By Guido Stein and Marta Cuadrado

In Part One of this article we will address a number of issues related to mergers. First, we will look at the key reasons why companies decide to pursue them and the reasons why many fail. Second, we will consider the inevitable realities associated with mergers. Part Two is available in the next issue.

“Take the right steps; take them quickly enough; prepare people to live with the problems that will remain” – P. Pritchett

The following statement is attributed to Warren Buffet:

“Our method is very simple. We just try to buy businesses with good-to-superb underlying economics run by honest and able people and buy them at sensible prices. That’s all I’m trying to do”.

The aim of this article is precisely to consider the human dimension of mergers and acquisitions and the way these processes impact people. In the substantial body of scientific literature that exists on this topic, authors discuss the rules and “magic” formulas that lead to a successful acquisition, grounding their arguments in empirical evidence.1 One of the first conclusions that can be drawn from examining this literature is that the authors cite a wide variety of empirical evidence in each case, and that this evidence serves to support different, and even contradictory, theses concerning the key aspects and elements of company acquisitions. Rationalisations are made a posteriori and seek to offer rules, or something close to that. They should be taken as broad approximations, but do point in the right direction. As a result, they are perhaps more useful for those whose work involves taking action than they are for academics concerned with scientific rigor.

In Part One of this technical note we will address a number of issues related to mergers. First, we will look at the key reasons why companies decide to pursue them and the reasons why many fail (Sections 1 and 2). Second, we will consider the inevitable realities associated with mergers (Section 3). Part Two is available in the next issue.

Acquisitions affect everyone involved to one degree or another. They are not neutral transactions in any sense: not from a financial, tax, legal, operational or commercial perspective, and especially not in terms of how they impact the people in both companies involved and other stakeholders (shareholders, suppliers, customers, etc.).

For many companies, mergers by acquisition have become a recurrent strategy for dealing with competition, gaining market share, or simply ensuring their survival. Their impact on stock markets is noted within hours, but their consequences for the people who live through them are rarely reflected in the media.

In tackling these issues, we will draw on the experience of managers who have gone through merger processes and ground our discussion in the scientific literature.

1. Mergers and Acquisitions: Why Do Firms Undertake Them?

A merger is the creation of a new company that is formed by combining the assets and liabilities of the merged companies. According to various reports issued by major consultancy firms, over 60% of mergers end up failing in the long term, which results in the companies involved losing ground in terms of their positioning in the market, losing business, and even disappearing in some cases.

The most basic reason for undertaking a merger is to help transform a company’s business operations by incorporating new products, services or talent. In other cases, the aim is to expand certain operations in economies undergoing rapid growth and take advantage of the opportunity they present. Mergers may look like an attractive option since achieving similar results by other means would take more time and effort. In many cases companies also see mergers as a way to increase their market share.

Whether mergers are strategic, financial or operations-related, the reasons that most frequently impel companies to undertake them can be summed up as follows:

1. Pursuit of market leadership: the speed at which certain sectors are evolving leads companies to seek new partnerships in order to acquire customers and avoid being shut out of the market.

2. Geographic diversification: to test the capacity of their business model by gaining access to different sales channels and emerging markets.

3. Financial reasons: to increase cash flow, improve capital structure, or reduce the cost of debt.

4. As a means of increasing capital in order to write down assets and improve the company’s solvency ratio by integrating complementary products and services.

5. Pursuit of production-related synergies (cost reduction, improved income from profits, etc.) or financial synergies (tax benefits, lower cost of capital, etc.).

6. Access to new ideas, technologies and talent.

7. Pursuit of opportunities to increase the welfare and security of shareholders in times of crisis.

8. Personal motivations (ego, achieving power or a higher salary) or speculation by company leaders.

2. Reasons Why Mergers and Acquisitions Fail

According to Professor J. R. Pin, “merger mania” is the excessive use of mergers and acquisitions as a means of achieving business growth and expansion.4 As we indicated in the preceding section, excess cash balances and an interest in pursuing continued growth are some of the reasons that drive companies to acquire other organisations. But are such deals always profitable? Despite the expectation of resounding success that prevails during the negotiation process, the answer is no.

