By Adrian Done, Chris Voss and Niels Gorm Rytter

Several key factors influence the short-term success and long-term sustainability of best practice interventions. Management of these factors is critical to instilling a culture of capability development – especially within small and medium enterprises.

In the fight against challenging economic conditions, many businesses and organizations are asking themselves how they can “do more with less” by implementing best practices such as Lean (just-in-time) or Six Sigma (total quality management) or similar continuous improvement management methods. Few have greater need to make such profound changes than the legions of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) that constitute over half of the jobs in developed countries. In the USA, fewer than 12% of firms have more than 20 employees, yet it is the smaller companies that comprise the majority of US firms that have the most limited resources to initiate and drive operational performance improvements. While those SMEs that are members of sophisticated supply chains might gain significant help from large OEM customers, the rest have to find other ways of driving improvements through introducing new ways of working and new innovative practices. To this end, many SMEs turn to best practice interventions (BPIs) as a cost-effective means of improvement. Their hope is that such short focussed programmes lead to both short-term success and long-term sustainability of best practices through instilling a culture of continuing capability development. Yet our research indicates that this is a danger ous assumption and that several underlying issues need to be understood and managed for BPIs to be considered truly effective capability building processes. We find several barriers hindering BPI outcomes in SME contexts – both in the short and longer-term, and discuss guidelines that companies should pursue to focus attention upon sustainable outcomes.

BPIs typically have both short- and long-term objectives. Short-term objectives are aimed at performance improvements and long-term objectives usually seek to embed best practices across the organization. Larger organizations are more likely to possess the resources to implement practice improvements and thus publicly funded intervention programs have been created specifically to offer SMEs support in learning about and adopting best practices.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]There are two important issues with such BPIs. First, there is an underlying question as to whether a short one-off intervention can lead to sustained change in the organization’s practices and, hence, long-term performance. Second, there is an implied interplay and potential conflict between short- and long-term objectives as trade-offs, diminishing returns and diminishing synergies that impact the way a company may improve towards its production frontier. Over-emphasis on short-term objectives may lead to the neglect of long-term ones. On the other hand, successful short-term outcomes may be a major contribution to the visibility and acceptance of new practices in the long term. Introducing new ways of working and new innovative practices is generally a difficult process.Short-term benefits must be created but it is still mostly a long-term journey. How should companies handle this dilemma?

Best Practice Interventions (BPIs)

A BPI can be defined as an activity designed to introduce new practices through a series of short focused activities in the organization. These interventions are typically composed of two parts. The first part aims for dramatic improvements within a focused operational area in a very short time. The second part focuses on the introduction of new (often seen as either “best” or promising) practices or processes and on preparing the organization for the ‘journey’ required for widespread adoption of these practices by transferring and building skills through action learning and applying lessons learned in practice. BPIs typically consist of preparation activities, one or more improvement workshops (usually less than a week), finishing events and follow-up activities. The practical delivery of these activities depends much on the skills, competencies and behavior of the consultants or change agents leading them. These interventions can cover a wide range of practices in areas such as TQM/Six Sigma, just-in-time (JIT)/lean production, and total productive maintenance (TPM). The interventions can be part of a supplier development program (where an OEM is seeking to transfer best practices to its suppliers), part of a governmental support program or part of the services of consulting organizations. Those involved in BPIs must deal not only with the demands and distractions from daily operations but also with other improvement projects claiming attention and resources.

