A new and powerful way to compete has taken shape in our business landscape: Platform competition

Whether we are talking about Google, Apple’s iPhone, iTunes and iPad, or Facebook, platforms seem to have taken our business landscape by storm. Firms that provide these platforms are able to orchestrate and take advantage of innovation coming from myriads of other firms that operate in coalitions sometimes called innovative business ecosystems. This article aims to present succinctly the essential ideas that managers need to understand about platforms, whether they are attempting to pursue a platform strategy or defending themselves against a platform attacker.

What are platforms?

Microsoft Windows operating system, Linux operating system, Intel microprocessors, Apple’s iPod, iPhone and iPad together with iTunes, Google the Internet search engine, the Internet itself, social networking sites such as Facebook, operating systems in cellular telephony, video games consoles, but also payment cards, fuel cell automotive technologies, and some genomic technologies are all industry platforms. Industry platforms are products, services or technologies that are developed by one or several firms, and serve as foundations upon which other firms can build complementary products, services or technologies. Building on these platforms, a large number of firms, loosely assembled in what are sometimes called innovative business ecosystems, develop complementary technologies, products, or services.

What is different about platform competition?

Platform competition is different from competition as we know it, because instead of firms competing directly with each other, there are coalitions of firms competing between each other. These coalitions comprise a loosely grouped range of firms that develop products, technologies or services that are complementary to the platform. They may not be part of the same company, nor even the same supply chain, but their destinies are linked together.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

The emergence of platforms is changing the ways firms innovate. Industry platforms tend to facilitate and increase the degree of innovation on complementary products and services. The more innovation there is on complements, the more value it creates for the platform and its users via so-called network effects, creating a cumulative advantage for existing platforms: as they grow, they become harder to dislodge by rivals or new entrants, as the growing number of complements acts like a barrier to entry. The power of an early installed base can therefore become a self-fulfilling prophecy, and many firms have attempted to grab as much installed base as possible by heavily subsidizing their product or even giving some basic version of it for free, such as with Adobe Reader.

Platforms at the core of innovative business ecosystems

Platforms provide an essential, or ‘core’, function to an encompassing system-of-use. They are subject to so-called network effects, which tend to reinforce in a cumulative manner early-gained advantages such as an installed base of users, or the existence of complementary products. Platforms must be core to a technological system of use (essential to its function) as well as highly interdependent with other parts of the technological system. The organization of these ecosystems seems to follow a regular structure, with platform leaders acting as keystone members of the network of firms that are the platforms’ complementors. There is a dense set of interdependencies, both technological and strategic, between the platform core and other parts of the business ecosystem and its associated technological system. The complementors themselves occupy a peripheral positioning within the network.

With over 680 million users worldwide and £1.2 billion revenue from advertising, Facebook has developed ways to entice other firms to link themselves to Facebook, adding value to Facebook users as well as allowing these complementors to access the value from the Facebook user base. According to the Financial Times, more than two million sites have integrated with Facebook since 2008, including 90 per cent of the top 1,000 sites on the internet. That number is growing by about 10,000 sites a day. Nearly one-third of Facebook’s users interact with it on third-party sites every month. In this way, a growing portion of online activity involves Facebook, even though it is not happening directly on Facebook.com1.

Platform leadership

In my own research on platforms which I have conducted over the past 12 years, often in collaboration with Michael Cusumano from MIT, I have focused on the strategic aspect of platforms, and developed the concept of platform leadership. Platform leaders are organizations that manage to successfully establish their product, service or technology, as an industry platform. As such, they reach a position that enables them to drive the technological trajectory of the overall technological and business system of which the platform is a core element, as well as derive an architectural advantage from their position in the industry. Industry platform leaders orchestrate firms that do not necessarily buy or sell from each other, but whose combined products, technologies or services add value to the ecosystem as well as to end-users. Platform leaders are highly dependent on innovations developed by the other firms, but, at the same time, take it upon themselves to ensure the overall long-term technical integrity of its evolving technology platform.

