By David Bartlett, Economic Advisor, RSM International

Solidation prevails in the United Kingdom and other member states.

• The divergent growth paths of developed and emerging markets, which foretell major structural shifts in the global economy.

Shape of the Global Recovery

In summer 2010, the ebbing of GDP growth in the U.S. and the succession of sovereign debt crises in the European Union raised concerns over the sustainability of the economic recovery. However, by year’s end fears of a “double dip” recession had largely subsided. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts world GDP growth of 4.2 percent in 2011, down from 2010’s 4.8 percent yet sufficiently robust to validate hopes for a rebound from the deepest economic contraction since the 1930s.

But the IMF projections indicate a highly uneven recovery, with large variations in GDP growth both between and within key regions of the global economy. These varying growth trajectories illustrate the following:

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]• Differences in national and regional exposures to the financial crash of 2008-2009, which inflicted deep damage on some developed economies (e.g., Ireland, Spain) but had less serious effects on Germany and other countries that eluded asset bubbles

• Variations in economic policy responses to the downturn, manifested by the tension between the United States (which has prioritised economic stimulus) and the European Union (where fiscal consolidation prevails in the United Kingdom and other member states)

• The divergent growth paths of developed and emerging markets, which foretell major structural shifts in the global economy.

Regional Growth Trends

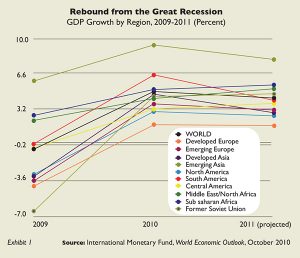

Exhibit 1 below reports growth trends by region. Emerging Asia leads the global recovery with a projected growth rate of 7.9 percent in 2011. Within that group, China and India are forecast to grow by 9.6 and 8.4 respectively. Rising domestic demand, expanding foreign trade, and continuing infrastructural investments augur favorably for high and sustained GDP growth in the those giant emerging markets. Other countries in the Emerging Asia group will enjoy strong if unspectacular growth rates in 2011 (Vietnam 6.8 percent, Indonesia 6.2 percent, Malaysia 5.3 percent, Philippines 4.5 percent, Thailand 4.0 percent). These growth projections surpass rates in Developed Asia (Japan 1.5 percent, New Zealand 3.2 percent, Australia 3.5 percent).

The Middle East (5.1 percent) and Former Soviet Union (4.6 percent) are also poised for solid growth in 2011, driven by the recovery of international energy prices following the contraction of 2008-09. Russia, which suffered a 7.9 percent GDP decline in 2009 as oil and gas prices plummeted, is projected to grow by 4.3 percent in the coming year. The energy-driven economies of the Persian Gulf (Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates) face comparable growth prospects in the coming year. Small, resource-poor ex-Soviet states like Armenia, Georgia and Moldova are forecast to grow moderately (3.5-4.5 percent) following a devastating downturn that virtually erased a decade of economic growth.

Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to grow by 5.5 percent in 2011, led by resource-driven DRC Congo (8.7 percent) Nigeria (7.4 percent), and Angola (7.1 percent). South Africa, the Sub-Saharan’s largest and most developed economy, will register a more modest growth rate of 3.5 percent.

Consistent with the historical pattern, South America is projected to underperform relative to Emerging Asia (4.1 percent regional growth in 2011). Chile (which more closely resembles the East Asian export-led economies than other South American countries) is poised for a 6.0 percent expansion in 2011. Colombia (4.6 percent), Brazil (4.1 percent), and Argentina (4.0 percent) are expected to reach growth rates comparable to those preceding the downturn. Despite the rebound in global energy demand, Venezuela is forecast to grow by just 0.5 percent in 2011, demonstrating waning investor confidence in the Chavez regime’s management of that oil-centric economy.

Emerging Europe lags behind other emerging markets, reflecting that region’s high exposure to the global financial crash and strong dependence on the slow-growing export markets of Western Europe. Slovakia, whose fortuitous adoption of the Euro in January 2009 insulated the country from the currency speculation that beset non-Euro countries in Central and Eastern Europe, is forecast to grow by 4.3 percent in 2011. Poland follows at 3.7 percent. The Baltic Republics, which suffered double digit economic contractions in 2008-09, are projected to grow by 3.1–3.5 percent. Hungary (whose recent policies have alarmed the international financial community) and Romania (where poor governance frustrates development of a well-endowed economy) are set for growth in the 1.5–2.0 range. Turkey stands as the growth champion of Emerging Europe, with a projected GDP growth of 7.3 percent in 2011.

Developed Europe anticipates 1.6 percent growth in 2011, with sluggish growth likely to continue through mid-decade. Germany, whose export sector spearheaded the highest growth rate (3.3 percent) in the G-7 in 2010, is projected to slow to 2.0 percent in the coming year.

This growth path reflects (1) persistent structural rigidities in the West European economies that long preceded the downturn, (2) macroeconomic constraints facing Euro zone members, two of which (Greece and Ireland) have undertaken severe austerity programmes, and (3) policy decisions by non-Euro countries (notably the United Kingdom) to accelerate fiscal consolidation at the expense of economic growth.

There is a different dynamic in North America. Canada, whose financial and housing sectors avoided the turmoil of other developed countries, is forecast to grow by 2.7 percent in 2011. The United States is projected to grow by 2.3 percent in 2011, lower than 2010’s growth rate (2.6 percent) but outpacing most West European countries.