Whilst different BPIs (TQM, JIT, TPM etc.) consist of unique and common practice elements, one thing they share in common is that they are directed towards improved performance. The desired performance outcomes of BPIs are in two areas. Firstly, they can be expected to influence operational performance in areas such as cost, quality, flexibility, lead times, inventory, transport, delivery time and delivery dependability in the short term. These, in turn, can potentially lead to improved financial performance. The second desired impact is concerned with the long-term embedding of the practices. If the interventions are to make the desired impact then achieved improvements in both practice and performance must be sustained, must spread to the whole organization and must lead to further or future improvement in other areas. However, embedding and sustaining new practices is not easily achieved. BPI programs often focus on the “low hanging fruit”, resulting in quick short-term gains but also in problems with sustaining any improvements. It is not uncommon for improvements to be transient and practices to be dropped after initial enthusiasm. Furthermore, sustainability is fragile and decay of original gains is common. Maintaining momentum, once low hanging fruit has been harvested, is an important issue and something that Japanese companies have been observed to do well. In one study only two out of the five organizations had persisted with their quality programs five to ten years later despite initial effort and short-term benefits. Furthermore, in their enthusiasm for the BPI process itself organizations can fail to see the deeper more fundamental changes that are needed for real sustained process improvement to be realized. Thus, integration of immediate success with long-term objectives is critical.

There is thus a dilemma facing many organizations that seek to introduce new and promising practices or those that seek to help others to do so. It has been widely argued that this process of integrating immediate successes with long-term objectives requires longer programs of change to introduce new practices effectively. However, many organizations find it difficult to fund or resource long-term support. For example, unlike larger organizations, SMEs typically have little in-house expertise and can less afford the cost of long-term support. Government and professional bodies that promote such programs of change also find it difficult to fund long-term support. The result has been a tendency towards development and implementation of short programs or interventions designed both to make a quick impact and to develop the base from which new practices can be adopted in the long term. This leads to the following question:

What factors drive short-term success of BPIs and long-term sustainability of best practices?

Our research has found three sets of factors that potentially contribute to (or inhibit) short-term improvement and long-term sustainability. The first set of factors relates to the company context within which the intervention occurs. The second broad set of factors is associated with the design and implementation of the BPI itself. The final set of factors relates to the approach of the change agent or consultant. Within each of these sets, there are several underlying factors inherent in management approaches and which have performance and sustainability implications. These are:

1. The Intervention context

• Clearly communicated strategy and objectives for change: A clear corporate operations strategy outlining objectives and the role of best practices in developing competitive advantage for the company, as well as communicating it to all corners of the organization are keys to successful BPIs and organizational change.

• Organizational readiness for change: Operational change programs will be more effective if the organization is prepared for and committed to future changes – with a dominant coalition of stakeholders that are (or become) open towards and commit to future changes.

• Key performance indicators (KPIs) aligned to the program of change objectives: A key leadership task is developing a culture oriented towards performance. Such performance cultures are based upon the implementation, capture and analysis of appropriate performance measures in order to drive behavior and commitment towards different assignments.

• Reward and recognition of positive short-term results: When short programs, such as BPIs, are used as a basis for long-term change then reward and recognition of positive results achieved in the early phases may help motivate stakeholders to be committed to longer-term transformation.

2. The Intervention design and implementation

• Tailoring the BPI format to the specific context: The careful consideration of aims and scope alongside thorough process planning and content preparation is a key success factor for organizational change and BPI projects.

• Organization and provision of intervention resources: BPIs typically compete with ongoing daily operations and other parallel projects for stakeholder attention and limited resources. Yet, unless the BPI is well organized and given sufficient priority over other activities, with adequate provision of resources, it is likely to suffer in terms of its short and long-term impact.

• Intervention implementation: BPIs can be of variable duration and programming: the timing, sequencing and pacing of such events can contribute to whether change is welcomed and sustained. Thus care should be exercised in formulating an appropriate implementation process.

• Stakeholder management: Paying due attention to the needs of different stakeholder groups (senior management, middle management, employees, team members and members of other impacted functions), as well as the management of their expectations is an important aspect of managing BPIs.

• Developing internal facilitators and change “champions”: A charismatic and driven leader can coach people and build confidence, commitment and motivation – all of which are critical to the short- and long-term success of a BPI.

3. The Change-agent’s approach

• Change-agent’s overall knowledge and competence: The outcomes of BPIs depend much on the skills, competencies and behavior of consultants, facilitators or change agents leading them.

