By Simon Collinson, Melvin Jay & Mary Pizzey

Walmart earns $400 billion each year by serving over 100 million customers every week in 4,500 retail locations (covering a land-area that is greater than Manhattan) with products from over 100,000 suppliers. A big part of its success lies in what it chooses not to do as a company. It has a focused strategy. But another major success factor is the way in which Walmart’s organisation structure aligns people and processes behind its massive product delivery system. It has over two million unique, individual employees working in a streamlined way to add value to its customers.

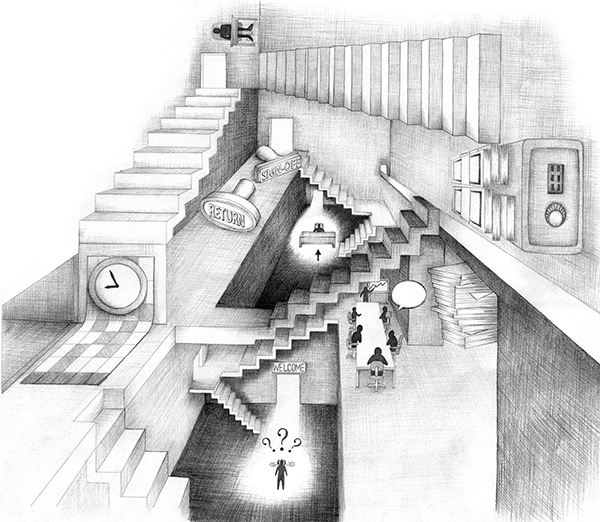

Our recent research shows that most organisations have evolved to be too complex. This prevents people in these companies from focusing on the most important things, performing key activities efficiently or making important decisions fast enough. Costly complexity resulting from organisational design problems is one of the key areas that constrain the performance of firms of all sizes and across all industry sectors.

Organisation design (OD) refers to how a business is organised and structured to deploy people and resources to add value to customers. It includes the structural divisions, such as business units or functions (sales, manufacturing, finance etc.), the relationships between them and the way that decision-making is organised. Firms organised around product groups or global regions, or as matrix or network structures, all suffer from the same challenge: how to avoid the kind of ‘corporate treacle’ which slows down or prevents, rather than facilitates, value-adding activities.

What do we mean by ‘complex’?

Complex is more than just ‘complicated.’ Think about aeroplanes. These are complicated and have become ever-more complicated (larger, faster, with more features, parts, controls etc…), but they are (relatively) predictable.

Change an input or tweak a control lever and they respond as we would anticipate (which is good if you are a frequent flyer). In a similar way some organisations are more stable and predictable than others. They are therefore more complicated than complex. But many are the opposite; they are ‘complex adaptive systems’ where a change in structure, processes, roles and responsibilities or incentives can trigger unpredictable knock-on effects. They are also full of frustrated managers and employees fighting the corporate treacle that prevents or distracts them from adding value for customers.

Some managers even say they succeed in reaching their goals despite the organisation. They are continuously hindered and constrained, rather than helped, by the processes, procedures and bureaucratic systems surrounding them.

We break down organisation design into the following components:

• Governance: who can make what decisions and the documented policies and procedures that guide decision-making.

• Structure: the layers, divisions and sub-units of the organisation, how the work is divided, allocated, coordinated and supervised.

• Capabilities: the specialist knowledge and skills that are needed and the routines and practices that develop and apply them.

• Roles and responsibilities: who does what to get the work done.

• Culture: the way we do things, communication and behaviours.

Achieving simpler and more effective organisation designs should be a central goal for corporate leaders. So how can they recognise when OD has become a source of costly complexity?

Organisational complexity: the symptoms

• Busy but ineffective people: People appear to be permanently busy and stressed, but the company is not progressing in the right direction.

• It is difficult to get even simple things done, e.g. travel authority, small expenditure sign-off.

• Interdepartmental conflict: A lack of alignment and overlap- ping responsibilities means that departments are working on the same things or against each other.

• Lots of KPIs and measures: Everything is measured and reported as managers try to understand and control what is happening at the levels below them.

• Intensive performance management: Arising from persistent interdepartmental conflict and lack of coordination.

• Late or no decisions: Too many people involved in key decisions, too much or irrelevant information and people reluctant to take a risk.

• Poor morale and engagement: People and departments are pulling in different directions, which frustrates people.

• Lots of decision committees: No clear accountability so committees are set up to make decisions.

• Drawn-out sign-off process: Overlaps in roles and decision authority mean lots of people have to agree on one thing.

• Doing the same things in different ways: Departments work independently to achieve the same objectives

We surveyed 600 executives in over 300 European firms to reveal which kinds of organisational complexity created the biggest headaches for them. We were interested in the sources which had the greatest impact on their productivity and their firm’s performance.

High-impact sources include:

• Levels of management and/or the organisational structure.

• Measuring and/or reporting key performance indicators (KPIs) and/or scorecard objectives.

• Making operational expenditure decisions.

• Decision-making processes.

• Making capital expenditure decisions.

• Clarification of roles and responsibilities.

So, two kinds of organisation design problem seem to be increasing the costs of complexity and undermining performance. The first is about the systems and structures for organizing people – how their performance is monitored and measured, how they are hierarchically organized and how their roles and responsibilities are clarified. The second is about the organisation of decision-making in the firm; who decides what, when, where and with whom?

Too many layers of management was a common com- plaint, highlighted as a major driver of additional, costly (non-value-adding) complexity. 26 percent of our sample has more than 10 management levels in their organisation and 19 percent has more than 16! Yet studies have shown that the maximum number of layers from CEO down to the shop floor or customer should be no more than eight, and best practice is closer to six.

OD problems were cited more frequently by poor-performing firms than by high-performers. This was one of the reasons we characterise poor-performers as ‘introverts.’ Overall managers in these firms are overwhelmed by internal sources of complexity which distract or prevent them from focusing on value-adding activities. More successful firms have clearer and more streamlined structures, which allow managers to focus on external strategic threats and opportunities and respond to these to remain competitive.

What can be done to address Organisation Design complexity?

The beauty of Henry Beck’s 1933 legendary map of the London Underground lies in what was left out. Likewise, the key to the right organisation design is getting the right people doing the right things in the right way – nothing more and nothing less.

Getting to the ideal model will require either simplification of your current OD or a complete re-design, depending on your organisation.

Making the current OD simpler

Applies when your strategy has not changed, but you are suffering the symptoms of OD complexity.

Right things

1.Your strategy guides you on the right things: The sole purpose of your organisation design is to organise your people to do the things that will deliver your strategy. A great deal of complexity is driven by mismatch between strategy and what people are doing. Check for:

a.Having a right, clear, well communicated strategy that it is clear to all. Complex strategy = complex OD.

b.Tinkering: a continually changing strategy leads to con- fusion and constant re-structure.

2.Your strategy also tells you what to measure: Measure few things, measure the right things:

a.Link all measures to your strategy so that people are incentivised in the right way.

b.Keep the number of measures minimal – no more than five goals at the corporate level.

c.Make sure that all measures are outcomes-based not activity-based.

d.Make sure there are no contradictions between measures and that no measures have unintended consequences (e.g. short call centre times and customer satisfaction).

Right way

1.Optimise the number of layers: the target should be a maximum of 8 layers between the CEO and front line, with a discreet level of decision authority at each layer.

2.Optimise the spans of control: the optimum span is around 6-12 for professionals (more for operations); too many reports means the manager can’t track whether the right things are getting done and may be tempted to add complexity by increasing reporting requirements. The more skill and specialism is required in the roles, the narrower the spans should be.

3.Cluster: Group similar skills, experience and outputs – for example it may be tempting to put facilities within HR’s remit, but their lack of knowledge in the area is likely to drive more widespread complexity.

4.Interrelationship between spans and layers: if the number of employees stays constant, reducing layers will increase spans – keep checking whether by removing one type of complexity you are creating another.

5.Simplify decision-making: Common causes of poor decision- making include mistrust, unclear accountability, information overload and the fact that people like to add information without taking any away.

a.5 steps to simplifying decision making are:

• Be clear on WHAT you are deciding.

• Consider the accuracy versus time trade-off.

• Optimise WHO is involved: the right number of people, clear decision accountability, and decision authority at the right level.

• Be clear on HOW you will decide: map a clear process, clarify information needs, have clear ‘decision lock’ points, standardise common decision types and use the right decision style for your organisation or the context (autocratic, consultative or collaborative).

