By Matthias Holweg, Kai Hoberg, Frits K. Pil, Jakob Heinen

Companies struggle to define the value proposition 3D printing brings: While the opportunities for improving products are obvious, how to generate value from it is not. Firms need to first examine its potential and risks along three dimensions: product innovation, customisation, and complexity. Then they need to set clear boundaries for permissible customisation, and decide where to situate 3D printing within their organisation.

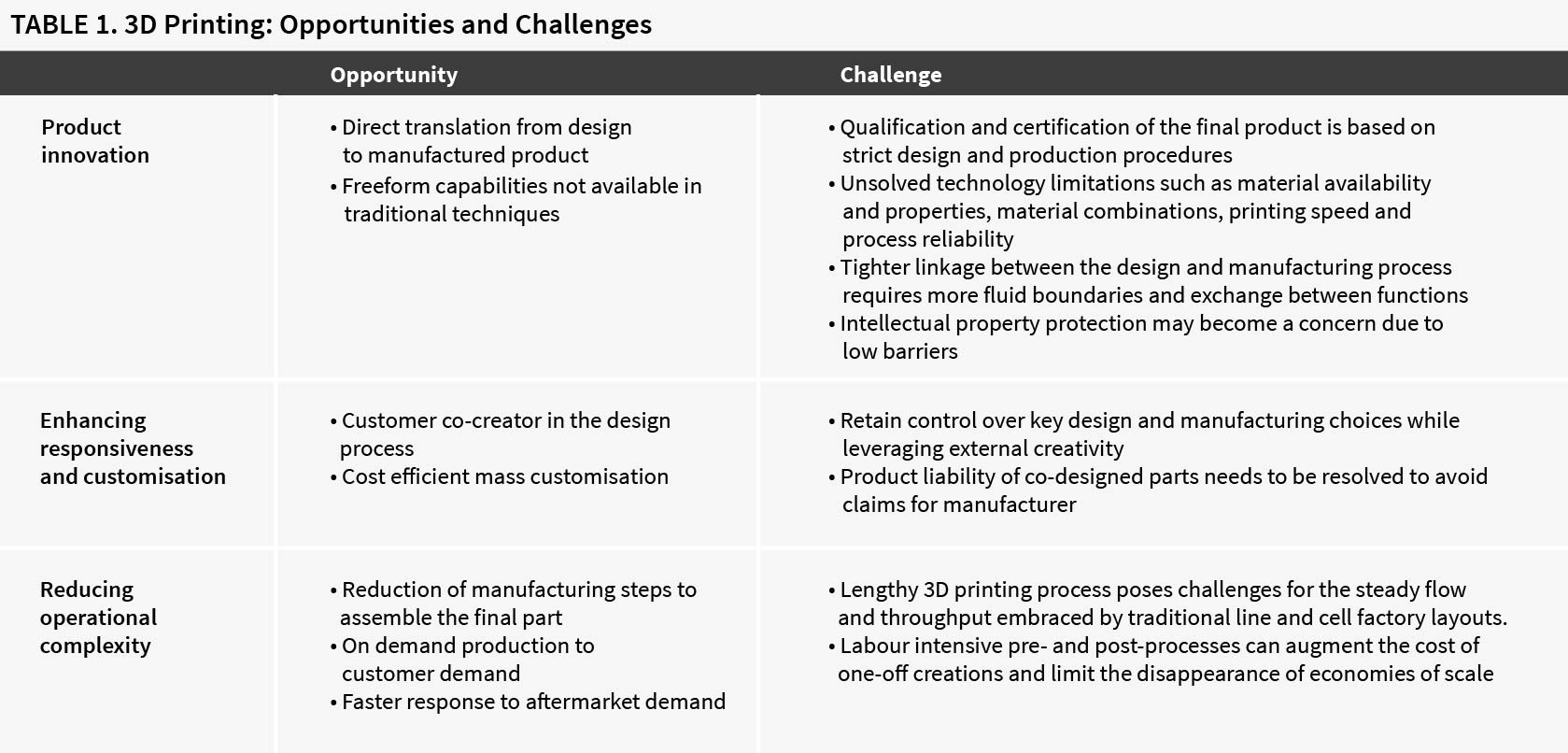

3D Printing: Opportunities and Challenges

Rapid prototyping technology, the ancestor to 3D printing,1 has been around for over two decades. One might rightfully ask whether there is any substance to the recent hype around this class of manufacturing technology.2 The answer is: Yes. We have reached a critical inflection point for 3D printing, and digital manufacturing more generally: The expiration of key patents (first for fused deposition modelling, and more recently selective laser sintering), has allowed a number of new entrants on the equipment side of the 3D printing services sector, substantially increasing the level of competition and associated innovation. On-going reductions in cost for key inputs have further driven down the investment needed to incorporate 3D printing into a firm’s repertoire of activities. These reductions are enabled by lower costs for key equipment elements, including fiber optics, CO2 laser cutter, and e-beam systems, as well as computing power and storage.