• Plan for ongoing activities and consultant support: The process of adopting best practices is a long journey that will most likely go well beyond the duration of a short-term BPI project. Thus planning for ongoing activities with the BPI consultant can be beneficial.

The Outcomes of Best Practice Interventions

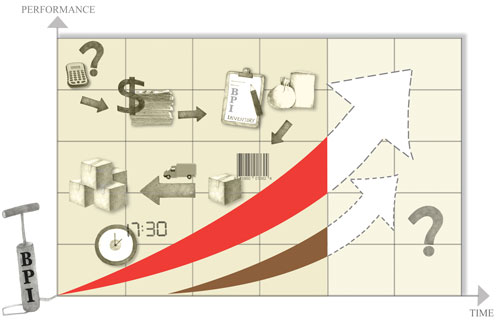

In our research we observed seven BPI short- and long-term outcome trajectories. Figure 1 shows how outcomes changed over time, on a simple five-point scale of performance and practice improvement compared to the pre-intervention level 0: 1- Bad (Little improvement);

2- Unsatisfactory (Limited improvement);

3- Satisfactory (Average improvement);

4- Good (Above average improvement);

5- Excellent (Significant improvement & deployment).

We found that all interventions delivered at least some short-term improvements immediately after the BPI, though the degree of improvement varies considerably from very little improvement to satisfactory short-term performance outcomes. In the long term, however, the variability in outcomes was even greater. Only a minority of cases achieved the A-trajectory of excellent improvement- whereby solid short- and medium-term improvements were sustained and additional further significant gains were made and rolled-out to other parts of the organization.

Even those that were successful in the short- and medium-term could stall in the longer term and fail to continue with best practice roll-outs (Trajectory B). More common are the low to moderate successes that are made in the short-term but with little or no further best practice improvements being carried into the long-term (Trajectories C, D and E). Of course, poorly implemented BPIs result in very little short, medium or long-term benefit (Trajectory G). But perhaps of most concern is Trajectory F- whereby any limited gains that were made in the short-term were lost as the organization fell back almost to pre-BPI levels with few of the best practices being sustained.

That a well-designed intervention will deliver some short-term success is to be expected, yet since a key objective of BPIs is to build a base and capabilities for wider change in the organization, the more important outcomes are in the long term.

Matching Outcome Trajectories with Underlying BPI Factors

Our findings are summarized in Table 1 and indicate that those companies that effectively manage and implement the majority of the eleven underlying BPI factors are the ones that have greatest short-term success and long-term sustainability of best practices. The best performing cases were those that account for all of the intervention context, intervention implementation and change agent approach factors. Conversely, those that did not effectively manage any of these dimensions were the worst short- and long-term performers.

Long-term outcomes

Most BPIs led to some improvement in the short-term, but few progressed to longer-term sustainability of the practices and performance. A key differentiating factor for those who progressed beyond the short term was the presence of a clear pre-BPI strategy for long-term change. Factors such as organizational readiness for change were associated with short-term success and were a necessary, but not sufficient condition for long-term success. Post-BPI reward and recognition were also found to be determinants in moving towards long-term success. Clear KPIs and a performance-oriented culture were drivers that marked Trajectory A from the rest. Those cases that planned and prepared for the subsequent deployment across the organization were most successful in the long term. The emergence of change champions was also found to be a critical driver of long-term success, indicating a need to develop grassroots’ “capacity-building leaders” to continue driving positive change. Despite the intention of BPIs to build capabilities for the organization to continue making positive changes without external support, we found limited evidence for SMEs that were capable of attaining sustained long-term success without such support.

Best practices such as lean production or six sigma methods are bundles of individual practices. Our data supports the view that partial implementation neither leads to short-term success nor provides a base for long-term development and diffusion across the organization. A BPI can only be considered successful if it meets both short- and long-term objectives. Yet our research indicates that only one in eight cases could be considered truly successful against criteria and only a minority made improvements to satisfactory or good outcomes in the long term. This raises the question as to whether BPI interventions are inherently flawed with a low chance of long-term success?

