By William S. Harvey, Vincent Mitchell, Alessandra Almeida Jones and Eric Knight

Over the past several decades, thought leadership has moved from being individual gurus to organisations operating a considerable budget. We define thought leadership as: “Knowledge from a trusted, eminent and authoritative source that is actionable and provides valuable solutions for stakeholders.”

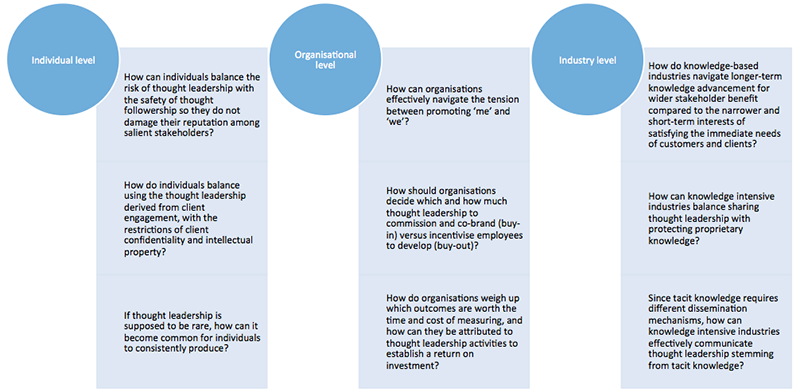

Today, many organisations have a head of thought leadership and thought leadership industry awards. Here we identify nine such difficulties which such organisations face, and organise them according to where tensions can lie at the individual, organisational and industry level (see inset).

Individual thought leadership tensions

Although thought leadership should intrigue, challenge and inspire through generating new ideas and pushing the boundaries of knowledge, we find that thought leadership is often incremental and has led to a cycle of thought followership, copying competitors and developing content that has been tried and tested. This raises the first tension of:

How can individuals balance the risk of thought leadership with the safety of thought followership so they do not damage their reputation among salient stakeholders?

One effective way to begin generating ideas for thought leadership is to identify all the questions that stakeholders are asking, for example H & R Block selfless approach to answering tax-related questions. The solutions created for these challenges become a resource for developing thought leadership content. Moreover, sometimes clients themselves are often a valuable source of new knowledge and new ideas can be co-created with them. However, this client information poses problems for thought leadership as it cannot be divulged for confidentially reasons. This raises the tension of:

How do individuals balance using the thought leadership derived from client engagement, with the restrictions of client confidentiality and intellectual property?

A key issue is that thought leadership is supposed to be rare, original and substantively challenge the status quo in the way we think. But if this is so, clearly not everyone can be a thought leader because if everyone is challenging the status quo, there is no status quo to challenge. Instead, many people resort to publishing poor quality thought leadership which just acts as ‘communication confetti’, which gives the appearance of activity but is light on substance and incoherent.

This raises the tension of;

If thought leadership is supposed to be rare, how can it become common for individuals to consistently produce?

Organisational thought leadership tensions

A challenge of many individuals in an organisation attempting to produce their own thought leadership is that it is difficult to manage the overall organisational brand. This raises issues of who is the owner of the thought leadership or who is the reputation beneficiary and how therefore thought leadership relates to its wider approach to reputation management.

This leads us to ask:

How can organisations effectively navigate the tension between promoting ‘me’ and ‘we’?

In the race to get the best thought leadership, organisations have begun to buy-in from an external provider which is then branded in-house to help position themselves as thought leaders. This is often done when organisations either do not believe their employees can produce high quality thought leadership or they do not think that the opportunity cost of doing so is worth it. The can substitute or complement a buy-out approach where an employee’s time to is bought-out to self-produce thought leadership, for example McKinsey & Company. The cost-benefit for each is uncertain and leads to another organisational tension:

How should organisations decide which and how much thought leadership to commission and co-brand (buy-in) versus incentivising employees to develop (buy-out)?

There is major confusion around how thought leadership can be measured and therefore what the impact of thought leadership is for organisations. Some of the most popular metrics include the number of content downloads, media hits, social media engagement, search engine ranking, client meetings, qualitative feedback, web traffic, inbound web links and quality and quantity of leads, client retention and sales revenue. However, the cost of measuring and analysing these data, and determining how much a specific thought leadership activity caused a certain outcome is difficult and leads to a third organisational tension:

How do organisations weigh up which outcomes are worth the time and cost of measuring, and how can they be attributed to thought leadership activities to establish a return on investment?