The American economy may grow at a higher rate if the stimulative effects of the recently negotiated U.S. tax accord materialise. That agreement (which includes a two-year extension of the Bush Administration’s income tax cuts and a 2 percent reduction in the Social Security tax) demonstrates the willingness of American officials to forgo deficit reduction to stimulate growth in an economy whose unemployment rate (near 10 percent) was a pivotal issue in the 2010 midterm elections.

Sovereign Debt

The tension between economic growth and fiscal consolidation is a central feature of the post-global crisis landscape. These contradictory imperatives are particularly salient in developed economies that face a combination of weak GDP growth and mounting fiscal imbalances.

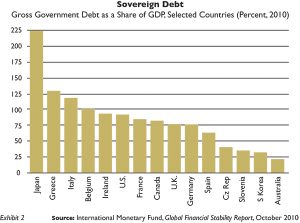

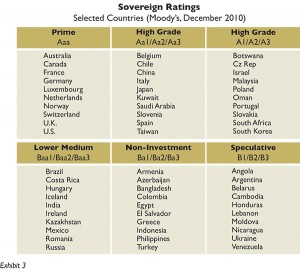

Exhibit 2 and Exhibit 3 report the sovereign debt shares and sovereign debt ratings of selected countries.

Japan is an outlier in the sovereign debt sphere. Despite its standing as the world’s foremost creditor nation, Japan carries a mammoth governmental debt (225 percent of GDP) resulting from two decades of stagnant growth and heavy deficit spending. On the opposite end of the spectrum lies Australia, whose small sovereign debt (22 percent of GDP) illustrates prudent macroeconomic policies and robust tax revenues generated during the country’s natural resource boom in the early and mid-2000s.

Between the polar cases of Japan and Australia, the sovereign debt list reveals a wide range of outcomes. France, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom maintain prime credit ratings despite comparatively high debt ratios. The U.K.’s austerity programme reflects the Cameron governments’s determination to curtail deficit spending and preserve the confidence of international bond dealers. The bond market has already penalized Greece, whose debt is rated sub-investment grade. On December 17, Moody’s announced a five-notch downgrade of Ireland. While recent discussions of Europe’s financial woes has focused on the Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain credit rating agencies voice growing concerns over the financial stability of other EU countries. On December 14, Standard & Poor’s signaled possible downgrades of Austria and Belgium, small EU economies with large debt-to-GDP ratios.

At $13.9 trillion, the U.S. national debt nearly equals the GDP of the world’s largest economy. The debt/GDP ratio of the United States will likely pass 100 percent in coming years as the fiscal stimulus package (which like the one enacted by the Obama Administration in early 2009 is completely deficit financed) expands the national debt.

The initial reactions of the international financial community are not auspicious: Obama’s announcement of a tax reduction deal in December 2010 prompted a sell-off of U.S. Treasury bonds, while Moody’s (which has rated U.S. debt “Aaa” since 1917) warned of a potential sovereign downgrade. As the world’s biggest economy that still holds the main international reserve asset, the U.S. enjoys certain privileges unattainable by other countries. However, the bond market’s response to Washington’s recent actions demonstrate that the U.S. cannot with impunity sacrifice long-term fiscal stability in pursuit of short-term economic growth.

Conclusion: Rise of Emerging Markets

It is noteworthy that present anxieties over sovereign debt focus on the problems of developed economies like Ireland, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States. Emerging markets (which experienced a series of financial crises in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s) have displayed notable financial stability amid the recent global downturn:

• A number of emerging economies (Chile, China, Czech Republic, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Saudi Arabia) enjoy “high grade” or “upper medium” ratings of their sovereign debt.

• The simultaneous downgrading of the sovereign debts of other emerging economies (e.g., Hungary) demonstrates an increasing level of discrimination by international financial institutions that treated emerging markets as an undifferentiated asset class in previous crises (Mexico 1984, East Asia 1997-98, Russia 1998, Argentina 1999-2002).

• China now holds the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves (nearly $2.2 trillion) and accounts for the largest share (24.2 percent) of global capital exports. Seven other emerging economies (Russia, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, India, South Korea, Brazil, Hong Kong) rank among the top ten holders of foreign exchange, much of which finances the sovereign debts of the U.S. and other developed countries.

These developments underscore the growing economic power of emerging markets. Augmenting their successes in manufacturing (China), information technology (India), oil and gas (Russia), and renewable energy (Brazil), the BRICs and other emerging markets have become key players in global finance. At the same time, their strong GDP growth paths position the emerging markets as drivers of world economic recovery, a role previously played by the U.S. and EU. While the ‘Great Recession’ has shaken the foundations of many developed economies, the global downturn has strengthened the global economic standing of emerging markets.

About RSM International

RSM International is a worldwide member organisation of independent accounting and consulting firms. RSM International is represented in over 80 countries and brings together the talents of over 32,000 individuals worldwide. The organisation’s total fee income of US$3.8bn places it amongst the top six international accounting organisations worldwide. Member firms are driven by a common vision of providing high quality professional services, both in their domestic markets and in serving the international professional service needs of their client base.

www.rsmi.com

About the Author

David Bartlett, Economic Consultant, has over ten years’ experience of consulting, researching and teaching on international corporate strategy. He specialises in international growth, global manufacturing, foreign sourcing and distribution and corporate risk management.

David is Adjunct Professor of Strategic Management and Organization at the Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota. He has also held faculty appointments at Vanderbilt University (USA), Yerevan State University (Armenia), and the University of World Economy and Diplomacy (Uzbekistan).

David has received a Fulbright Senior Scholarship, Salzsburg Seminar Fellowship and other scholarly awards. He holds a PhD and BA from the University of California and an MA from the University of Chicago.

E: david.bartlett@rsmi.com

[/ms-protect-content]