By Andrew Binns and Wendy Smith

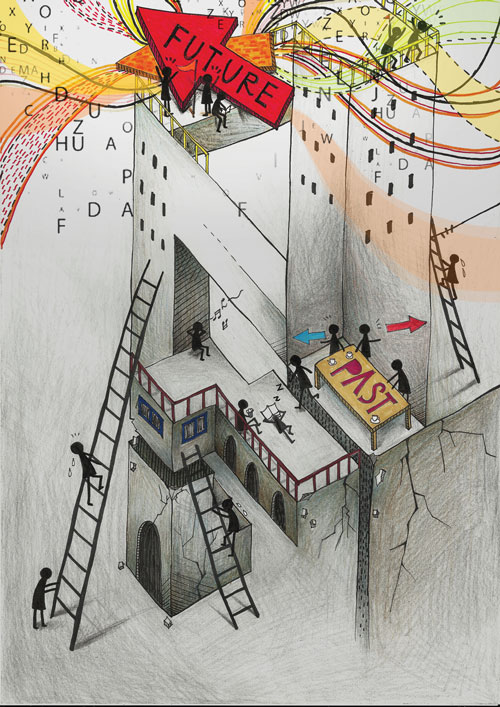

When a business faces the paradox between transforming for the future and securing its current market position, leading change requires a new toolkit.

The high-profile bankruptcies of firms such as Blockbuster Video and Borders bookstores underlines that a slowing economy leaves little space for out dated business models. Unable to keep up with the pace of digital competitors such as Amazon, Google and Netflix, they crashed to an early demise. That these two relatively young, once innovative firms were unable to respond fast enough is a lesson for all. The digital age moves at a blistering pace, quickly turning winners into losers.

Successful companies across publishing, media, advertising, software and other industries feel this pressure today and continue to search for ways to respond. They seek to take advantage of digital business models and emerging technology and stay ahead of threat, turning it into an opportunity for future growth. The logic is impeccable. However, there is a problem. Borders made substantive investments in online book sales and digital book readers. Polaroid, the inventor of instant photography, brought the world’s first mega pixel camera to market in the 1990s.1 The Swiss watch industry previewed the world’s first quartz watch in 1969. Each of these firms went bankrupt because of innovations that they created or in which they had made investments.

The failure was not one of insight, but of execution. They moved too slowly to capture the opportunity and underestimated the scale of change required. The paradox of success is that while it should make incumbents best positioned to lead the market in the next wave of innovation, in reality it is the factor that most pins them to the past. Though these companies realize the market is moving and thus creating new opportunities, they do not successfully execute and capture the opportunity.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Our research focuses on these moments, when a business faces the paradox between transforming for the future and securing its current market position. It is unlike the turnaround crisis, which are the basis for most classical formulations of change management. Relatively speaking, this is straightforward. When a firm’s existence is at stake, all things become possible; however, when you are transforming from a position of relative strength, leading change requires a new toolkit; a toolkit that is capable of managing the tension between the past and the future and the barriers to effective execution that it creates. We conducted hundreds of qualitative interviews and a survey of more than 100 firms. We have built detailed profiles of firms facing this situation, defined the most common barriers firms face and isolated the key practices that contribute to success. Our conclusion is that this new toolkit needs to become core to everything a firm does; it cannot be a separate program or initiative.

The toolkit needs to confront the reality that core businesses in successful firms are often ‘tribes’ that defend the past, the sources of their revenue and expertise. It needs to be able to get beneath the sources of this resistance, to the root and issues that frustrate execution. And, it needs to help firms recreate strategic planning, leaving behind stiff formalities and embracing a rigorous, transparent approach to strategic decision-making. This paper outlines each of these points.

