I had been given that choice made me feel positive, even welcoming, toward the new message when it arrived. Such are the seeds of trust.

About the Author

Dr. Wilfried Vanhonacker is a recognised and widely-published scholar, educator, and academic entrepreneur. He co-founded and led the leading business school in China (CEIBS, Shanghai) and in Russia (MSM SKOLKOVO, Moscow). He currently holds the prestigious Coca Cola Chair in Marketing at the Olayan School of Business, AUB (Beirut, Lebanon)

Dr. Wilfried Vanhonacker is a recognised and widely-published scholar, educator, and academic entrepreneur. He co-founded and led the leading business school in China (CEIBS, Shanghai) and in Russia (MSM SKOLKOVO, Moscow). He currently holds the prestigious Coca Cola Chair in Marketing at the Olayan School of Business, AUB (Beirut, Lebanon)

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)