Once the important paradigm of knowledge management was accepted by both the scholars of the academy of management and executives, knowledge cycle model began to make sense. The focus of this article is based upon the critical role of knowledge cycle model which allows a rich basis to understanding the mechanisms by which knowledge management and operations risk is influenced.

A Birds-Eye View of Knowledge

Knowledge, with its wide classifications, can be classified into individual and collective knowledge. Executives recruit followers based on their individual knowledge which refers to the individual’s skills, prior-knowledge, and proficiencies or sometimes referred to competencies. Collective knowledge, on the other hand, has been defined as “organising principles, routines and practices, top management schema, and relative organisational consensus on past experiences, goals, missions, competitors, and relationships that are widely diffused throughout the organisation and held in common by a large number of organisational members.”1 Thus, collective knowledge is part of the executive’s protocol and comes fairly natural at the higher echelons of the organisation. Executives follow Thomas Davenport and Laurence Prusak’s concern that concludes that if an executive cannot inspire its followers to share their individual knowledge with others, then this individual knowledge is not valuable to the organisation.2 Individual knowledge can, therefore, become a valuable resource by developing an organisational climate of openness for members to exchange their ideas and insights. Executives must create a climate of trust and openness for individuals to share individual knowledge. New technologies drawing on social-software systems through sharing individual knowledge around the organisations can positively contribute to create collective knowledge. Therefore, executives should build an atmosphere of trust and openness and use technology to convert individual knowledge into valuable resources for their organisation to close the performance gap and help organisations prosper.

Knowledge can also be classified using individual, social, and structured dimensions. Executives can categorise followers based on their human knowledge which focuses on individual knowledge and manifests itself in individual’s competencies and skills. This form of knowledge comprises the skills gained by individual experiences, and learned as rules and instructions formulated by executives for followers to use as a guide. Social knowledge, on the other hand, is categorised as individual knowledge that is shared so that it can become collective knowledge. Executives can use structured knowledge that emerges in formal language from annual reports, memos, and other means of communication to be represented as statements. Therefore, executives can classify knowledge in this way so that it emerges at three levels – individual (i.e. human), group (i.e. social) and organisational (i.e. structured).

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Moreover, there is a scientific, philosophical, and commercial side to knowledge that executives should at least be aware of in today’s hypercompetitive business environment. Scientific knowledge is objective and manifests itself as provable and verifiable knowledge or truth, while philosophical knowledge clarifies that “truth is embedded in language and therefore inaccessible.”3 The key for executives is that commercial knowledge, unlike scientific and philosophical knowledge, focuses on enhancing effective performance. Answering the questions executives often ask: “What works?” Based on this view, this kind of knowledge empowers the capabilities of an organisation, and actively improves its competitive advantage in the marketplace. Executives are already aware that commercial knowledge takes an objective approach and can positively contribute to a firm’s performance. The key is how to use this knowledge, enhance it, distribute it, and capture it.

Executives now have a good handle on knowledge in corporations. It is safe to say that knowledge is a component of the more importance competence of a leader which is knowledge management. This next section provides a formalised application that can be implemented by executives when developing knowledge management within companies.

Implementing Knowledge Cycle Model: 3 Simple Steps

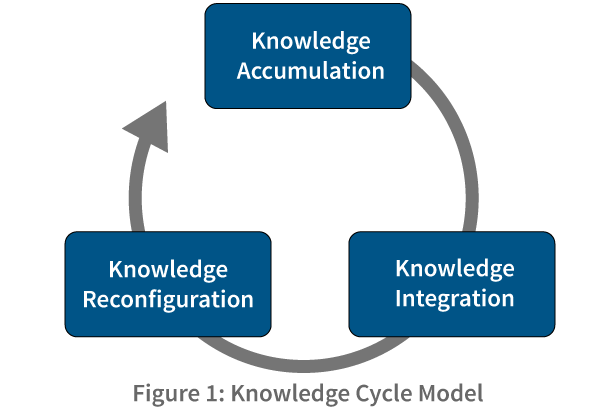

Executives are perplexed by the amount, both depth and breadth, of knowledge management models and applications. A new model that can easily be applied that takes into consideration some of the major tasks that executives must consider is needed. A good example of this, executives can look at three step processes of knowledge accumulation, integration, and reconfiguration. Knowledge management in enterprises can be evaluated by measuring the processes of knowledge finding, integrating and networking. The knowledge accumulation process in knowledge cycle model plays an important role for organisations through acquiring knowledge and information from the external business environment and developing the capabilities to create new knowledge within a company.

A further step to implementing knowledge management is to integrate knowledge within companies. Executives can synthesise new knowledge and information to improve the effectiveness of organisational processes and the quality of products or services. The key here is to internally integrate knowledge so that it is quickly retrievable at the right time and place. Knowledge cannot be used adequately if it takes time to acquire it. Expert systems can provide kiosk like knowledge databanks and intranet searches to retrieve information from the knowledge bank quickly and effectively.