A merger is seen as having failed when in the short term the value of the company has actually decreased rather than increased. The standard figure given for the loss of business after a merger ranges from 5 to 10%, though in some cases it is even higher (see Exhibit 1 above). Why are due diligence5 investigations and other pre-merger reviews unable to foresee such losses?

Mergers and acquisitions entail ‘hidden’ costs or ‘grey areas’. According to some experts, including Shippee,6 these costs arise because the human element – what Shippee calls the “X factor” – is overlooked. The people who make up the organisations involved can play a key role in streamlining the process and mitigating any traumatic effects, helping to tip the scales that measure the success of a merger one way or the other. The right kind of behaviour increases the chances of achieving success in the long term.

The traumatic effects experienced are usually identified as “merger syndrome.” They include mixed feelings – anxiety, frustration, disappointment and uncertainty – as well as tension between individuals and groups in the organisations undergoing the merger. The emotional impact of the change process leads to a slow trickle of key people leaving the company, adversely affecting its day-to-day activity. In a climate marked by internal ‘noise’, lack of motivation, and a sense of unease, people focus on protecting their jobs rather than, for example, taking care of customers. These behaviours result in a loss of business (mainly customers and suppliers) and talent. At the same time, because they are afraid of making mistakes, those responsible for the merger stop taking decisions that, though they entail a degree of risk, are likely to be in the company’s best interest.

People often forget that mergers involve more than just acquiring assets or technology, increasing market share, or incorporating another company’s talent. What makes these processes so complex is the need to integrate two organisational structures and make them work, and to combine different styles, workforces, processes and cultures. This is where the human dimension of the merger becomes so important. Leaving aside that a merger may fail because the company acquired has not been entirely truthful, a study on mergers and acquisitions carried out by KPMG7 identifies the main causes why such deals fail, emphasising that a cultural mismatch between the firms involved can be one of the fundamental reasons. Other causes include lack of defined leadership, poor implementation of the merger plan, resistance to change, lack of employee motivation, poor communication, and loss of key talent. When a merger is undertaken, the aim is to generate sufficient synergies to present the market with a clear, concise argument as to why the merged entity will be more productive and deliver better results in less time. Synergies of this kind are oriented towards cost savings, and due diligence reviews focus on identifying such synergies. Consequently, people and factors with a more qualitative component – aspects that take longer to evaluate and manage and whose economic impact is less apparent in the short term – are not given enough consideration. Capital markets seem to lack the time and patience needed to take these issues into account.

The reflections of the operations manager of a service company that was acquired by a construction company in 2012 illustrate this problem. Though his view is a subjective one, it points to a very real situation:

“Incorporating a service company involved in systems maintenance (X), with quite a lot of technological support, in a company with a purely concrete-and-bricks philosophy is a process which, if not handled properly, can turn into a real train wreck. In X we built a close relationship with our customers (agencies responsible for managing the infrastructure maintained by city councils, Spain’s autonomous communities, and government ministries). These relationships were developed through area representatives and highly specialised teams of technical personnel, organised to deal with both periodic checks and breakdowns in the various systems. I was in charge of the systems for three shifts set up to ensure 24-hour service in every city where we operated. If the controller for the traffic lights at a particular intersection fails, the problem needs to be dealt with urgently and efficiently. The same is true when there’s an incident involving the street lighting in a city or lighting in a tunnel”.

“The two companies had very different working philosophies. The construction firm, which didn’t have a technology department, focused on the profitability of each individual project. Its philosophy was based primarily on the “skill” of its construction managers in obtaining concrete and other building units at the best price and with the shortest possible lead-time. After the merger, X’s area representatives, real sales reps who were very engaged with their areas, were replaced by tightfisted construction managers with an authoritarian leadership style. This had a series of immediate consequences: a strike by technical services, fines and penalties imposed by government agencies due to poor service (breakdowns that weren’t dealt with in a timely manner), unmotivated employees, dismissals, the taking on of replacement technical personnel with little talent and know-how, obsolete control systems for control rooms due to a lack of investment in R&D, and so on”.