Platform leaders aim to create innovation in complementary products and services, which in turn increase the value of their own product or service. Simultaneously they wish to maintain or increase competition among complementors, thereby maintaining their bargaining power over complementors. Platform leadership is therefore always accompanied by some degree of architectural control. Furthermore, the momentum created by the network effects between the platform and its complementary products or services can often erect a barrier to entry from potential platform competitors.

Establishing an industry platform requires not only technical efforts from the platform leader to increase value creation opportunities for the ecosystem participants. It also requires the platform leader to attempt to establish a set of business relationships that are mutually beneficial for ecosystem participants. Therefore, an important idea that managers must remember is that technological design and business relationships are to be dealt with together when attempting to create or sustain a platform.

Has your product got platform potential?

Not all products, technologies or services can become platforms. There are two pre-conditions for a product, service, or technology to have ‘platform potential’: (1) Does it perform a function that is essential to a technological system? And (2) Does it solve a business problem for many firms in the industry? If you cannot answer positively to both questions, your product or service probably does not have platform potential. However if the answer is yes, then you can start the real work of not only building an ecosystem of complementors around your product, but also ensuring that your product remain attractive to a continuous flow of complementors by continually innovating your product. Keeping that momentum going will be essential to sustain the interest and the passion of your complementors. You also need to design business models that are convergent enough (that is, leave enough money on the table) to make it worth their while to develop complements to your platform and not your rivals’.

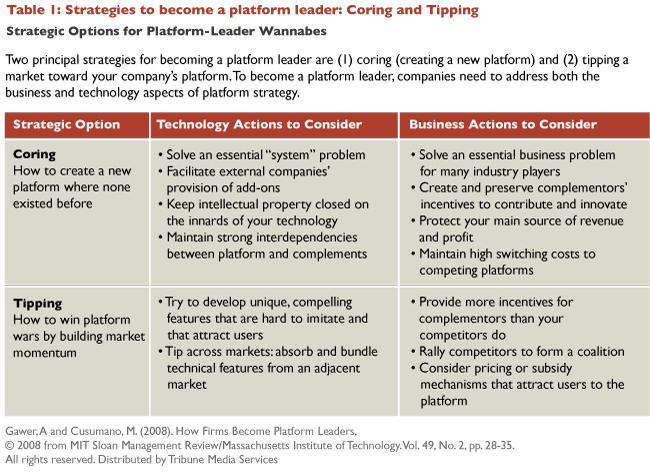

In a recent article coauthored with Michael Cusumano, we have identified two generic strategies, ‘coring’, and ‘tipping’ to win in platform battlegrounds. ‘Coring’ answers the question of how one establishes a platform where none existed before. ‘Tipping’ is the answer to how win in a platform competition. Table 1 summarizes what coring and tipping entail.

Coring is the set of activities or strategic moves a firm can use to create a platform when none existed before, by identifying or designing an element (that can be a technology, a product or a service) and making it fundamental, or ‘core’, to a technological system as well as to a market. Tipping is the set of activities or strategic moves firms can use to shape market dynamics and win platform wars when at least two platform candidates compete. These moves cover sales, marketing, pricing, product development, and coalition building. Note that for each strategy we recommend that both technology actions and corresponding business actions be undertaken. We found that a common mistake firms made was to focus either too much on the technology actions and not enough on the business actions, or vice versa.

