By Shlomo Ben-Hur & Nik Kinley

Corporate Learning functions are under pressure to deliver like never before. Yet studies have repeatedly shown that business leaders’ satisfaction with the work of their learning functions has remained as low as 20% for the past decade. For an industry worth over $200 billion per year globally, that is a bad return on investment. In this article the authors lay out five critical changes to the way corporate learning is approached, that businesses need do to put things right and make corporate learning work.

Last year, a survey found that more than half of managers believe that employee performance would not change if their company’s learning function were eliminated.1 Some people exclaim a slight derisive laugh on reading this: it seems to play into their stereotypes about corporate learning. So they smile. Right up to the moment they remember how much learning costs. Then they stop smiling, because it often costs a lot. Globally, figures suggest over $200 billion is spent on corporate learning each year and it seems that the general feeling is that over $100 billion of that may well be wasted. Alarmingly, this wastage figure may well be on the conservative side. Because over the past ten years survey after survey has repeatedly shown that the proportion of business leaders who are satisfied with their learning function’s performance is around 20 percent.2 The stark reality is that by and large corporate learning is just not working as it should, and has not been for some time. And that is a lot of wasted money. In this article, we explain what needs to change: what businesses need to do to turn things around and finally make learning work.

This not a new issue, but it is one that cannot be ignored any longer. Fuelled by downturn-driven budgetary pressures and apprehension about the efficacy of learning interventions, demand for evidence of the impact and value of learning is growing fast.3 So a lack of progress in improving the impact of learning is suddenly meeting both heightened and hardened expectations. If corporate learning is to retain what remains of its credibility, something needs to change and it needs to change fast.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Of course, for anything to change, there needs to be some recognition that there is a problem. This may sound obvious, but we fear that not everyone is convinced of the need for change. For example, whenever learning leaders have been asked by surveys over the past few years what their biggest challenge is, they have persistently reported that their number one issue is demonstrating the value of their work.4 There is no doubt that demonstrating the value of corporate learning is a challenge. But we are surprised that it comes out as the number one concern. Our fear is that this finding reveals an assumption that lurks in the background of corporate learning – the idea that there is nothing wrong with what is being done at present, that value is already being added, and that the poor satisfaction ratings are somehow not a fair reflection of what is being achieved. It is as if the issues are skin-deep, challenges of presentation and political positioning more than the substance of how learning works.

We could not disagree more. We are certain that the learning profession can, and often does, add value. We have seen and been involved in pieces of work that have made a genuine difference to organisations. Yet we also believe that the poor standing of corporate learning is not just about presentation, that it runs deeper than that. Top to toe, something is wrong and it is going to take more than a change in how learning is presented and positioned to put things right. With satisfaction levels hovering around 20 per cent, merely doubling or trebling them will not be sufficient. We need to quadruple them, improve them by a staggering 400 per cent, before we can start saying that corporate learning is in a good place.

Moreover, not only do businesses need to improve how they do learning, but whatever they do needs to be different from and better than what has been tried up to now. Because the apparent lack of progress in improving the standing of corporate learning comes despite significant amounts of effort and activity. In fact, the past ten years have witnessed big changes in the practice of corporate learning and the journals are full of case studies of genuinely fascinating, innovative and apparently excellent practice. It is not that things have not been happening or changing, but that the changes have either not been the right ones or have not been enough.

So what has gone wrong and what do businesses need to start doing? We have spent the past few years exploring this very issue and in our upcoming book The Business of Corporate Learning: Insights from Practice, we describe in detail what the major challenges and opportunities are. From all our research though, five key priorities stand out – five critical things that businesses absolutely must do to put things right and make learning work.

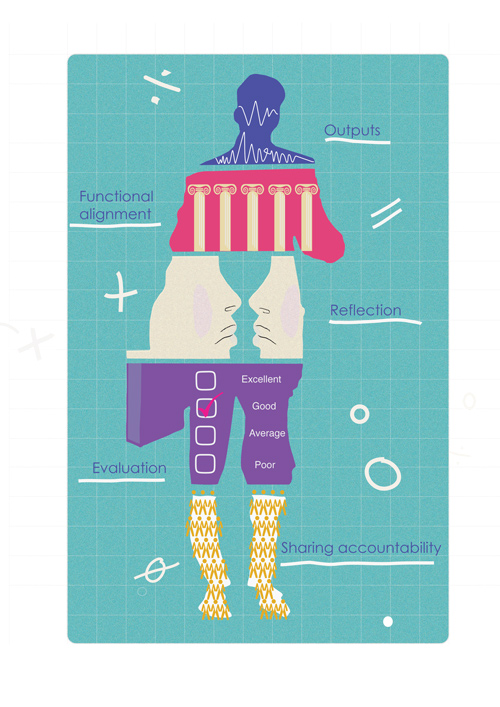

Focus on behaviour change, not learning

The first priority is a big, hairy, fundamental one and focuses on the overarching question of ‘What is corporate learning?’ This may sound dull and theoretical, but it has massive practical implications.