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Our data raises some serious questions about the general efficacy of BPIs in terms of moving beyond short-term success. At first sight it would seem that this was due to the failure to implement identified drivers of BPI outcomes. However, most of the organizations studied were small, had limited resources and had almost no prior capabilities. In this context, how realistic is it to expect a single BPI, unsupported in the long term, to build sufficient capability for the organization to drive continued positive change? Furthermore, the dual short- and long-term aims of BPIs create a potential dilemma in SMEs: the interventions must deliver convincing short-term outcomes; yet also provide effective training to managers and personnel with a firm basis for long-term sustainable business change.

We conclude that BPIs should be seen primarily as capability building processes and their progress should be measured in terms of the achievement, deployment and sustainability of these capabilities. This contrasts with the more traditional view that BPIs are about implementation of a set of practices. Second, we conclude that the previously identified intervention context, design and implementation, and change agent approach factors can significantly contribute to the success of capability building. Third, there is an inherent tension between the lack of resources in typical SME users of BPIs and the short time available to develop a critical mass of capability. Our findings indicate that such BPIs are unlikely to develop sufficient capability for long-term success in SMEs without ongoing support.

This research has important implications for those funding, designing, participating in or delivering such programs. By their nature, BPIs are frequently aimed at organizations with limited capability and resources. Although they can lead to visible short-term improvement this is not enough. Rather than usually being seen as short-term exercises narrowly focussed upon localized implementation of “best practices”, the true objective of BPI programs should be aimed towards long-term building and deployment of capabilities across the organization. Therefore, leaders and managers should be aware of the drivers of successful outcomes that we had identified, many of which should take place prior to the BPI. Such implications also potentially apply beyond SMEs to the full range of organizations using BPIs.

The combination of a lack of initial capability, often difficult contexts, limited time and limited resources makes long-term BPI success very difficult to achieve in SMEs. Our research found only one of eight cases truly managed to make best practices stick: an SME managing to sustain the continued development and deployment of capabilities needed for long-term positive change is the exception rather than the rule. This gap has to be addressed by both funders and users of BPIs!

This article is based upon the article “Best Practice interventions: Short-term impact and long-term outcomes” in the Journal of Operations Management, 29 (2011) p. 500-513. The research was funded by the ESRC, grant RES-331-25-0027, through the Advanced Institute of Management Research.

About the authors

Adrian Done is an Associate Professor at IESE Business School and Research Associate with the Advanced Institute of Management Research (AIM). Prior to obtaining a PhD from London Business School, he spent much of the 1980s and 90s in international roles within the automotive industry- rising from project engineer to plant manager and gaining Chartered Engineer status en route. Adrian’s recent research, published across academic and practitioner communities, has received various awards from prestigious institutions. He is regularly invited to present at international conferences and to collaborate with organizations across various sectors.

Chris Voss is Emeritus Professor of Operations and Technology Management at London Business School, where he has served as deputy dean, and senior fellow at the Advanced Institute of Management Research (AIM). He is former president of the European Operations Managament Association. He has conducted extensive research into the areas of manufacturing strategy, best practices and improvement. His reports on Made in Britain and Made in Europe studies have been influential both for practitioners and government.

Niels Gorm Malý Rytter, Msc, PhD is Associate Professor at Aalborg University, Copenhagen Campus and affiliated with Copenhagen Business School, the Blue MBA (Shipping and Logistics) as lecturer, coach and examiner. Previously he was a guest researcher at London Business School. He has worked and was a board member in a family owned manufacturing company, and spent some years in container shipping industry. Today he does advisory services and is a frequent presenter for industry. His work focus spans over manufacturing to transportation, logistics and service industries – and his expertise is within Lean-Six Sigma, Operations and Service Management and Supply Chain Management.

[/ms-protect-content]

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)