Moreover, competing organisations find ways to share common knowledge so that it can be used by industry alliance when the information is non-specific to a certain organisation. For example, two prominent scholars by the names of John Davies and Paul Warren highlight how organisations must collaborate with other companies, and share their knowledge with them to improve community issues and global problems in a manner that solves problems and creates solutions when necessary.4 This is called “knowledge reconfiguration.” The key kernel for executives is that knowledge is shared with other organisations to recognise the changes occurring in external environments and respond to them quickly and effectively. Figure 1 depicts this knowledge cycle model. The key point in this model is the knowledge accumulation section coupled with integration and reconfiguration to ensure that the knowledge is actually helping the organisation grow both professionally for individuals and profitably for all stakeholders.

Can Knowledge Cycle Model Create A Sustainable Competitive Advantage?

Executives know that discontinuity exists at all levels of product and services and they do not want to find themselves caught off guard and become obsolete. To remain competitive, executives realise that they have to quickly create and share new ideas and knowledge to be more responsive to market changes. Importantly, knowledge held by organisational members is the most strategic resource for competitive advantage, and also through the way it is managed by executives. Executives can enhance knowledge accumulation which is associated with coaching and mentoring activities by sharing experiences gained by imitating, observing and practicing. Executives can, in fact, help followers add meaningfulness to their work in ways enhancing a shared understanding among members to enhance engagement.

In the integration process, organisational knowledge is articulated into formal language that represents official statements. Organisational knowledge is incorporated into formal language and subsequently becomes available to be shared within organisations. Executives have their internet technology departments to create a combination which reshapes existing organisational knowledge to more systematic and complex forms by, for example, using internal databases. Organising knowledge using databases and archives can make knowledge available throughout the organisation – organised knowledge can be disseminated and searched by others. Most importantly, in knowledge integration, organisational knowledge is internalised through learning by doing which is more engaging. It is important to note that executives have found that shared mental models and technical know-how become valuable assets. Organisational knowledge, which is reflected in moral and ethical standards and the degree of awareness about organisational visions and missions can in-turn be used in strategic decision making. Organisational knowledge can be, therefore, converted to create new knowledge that executives can view and implement immediately in managerial decision making. Applying knowledge aimed at providing better decision-making and work related practices and creating new knowledge through innovation.

Finally, when executives agree to share knowledge with other organisations in the environment, studies have shown that that knowledge is often difficult to share externally.5&6 One reason is that other organisations have too much pride to accept knowledge or are apprehensive to expose themselves to the competition. Therefore, executives may lack the required capabilities to interact with other organisations. Learning in organisations is the ultimate outcome of knowledge reconfiguration by which organisational knowledge is created and acquired by connecting knowledge with other companies that want to share successes and failures. This leads to converting acquired knowledge into organisational processes and activities to improve processes that contribute success. Executives can now see that a company’s capability to manage organisational knowledge cycle is the most crucial factor in a sustainable competitive advantage. This core-competitive advantage relies within and among people.

In Conclusion

Executives are aware that activities related to managing knowledge at the individual level and the practices associated with knowledge management at the organisational level are handled at different points on the organisational chart. Therefore, in order for executives to lead between the lines, they need to focus on the interactions among the facets of knowledge to minimise the possible limitations of managing all facets or the business units and components on an organisational chart. Knowledge cycle model focuses on knowledge flows that executives use through embracing the processes of knowledge management for strategic management decision-making. This model takes a task-based approach by translating the management of knowledge into various organisational processes. Accordingly, knowledge cycle model develops a firm-specific approach by which organisational knowledge provides a significant contribution to business objectives through the context-dependent way it is managed. This model can also help organisations identify their inefficiencies in each process, and subsequently recover them on an instantaneous basis which enables executives to prevent further operational risk.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Author

Mostafa Sayyadi, CAHRI, AFAIM, CPMgr, works with senior business leaders to effectively develop innovation in companies, and helps companies – from start-ups to the Fortune 100 – succeed by improving the effectiveness of their leaders. He is a business book author and a long-time contributor to HR.com and Consulting Magazine and his work has been featured in these top-flight business publications.

Mostafa Sayyadi, CAHRI, AFAIM, CPMgr, works with senior business leaders to effectively develop innovation in companies, and helps companies – from start-ups to the Fortune 100 – succeed by improving the effectiveness of their leaders. He is a business book author and a long-time contributor to HR.com and Consulting Magazine and his work has been featured in these top-flight business publications.

References

1. Matusik, S.F. (1998). The Utilization of Contingent Work, Knowledge Creation, and Competitive Advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 680-697.

2. Davenport, T.H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

3. Demarest, M. (1997). Understanding knowledge management. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 374-384.

4, Davies, J., & Warren P. (2011). Knowledge management in large organizations. In J. Domingue, D. Fensel, & J.A. Hendler, (Eds.), Handbook of semantic web technologies, Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

5. Jianbin, C., Yanli, G., & Kaibo, X. (2014). Value Added from Knowledge Collaboration: Convergence of Intellectual Capital and Social Capital. International Journal of u- and e- Service, Science and Technology, 7(2),.15-26.

6. Zehua, Z. (2012). Knowledge Collaboration (KC) and the relationship between KC and some related concepts. Library and Information Service, 8, 107–112.