For the most part, at present people tend to talk and think about corporate learning in the same terms as they talk about traditional, academic learning. It is assumed to be about the accumulation of knowledge or the acquisition of skills. Something is given or passed on to the learner and the focus is on what is given and the process of how it is passed on. Yet viewing learning this way misses the point that it is not skills or knowledge per se that provides value to organisations, but how they are applied. To use a stereotype: academic learning is primarily focused on inputs, what is taught and what is learned; but corporate learning should be primarily interested in outputs, how the things we learn are used, and how they can be of value to individuals and organisations.

This does not mean that there is no place for traditional academic learning in organisations, especially when it comes to technical training. And we are aware that in some European countries companies have a legal obligation to provide training and continuing education for their employees and that this may sometimes resemble education in the traditional academic sense. But there needs to be a fundamental shift to recognise that, in the majority of organisations, much of corporate learning is not about traditional learning, but about changing people’s behaviour in ways that produce value for the business. And in this respect, the very word ‘learning’ misrepresents what organisations are trying to achieve.

The practical importance of this is that behaviour change is at present surprisingly absent from discussions of best practice in corporate learning. And perhaps this accounts for why many learning leaders apparently do not as we do – count developing and delivering effective corporate learning solutions as their number one challenge: because helping people acquire new knowledge and skills is, we would argue, a far simpler task than changing people’s behaviour in ways that improve their performance.

The rising application of behavioural reinforcement techniques such as gameification give cause for hope, as does the increasing influence of disciplines that are more overtly focused on changing behaviour, such as behavioural economics. So there is some change afoot, but it is too little and too slow. Once and for all, corporate learning needs to shake off the shackles of its past and recognise that it is fundamentally different from academic learning, and thereby free itself to face up to the real challenge before it.

Focus on functional alignment

The second priority focus is on how corporate learning teams are set up to deliver. Much of the thinking about corporate learning during the past decade has been about how it needs to be strategically aligned with a company’s business objectives. And this is undoubtedly important and critical to the success of corporate learning. But in order to translate such strategic alignment into operational results, learning functions also need to focus on how their internal systems, processes and people are functionally aligned both with their objectives and with one another. In other words, are the structure of the function, the mindset and capabilities of the people within it, and the design of learning systems, products and services all aligned with and capable of fulfilling the purpose of learning in the business?

This may sound blatantly obvious, and it is. But in our experience it is also too often assumed or overlooked and not explicitly considered. For example, a key question every learning function needs to be able to answer is, ‘How do we create value for the organisation?’ Of course, ultimately, all learning functions are in the same business, that of helping organisations to make money through performance support and improvement. But there is, as the old adage goes, more than one way to skin a cat. And how you envisage the role of corporate learning in creating value in the organisation can have significant implications for how it should be structured and organised.

For example, if a learning function needs to deliver hundreds of technical training programmes, then their operational model will need to be like that of a manufacturing or retail business. The function is likely to resemble a training factory that will focus on ensuring quality at volume, making efficiencies and delivering economies of scale. Conversely, if it is mainly focused on organisational development and the facilitation of change, then it will need to be operating more like an internal consulting unit. And if neither is the case and its focus is on the delivery of executive development, then its operating model will probably have a lot of similarities with that of a business school.

These are fundamental questions and our concern is that in too many businesses, the scramble to align learning with business strategy has led to the internal, functional alignment of the various elements that constitute learning functions being overlooked. This has to change.

Step in and out of the business

The third priority is to optimise the relationship between learning teams and their customers in the business. The late psychologist Bruno Bettleheim once allegedly said that the challenge in changing another’s behaviour is not so much being able to step inside the client’s head, to understand their motivations and thinking, as being able to step out again in order to think objectively about what needs to happen. In our view, this is exactly the issue now facing corporate learning. With all the focus on aligning with business needs, demonstrating value to the business, and developing organisational capabilities, there is the risk that learning functions can step in too far and lose their ability to be objective about what needs to happen. And if they are to achieve and retain credibility, they need to be able to contribute an objective viewpoint.

Part of the challenge here is a legacy issue, common to many of the HR and learning functions we have seen: namely, self-consciousness about how they are viewed and a strong desire to be seen in a positive light. There is nothing unusual about wanting to be perceived positively, of course, but it becomes a potentially negative issue when it is a key driver rather than merely a consideration, since it can constrain the ability to act. The recent research showing that learning leaders’ primary concern is demonstrating their worth to the business may well reflect current budgetary constraints and learning’s generally poor standing in business leaders’ eyes, but it may also reflect some of this self-consciousness.

Whatever the underlying issues, if learning functions are to add value they have to find a way to balance the need to be an integral part of the business with an equally strong ability to step outside it and take an objective view. They must apply, without bias, their expertise in learning science and behaviour change to the task at hand.