• Make the decision and stick to it! Don’t allow the debate to continue and stop implementation.

6.Simplifying the matrix: Most organisations now operate as a matrix, where complexity is driven by divided loyalty, a sense of less control over the outcome, and ambiguity. Matrix complexity can be reduced by minimising the number of matrix connections, restricting matrix working to senior levels (e.g. where an individual has both a geographic and functional reporting line), minimising the number of decisions made in the matrix and making sure roles and measures are aligned and crystal clear. It’s important to keep reinforcing good matrix working behaviours so people understand the ways of working and behaviours that you want them to exhibit in matrix situations – this can be done through training, rewards and timely, open communication. Good matrix working behaviours include clarifying priorities, defining which decisions should be made using the matrix and which should not, and escalating matrix disputes to the appropriate level.

Right people

1.Clarify roles and reduce duplication: For your OD to work, people need to know exactly what their role is, how things are meant to be done, and who they are meant to be done by. Duplication needs to be eliminated.

a.Clarify how each role contributes to the strategy, identifying up to 5 projects or key activities per role, with out- come-based measures for each.

b.Eliminate duplication/overlap between roles, and en- courage people to say if they spot it.

c.Get radical with your RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Involved) – only do this for key activities/ decisions, minimise the number of people in each role, and support with clear communication on ways of working.

2.Clarify and build capability: Be clear on what skills are needed to achieve the strategy, and identify gaps. Use the ‘stars’ who have strong capability to coach the ‘potentials’ who have capability gaps but can be developed. Strugglers who are unlikely to attain the capability to do their roles need to be managed proactively – either moving to a different role or out of the business altogether. The mere presence of people who are not adding value creates complexity, as others have to find ways to work around them or keep responding to redundant requests.

Re-designing for a new, simpler OD

The strategy has changed significantly, or it is clear that the existing OD is fundamentally broken.

Many business leaders would not start with their current organisation design if given a choice. Zero basing leads us to the optimal OD for the organisation. Whilst actually implementing the zero-based OD in its entirety may not be realistic, it does provide a benchmark to work towards. For example, the absence of a very active department from the zero-based design would spark an important debate – is it eroding more value than it is adding due to the complexity it creates? Here is our zero basing approach:

1.Make sure everyone understands and is aligned around your strategy (don’t just assume).

2.Understand how people are currently using their time: e.g. what percentage of management time is being spent on back

office admin rather than value creation?

3.Identify what people should be doing with their time: make the distinction between actually doing and should be doing. Challenge each activity in terms of whether it should be stopped altogether, started (i.e. there is a gap) or continued as-is.

4.Cluster activities into logical groupings (e.g. by skills, location and outcome)

5.Who will need to collaborate and how? Here it is important to make sure the design supports intensive collaboration relationships e.g. between marketing and R&D. One way of doing this is to look at value chains across the organisation – starting with inputs (e.g. a customer enquiry) and going through the steps it takes to turn those inputs into value (e.g. the customer paying for goods and services).

6.Create the new organisation design. Here are some key design principles:

a.Set targets for layers (maximum.8) and spans of control (ideally 6-12).

b.Design the matrix/collaboration model.

c.Keep it lean – eliminate activities that don’t support achieving the strategy.

d.Set clear design rules/guidelines where lower level design is delegated.

Conclusion

Everyone can see the signs of organisation complexity in their business. Leading executives that we have talked to confirm that this is one of the major challenges for firms at a time when managers need to be responding quickly and effectively to external competitive threats and opportunities. If managers are overwhelmed by over-complex and bureaucratic systems inside their organisations they will not be able to focus on the strategic priorities necessary for firm survival.

Simpler structures and simpler strategies reinforce each other for better performance.

All managers can help reach this goal. Start by checking whether your OD is fit for the purpose of achieving your strategy then decide whether a simplification of the current OD or a full redesign is needed. By challenging your OD on the principles outlined in this paper, you can start making real headway towards eliminating the destructive symptoms of complexity.

This article is based on the new management book, From Complexity to Simplicity, co-authored by Simon Collinson, Professor of International Business and Innovation at Henley Business School, and Melvin Jay, founder of the Simplicity Partnership. Find out more about the book at www.fromcomplexitytosimplicity.com

[/ms-protect-content]