By Paul F. Nunes and Joshua B. Bellin

Companies are increasingly finding their marketing messages contradicted – or worse, turned against them – by a new set of “advisers.” These online channels, including TripAdvisor, Amazon.com and many more, operate beyond marketers’ control and have great reach and significant power to influence consumer opinion. Can this territory be regained? Yes, but only if marketing leaders learn to understand the battlefield of influence. They can then draw from a set of four tactical responses to ensure that their key messages remain accessible, relevant and influential.

In the last ten years, many marketing organizations became aware that their customers had “escaped.” They had fled the controlled sales channels of the pre-Internet age when stores were solid and physical distances mattered. Instead they were acting in unpredictable ways, turning to components of multiple channels before buying (or turning elsewhere).1

Today the problem has just gotten bigger. Customers are not just exploiting alternative sales channels to inform themselves about products and company reputations before making a purchase. They’re also turning to a wide variety of online sources for advice, in domains where traditional marketing messages often have very little influence or impact.

Winning the battle is not easy. Investing more in yesterday’s styles of advertising is not the solution, and simply attempting to manipulate social media and search engines won’t work and may blow up when it’s discovered.

To do better, companies must understand the nature of the new battlefield, in three particular ways:

They need to understand the combatants. Lacking an appreciation for how alternative sources actually influence customers – and just how savvy customers can be at assessing the sources’ quality – some companies have been led seriously astray in their responses. Just ask the communications managers at several well-known consumer goods manufacturers who have been exposed over the last few years for flooding review sites with glowing praise for their products.2

Understanding these new combatants is now more important than ever. Influential customer reviews, social network “friends,” more easily searchable expert opinions and even automated recommendation and price-comparison engines all increasingly intervene between a company and its customers. As a result, customers’ mindsets have actually changed. An annual survey of societal trust found that, for the first time in 2006, customers considered “a person like yourself” to be the most trusted source for advice, as opposed to other sources such as business or government.3

They need to understand the different battle fronts. Some companies have chosen the wrong times or wrong forums in which to try to exert influence. Certain online retailers made this mistake by affiliating with a social networking feature that automatically shared users’ purchases with their network, without explicit consent from the user. Understandably, a privacy backlash was the result.4

More than ever before, companies must understand and appreciate the various fronts on the battlefield of influence. They are not fighting to have their messages heard only when customers weigh their purchase options. Thanks to the internet and mobile technologies, customers often access alternative information sources before the point of purchase – as 16 percent of shoppers do on their phones in retail locations – and then can effectively influence other consumers after their purchases too. A recent Accenture survey found that 30 percent of customers have penned a negative review after a disappointing purchase or experience.

They need to anticipate asymmetric combat. The weapons on the battlefield are complex and constantly evolving. A popular fast food chain realized how little they knew when it introduced a new hashtag on Twitter – hoping that customers would share fond memories of the restaurant. Instead, a torrent of negative and unflattering responses was unleashed for all Twitter users to see.5 With some understatement, the company’s social media director admitted that “within an hour we saw that it wasn’t going as planned.”6

In reality, the new battlefield features asymmetric combat. Fighting alternative sources of influence is nothing like countering competitors’ marketing. Viral opinions, for example, are impossible to contain: they are often global and instantaneous and oftentimes, anonymous in origin. And companies who call in lumbering tanks to fight these nimble guerilla tactics find themselves outflanked.

It’s therefore more important than ever for marketing departments to understand the altered influence battlefield, and the different ways by which the internet and new media have changed how their customers find and absorb information about their company’s reputation and products.

Figure 1 illustrates the new and enhanced sources of buyer influence that can sway consumers. Companies must be aware about both where customers are becoming informed today, as well as where new sources could influence them down the road.