The technology has been lauded as a means to rethink design, digitise manufacturing, produce to demand, and customise products. Still, despite lofty claims as to the opportunities presented by the technology,3 penetration and use is still limited to certain industries and a relatively small number of applications. While the industries applying 3D printing are disparate, the factors driving the adoption and deployment of 3D printing are similar, as we found in our research with key actors along the complete 3D printing value chain – from raw material providers, to manufacturers, and logistics service providers.

We find that the core opportunities of 3D Printing emerge on three fronts: enhancing innovation in the design process as well as the actual design, embracing responsiveness and customisation, and mitigating operational complexity.

First and foremost, 3D printing enables firms to make products that are not feasible via other techniques. Traditional manufacturing processes like injection moulding and casting have a concrete limitation: they require that product designs be translated into physical artefacts that then form the basis of the manufacturing process. 3D printing allows for a direct translation from design to manufactured product, enabling significant time savings for low volume products.

Secondly, the standardisation of the design interfaces associated with 3D printing opens up opportunities to embrace the customer as a co-creator in the design process.4 Digitisation facilitates obtaining customer input from remote locations, visualisation of the product prior to production, and rapid translation of the customised design into the final product.

Finally, 3D printing comes into its own for complex high-value added product mixes, either because of low volume or one-off applications, or when extensive customisation is required. Beyond allowing for novel product designs, 3D printing offers short set-up times, and can eliminate the need for specialised dies, casts, and other equipment. This is most beneficial at this point in time, for products characterised by low and infrequent demand. Follow print to peer official website here.

While the opportunities related to 3D printing are widely acknowledged, our research also identified key challenges that prevent firms from fully embracing 3D printing (for a summary of key opportunities and challenges see Table 1 below). The main focus of this article therefore is to define the business models that underpin 3D printing: in the light of the opportunities that 3D printing brings, how can firms derive value from it?

How to make it work

3D printing is not for everyone. There are significant risks posed by potential shifts in the boundaries of the firm as well as control over IP, and the technology is still high cost relative to other manufacturing options. Firms should undertake three steps to identify the respective potential and risks 3D printing offers to them: (1) define the opportunity in terms of time, cost and variety, (2), set the boundaries, and (3) situate 3D printing within the organisation. Let us look at each in turn.

1. Define the opportunity in terms of time, cost, and variety. Firms need to undertake a comprehensive analysis comparing 3D printing to existing processes with respect to requisite throughput time, cost of design, production, and aftermarket, and opportunities to generate value from increased variety. A firm level steering committee with members from design, manufacturing, legal, and sales can articulate and provide oversight of the firm’s overall strategy in this space. As a first step, this steering committee should identify where the firm’s value add can be enhanced with respect to design, customisation and responsiveness, and its cost structure can be improved via reduced complexity. This will help identify the firm’s technological gaps and where it wants to build strength. This facilitates decisions, not just with respect to technological investments, but also insight on labour force requirements and skill sets that need to be developed. It should further involve a focused discussion on the associated IP, and in particular, the implications of shifting to a design model where designs incorporate both material and process information. The steering committee can also help coordinate the sharing of information across the lines of business, enforce standardisation of digital files and practices, and prioritise investments. This will most likely involve discussions, not just of 3D printing, but the broader implications and opportunities presented by digital manufacturing. The outcome of this is not where is 3D printing possible, but where does it enhance the value proposition of our product? This value derives from two sources: externally by providing superior designs, or more customised products, or from increased responsiveness, both in terms of design speed, and delivery to customer.

An advantage of establishing a cross-departmental firm-level steering committee is that it signals very clearly that 3D printing initiatives are not to be siloed into one “functional box”. Since it affects product design, manufacturing, marketing and supply chain aspects, no one functional area should own it. It requires rethinking responsibility lines and integrating cost assessment across functions. Once the decision is made to go the 3D printing route, design and production knowledge are integrated into a single data file. This allows for distributed, dispersed, or even outsourced production. Given that outsourcing is often cheaper given the internal charge rates at many firms, outsourcing of the final print is increasingly common. This presents a shift in the boundaries of the firm, and poses a concrete risk for the control the firm can retain over its designs.

