The process of selecting people, in business as in social relationships, tends to focus on the “good” characteristics we are looking for. However, as Adrian Furnham points out in this intriguing article, we would be well advised also to look out for those “dark-side” traits that could well give problems further down the line.

We like to think of ourselves as insightful, shrewd and perspicacious judges of others. Through our many life experiences, nearly all of us believe we can accurately assess others’ ability, personality and motivation. Hence, we earnestly think we are rather good at the whole business of selection.

The data would suggest otherwise. Think first about the divorce statistics. Most of us spend some considerable time, effort and money gathering data on a potential mate, yet something like 40-50% of marriages fail. The stats are little better on the appointment of senior managers, of whom similar numbers fail and derail. The data on CEO derailment and failure is astonishing, particularly considering the effort that went into recruiting and selecting them. So what goes wrong?

Three Crucial Issues

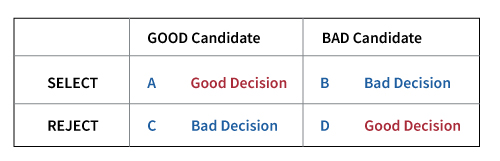

First, selection involves both “select-in” and “select-out” – looking for characteristics you want and, more importantly, don’t want. It is the failure to do good select-out work which means that potential derailers get overlooked (see diagram). Select-out criteria are often thought of as “not enough” of the select-in criteria, rather than something different. If people are asked to list a number of characteristics they do not want in an individual, they usually have no difficulty in answering, but these are not always covered in the competencies. This topic will be addressed in detail.

Second, when selecting for particular competencies or traits (teamwork, innovativeness), many assume more is better (linearity), rather than a more cautious curvilinear approach (optimal amount). The psychological concept of abnormality implies extremes of normality. Thus, while high self-esteem is good and healthy, this might tip over into subclinical narcissism and then clinical narcissism. Being rated as a very strong team player may indicate someone who “hides” in teams and is dependent, rather than independent. A “strong analytic thinker” may easily suffer from “analysis paralysis”. Someone who is rated as a mover and a shaker may be dysfunctionally impulsive and a bully. A leader praised for their emotional intelligence and empathy may be unable to make tough, but necessary, people decisions.

Third, when an analysis of failed and derailed leaders is made, there is a consistent and, for many, surprising finding: that there were many early biographical markers of their future failure. That is, when looking back, there were clear indicators of the traits that later proved so crucial in leading to derailment. This suggests that selection may well be advantaged by the use of biographical or biodata instruments. In short, the past is a very good predictor of the future.

The Dark Side

Over the past 15 to 20 years, there has been great interest in the relationship between what have been called the dark-side traits and work failure, rather than the bright-side traits and work success.

Psychologists are interested in personality traits, psychiatrists in personality disorders. Both argue that the personality factors relate to how people think, feel and act. It is where a person’s behaviour “deviates markedly” from the expectations of the individual’s culture that the disorder is manifested.

One of the most important ways to differentiate (normal) personal traits/style from personality disorder is flexibility. There are lots of difficult people at work, but relatively few whose rigid, maladaptive behaviours mean they continually have disruptive, troubled lives. It is their inflexible, repetitive, poor stress-coping responses that are marks of disorder.

But it is not an “all-or-nothing” situation; everything is on a continuum from normal to abnormal. There are degrees of abnormal, such as, for example, low self-esteem (SE), average SE, high SE, subclinical narcissism, clinical narcissism.

Personality disorders influence the sense of self – the way people think and feel about themselves and how other people see them. The disorders often powerfully influence interpersonal relations at work. The antisocial, obsessive-compulsive, passive-aggressive and dependent types are particularly problematic in the workplace. People with personality disorders have difficulty expressing and understanding emotions. It is the intensity with which they express them and their variability that makes them odd. More importantly, they often have serious problems with self-control.

At the simplest level, there are three “give-away” markers of potential derailing disorders. First, the ability to form and maintain happy healthy relationships at, and outside, work. Is there evidence that an individual is liked, trusted and supported by a friendship network that is stable over time?

Second, are they sufficiently self-aware about themselves, their abilities, how others experience them, how healthy their life-style is, and how “normal” their reactions are? A great deal about coaching and therapy is about helping people understand themselves. Many failed CEOs were clearly deluded about their abilities, which may have served them well for some time (pathological high self-esteem), but derailed them in the end.