To decide where, when, and how to respond, companies should consider two sets of questions:

The first set focuses on the sources themselves. To what extent does each source of influence motivate our customers to make a purchase, and when? (Not surprisingly, the answer is different depending on whether the item is a vacation package or a candy bar. See “The complex world of consumer reviews.”) Are typical customers looking for trusted advice, credible expertise, or broad consensus about quality and experience? Are they responsive to targeted promotions? Are they loyal to the brand?

The second set looks inward, at organizational capabilities. What level of aptitude does our company have when it comes to influencing through different sources? Where do we have the skills and capabilities we would need to convey our messages effectively? For example, if we’re talking about word of mouth marketing (tailored recommendations and social media) do we really know how to target and reach influencers?

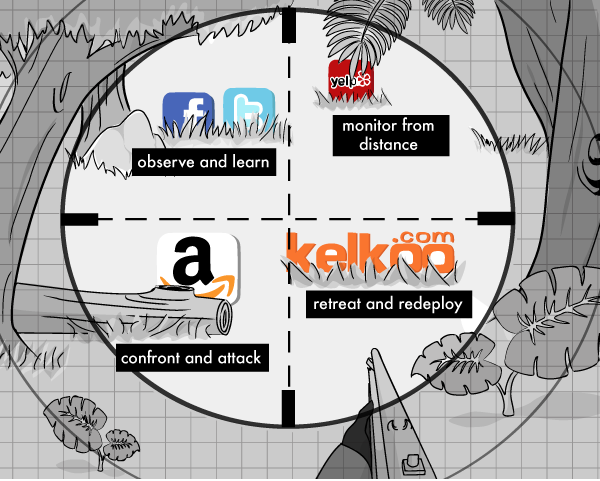

For each source of buyer influence on Figure 1, marketing departments can decide on a tactical approach based on these two questions – whether to confront and attack, retreat and redeploy, observe and learn or monitor from a distance. (See Figure 2.) These four moves form the core of a marketer’s tactical playbook in the new battlefield of influence.

Confront and attack: When companies know that a certain type of influence is effective, and when they believe they can successfully reach customers in that way, they should press ahead when they see an opening to do so.

Disney, for example, in advertising its 2009 animated blockbuster Up, touted the Pixar film’s 98 percent “Fresh” score on RottenTomatoes.com – an online opinion aggregator – in addition to the more traditional blurbs from expert film reviewers. The LA Times called this “an unusual endorsement.” But according to the company’s marketing chief, “People want to know what the consensus is. I am a huge believer that in today’s culture, people don’t pay as much attention to individual voices as to the aggregate score.”7 Up performed stronger than analysts had been expecting, ranking number one on its opening weekend and going on to be one of Pixar’s highest grossing films.

Similarly, Malta-based Corinthia Hotels, with properties in Europe and Africa, responds directly to customer feedback over social media. According to the company’s social media strategist, “It can seem quite risky for a hotel group to put customer service on social media platforms and public websites, but we’re willing to take that risk. The reality of the social web is that whether we engage or not, the conversations about our brand are happening anyway.” The company finds that engaging over social media highlights the hotel chain’s transparency and builds trust with consumers – a major factor when it comes to hotel bookings.8

Retreat and redeploy: Just because a company can reach customers through a particular source of influence doesn’t necessarily make it a wise investment – especially if the source of influence has little impact. Companies must be able to track whether reaching customers on a particular source is wasted effort when it comes to actually influencing them. And if it is, then a hasty retreat to refocus on other areas shouldn’t be lamented.

General Motors, for example, recently pulled all their paid advertising from Facebook. Yet, as GM’s director of social media tweeted, “We have more than 8mil friends on FB; not leaving them; engagement & content isn’t same as advertising.”9 GM’s ability to distinguish between two different sources of information – paid advertising and social outreach – and the decision to continue one and not the other, is an example of a successful “retreat and redeploy” move.