2. Set the boundaries. Once the value proposition has been defined, it is critical to set the boundaries within which product customisation takes place. Firms need these clear boundaries of “openness” to leverage external creativity – yet retain control of key aspects of the product. Shapeways, for example, allows customers to upload and sell their designs through its website. However, the available materials are prescribed by Shapeways and it also sets technical boundaries of the product that can be manufactured. A key requirement here is to shift the decision on technological choice as close to the customer as feasible. This facilitates the discussions needed to ensure customer buy-in that the technology is a viable one for the applications under consideration. Equally important, it provides customers with the opportunity to help inform the most productive ways in which the firm can use 3D printing to enhance design attributes and customisation, and to address complexity considerations that directly touch the customer. The opportunities will be greatest where design time lines are important and designs can take advantage of the unique attributes of 3D printing, customisation and responsiveness are valued, and complexity with respect to either inventory or logistics can be mitigated. In many instances, the opportunities will present first for those products where lower volumes and high value-added justify the necessary investments. However, as noted in our introduction, costs are falling rapidly and the technology is advancing rapidly. Pro-actively and systematically exploring 3D printing’s role in higher value-added business lines opens the doors to developing the expertise and insight to ensure the technology can be deployed more broadly as cost falls, the technology improves on the speed and reliability front, the range of materials that can be printed increases, and the ability to incorporate multiple materials (e.g. printing of plastics alongside electronics) is enhanced.

3. Situate 3D printing in your organisation. The final step in a firm’s journey to adopting 3D printing is the decision where to situate it within the organisation. As we outlined above, 3D printing merges design, manufacturing and supply chain considerations. Thus it must not be “owned” by one functional area. A fundamental decision is whether to become a user and build internal capacity, rely on contract manufacturers to provide the printing capability, or shift the printing and inventory management responsibility to a supply chain integrator. It is not uncommon for a firm to select a combination of the three for different elements of the business. For example aerospace manufacturers do operate in-house 3D printing facilities but concurrently rely on a firm specialising in laser sintering for instances where its internal capacity is fully utilised, as well as for some technologies it has little experience with. In a similar vein, we found car manufacturers that use 3D printers in core areas of its business related to prototyping in its R&D facility, but relied on Materialise to print the one-time run of special masking jigs needed for the painting process. Given that this was a one-off need, it did not make sense to produce the jigs in-house, and it made more sense to rely on a firm with the in-house capacity to handle a large order rapidly. In general, we found three ways in which firms can harness the benefits of 3D printing for their operations: (1) develop an internal capability, (2) use contract 3D printing providers, or (3) outsource to supply chain integrators.

Develop internal capability

Users become operators of 3D printers by developing their own 3D printing capacity to design and produce fully-customised parts in-house. This can cover both industrial and personal consumption. An entirely integrated value chain targeting the personal end-consumer is demonstrated by the production of hearing aid cases by several auditory acoustics specialists. In the case of hearing aids, firms take silicon casting of a customer’s ear at its local affiliates. In a centralised facility specialists 3D-scan these silicon castings and use CAD software to render a digital design that is used to print a custom hearing aid case. The hearing aids are then delivered to the local affiliates where the frequency parameters are adjusted and the customer is taught how to use the hearing aid. With the aid of digitisation of the design process and 3D printing, this reduces the production time from four days to as few as two workdays. The primary time advantage comes from printing overnight after the design process is completed during the day. Before 3D printing, blanks were manually poured out of plaster moulds to develop the hearing aid housing. Because of the reduced manual intervention, not only are the products produced more rapidly, but at substantively lower cost.

Like their counterparts catering to the consumer market, industrial users can benefit from 3D-printed parts. For most applications the 3D printing technology is used on a stand-alone basis and not part of a manufacturing flow. A key requirement to a broader application of 3D printing technology is the ability to integrate it into existing technological flows. Hard- and software-wise 3D printers may need to move towards an open platform to allow it to integrate fluently into existing processes so that additive and subtractive technologies interact digitally and automatically. Equally importantly, speed and throughput need to increase if the technology is to be used for higher volume applications. Although 3D printing is sometimes argued to be a technology anybody can use, the different 3D printing procedures and machines require varied levels and types of expertise. To fully understand the potential of 3D printing, firms need to explore the materials and technological options that are applicable to their specific needs. Deep understanding of the different technological options can be garnered by deploying them on lower volume applications. This will provide the requisite insight on which technologies to deploy at larger scale as increases in throughput speed and cost declines continue.