Human and cultural factors only start to become the focus of attention when the case for the synergies to be obtained from a merger has been made to the market (and this shift of focus does not occur in all cases). Yet these are the factors most likely to cause deals of this kind to fail. Why are these issues generally not addressed in an appropriate and timely manner? Let’s see what the technical director of an IT multinational has to say:

“After completing three acquisitions my company was itself acquired. All this happened in three years. The point that generated a lot of conflict was the difference in terms and conditions of employment between the two structures. When we were acquired, the incoming company had a collective agreement with more advantageous terms for employees, including better working hours, more vacation time, higher salaries, and so on. We lived with these differences for months and months, which prolonged the agony because it was a constant reminder that we were the ones who’d been acquired. It made us feel like second-class employees. I think the teams could have been integrated more quickly and effectively if, right from the early stages, they’d merged the works councils of the two companies and established a collective agreement with the same terms for all staff. It seems obvious that this was the right thing to do, but the fact is that they allowed this distinction between employees to go on for a very long time”.

Understanding how employees view the new context should not be complicated. However, despite the tools at their disposal, companies tend to:

• carry out due diligence reviews that do not include sufficient analysis of cultural and organisational factors;

• pursue complex strategies that slow down processes and hinder their definition and communication;

• delegate management of the process mainly to experts from the financial area and specialists in legal and tax matters;

• lack the information needed to make operational decisions that contribute to shaping the new corporate structure.

2.1. Can a Merger Be Made More Efficient?

It is difficult to determine the exact proportion of talent that is ‘lost’ after a merger. For one thing, the loss of talent cannot be understood simply in terms of the number of people who voluntarily leave the resulting organisation during or after the process. One also needs to consider the talent that has been the “victim of the synergies” and, most importantly, the unmotivated and disgruntled talent that stays on – that is, people who, though they feel their careers have been derailed and their expectations frustrated, decide for one reason or another not to leave the company. This is a hidden cost and often one that nobody wants to estimate. The following sections offer some suggestions for managing the merger process.

2.1.1. Set Up a Full-Time Interdisciplinary Merger or Integration Committee

This team, made up of representatives from the main areas involved, should serve as a forum where participants can contribute diverse viewpoints. The purpose of the committee, oriented towards implementing the merger, is to focus attention on decisions that provide stability within the company and help create opportunities. To reinforce its authority, the committee should be overseen by a figure (usually from the acquiring company) whose leadership is undisputed. Its role is to ensure that decisions are made on objective grounds and safeguard the interests of all affected parties (see Figure 1 below).

Committees of this kind should seek to:

• communicate what they know as soon as they know it;

• recognise unknowns and set time limits for making decisions;

• treat people fairly and with respect;

• act swiftly to integrate processes;

• bolster the company’s vision, its values, and the goals to be achieved.

Subcommittees for related areas – composed of the most talented individuals from the two firms and reporting to the committee – should also be set up. Subcommittees should manage key information, focusing on matters such as the criteria to be followed after the merger in dealing with specific customers absorbed into the portfolio of the acquiring firm, and how to ensure service is not affected; what human and technical resources are strategically important and necessary; and how to lead teams in an integrated way. The primary objective is to prevent decisions and actions that lead to conflicts that become increasingly intractable as the merger progresses.

2.1.2. Conduct a Comprehensive, Integrative Analysis Before the Merger

The deal should be prepared with enough time to maximise the chances of success and minimise damaging effects. In addition to focusing on financial, commercial, systems-related and operational aspects, adequate time should be devoted to studying the following points in sufficient detail:

The mission and values. It is advisable to put these principles into writing, see how they differ from those of the acquired company, and plan short- and long-term actions that will facilitate the transition from one culture to the other.

The new structure and organisational chart. To the extent possible, plans should specify who management wants to put in each position. It is helpful to have a Plan B for each position and contemplate a dignified exit for those who will be left out.

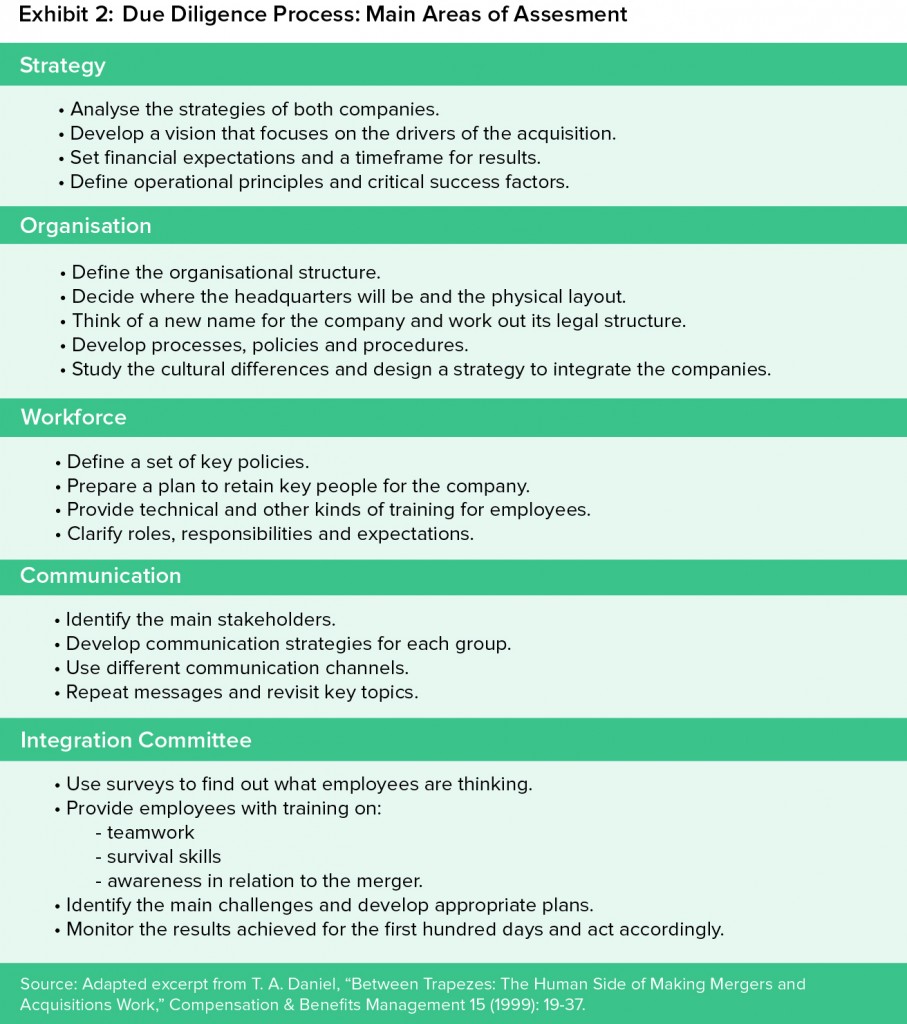

Another aim of these preliminary processes is to analyse possible scenarios and identify hidden costs well before the closing date for the deal. The idea is to carry out a mature, balanced examination of what each company does best in order to subsequently put on the table the operational, business and cultural aspects that lie behind the integration (see Exhibit 2 above).

These analyses need to go deep enough to detect the kind of anomalies that are generally only diagnosed (and their negative effects noted) after arrangements for the merger have been finalised. Figure 2 shows how the intensity of conflicts and the number of incidents is inversely proportional to the breadth and depth of the review carried out. (see figure 2 below).

2.1.3. Intensify Downward Communication

Communication is a key aspect of any merger. If handled properly, it can have a positive impact on the number of jobs. As soon as rumours of a merger begin to circulate, employees and managers tend to start thinking about questions such as “How will my job be affected?” and “Will there still be a place for me?” Communication and human resources departments should therefore take coordinated action that focuses mainly on affected individuals, time frames, the message conveyed and its tone. The same kind of work needs to be done with other stakeholders, including the media, customers, and so on. The communication plan should seek to explain the objective, the stages of the merger, and the circumstances and context for the deal. It should also address the risks involved in a positive way and set out the steps that will be taken to mitigate them. The aim is to reduce the uncertainty due to lack of information that inevitably exists in any merger by acquisition. Particular attention should be given to messages communicated to the customer service department given its key role in ensuring that the merger does not lead to a decline in sales and the loss of customers.

The worst thing about communication problems is that they tend to have a knock-on effect. To ensure the effectiveness of communication during the merger process, the following principles should be taken into account:

• Communication should be quick, honest and frequent.

• Use all available communication channels. Manage online rumors and reactions.

• Choose subjects with care: omitting is also a way of informing.

• Messages should focus on change and progress.

• Involve employees in the process: ask for feedback and use it to make improvements.

• Do not hide the fact that problems will arise. Let people know that problems will be tackled with the help of everyone involved.

2.1.4. Facilitate Internal Mobility

Outplacements can be a way to mitigate the most dramatic effect of mergers: dismissals. In the right circumstances, internal selection processes can be part of the solution. It is advisable to perform an assessment of employees and an analysis of the organisational structure to identify alternative ways of dealing with the overlaps bound to result from the merger. In carrying out this process, the departments involved in the restructuring must also take into account other issues of concern to employees and be able to answer the question “What do I get out of the merger?” For affected employees, the following issues will need to be addressed:

• Position

• Role in the organisation

• Job title

• Boss

• Team of colleagues/collaborators

• Office/workplace

• Pay

• Benefits

• Career

• Future

The Human Resources department’s role is to act as an intermediary

between the company and employees and forestall the emergence of a “winners and losers” mentality.

2.1.5. Support and Rely on Human Resources Management

A merger is a real test for the human resources department. Its level of involvement and performance will show whether or not it is able to rise to the occasion. The department’s role is to act as an intermediary between the company and employees and forestall the emergence of a “winners and losers” mentality. This can be accomplished by applying objective decision-making criteria and proven tools for promoting integration and avoiding arbitrariness. Such criteria help people understand the reasons for the most complex decisions that need to be taken.

3. The Reality of a Merger (by Acquisition) Process

Productivity suffers in so far as people are unclear about their future and must therefore move out of their comfort zone to learn and put into practice new ways of doing things. While it is normal for performance to be adversely affected early on, it is important to act expeditiously and take a realistic approach to managing the situation.

Reality One: There’s Always a Winner.While the proponents of a merger argue, communicate and insist that both organisations come out ahead, the reality is usually quite different: there are, in fact, no mergers of equals, only acquisitions. The acquiring company generally imposes its policy, values, culture and rules. However, it is the acquirer that loses the most by taking this kind of approach: there is always a price to be paid for this kind of ‘ethnic cleansing’ in terms of the mark it leaves on those who remain.

Reality 2: Pain is Inevitable. Nothing Will Be the Same. Redundancy leads to outplacements, reduction of the workforce, and labour force adjustment plans. Sometimes efforts to avoid inflicting pain turn out to be useless and simply delay the realisation of cost synergies and improvements to processes. Although the new company may end up creating jobs in the long term, in the short term there are bound to be dismissals. Change at the personal and organisational level leads to uncertainty and generates a sense of disorientation, a situation that often only improves with the passage of time.

Reality 3: Success Depends Largely on Middle Managers. Assessing key managers should be a focus of attention for senior management and one of the first items on the agenda for human resources during a merger by acquisition. It is middle managers who manage the change while also running the business. Their involvement is essential for a merger to be effective. If they are on board, everything will go better.

Reality 4: Works Councils and Unions Will Be Against the Process. Unless something is done to change the situation – such as entering into negotiations with them before the process even starts – works councils and unions will be part of the problem, not part of the solution. Effective negotiation depends on understanding their position on the personal level and at the level of the group they represent. Their critical needs must be recognised and gradually met in exchange for them providing adequate support for the progress of the merger. Finally, if a deadlock is reached, they should be offered a dignified exit.

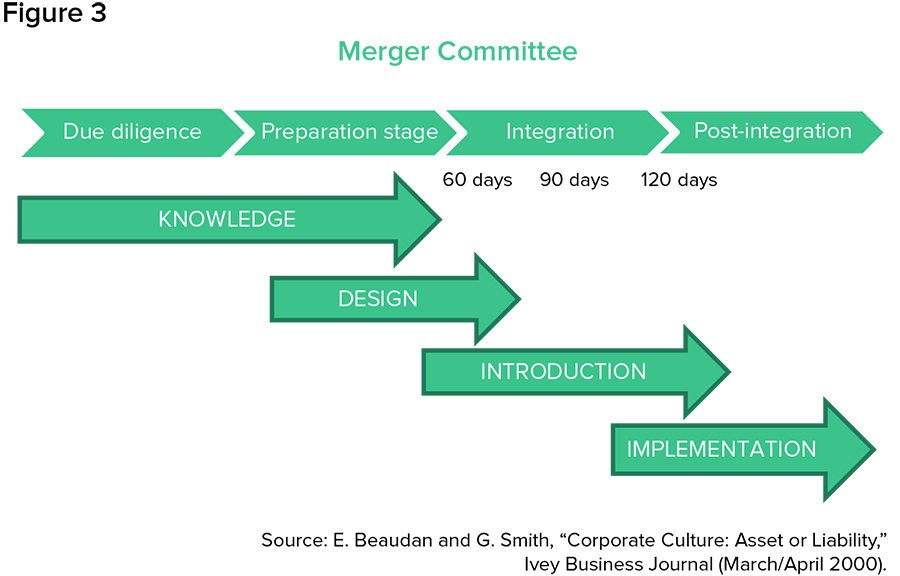

Reality 5: Cultural Integration Isn’t Achieved Only Through Friction. The people involved in managing a merger by acquisition usually assume that once people from the two organisations are working together in the same place cultural integration will happen over time and with a certain degree of ‘friction’. However, it is not just a matter of time: companies must fully engage in the process, and management must take action based on rigorous, straightforward procedures. If the leaders of a merger act with integrity, this reduces uncertainty and pain, leading to an increase in efficiency (see Figure 3 below).

Reality 6: The Best People Have Opportunities Elsewhere. The best people also tend to take the bull by the horns; they do not wait for events to unfold before negotiating with other companies. If the goal is to keep them in the company, it is important to act quickly.

*Part 2 of this article will be available in the May/June 2016 edition of The European Business Review

About the Authors

Guido Stein is Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organisations at IESE Business School, Spain. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance).

Guido Stein is Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organisations at IESE Business School, Spain. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance).

Marta Cuadrado, Research Assitant at IESE Business School.

References

1. A good example is the map offered by Paine and Power in “Merger Strategy: An Examination of Drucker´s Five Rules for Successful Acquisitions,” Strategic Management Journal 5 (1984): 99-110.

2. P. Fernández and A. Bonet, “Fusiones, adquisiciones y control de las empresas,” Arbor: Ciencia, pensamiento y cultura 523-524 (1989): 39-60.

3. N. Zozaya, Las fusiones y adquisiciones como fórmula de crecimiento empresarial (Dirección General de Política de la PYME, 2007).

4. J. R. Pin, “El lado humano de las fusiones y adquisiciones: el modelo antropológico frente al culturalista”, FHN-208, IESE Business School, Barcelona, 1990. Available on IESEP (only in Spanish).

5. Due diligence is the preliminary analysis or audit performed to assess a company’s assets ahead of a possible acquisition.

6. KPMG (2011), “Whitepaper on Post Merger People integration,”

7. https://www.kpmg.com/IN/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/Post%20Merger%20People%20Integration.pdf.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)