Warring Tribes

When Ben Verwaayen became Chief Executive at British Telecom in 2002, he found an organization gripped by tribal politics.2 The business had systematically ignored the implications of the internet for its residential customers and was refusing to invest in a substantial increase in availability of Broadband or DSL to the home. As a result, Britain was an international laggard in DSL, ranking next to Estonia for penetration of the consumer market. British Telecom had dedicated itself to a single agenda – telephony – at the expense of an emerging trend that threatened the status quo. BT’s twenty-five person ‘Management Committee’ held together the fragmented units, but effectively prevented initiatives that would accelerate progress on cross-business goals. Its approach to the broadband innovation typified this approach. The fragmentation of BT was such that it launched two under-funded competing products against itself in the emerging space. They had no overarching goal or corporate mandate. They openly competed for customers and took contradictory approaches to the market. The ‘Management Committee’ did not openly discuss the conflict these upstart units created; they relegated the innovation as a lower level management issue.

This is a familiar scenario in the successful firm and is at the heart of the strategic paradox. The more autonomous a line of business, the faster it can move – for example, BT formed two broadband initiatives with a high accountability for performance within each, but incompatible business goals. However, when the need to explore into new areas cuts across the established boundaries, then the antibodies resist and kill the innovation. CEOs or business unit leaders in this situation are often reluctant to take on the established businesses. This inaction enables ‘Warring Tribes’ to emerge; business units who defend their turf at the expense of broader organizational goals.

In 2006, SAP CEO Leo Apoktheker committed the firm to developing a software-as-a-service offering for smaller businesses available on a monthly subscription, with a no installation-required model. This was in stark contrast to the firm’s legacy of earning annual license fees from large enterprise software installations. Critically, the innovation crossed lines of business responsibilities. Apoktheker sought to avoid conflict by splitting responsibility between two functional heads. Coordination between units weakened and SAP could not make decisions quickly enough. Continual disputes about resources and responsibilities across the participating functions ensued without a clear mechanism or leadership for resolution. The Warring Tribes triumphed, the Board fired Apotheker and SAP missed a market that IDC estimates will account for 85% of all new software by 2012.3

Verwaayen and Apoktheker’s predicaments are familiar to many successful organizations. Some executives, and boards, defend boundaries between units with quasi-religious zeal. Verwaayen took on the resistance head-on. At a senior leadership conference, he marched from table to table with a microphone challenging individuals to say what they were doing to advance his goal for the business. “What are you doing to advance broadband? So tell me what you will do, something, anything.” Senior managers feared the public humiliation of not being able to answer.4

Align for execution, root and branch

Verwaayen made the paradox between old and new binary: “get on my agenda or face the consequences…” His success in broadband, though important, was relatively short-lived as parts of BT’s business imploded in 20085, causing the stock to tumble to all-time lows.6 Many of the leaders Verwaayen had threatened to embarrass were still in place as he exited. Verwaayen was successful in forcing BT to achieve its goals for broadband and shifted the business away from telephony. However, he did not alter the fundamental DNA of the business. He had not addressed the root causes of the original resistance to broadband that had driven the organization to resist its introduction. Broadband was a campaign, not a transformation.

In proactive transformations, where there is no crisis, it is critical to find the underlying source of resistance. One vivid example of this comes from the advertising industry. In the past 5 years, it has confronted the emergence of digital and online advertising channels such as Google, Facebook and iPad Aps. Television advertising is slowly losing ground to these new channels, now growing only in Asia. Print media spend is collapsing everywhere, with both being replaced by digital advertising growing at 16% per annum.7

Television advertising has been made in the same way for fifty years. Account executives take the client brief, Planners convert this into a creative brief that links the business requirement to what they know about consumers, Creatives come up with the bold imaginative concepts that production converts into television and media planning buys airtime to distribute. The agency earns its fees as a percentage of what the client spends on advertising. The client waits and watches its metrics for an uplift in sales in the targeted segments.

Digital advertising is different, it needs capabilities not found in the traditional agencies. Realizing that, large advertising agencies opened their doors to a new breed of digital marketers. They brought in new technical and creative skills in an effort to keep pace.

However, clients began to complain that their approach was simply to ‘add-on’ the digital components to a television campaign. The agencies lacked the capacity to deliver on an integrated marketing approach that used both in combination. Clients moved all or some of their work to smaller, more digitally savvy agencies, leaving the traditional players scrambling to respond. In our research with one large agency, we learned how they got to the root cause of this problem – that digital marketing threatened the core capability of the traditional advertising agency – creating television commercials. Interactive marketing is a software project. Building websites and iPhone applications requires production to be involved at the conception of a project, as software developers need to understand user requirements can begin before development. They also challenge the established boundaries between disciplines, bringing creative insight on how to use technology to the forefront of the process. Even more disruptive to the business model is that digital advertising works on a fee for service model: the ‘Mad Men’ days are truly over.