Third, can they deal with change? We learn nothing from success, except to keep repeating the behaviour, but we can learn a lot from failure. Learning new skills, new behaviour routines is not easy, particularly as one gets older. The fragile are not agile. And yet, being flexible, adaptable and able to negotiate around new and complex issues is at the heart of being successful.

Assessing the Dark-Side, Select-Out Variables

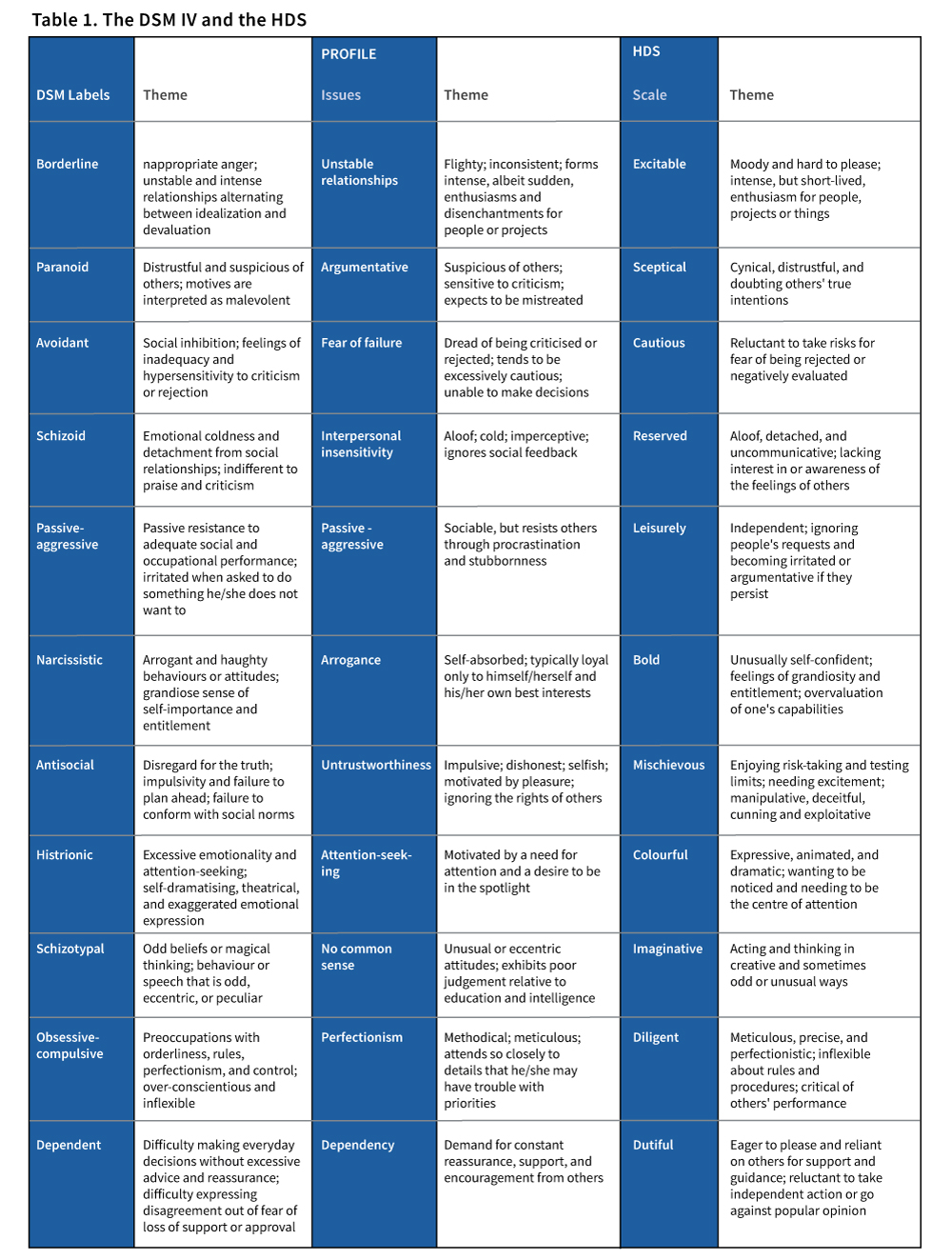

The greatest progress in this area occurred when Robert Hogan developed the Hogan Development Survey (HDS). The idea was to use the categories of the personality disorders, but to conceive of “dark-side” tendencies, rather than disorders. The test is now widely used to assess dysfunctional interpersonal themes. These dysfunctional dispositions reflect one’s distorted beliefs about others that emerge when people encounter stress or stop considering how their actions affect others. Over time, these dispositions may become associated with a person’s reputation and can impede job performance and career success.