Observe and learn: Where customers are highly influenced by a certain source, but a company’s ability to bring their messages to consumers is limited, they’re better off observing and learning in order to build their capabilities – so that they can better respond by using that effective source of influence. Why does this type of advice influence customers? What makes it credible? What room is there to engage actively? Observing and learning is especially important for new and untested sources of influence.

Take yogurt brand Chobani’s slow but steady engagement on the social media site Pinterest. That site enables users to grab and save images from across the Web and, according to AdWeek, has 11.7 million unique visitors in the US (most of them women). The digital communications manager for Chobani explained that the company joined the site after spotting its fans sharing recipes and pictures. The company recently began reaching out to and sharing content with some 2,000 followers over the site – a modest entry – but one which will enable the company to learn the ins-and-outs of the social media platform.10 Chobani’s experimentation with new ways of reaching customers has contributed to its rapid rise in popularity from a new brand in 2007 to the third best-selling yogurt brand in the US today.

Monitor from a distance: Not all sources will prove influential to customers, and, in any case, companies will sometimes be limited in their capabilities to respond. But that doesn’t mean they should be entirely absent. Monitoring the advice that does reach consumers from various sources of influences can yield powerful businesses insights to hook customers in other ways.

Kraft Foods in particular adapts its products to reflect trends in food-related social media discussions. An executive at the Oscar Mayer division notes that social media research “allows us to explore the fuzzy front end of basic user wants or needs, like what are the flavor trends, what are the usage trends.” Although similar to the kind of ethnographic research that some marketers employ, listening to and monitoring these alternate sources of information provides the company with “a vast data set, bigger than any data set I ever had, and it’s being refreshed constantly.”12

In the end, companies must remain eternally vigilant. Influence battles won’t be won decisively. Alternative sources of buyer influence are constantly-moving targets, and the pace of new innovations means that consumers can be influenced differently month to month, or even week to week.

Companies must therefore not only continuously re-learn how influence gets peddled in the marketplace today – they must constantly reevaluate how customers are influenced, and what the appropriate response should be. And though field marshal Helmuth von Moltke was right to say “no plan survives contact with the enemy,” no good general goes into battle without one.

About the authors

Paul F. Nunes, based in Boston, is the executive director of research at the Accenture Institute for High Performance.

Joshua B. Bellin is a research fellow with the Accenture Institute for High Performance, also based in Boston.

References

1. (See “The Customer Has Escaped” by Paul F. Nunes and Frank V. Cespedes, Harvard Business Review, November 2003.)

2. WSJ, “A Fake Amazon Reviewer Confesses, 7/9/09; NYT, “Carbonite Stacks the Deck on Amazon,” 1/27/09

3. Edelstein Trust Barometer

4. NYT, “Facebook Retreats on Online Tracking, 11/30/07

5. Gizmodo, “McDonald’s Twitter Marketing Turns into Disgusting Customer Revolt,” 1/24/2012

6. http://paidcontent.org/2012/01/24/419-mcdonalds-social-media-director-explains-twitter-fiasco/

7. LA Times, “Mixed reviews for Rotten Tomatoes and other aggregate websites,” 6/13/09

8. http://www.tnooz.com/2012/05/21/how-to/social-media-listening-in-travel-is-not-enough-so-here-are-three-ways-to-respond/

9. Bloomberg BusinessWeek, “Why GM and Others Fail With Facebook Ads,” 05/22/12

10. AdWeek, “Brands Pinning it on Pinterest,” 02/19/12

11. http://www.emarketer.com/blog/index.php/case-study-sephora-offers-ratings-reviews-mobile/

12. http://www.informationweek.com/thebrainyard/news/231000822/how-kraft-foods-listens-to-social-media

13. Sussan, Gould and Weisfeld-Spolter, 2006

14. Lee, 2009

15. Doh and Hwang, 2009

16. Clemens and Gao

17. Mudmabi, 2010

18. CompetePulse, “Mixed Results for Facebook Among OTAs,” 02/14/12

[/ms-protect-content]