Advertisers have learned that new people cannot change how a business functions all on their own – people, process, capabilities and culture all need to be aligned. Transforming into new areas requires a deep understanding of the competence you are seeking to build – hiring experts to aid in this process will not, in itself, guarantee success. Successful organizations develop deep competency that is embedded in how work is done, who gets promoted, and how ideas are evaluated. The Swiss Watch industry struggled to understand the Quartz watch because it represented material science, not mechanical engineering. There is a need to pinpoint how the competencies required to take advantage of the new innovation that threatens the established way of doing things. Getting to the root of what it takes to execute a new strategy is critical for firms to navigate successfully the paradox between new and old; otherwise, the old will simply reassert itself, as it did at BT.

Ending the Kabuki-drama of strategy

Our contention is that at BT, in the advertising industry and in the many other companies we have referenced, there is a need for a new approach to strategy. For many companies, the annual strategy plan is more like Japanese kabuki drama; a set-piece performance, in which everyone knows the role they have to play. Bold plans describe intentions and aspirations, but shy away from the more challenging topic of how to execute.

This means that though strategy changes, execution does not. As a result, strategies go unexecuted and firms end up with the strategy they started with and were trying to change. When markets are stable, firms can afford some amount of failed execution. When the shift in strategy involves embracing new, disruptive opportunities, and the scale of change and risk are so much higher, then the failure can become terminal.

There is a profound contrast between Strategic Execution and this traditional strategic planning process. Its practices create a more transparent conversation where executives can confront the most challenging questions constructively and agree on what to do. IBM is one company that has made the mantra of ‘strategic execution’ core to its way of doing strategy for the past ten years.

In the early 1990’s, IBM was within weeks of bankruptcy, having failed to grasp the scale of transformation posed by the emergence of personal computing and the importance of Microsoft’s operating system software. A deeply entrenched global bureaucracy had thwarted efforts to change and taken the company to the brink. Saved from this near death experience, IBM re-emerged and by 2000, was an even stronger player with multi-billion dollar IT hardware, software and services businesses. Learning from its history it sought to transform again, but this time from a position of strength. Pursuing a new strategic insight that value was moving to integrated solutions that solved business problems; the company retooled its strategy planning process to make ‘strategic execution’ a primary focus. As Bruce Harreld, the head of strategy and marketing at IBM, has written: “strategy doesn’t matter unless it changes what the company does in the marketplace. Otherwise it’s ‘chartware.’”8

Harreld’s approach did not mandate a new way of working to the line of business general managers. He understood that he had to enable them to reach the conclusion that adapting to the strategy would mean shifting the people, processes, skills and behaviors of their organizations. He provided the tools, issued the invitation and they reached the conclusions. His approach included three important elements that other companies can replicate:

Build a common language – Harreld collaborated with Harvard Business School Professor Michael Tushman and his co-author from Stanford GSB Professor Charles O’Reilly to develop a framework for Strategic Execution. The Business Leadership Model (Figure 1) became a template for the IBM Annual strategy plan. It had the familiar components of strategic decision-making – vision, market insight, innovation trends and business design. However, aligned with it were questions about what needs to shift in the organization for the Business Leadership Model to execute effectively. This enabled Harreld to explore the topics of how talent, organization and culture impact the ability to achieve the chosen strategic direction.

Lead strategic dialogue – Harreld then invited general managers to apply this model in an open transparent conversation about what it would take to execute the strategy. These Strategic Leadership Forums were 3.5 day workshops that blended education from Tushman & O’Reilly with the application of the model to the strategy issues confronting their units. Over five years, IBM executives attended these sessions, in groups of up to 100, to work on tough issues and agree on how to advance different growth initiatives.

Adopt fact-based rigor – aligned to this open dialogue is discipline of examining key strategic decisions with fact-based analysis. The Strategic Leadership Forum helped create shared understanding and belief, and the fact-base supported this with fact-based decision-making.

Explore systematically – these mechanisms created the space to explore new market opportunities, outside the rigidities of the line of business structure. Unlike strategy development within core business – where the primary focus is on incremental improvements to existing products or services – exploratory business formulation involves a ‘test and learn’ approach. Explore businesses launch pilots and iterate value propositions in response to customer feedback. The management system used to monitor progress also needs to be adapted. Attention needs to be less on usual business outcomes, such as revenue and profit, but rather on achievement of key ‘lead indicators’ that tell executives whether the experiment is on track or not.

IBM’s exploratory businesses were called ‘Emerging Business Opportunities’; mini-business units to explore opportunities in ‘business value areas’. In many cases, these opportunities cut across organization lines, such as Life Sciences, Linux or Pervasive Computing. These units had a high-degree of autonomy over the people they hired, the culture they instilled and even the compensation approach. IBM gave them exemptions from some key business rules and processes when it was necessary to build units capable of executing on the specific business opportunities.

IBM’s approach enabled the lines of business to have an open conversation. Rather than a conversation about the ‘rights’ of lines of business, they engaged together and solved problems that benefited the corporation overall. These new businesses have since grown to an estimated $25B of revenue.10 Less tangibly, the approach enabled a shift in the way IBM’s executive population executed the strategy of creating a ‘business value.’ The practices of common language, strategic dialogues, fact-based rigor and systematic exploration allowed IBM to balance old and new in a way that has enabled both to flourish.

Planning for Paradox

The practices of Strategic Execution applied at IBM, and now at many other firms, offer a distinct set of mechanisms for balancing the old and the new. They encompass a process for systematically exploring new market opportunities and investigating the practical realities of executing them. Strategic Execution enables executives to engage ‘Warring Tribes’, rather than confronting them or allowing them to rule. Strategic Execution offers a language and discipline for investigation the execution barriers, which is fact-based and systemic. Strategic Execution creates a transparency that makes it possible to talk about ‘sacred cows’ that need to be taken on or challenged for a new strategy to be executed successfully.

Navigating the paradox between old and new is about holding open the possibility of both. Executing on today’s priorities to deliver revenue and supporting a high-degree of strategic diversity with many explore options. These practices of Strategic Execution keep the tension in the paradox alive and help firms to be nimble and agile; open to possibilities of what will emerge and, critically, able to capitalize on them when they do. Making the practices of Strategic Execution a core capability creates the opportunity to get ahead of the curve and lead the next wave of innovation in your market.

About the authors

Andy Binns(andrew@change-logic.com) is the Managing Principal of Change Logic, a consulting firm based in Boston, with offices in Palo Alto and London.

Wendy K. Smith (smithw@udel.edu) is Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior at the University of Delaware’s Alfred Lerner School of Business.

Notes

1.Tripsas, M. & Gavetti, G. 2000. Capabilities, Cognition and Inertia: Evidence from Digital Imaging. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (Summer Special Issues): 119-142 2

. Michael L.Tushman, David Kiron, Adam M. Kleinbaum, British Telecom: The Broadband Revolution, Harvard Business School, June 2006

3. Worldwide Software as a Service 2010–2014 Forecast: Software Will Never Be the Same, International Data Corporation, July 2010

4. Michael L.Tushman, David Kiron, Adam M. Kleinbaum, British Telecom: The Broadband Revolution, Harvard Business School, June 2006

5. BT warns of more losses after profits plunge by 81 per cent, The Independent, February 13, 2009

6. Indeed, the United Kingdom still ranks only 25th in the world in terms of average broadband connection speeds according to State of the Internet Q2 2011 Report, Akamai, 2011

7. Get Online, The Economist, January 4, 2011 8. Tushman, Harreld, O’Reilly, California Management Review, Vol. 49, No. 4 2007

9. Tushman, Harreld, O’Reilly, California Management Review, Vol. 49, No. 4 2007

10. Tushman, Harreld, O’Reilly, California Management Review, Vol. 49, No. 4 2007

[/ms-protect-content]