Apply market forces

Corporate learning is effectively a market with competing products and services, and if we want quality, efficacy and efficiency to prevail, we need to apply market forces. By this we mean that businesses need to be able to compare products and know what works and what doesn’t, so that they can make informed judgements about what they want to do, what they can do and what they need to do. And to do this, they need to focus on our fourth priority – getting evaluation right.

And herein lies a problem because corporate learning has spent much of the past forty years acknowledging this issue and discussing how best to address it, but without actually making any great headway. Faulty and incomplete models, limited resources and lack of expertise have all been cited as culprits. And there is little doubt that each of these has played its part. Yet after forty years of inertia, we cannot help but wonder if there is a lack of will in play, too – a general lack of desire to evaluate. After all, almost everyone has something to lose from rigorous evaluation, and it is in very few stakeholders’ interests to find out – or, even worse, admit – that a learning programme has not been successful. And we cannot believe that this dynamic has not affected learning functions’ eagerness to properly evaluate the impact of their work.

Of course, it is not only learning functions that are at fault here: one can hardly blame their reluctance, occurring as it does in the current context of failure not being tolerated or at least not forgotten. So any improvement in current evaluation practice is unlikely to happen until businesses understand that learning is a complex and difficult systemic task that usually does not work perfectly at first attempt, and needs to be evaluated and honed over a period of time. This message may not be easy to hear in many business environments, but it must be heard, because without proper evaluation we cannot apply market forces, and without this we cannot make informed decisions. And without that, corporate learning risks descending into mediocrity (or indeed, depending upon your viewpoint, remaining there).

Share accountability for learning

Research into corporate learning has persistently thrown up a critical, but often unrecognised finding: namely, that contextual factors such as the workplace environment are actually more important in ensuring the application of learning than the quality of the learning event. This is pretty staggering when you think about it.

Many businesses would say that they fully understand and appreciate this fact. But we are unconvinced. In a recent survey, 71 percent of respondents stated that their organisation expects managerial support as part of the learning process. However, when asked what managers are expected to actually do, 63 percent stated that they are only required to formally endorse the programme, and only 23 percent reported that managers have to physically do something, such as hold pre- and post-training discussions. Saying ‘I support you’ while doing nothing to back it up is not support, and businesses need to start accepting and understanding this.

Our fifth and final priority, then, is that the responsibility for ensuring that learning happens, behaviour changes and that performance is indeed improved needs to be shared amongst all the parties involved. If they want learning to work, businesses must not and simply cannot assume or implicitly reinforce the idea that corporate learning is only about learning teams ‘doing something’ to employees.

We believe that these five priorities are at the heart of what corporate learning needs to do to make learning work. And when we present these ideas to learning leaders, generally speaking, they do not disagree. The jump from learning to behaviour change is bigger for some than for others, but as yet there have been no gasps of disbelief or outraged cries of denial. Indeed, what seems to concern them most is not the ideas themselves, but how to implement them. On the last two points, in particular, we have heard the occasional sharp intake of breath or long sigh, at the thought of strong impact evaluation or creating greater visibility around the business’s role in the learning process.

But businesses and learning leaders do need to act and act soon. Indeed, the change is needed now more than ever because the development and deployment of learning solutions has become more challenging by the year. Organisations are increasingly expecting more for their learning money: moving to more cost-effective solutions, demanding faster design and delivery cycles and more accessible content. All of which places pressure on learning solutions by creating greater need for compromise in their development and deployment.

So we have a crisis, and a big one at that. But it is not all doom and gloom. Indeed, we have great hope, because as skill shortages and decreasing opportunities to achieve competitive advantage drive businesses to look internally, learning leaders have the attention of their organisations like never before. They may be under greater pressure to deliver, but they also have the stage and the opportunity to put things right.

About the Authors

Shlomo Ben-Hur is an organizational psychologist and professor of leadership and organizational behaviour at the IMD business school in Switzerland. He has more than 20 years of corporate experience in senior executive positions including vice president of leadership development and learning for the BP Group, and chief learning officer for DaimlerChrysler Services. His new book The Business of Corporate Learning: Insights from Practice, will be published in March 2013.

Nik Kinley is a London-based independent consultant who has specialized in the fields of behaviour change and talent measurement for over twenty years. In that time he has worked with CEOs, life-sentence prisoners, government officials, and children. His prior roles include global head of assessment for the BP Group, and head of learning for Barclays GRBF. His new book Talent Intelligence, written with Shlomo Ben-Hur, will be published in June 2013.

References

1. Corporate Leadership Council. (2012). Driving the Business Impact of L&D Staff. London: The Corporate Executive Board Company.

2. Accenture. (2004). The Rise of the High-Performance Learning Organization. Results from the Accenture 2004 Survey of Learning Executives. London: Accenture.

3. Giangreco, A., Carugati, A., & Sebastiano, A. (2010). Are We Doing the Right Thing? Food for Thought on Training Evaluation and Its Context. Personnel Review, 39(2), 162-177.

4. Accenture. (2004). The Rise of the High-Performance Learning Organization. Results from the Accenture 2004 Survey of Learning Executives. London: Accenture.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)