Industry thought leadership tensions

Knowledge industries face a broader set of tensions relating to thought leadership. At this level, there is often a tradeoff between the wider social benefit of sharing thought leadership, which may be beneficial to industry, profession or society at large, versus the immediate commercial benefit this creates for the organisation. This is typical of the tension between agency capitalism and stakeholder capitalism, and leads to a first industry tension:

How do knowledge-based industries navigate longer-term knowledge advancement for wider stakeholder benefit compared to the narrower and short-term interests of satisfying the immediate needs of customers and clients?

By definition, thought leadership implies knowledge industries should share their expertise and knowledge, which once in the public domain can be shared further and rapidly. However, sharing the insights of an organisation’s knowledge base indiscriminately can reduce its competitive advantage as others can quickly acquire and use their intellectual property. Knowledge industries then face a delicate trade-off between signalling and giving away their knowledge, between sharing and protecting information, which leads to our second industry tension:

How can knowledge-intensive industries balance sharing thought leadership with protecting proprietary knowledge?

At the heart of knowledge, industries are how they can capture and convey tacit know-how of their knowledge. Yet, one of the distinctive attributes of knowledge professionals is the value they bring through their unique experience and intuition, which is not conducive to codification. This raises a fundamental question of how current thought leadership mediums such as newsletters, blogs, webinars, e-mails, videos and social media postings can capture and convey tacit knowledge and it leads to our third industry tension:

Since tacit knowledge requires different dissemination mechanisms, how can knowledge intensive industries effectively communicate thought leadership stemming from tacit knowledge?

Summary

If managed well, thought leadership can be a significant source of reputation and competitive advantage for individuals, teams, organisations and industries. However, organisations need to recognise, consider and navigate tensions, and the difficulties in attempting to scale up thought leadership activity.

Currently, the volumous thought leadership being created suggests that much thought leadership does not pass the quality threshold test because of some of the tensions we have raised above in creating, developing, sharing and promoting thought leadership. We hope that knowledge practitioners and knowledge management academics will join in research and practice to help better understand how to navigate these and other tensions to help organisations to create a compelling and sustainable thought leadership strategy.

Nine Thought leadership tensions

This article is based on the following peer-reviewed article, which is freely available: Harvey, W.S., Mitchell, V-W., Almeida Jones, A. and Knight, E. (2020). The tensions of defining and developing thought leadership within knowledge-intensive firms. Journal of Knowledge Management.

About the Authors

William S. Harvey is Professor of Management and Associate Dean at the University of Exeter Business School. He is an International Research Fellow at the Oxford University Centre for Corporate Reputation and Chair of the Board of Libraries Unlimited. William advises leaders on reputation, talent management and leadership. @willsharvey

William S. Harvey is Professor of Management and Associate Dean at the University of Exeter Business School. He is an International Research Fellow at the Oxford University Centre for Corporate Reputation and Chair of the Board of Libraries Unlimited. William advises leaders on reputation, talent management and leadership. @willsharvey

Vincent Mitchell is Professor of Marketing at The University of Sydney Business School. After publishing over 200 academic and practitioner papers in journals such as Harvard Business Review, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Economic Psychology, his work has created much impact and resulted in an h index of 59. @ProfVMitchell

Vincent Mitchell is Professor of Marketing at The University of Sydney Business School. After publishing over 200 academic and practitioner papers in journals such as Harvard Business Review, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Economic Psychology, his work has created much impact and resulted in an h index of 59. @ProfVMitchell

Alessandra Almeida Jones, is a marketing and communications professional with a track record in building brands for professional services firms. Particularly skilled in creating thought leadership campaigns, she has pioneered many award-winning marketing initiatives. Alessandra is a regular speaker at marketing forums and has an MBA from Cass Business School. Currently Director of Marketing at Baker McKenzie in London, she has held senior positions at Linklaters, KWM and ABN AMRO.

Alessandra Almeida Jones, is a marketing and communications professional with a track record in building brands for professional services firms. Particularly skilled in creating thought leadership campaigns, she has pioneered many award-winning marketing initiatives. Alessandra is a regular speaker at marketing forums and has an MBA from Cass Business School. Currently Director of Marketing at Baker McKenzie in London, she has held senior positions at Linklaters, KWM and ABN AMRO.

Professor Eric Knight is an organisational theory and strategic management scholar. He has published in FT50 journals as Strategic Management Journal and the Academy of Management Review. Eric completed his DPhil as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, and was a Fulbright Senior Scholar and visiting professor to Stanford University.

Professor Eric Knight is an organisational theory and strategic management scholar. He has published in FT50 journals as Strategic Management Journal and the Academy of Management Review. Eric completed his DPhil as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, and was a Fulbright Senior Scholar and visiting professor to Stanford University.

References

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford.