Artificial Intelligence leadership goes beyond technology

By Prof. Guido Stein, IESE Business School and Alberto Barrachina, Research Assistant

For companies, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the fact that face-to-face is not always the best way to have meetings. Technological devices have made it possible to hold virtual meetings and to have it be the first option for many recruiters who are unaware of the candidate’s health risks and prefer to conduct the interview virtually. The use of tools to conduct video interviews and online assessments, assisted by artificial intelligence (AI) in decision-making, has increased exponentially.

Digital interviews enable companies as well as candidates to have more opportunities. Candidates who would not have been interviewed without this tool can now be considered, and processes that were previously out of reach for many stakeholders can now be applied. On the other hand, AI lacks the keen eye and intuition of the human mind, and the wealth of information that it can provide. However, it also avoids possible biases and replaces them with a quantified objectivity with a scientific basis.

As we will see later, with the help of technology it is possible to analyse tone of voice, word choice, content, eye contact, face configuration, information from multiple sources in their raw state, such as digital footprints on social media or, in the case of internal processes – and with the candidate’s permission – from internal communications such as emails.

Real jobs may be more or less affected by digitisation processes, but what we know for sure and in general is that there are management systems based on AI that cover all areas of Human Resources, from recruitment and selection to employee departures and dismissals. In a 2017 survey, it was already found that 15 per cent of Human Resources leaders surveyed in 40 countries said that AI and automation are already having an impact on their departments, and 40 per cent said they expected both to impact their plans in 2-5 years (Harvey Nash Survey, 2017). Three years later, automation has accelerated, along with other trends such as online purchasing of services and goods, remote working, the storage and analysis of large amounts of data, and redundancy in the management of tasks and the value chain (Candelon et al., 2020). AI is the next logical step in the evolution of companies, as it is useful for adapting to these changes.

Artificial Intelligence in Human Resources is Unstoppable

The classic areas of Human Resources are recruitment and selection, benefits and compensation, performance evaluation and estimation of potential, structure, career and job position design, labour relations, compliance, employee training and development, internal and external communication, analytics and metrics, and departures and dismissals.

Although all of them have significant potential to be automated, many professionals with extensive experience have reservations when it comes to fully adopting new technologies. They put forth reasons such as the fact that some algorithms cannot be replaced by human empathy and intuition. Some have doubts about whether the data can really add anything new to what is already known about workforce dynamics, and they warn of biases due to the quality of the data, and even the quantity necessary to make it meaningful, without considering the legitimacy of its use. On the other side of the divide, there are those who are in favour of applying it for reasons such as the ability to automate repetitive tasks that have little added value, better talent acquisition, faster and more personalised employee onboarding, more efficient and effective training of employees, greater connectivity and technical support in decision-making.

The ability to automate repetitive, low-value tasks.

Examples of such tasks might be compensation and benefits administration, employee questions about procedures and policies, or resume review. To take the last of these, if a previously programmed algorithm is applied, a larger number of resumes can be analysed much more quickly and reliably, significantly reducing human error. The Human Resources team will have more time to provide a series of defined and continuously improving analysis criteria, or to increase the number of responses and interactions with candidates. Job applicants increasingly value getting information on the progress of their application, the time required for each phase of the process, and even the reason for not being selected (Talent Board, 2018).

Better talent acquisition.

Automation makes it possible to compare the skills of candidates with the best-performing employees. On average, a company’s recruiter spends about a third of their work week identifying candidates (Entelo, 2018). In addition, the hiring process generates a large amount of data. If, for example, a company hires 100 workers per year and receives 1,000 applications, the 100 that were chosen and the 900 that were not can generate information about what the company needs and what the labour market can offer at the given moment.

Faster, more personalised employee onboarding.

AI systems can provide information about compensation, benefits, and company policies, as well as personalised suggestions for training and rapid integration into the team. In this way, the length of stay of the employee will improve, thanks to successful onboarding.

More efficient and effective employee training.

Along with training software, AI systems can provide personalised learning paths. The Human Resources department can implement chatbots that offer 24/7 training without interruptions, and with the ability to provide instant and logical responses. According to research by Zoom.ai (Chauhan, 2017), the most active users of automated assistants save up to 25 hours per month, averaging savings of €15,000 on an employee with a salary of €100,000 per year.

Greater connectivity.

As an example, connectivity between candidates, employees, and managers thanks to technology avoids travel and therefore saves both cost and time.

Cognitive support in decision-making.

AI engines can help managers and employees make daily decisions that would otherwise fall on the HR department. For example, when an employee wants to have additional vacation days, the AI system can calculate the probability that their request will be approved or not, without having to consult Human Resources.

In a survey conducted by Oracle among 484 Human Resources professionals (HR Research Institute, 2019), 64 per cent confirmed that AI has a high potential to improve the area of HR. In fact, it was the second most-selected Human Resources function after “analysis and metrics”. The main hiring phases are: design of the job description, opening of the application period, candidates applying, evaluation, and, where appropriate, interviewing of the candidate by the recruiter. All of these phases can be replaced by machines such as chatbots, automated screening tools, or other candidate interaction systems.

The Recruiter’s Perspective

A survey carried out in the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom in 2017, in which 5,179 managers were consulted, showed that only 10 per cent of workers were completely convinced that their jobs could be endangered by AI (Genpact, 2017). Three years later, this has already become reality.

At Amazon, process automation has been a constant, and one of the keys to the company’s success since its inception. However, in 2015, the company found that its recruitment algorithm did not evaluate software developers in a neutral, non-gender way (Kodiyan, 2019). The root cause was that the systems were trained to screen applicants by looking at patterns in resumes submitted to the company over a 10-year period. Most of the resumes that came in had been from men, so Amazon’s system taught itself that male candidates were more likely to be selected for the job. It penalised resumes that included the word “women”, such as “captain of the women’s chess team”, and demoted graduates of two women’s colleges. Amazon adjusted the algorithm to be neutral in this regard. However, the experts indicated that there were other ways of classifying candidates that could be discriminatory. For this reason, both human intervention and new professional capacities that analyse and program these tools are still necessary.

Just as sales automation tools like Salesforce didn’t make sales reps obsolete, a similar trajectory is anticipated for recruiters. The real challenge is how to improve employee talent and training. Only 38 per cent of companies offer training programmes for workers (Genpact, 2017). Technical skills such as coding, statistics, and applied mathematics remain very important, but “soft skills” such as adaptability, critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity are key factors in selection. Possibly, soft skills are the most complicated part to identify in the evaluation of candidates, as well as being the differentiating element between professionals with very similar technical profiles. If, for example, 1,000 resumes are received for a job, of which 25 are selected, the technical level will be very high and the selection of the candidates will be made based on their best suitability for the company. Therefore, a human profile with a clinical eye is necessary to obtain and interpret this non-visible information from the interviewee. A large number of companies do not have a selection “manual” that tells how and where to find candidates. Recruiters are examining the interviewee, interpreting and experimenting with their tools and skills according to their personal experience. However, the rapid evolution of technology will increasingly develop a combination of people and machines that offer decision-making support (Pin et al., 2020b).

The Candidate’s Perspective

Candidates and employees in general expect not only a job, but also a career that can be planned out. However, according to data from employment offices in the United States and Europe, the trend of decreasing time spent working at a company is growing strongly.

The last two generations, millennials, born between 1985 and 2000, and Gen Z (a.k.a. “centennials”), born after 2000, value, first of all, the activity they are going to carry out, knowing how their professional career is going to evolve, and what type of company they will work for – what their values and culture are (Stein et al., 2018). Unlike the baby boomer generation, born between 1945 and 1964, compensation is not a primary reason for leaving a job (Stein and Mesa, 2020). For millennials, if they are not having fun and learning by collaborating in dynamic environments equipped with new technologies, they will look for other career opportunities in companies that are “cool” or that have a well-defined employee brand or employer brand (McCracken et al., 2016).

Younger candidates seek information one to two months before applying to a job (Basu et al., 2019), mainly on the company website, but also on LinkedIn, search engines, through contacts who work at the company, Human Resources departments, headhunters or employment portals such as Glassdoor, which allow employees or former employees to publish information about the company that could previously have been considered confidential. Information on how the selection processes are carried out, the difficulty level of the interviews, the salary range by job category, and the pros and cons of working for the company are publicly accessible. If the company does not proactively maintain its employer brand, its attractiveness to younger talent will decrease considerably. If faced with a poor assessment, the External Communications department will have to devise strategies such as publishing positive comments or clarifying the negative ones transparently and quickly.

Artificial Intelligence and Its Components

If the Human Resources department considers it necessary to make changes to their processes, they must know the basics of AI first-hand, the problems that arise when recruiting talent, the technologies available for each phase of the selection process, and the available and most affordable offering on the market.

The concept of artificial intelligence is very broad and includes several more-specific terms, such as:

- automated learning or machine learning

- natural language processing

- deep learning

- neural networks.

According to the definition by the Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española), artificial intelligence is “the scientific discipline that deals with creating computer programs that execute operations comparable to those carried out by the human mind, such as learning or logical reasoning”.

Machine learning is a type of AI that gives computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed.

Natural language processing refers to the computer’s ability to understand human language as it is spoken. Natural language processing algorithms use machine learning to learn syntax rules by analysing large sets of examples.

Deep learning can be thought of as a series of machine learning decisions. The results of one decision inform the analysis of the next. The number of data processing layers required for the process is what inspired the term “deep”. To achieve a higher level of accuracy than machine learning can achieve, deep learning programs require access to vast amounts of training data and processing power.

A neural network is a hardware or software system inspired by the functioning of the human nervous system. The network is made up of a set of neurons connected to each other through a series of links.

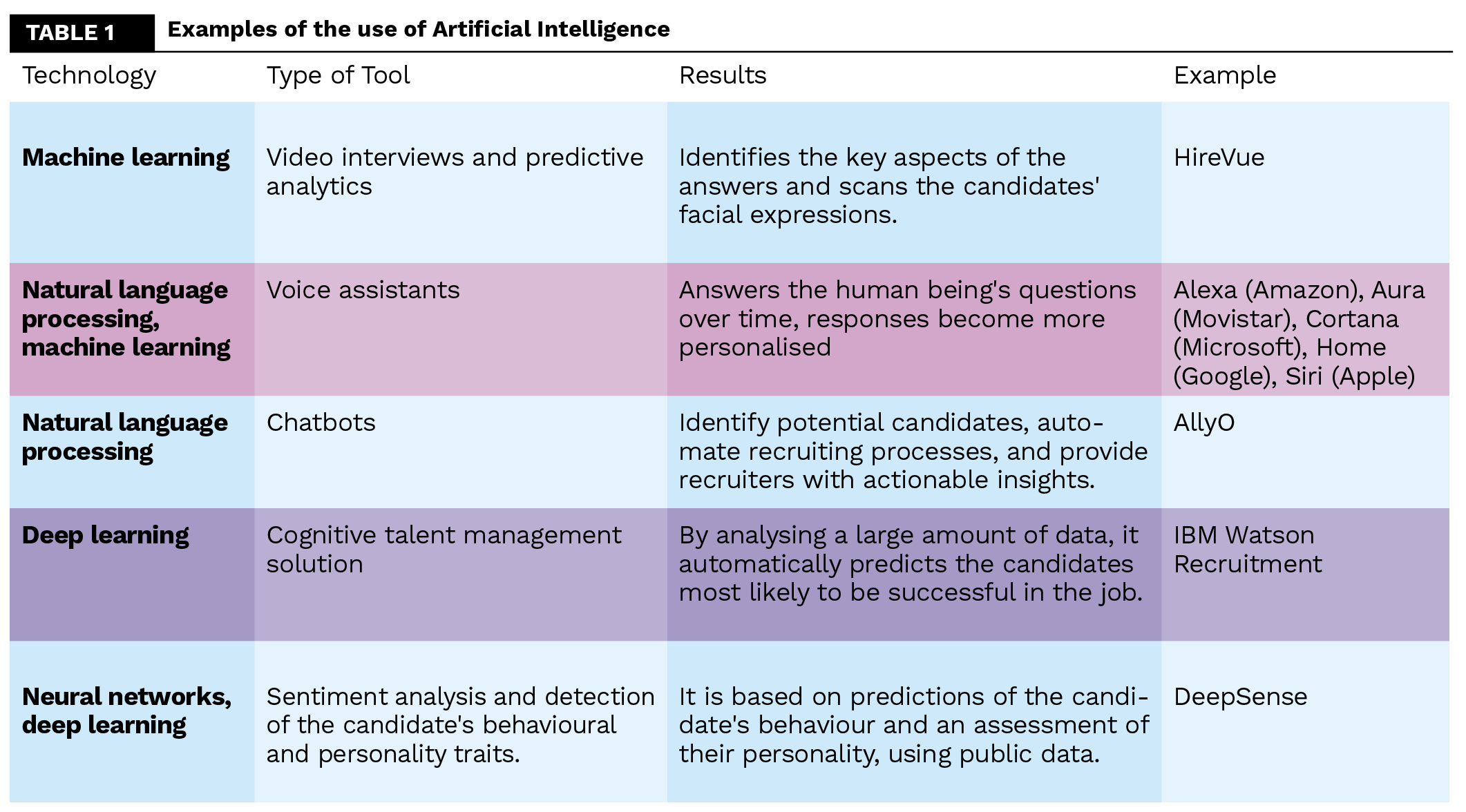

To better understand how these technologies work, table 1 shows each of them, along with the type of tools, results and real examples of the use of AI in the selection and recruitment phase.

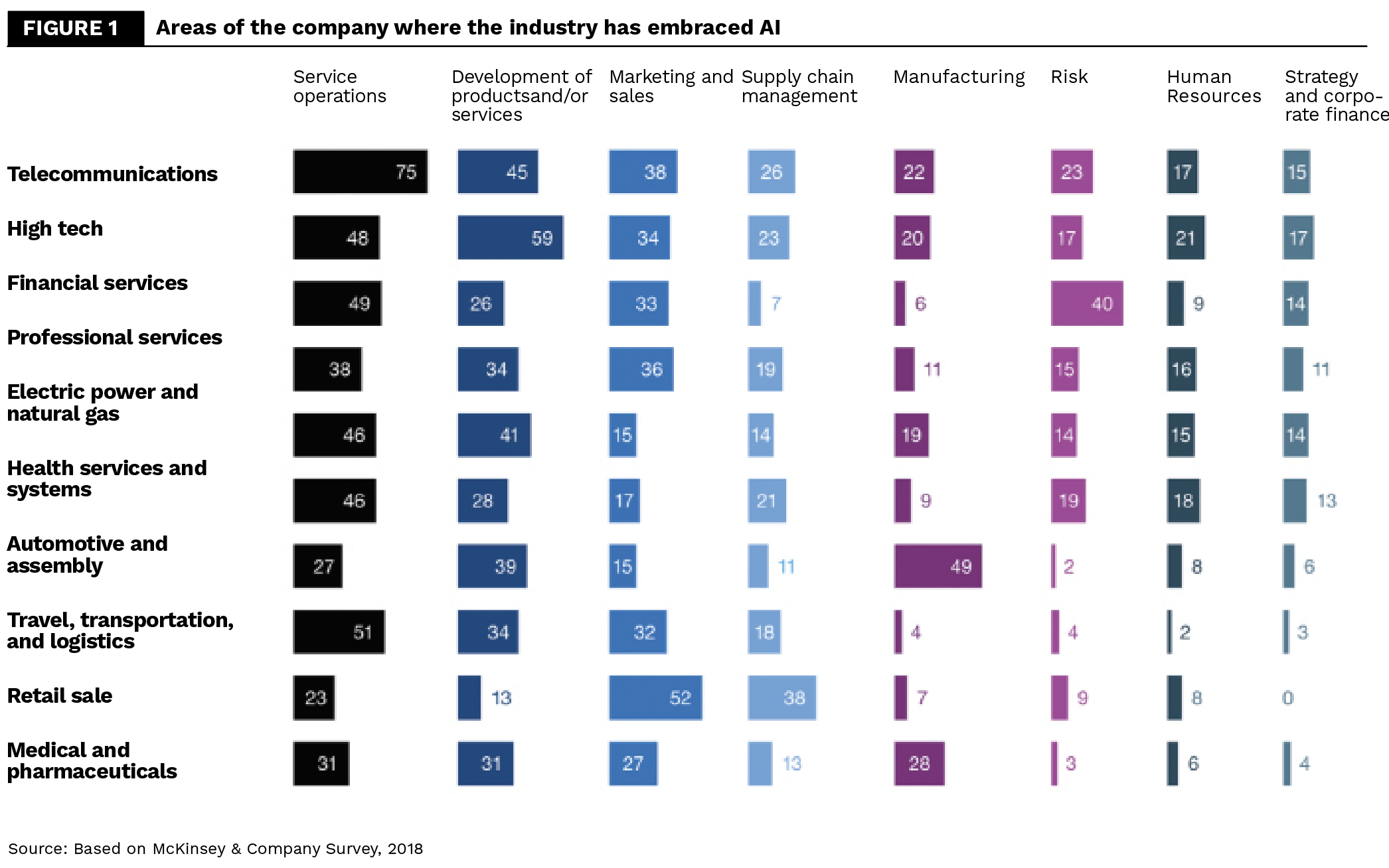

If the general adoption of AI by industry is analysed (see figure 1), the telecommunications, high tech and financial services sectors are the most prominent, although in the Human Resources area, the order varies slightly – the high tech, health systems and services, and telecommunications sectors are those which have a higher degree of automation (McKinsey & Company Survey, 2018). The main reason why high tech and telecommunications companies such as Google, Amazon, Telefónica, and Netflix use automated tools to a greater extent is the difficulty of finding and retaining highly qualified talent among profiles such as data scientists and developers. In the case of the health systems and services sector, the main factors are the progressive ageing of the population, which brings with it a greater burden for medical professionals, and the retirement of nurses, which is creating a large number of unfilled vacancies.

Sectors with a higher demand for profiles with AI skills include high tech, professional services, and financial services. The increased demand for these skills is associated with higher market capitalisation, greater cash holdings, and higher investment in R&D. All of this is consistent when combined with complementary investments in infrastructure, skills, and processes (Alekseeva et al., 2020).

AI Systems in Recruitment and Selection

Access to digital devices and the ease of applying for certain jobs has caused the volume of applications in relation to job offers to increase exponentially for all types of positions. Consequently, recruitment and selection offer a wide variety of opportunities for automation through AI technologies, from candidate screening to resume-to-job matching. In 2018, there were about 70 different technologies that could be used for recruiting automation. Two years later, there are countless. The AI systems that are having the greatest impact are those related to the adaptation of the candidate to the job, through the provision and analysis of data, the rediscovery of talents, facial recognition, the analysis of emotions, verbal communication and interaction, and chatbots or conversation bots (Eubanks, 2018).

The Suitability of the Candidate for the Job

The suitability of the candidate for the job (candidate matching) has been verified historically through the identification of keywords that appear in the resume and that coincide with the job ad. However, it is necessary to make additional considerations that analyse the real abilities of the candidate. There are tools, such as video detection, that allow the recruiter to analyse the tone, the use of words and even eye contact. On the technical side, there are systems that quickly evaluate the candidate, for example in the application of a certain programming language associated with the position or in performing assessments. Resumes are stories of everyone’s professional experience told differently, which can hide certain skills that the human eye can detect. There is empirical data that allows us to affirm that the closer Human Resources professionals get to making the decision, the more necessary it is for the human mind to help the system to filter the candidates in the applicant pool.

An example of an assistant that provides information to the candidate about roles within the company that match their experience and skills is IBM Watson Candidate Assistant. Previously, the first contact between recruiters and candidates would be during the job interview. Nowadays, during the job search phase, the candidate can receive personalised advice from a chatbot that provides information to adjust and limit their search to specific roles. The result of this implementation has been a greater conversion of high-potential candidates to the roles offered by IBM. On average, the company receives 7,000 resumes daily and the use of new technology enables a search conversion of 36 per cent, compared to 12 per cent received by a traditional employment portal. In addition, it has been possible to reduce the hiring time by detecting the ideal candidates for the position more quickly.

Data Provision and Analysis

The provision and analysis of data allows access to a much larger number of candidates, whether they come directly from consulting companies or through the sourcing of external talent data, so that recruiters can contact them directly.

The tools can be databases connected to the company, or external ones. An example is the intelligent search tools that use keywords to find candidates according to the needs of the company. Currently, the main database for companies is LinkedIn, which offers a wide range of candidates for recruiters and headhunters. The LinkedIn Recruiter Tool uses machine learning to improve the recommendation engine. One of the technologies employed in the product is candidate responsiveness, benefiting those who are most responsive. Some of the questions included in the algorithm are: How receptive has the candidate been when contacted by the recruiter on previous occasions? How responsive has the candidate been when being contacted by recruiters, companies, or industries? Is there any recent job search activity? Other companies that are developing selection algorithms are Google and Microsoft. In 2016, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella introduced Cortana’s AI integration with LinkedIn data, so that a conference or webinar organiser could plan content by getting to know their attendees better by visiting their profiles in this online professional network. Google, on the other hand, has developed the Job Search on Google product, implementing machine learning to improve the candidate’s experience during the job search. These are already almost “prehistoric” milestones in the sector.

However, machines can miss suitable candidates. For example, if you’re looking for software developers, you may be missing out on dozens of variations and specialities, such as front-end developer, software tester, or specialist in specific programming languages. Therefore, when the automated job search system has previously processed this type of job, it will have connected other skills or similar positions of the candidates through machine learning. This functionality may not be as useful for a senior recruiter with extensive recruiting experience, but for a junior profile it might be very helpful. Additionally, once the job listing is published, automated systems can automatically search for potential candidates and contact them directly with an automated message. This phase undertaken by a human being can require between eight and 30 hours for a given job, depending on how specialised it is.

With IBM Watson Recruitment, the cognitive system increases recruiter efficiency by highlighting job priorities that demand the most attention. It works with applicant statistics or automatic qualification by analysing factors such as the length of experience in relevant roles, the size of the companies that hired them, and the prestige of the university degree.

Talent Rediscovery

The rediscovery of talent takes advantage of a database with valuable profiles that have already been registered. The advantage is that, after a few years, you can find emerging talent that has been trained in an area of interest. The reality is that there are a huge number of resumes that have been accumulated over the years in a company and that have not been reviewed. If, for example, a company has published 100 positions, there can easily be 25,000 candidacies that have not been analysed. Many of these profiles may be out of date, but there are AI systems that use algorithms that identify patterns of success in the selection process of candidates who were ultimately not selected.

Rediscovering talent also means that all the candidates who have applied receive a response from the company. If virtual friendliness is maintained, potential candidates can be contacted again in the future. Eighty per cent of job applicants say they would not reapply to a company that did not notify them of their application status or did not give them a final response (Career Builder, 2018).

Facial Recognition

Through algorithms, facial recognition tools provide recruiters with the ability to process the video content of the interview. One of the elements that the AI can recognise is whether the candidates are looking at the camera or reading a script. By observing the position of the eye and the direction in which it looks, the system can recognise cheating. Above all, it is useful for tests that the candidate performs from home, without the supervision of a recruiter.

Another element is analysing the candidate’s micro-expressions. The momentary and involuntary expressions that appear on the human face can help robots identify the personality or thinking style of the person being interviewed. Furthermore, it helps the recruiter analyse the emotional reactions to each interview question, specifying how honest or enthusiastic the interviewee has been in their response. Companies such as Unilever already use this technology, and it has made it possible to interview a large number of candidates, which would not have been possible otherwise (see the Unilever case in the Exhibit). These systems are not only available to companies, they can also be used by candidates preparing for their interviews by providing predetermined questions, receiving reports on their facial expressions or personality styles and, by the same token, improve their performance in the final interview.

The final assessment of the candidate by the AI system can be based on a comparison with the best-performing employees of the company. If, for example, a candidate applies for a sales manager position, their facial expressions will be compared to benchmarks in the sales area. This method ensures that the company’s performance level is maintained or even improved with the new talent (Schellmann and Bellini, 2018).

Verbal Communication and Interaction with AI

Automated chatbots or conversation bots would provide us with automated answers to user questions. The candidate could resolve questions about available job opportunities, possible professional careers, and advice on how to improve their own career. Fifty-eight per cent of job seekers are comfortable interacting with AI applications, and more than 60 per cent are happy to interact with chatbots to answer initial questions and schedule interviews with recruiters (Allegis Global, 2017). Candidate questions can be about salaries, job specifications, company information, the recruiting process, work culture and environment, chatbot-related information, or more general questions.

Another functionality that robots can provide is the analysis of elements such as the tone of voice or the set of words used. To do this, “smart” speakers can be integrated into meeting and work spaces to listen to conversations a posteriori and provide more thoughtful insights. What if the head of the HR team could listen to their employees’ interviews and then give them ideas on how to improve results? Would it improve talent acquisition?

Analysis of the Emotions and Personality of the Candidates

The analysis of emotions of the candidates allows analysis of large amounts of text and classifying it according to the disposition they show. The systems combine natural language processing with machine learning. The analysis can use unstructured texts from conversations, emails, and content that they have published on social media or on their website. If someone writes, for example: “I didn’t like my previous job because it didn’t allow me to develop my professional career,” the machine will associate it with negative feelings, whereas if they write, “Throughout my career I have worked with great teams,” it will be associated with a positive feeling.

There are AI systems that compare the resume with the candidate’s social media, such as LinkedIn, Twitter or Facebook, identifying personality traits that help recruiters make decisions about compatibility with the job or company culture (Schellmann and Bellini, 2018).

The Potential Biases and Lack of Privacy of AI Systems

Algorithms and automated systems for candidates and companies can become black boxes whose inner workings are a mystery. When one of these services is contracted, it is necessary to understand how it works and what biases are associated with it, because it is the human mind that programs the algorithm and has it make automated decisions.

AI systems can make the mistake of considering patterns of facial expressions that do not correspond or are not necessary for the job that candidates are looking for. Thus, the recruitment format is not able to select the employees who can best perform the job. Let’s take for example, the case of a young Korean who recently graduated from the University of Illinois and who had more than 30 interviews, of which almost half were conducted by a robot. He did not get past the first phase in any of them. However, he was hired as a junior credit analyst at a local bank in Chicago and, according to his boss, is one of the five best young people who have joined the bank in the 30 years of his professional experience (Schellmann and Bellini, 2018). A second element is the lack of privacy in this type of recording, so the employee or candidate must know what personal data is being used and give their prior consent.

To effectively enjoy the benefits of automated hiring, a hybrid approach between human and machine should be established, followed by labour and administrative legislation in line with the changes in process automation. This requires collective bargaining to establish data collection standards that guarantee equal opportunities in employment (Ajunwa, forthcoming).

Along these lines, in 2020 the European Commission published a white paper that contains the guidelines for regulating AI and eliminating possible bias, the suppression of dissent, and the lack of privacy. In it, the Commission recommends ensuring that AI systems are trained on representative data, that companies keep detailed documentation of how algorithms were developed, inform people when they are interacting with AI, and the need for human oversight of these systems (Chen, 2020). In some cities, such as New York City, a bill has even been introduced that governs the sale and use of any automated employment decision tool. Companies selling these AI systems must provide an annual bias audit to the buyer. Additionally, the bill requires recruiters to notify the candidate of the use of AI technology to assess their application within 30 business days (Forman et al., 2020).

The Application of Automation in Everyday Business Affairs

The main barriers or obstacles for companies (see figure 2) have to do with the lack of budget for investing in new technologies. The company must have sufficient cash and liquidity to assume not only the costs of the technologies, but also the training of professionals in skills to manage AI. The second concern is the lack of Human Resources professionals trained to use the systems. Leading tech companies such as Google and Amazon are vying to attract this scarce talent in light of this new latent demand.

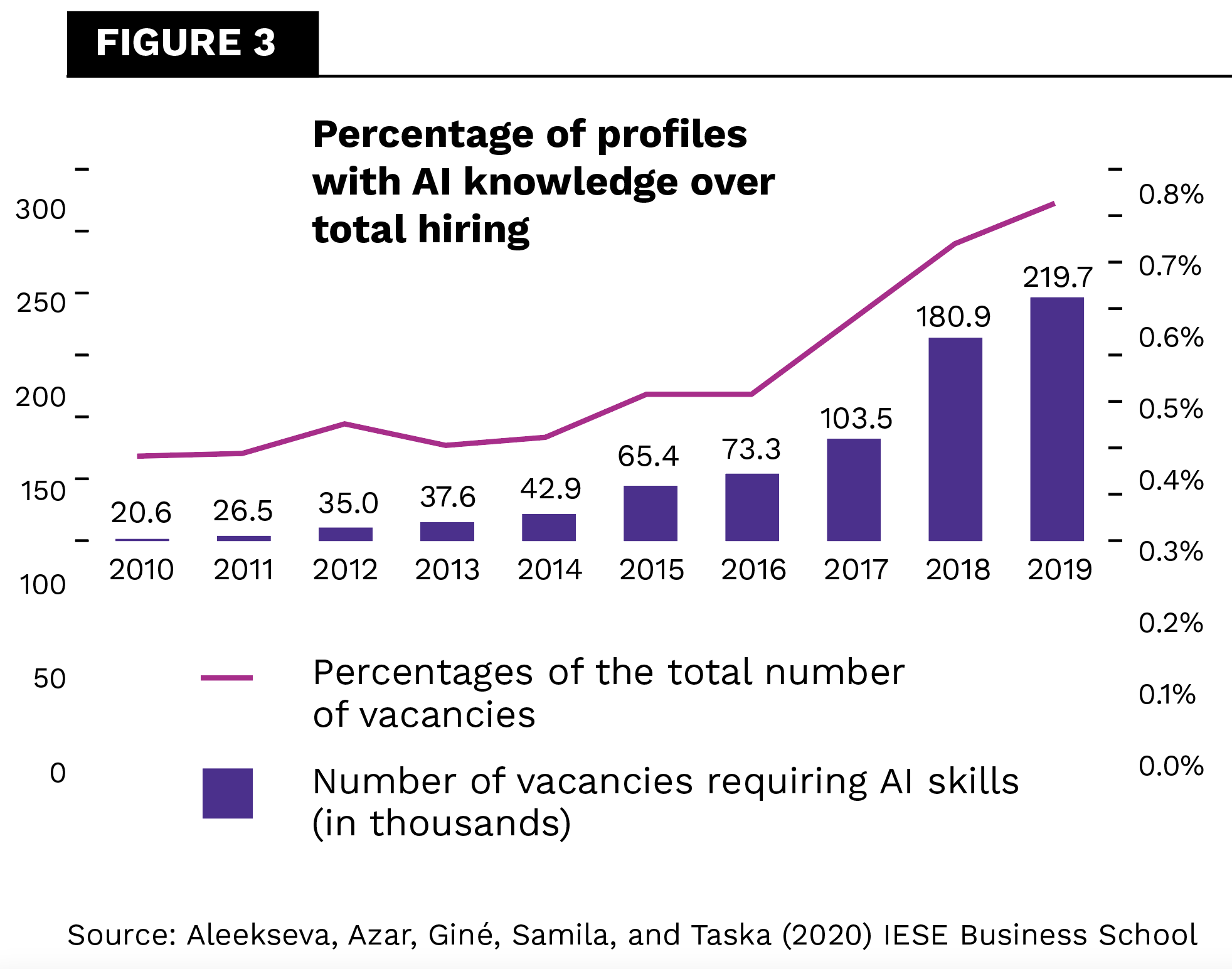

The general hiring trend has seen a large increase in the recruitment of AI-savvy personnel (see figure 3). In addition, there is a difference in salaries for vacancies that require AI and those that do not, with a salary increase of up to 51 per cent. In managerial positions, the highest salary premium is for those with this type of skill (Alekseeva et al., 2019).

Small and medium-sized companies have a harder time recruiting and training the necessary talent, so they are more reluctant to adopt new systems. The third reason is the lack of confidence that AI can achieve a considerable improvement in the areas of Human Resources, mainly because of the two previous reasons, but also due to a certain resistance to change in the organisation. Historically, personal intuition and experience have been the most reliable skills compared to machines or automated systems, due to their biases and, in many cases, they turn out to be black boxes for users, because they are unaware of their internal functioning (HR Research Institute, 2019).

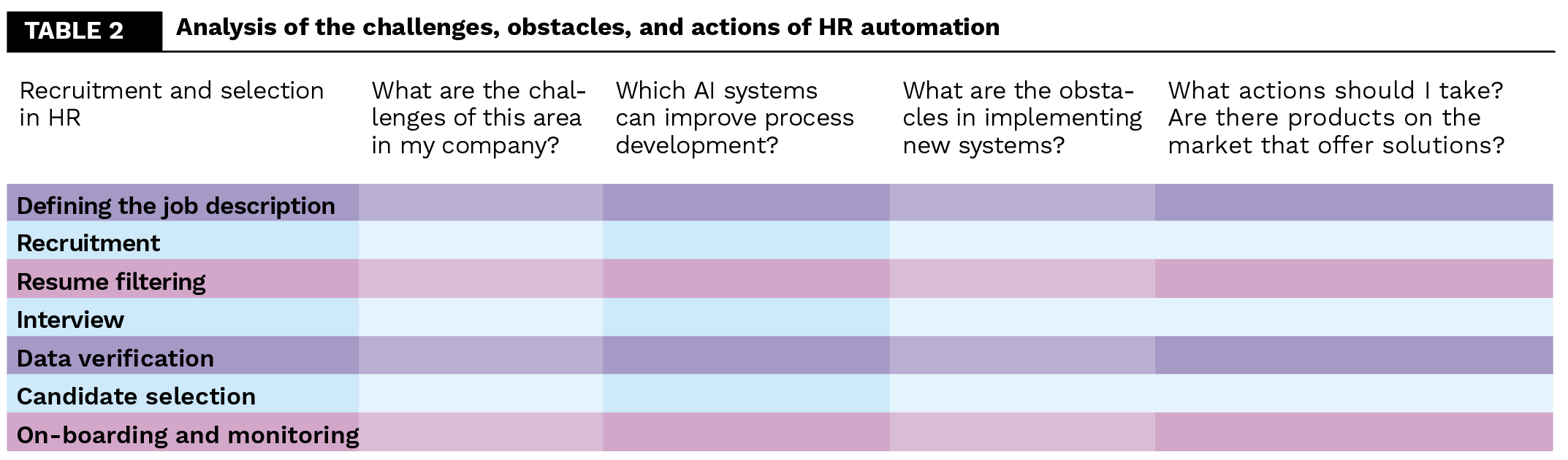

Table 2 shows a method for identifying recruitment and selection areas that can be automated. When the Human Resources department thinks about inserting new AI systems, it has to ask questions like these: What tasks are executed most effectively 24/7? Which processes would be better for running on a large scale? What elements would benefit from being consistent? What would be possible, in selection and recruitment, if we go beyond our current limits? (Guenole and Feinzig, 2018).

In the area of recruitment, it would improve the identification of candidates that match job requirements and compile lists of qualified applicants. In the filtering area, it is expected to prioritise resumes and applications that most closely match the requirements of the position. In terms of interviews, the aim is to speed up the hiring process. In the selection area, it would be tasked with filtering resumes more efficiently, helping to adapt the skills and abilities of the candidates to the labour needs of the company, to carry out rapid training and insertion (HR Research Institute, 2019).

By using table 2, the reader can weigh up whether or not it is necessary to implement changes using new AI technologies in the Human Resources area of their company. The first column presents all the areas that concern the selection and recruitment phase. The next asks about the specific challenges in each area. The reader should ask relevant questions, analysing the problems or opportunities that, if solved, could generate significant value. The third column provides a practical application of what kind of AI systems can improve the development of each process and if there are companies that offer products on the market. A review of the available tools should be carried out. The fourth column serves to analyse the internal obstacles that exist within the organisation to implementing these systems, and the external obstacles caused by the legislative, cultural, economic, and political context. The last column invites a personal and complex analysis of the power and ability to influence the employee or senior manager within the organisation, the information available to them about the AI tools available on the market and the needs of the organisation, the individual and common interests in the Human Resources department and the rest of the company, and the type of relationship that can be established with other employees after the initiatives have been taken.

Summary

The incorporation of automated processes is a necessity for companies to save costs and time, and allow workers to carry out value-added activities. However, the recent pandemic has meant that, in most cases, companies do not have the financial resources and sufficient data available, nor the necessary talent to optimise processes with AI systems.

In the selection and recruitment area, the recruiter will not lose their job due to the appearance of machines that can automate certain tasks such as the analysis of resumes, but rather there will be a slow transition to new jobs that require new technological and personal skills. In general, younger candidates prioritise professional development and job content, so they will be more willing to train in these new technologies. But the company will also need to work on its employer brand to attract this type of talent.

AI has been developing at a global level more rapidly in the last decade, already being able to imitate, through neural networks, the functioning of the human brain and to learn by itself. The results in the selection and recruitment area have been the numerous tools that use AI to improve the candidate’s match with the job, provide better data analysis, rediscover new talent, facially recognise the candidate, analyse their emotions and communicate and interact verbally through chatbots or conversation bots.

However, these machines are still at an early stage of their development and make mistakes – just like humans – such as certain biases in data analysis, not properly recognising some facial expressions, or not responding appropriately to the needs of the person. European legislation and some cities have proposed a first attempt at regulation through greater transparency from vendors to customers about the operation of the algorithms’ black boxes.

The potential of these systems is undeniable, although their development and accessibility may be more limited and unequal with respect to the entire business fabric. Large companies are already implementing these tools and increasingly automating their processes, which is why it is considered necessary for the Human Resources department and management in general to proactively weigh up the management challenges posed by AI systems and manage them properly – leading a future that has already arrived.

Final Considerations

Technology enables access to huge amounts of information about oneself and about others, and improves communication and contact in immediacy and frequency. Nevertheless, it would seem that, in general, the possibility of doing so does not serve to encourage knowing oneself, self-awareness, and, therefore, maturity. Today, a digital maturity is needed, which is the same as always but updated, because becoming a digital organisation entails a tectonic movement in the activities of managers and professionals, in their individual behaviour and in how they relate to each other inside and outside the company. It’s not just about having powerful AI tools to use with customers, processes, products, services, and (as described above) candidates. It is imperative to refine a culture at the level of digitisation that guides us in our process of approaching transformation.

Exhibit

Source: Unilever & HireVue, 2019.

About the Authors

Guido Stein is a Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organisations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance). Prof. Stein is a consultant to owners and management committees of companies. Member of The International Academy of Management and the International Advisory Board MCC (Budapest) and is a collaborator with People and Strategy Journal, Corporate Ownership & Control, Harvard Deusto Business Review, The European Business Review and Expansion. Prof. Stein’s books in English include “Managing People and Organisations: Peter Drucker’s Legacy”, “Now What? Leadership and Taking Charge” and co-author of “Keys to Leadership Success”. He is now working on a book, “Ambidextrous Negotiator” with Kandarp Mehta.

Guido Stein is a Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organisations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance). Prof. Stein is a consultant to owners and management committees of companies. Member of The International Academy of Management and the International Advisory Board MCC (Budapest) and is a collaborator with People and Strategy Journal, Corporate Ownership & Control, Harvard Deusto Business Review, The European Business Review and Expansion. Prof. Stein’s books in English include “Managing People and Organisations: Peter Drucker’s Legacy”, “Now What? Leadership and Taking Charge” and co-author of “Keys to Leadership Success”. He is now working on a book, “Ambidextrous Negotiator” with Kandarp Mehta.

Alberto Barrachina is a Business Intelligence Analyst at PowerShop in Madrid, Spain. He is highly costumer-oriented, multitasking and results-driven, empowered by an international and entrepreneurial mindset, and with a sincere passion in business intelligence, content strategy, and digital business strategy. He is a research analyst who’s been collaborating with Professors Guido Stein and Kandarp Mehta.

Alberto Barrachina is a Business Intelligence Analyst at PowerShop in Madrid, Spain. He is highly costumer-oriented, multitasking and results-driven, empowered by an international and entrepreneurial mindset, and with a sincere passion in business intelligence, content strategy, and digital business strategy. He is a research analyst who’s been collaborating with Professors Guido Stein and Kandarp Mehta.

Bibliography

AJUNWA, I. (forthcoming). Automated Employee Discrimination. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology. papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3437631

ALEEKSEVA, L., Azar, J., Giné, M., Samila S., and Taska, B. (2020). The Demand for AI Skills in the Labor Market. IESE Business School.

ALLEGIS GROUP. Top Companies Spend 63% More Time Evaluating the Effectiveness of Their Recruitment Process, According to Allegis Group’s Global Talent Advisory Survey.https://www.allegisgroup.com/en/about/press/allegis-group-global-talent-advisory-survey-2017-launch

BASU, N., Ignatova, M., Reilly, K., and Schnidman, A. (2017). Inside the Mind of Today’s Candidate. 13 insights that will make you a smarter recruiter. LinkedIn Talent Solutions. business.linkedin.com/content/dam/me/business/en-us/talent-solutions/resources/pdfs/inside-the-mind-of-todays-candidate.pdf.

CANDELON, F., Reichert, T., and Duranton, S. (2020). The Rise of the AI-Powered Company in the Post Crisis World. BCG Henderson Institute. www.bcg.com/publications/2020/business-applications-artificial-intelligence-post-covid.

CAREER BUILDER (2018). The Career Builder Survey.

Chahan, A. (2017). Zoom.ai + SimplyInsight: Deeper Insights to Help you Work Better https://futureofwork.ai/zoom-ai-simplyinsight-deeper-insights-to-help-you-work-better-5b5ce3d75697

CHEN, A. (2020). The EU Just Released Weakened Guidelines for Regulating Artificial Intelligence. MIT Technology Review. www.technologyreview.com/2020/02/19/876455/european-union-artificial-intelligence-regulation-facial-recognition-privacy.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2020). White paper on Artificial Intelligence: A European Approach to Excellence and Trust. ec.europa.eu/info/publications/white-paper-artificial-intelligence-european-approach-excellence-and-trust_en.

ENTELO (2018). 2018 Recruiting Trends Report.

EUBANKS, B. (2018). Artificial Intelligence for HR. Kogan Page.

FORMAN, A., Glasser, N., and Lech, C. (2020). INSIGHT: Covid-19 May Push More Companies to Use AI As Hiring Tool. Bloomberg Law. news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/insight-covid-19-may-push-more-companies-to-use-ai-as-hiring-tool.

GENPACT (2017). The Workforce: Staying Ahead of Artificial Intelligence. Dispelling Myths About How People See AI’s Impact on the Workforce. www.genpact.com/downloadable-content/the-workforce-staying-ahead-of-artificial-intelligence.pdf.

GUENOLE, N., and Feinzig, S. (2018). The Business Case for AI in HR With Insights and Tips on Getting Started. IBM Smarter Workforce Institute. www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/AGKXJX6M.

HARVEY NASH (2017). The Harvey Nash HR Survey.

HIREVUE and UNILEVER (2019). Unilever Finds Top Talent Faster with HireVue Assessments. HireVue.

HR RESEARCH INSTITUTE (2018). The State of AI in HR. HR.com.

HR RESEARCH INSTITUTE (2019). The 2019 State of Artificial Intelligence in Talent Acquisition. HR.com.

KODIYAN, A. (2019). An Overview of Ethical Issues in Using AI Systems in Hiring With a Case Study of Amazon’s AI Based Hiring Tool. Research Gate. www.researchgate.net/publication/337331539_An_overview_of_ethical_issues_in_using_AI_systems_in_hiring_with_a_case_study_of_Amazon’s_AI_based_hiring_tool.

MCCRACKEN, M., Currie, D., and Harrison, J. (2016). Understanding Graduate Recruitment, Development, and Retention for the Enhancement of Talent Management: Sharpening “The Edge” of Graduate Talent. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(22), 2727-52. doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1102159.

MCKINSEY & Company Survey (2018). AI Adoption Advances, But Foundational Barriers Remain. www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/artificial-intelligence/ai-adoption-advances-but-foundational-barriers-remain#.

PIN, J.R., Quintanilla, J., Rodríguez-Lluesma, C., and Stein, G. (2020a). Las políticas de dirección de personas en la era digital. DPON-157, IESE Business School.

PIN, J.R., Quintanilla, J., Rodríguez-Lluesma, C., and Stein, G. (2020b). Los problemas éticos en recursos humanos en la era digital: ¿responde el ser humano o la inteligencia artificial? DPON-158, IESE Business School.

RAJESH, S., Kandaswamy, U., and Rakesh, A. (2018). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Talent Acquisition Lifecycle of Organizations. International Journal of Engineering Development and Research, 6(2), 849-56.

SCHELLMANN, H., and Bellini, J. (2018). Artificial Intelligence: The Robots Are Now Hiring. The Wall Street Journal. www.wsj.com/articles/artificial-intelligence-the-robots-are-now-hiring-moving-upstream-1537435820.

STEIN, G., and Mesa, R. (2020). Los comportamientos de la generación millennial desde un punto de vista laboral y económico. IESE Business School.

STEIN, G., Rodríguez-Lluesma, C., and Martín, M. (2018). Una revolución en el núcleo de la organización: los millennials. DPON-144, IESE Business School.

STONE, P., Brooks, R., Brynjolfsson, E., Calo, R., Etzioni, O., Hager, G., Hirschberg, J., Kalyanakrishnan, S., Kamar, E., Kraus, S., Leyton-Brown, K., Parkes, D., Press, W., Saxenian, A., Shah, J., Tambe, M., and Teller, A. (September 2016). Artificial Intelligence and Life in 2030: Report on the 2015-2016 Study Panel. Stanford University. ai100.stanford.edu/2016-report.

TALENT BOARD (2018). The North American Candidate Experience Benchmark Research Report.