It is these dark-side factors that are the select-out variables. This table shows the psychiatric labels, but also the more interpretable HDS labels.

The measure gives very helpful advice if your scores are high. For instance:

- Leisurely: You are independent, socially skilled, and able to say “no” diplomatically. You make few demands of others and expect to be left alone to do your work in your own way. You see more incompetence in the world than others do. Although you may think others are naïve, you could profit from their optimism and trust. Understand that you may become irritable when others try to coach you. Allow yourself to be more easily influenced by friends or family, and more willing to do the little extra things they ask you to do. Limit the promises you make to others, but be sure to fulfil the promises and commitments you do make.

- Mischievous: Other people may think that you follow your own agenda and don’t consider how your decisions impact them. As a result, they may be as reluctant to make commitments to you as you seem to be in return. Thus, you need to be careful to follow through on all your good-faith commitments. If you find circumstances have altered the conditions under which you made a commitment, then negotiate the changes with the people to whom you have made the promise – rather than simply going on about your business. You tend to have a higher tolerance for risk than most people. Be aware that not everyone is as adventurous as you seem to be. You may have disappointed others by not following through. You need to acknowledge your errors and make amends – rather than trying to explain the situation away. At your best, you are charming, spontaneous and fun. You adapt quickly to changing circumstances, you handle ambiguity well, you add positive energy to social interactions, and people like being with you.

- Diligent: You have high standards for performance, are planful and organised. In addition, you provide structure and order for your staff. Tackle issues with outside-the-box thinking. Try not to solve every problem in the same way. Practise delegating to your staff. This provides them with valuable developmental experiences and opportunities to learn. Your high standards result in high-quality work. However, be careful not to criticise others continually who do not share your values for impeccable work.

The research in this area has revealed various consistent findings. The most interesting is that paradoxically some of the dark-side traits are implicated in (temporary and specific) management success. Thus the “naughtiness” of the antisocial mischievous type, the boldness and self-confidence of the arrogant narcissist, the colourful emotionality of the histrionic, and the quirky imaginativeness of the schizotypal type may in fact help them climb up the organisation.

Another issue refers to the curvilinearity or optimality of these traits. That is, at high levels, these traits are nearly always “dangerous” and associated with derailment and failure, but at moderate levels they may even be beneficial.

Also, there are some of these dark-side traits which are nearly always associated with lack of success at work. Thus cautious/avoidant and reserved/schizoid people rarely do very well at work, except in highly technical jobs where they work on their own. Their low social skills and inability to charm and persuade others mean that they very rarely occupy positions of power and influence.

There are all sorts of recommendations to prevent one’s dark side from being destructive.

For instance, take a 360-degree (multi-source) assessment to increase your awareness of potential problems; solicit feedback from honest and insightful friends on a regular basis; take responsibility for, and invest in, your own development; learn what abilities, insights and skills are needed for senior positions; try to understand the motives and abilities, strengths and weaknesses of those you work with; be clear about the demands and responsibilities of your job; hire people with complementary skills to your own; delegate to, develop and empower your team; deal with employee problems as soon as they arise.

Further, it should never be forgotten that most people work in teams and are neither dependent nor independent at work, but interdependent. Thus, work outcomes are a function of group interaction and dynamics, which is a part-function of the personality of all the members.

And, in selection, never forget to search actively for the characteristics that you don’t want.

About the Author

Adrian Furnham is Principal Behavioural Psychologist at Stamford Associates in London. He is also Professor of Psychology at BI, The Norwegian Business School. He is the author of over 90 books and 1,200 peer-reviewed scientific papers.

Adrian Furnham is Principal Behavioural Psychologist at Stamford Associates in London. He is also Professor of Psychology at BI, The Norwegian Business School. He is the author of over 90 books and 1,200 peer-reviewed scientific papers.

References

-

- Babiak, P., & Hare, R. (2006). Snakes in Suits. New York, NY: Regan Books.

- Dotlich, D. & Cairo, P. (2003). Why CEOs fail. New York: Jossey Bass.

- Furnham, A. (2014). Bullies and Bastards. London: Bloomsbury.

- Furnham, A. (2018) Personality and Occupational Success. In Virgil Zeigler-Hill & Todd K. Shackelford (Eds). The SAGE Handbook of Personality and Individual Differences. New York: Sage.

- Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2001). Assessing Leadership: A View from the Dark Side. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9, 40-51.