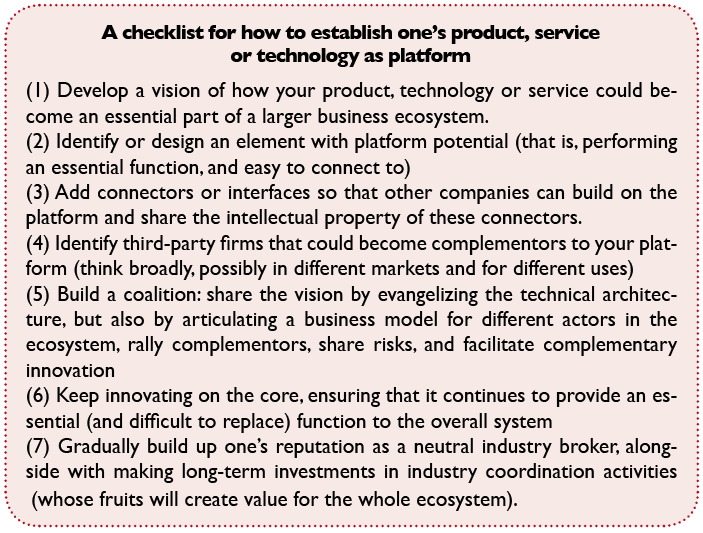

One of the important points of Table 1 is that choices about the design of the platform are intimately related to choices about structuring the business relationships among ecosystem members. To provide more detail on how firms can successfully create a new platform where none existed before, — in other words, perform a ‘coring’ strategy–, I suggest a 7-step process summarized as a checklist (See Box).

Particular dangers of platform competition: The Trojan Horse strategy

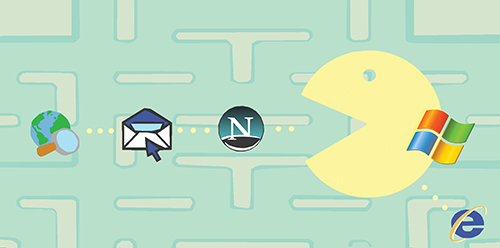

Platforms structure and facilitate inter-firm collaboration, but it is also important to understand that they change the way to compete. A particular danger of platform competition is that your complementor of yesterday could become a substitute and even dislodge you as a competing platform tomorrow. This so-called Trojan Horse strategy has often been used in digital platforms, perhaps facilitated by both the malleability of software code, and the technological ease with which one can absorb features and reconfigure software products.

Firms are quite savvy about this possibility: they are aware of it, whether as an offensive or a defensive move. For example, Netscape started as a complement to Windows, but Microsoft saw it later as a possible substitute and ‘gateway to the internet’ and fought it by absorbing similar features and bundling them as Internet Explorer. Similarly, Sun MicroSystems’ Java started off as a complement to Windows as well, only to later position itself as a layer that would make Windows substitutable to other Operating Systems. Google also started off as a complement to Explorer (as well as others) and gradually became a platform of its own. More recently, Facebook entered into the email market – starting as a complement to Outlook (using interoperability information disclosed by Microsoft) – but with the intention of offering a ‘filter’ that works inside Outlook (selecting mail from ‘Friends’ that would appear on top of the list) – demonstrating an avowed objective to transform Facebook into a platform on top of which other applications will run.

Concluding remarks

Managers aiming to achieve platform leadership fundamentally need to re-interpret their own product, service or technology, to situate them within a larger context, where they need to stimulate and orchestrate external innovation in a collaborative manner, while still operating within competitive environments. To create and sustain these innovative coalitions, platform leader wannabes can usefully apply the principles outlined in this article. As a last word, let us highlight that successful platform leaders need to pay attention to the reputation they acquire within their ecosystems, as their legitimacy as platform leaders rests on not only their technological superiority, but on their credibility as neutral brokers who genuinely care about the vibrancy of the ecosystem.

About the author

Annabelle Gawer is Assistant Professor of Strategy and Innovation at Imperial College Business School. She is an internationally-recognized expert and a thought leader in high-tech strategy. A pioneer in research on platforms, she has written two books and numerous articles on the topic. Her work has been published in the Wall Street Journal, the MIT Sloan Management Review, the Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, and Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Her work has been translated in Japanese and Chinese. She is a consultant to many large companies, including Microsoft, Nokia, Philips, Symbian, and Gemalto.

References

• Gawer, A. (2009) (Ed.) Platforms, Markets and Innovation. Edward Elgar.

• Gawer, A and M Cusumano (2008): How firms become platform leaders, MIT Sloan Management Review, 2008. Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 28-35

• Gawer, A and M Cusumano (2002): Platform Leadership: How Intel, Microsoft and Cisco Drive Industry Innovation. Harvard Business Press.

Notes

1. Financial Times. ‘Facebook’s grand plan for the future’. David Gelles. 3 December 2010.

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/57933bb8-fcd9-11df-ae2d-00144feab49a.html#axzz1PMQq8Z1m

[/ms-protect-content]

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)