Use contract 3D printers

The role of tacit knowledge in the 3D print process is often underestimated. Considerable effort and knowhow is needed to both prepare a part for printing and to process it to attain the appropriate finish and material characteristics after the print is done. Contract 3D printers offer 3D printing and related value added services to third parties. These services are most pronounced in the consumer market. Online marketplaces and printing services such as Shapeways, Sculpteo and i.materialise emerged concurrently with the first private home-based 3D printers. These businesses models have moved 3D printing towards a commodity service by providing access to industrial 3D printing capacity to the masses. On that level the technology is increasingly accessible, affordable, and requires relatively little knowledge to set up. Similar to copy shops as well as photo labs, the margins on offering just printing services are slim and contract 3D printer need to provide value added services differentiating them from their competitors and home-based users.

In marked contrast, contract printers for professional as well as industrial users are still maturing. Leveraging technical capabilities in pre-processing, printing, and post processing, the firms can add superior value for every printing process. These specialised 3D printing firms can aggregate orders to derive economies of scale by filling build rooms and maximising machine utilisation. As they build expertise, these firms can also deploy their know-how by offering consulting services. For example, Belgium-based Materialise analyses the product portfolios of its customers to identify parts that are technical suitable for and can benefit from 3D printing. In the same way, superior value can also be derived by offering a wide set of technologies. As noted earlier, there are multiple ways to generate 3D prints, and a number of Materialise’s customers may have their own 3D printing capacity, yet may turn to Materialise for a particular print process or material expertise that is lacking in house. The encapsulation of design and manufacturing process in a single digital file allows cost structures to be more transparent. This enables a shift in the decision process on where to situate manufacturing to factors like quality assurance, IP control, country of origin requirements, and so on.

Outsource to a supply chain integrator

Beyond traditional contract manufacturing, 3D printing offers the ability for firms to rethink not just the way its parts are manufactured, but also where they are produced. Here logistics service providers are gearing up to become supply chain integrators that can deliver both manufacturing and inventory management. Logistics service providers are predestined for offering 3D printing services. Adding to their logistics, warehousing, and maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) services, integrators could incorporate printing capacity into their integrated supply chain services. Building a one-stop service strategy, own printing capacity opens up the opportunity for entirely new services to complement the logistic functions. How such a model could look like is shown by UPS’s efforts with the startup CloudDDM. CloudDDM’s goal is to position 100 3D printers at UPS’ worldport hub in Louisville. The concept foresees that orders that arrive prior to six pm and require less than four hours printing time will be manufactured at the hub and be delivered by UPS’s transportation business the next day. Contract 3D printers can similarly explore integration into a customer’s production process. The current product portfolio of most integrators with regard to manufacturing value-added service is still limited to packaging and minor pre- and post-assembly. A potential evolution for these integrators is to build on those existing services to deliver the integration of the entire process. As firms move in this direction some challenges remain to be addressed, including those related to warranty and liability risk. All global logistics service providers are exploring ways how to 3D print key components locally in their warehouses, but so far concerns regarding liability often prevail.

Where to from here?

3D printing captures the imagination of many, yet it is important to get past the hype and to identify the true value proposition it may offer. On a strict unit cost comparison, 3D printing cannot compete with traditional manufacturing at scale, so the question one has to ask is: what benefits does it offer in terms of product innovation, responsiveness and customisation, as well as reducing operational complexity? Do these outweigh the risks entailed in opening up access to the design file, and potentially even allowing third parties to alter the design? These questions are not straightforward, and there are no generic answers. Firms need to systematically assess the specific advantages and risks associated with 3D printing. As part of this, they need to establish clear boundaries on where they will allow access and customisation of their designs. The decision process needs to include not just what – if any – capabilities will be developed in-house, but also the potential benefits of drawing on contract manufacturers and logistics service providers.

About the Authors

Matthias Holweg is Professor of Operations Management at Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, UK. Prior to joining Oxford he was on the faculty of the University of Cambridge and a Sloan Industry Center Fellow at MIT’s Engineering Systems Division.

Matthias Holweg is Professor of Operations Management at Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, UK. Prior to joining Oxford he was on the faculty of the University of Cambridge and a Sloan Industry Center Fellow at MIT’s Engineering Systems Division.

Kai Hoberg is Associate Professor of Supply Chain and Operations Strategy at Kühne Logistics University, Germany. Before returning to academia he was a project manager and strategy consultant at Booz & Company.

Kai Hoberg is Associate Professor of Supply Chain and Operations Strategy at Kühne Logistics University, Germany. Before returning to academia he was a project manager and strategy consultant at Booz & Company.

Frits K. Pil is Professor of Business Administration at the Katz Graduate School of Business and Research Scientist at the Learning Research and Development Center at the University of Pittsburgh, USA.

Frits K. Pil is Professor of Business Administration at the Katz Graduate School of Business and Research Scientist at the Learning Research and Development Center at the University of Pittsburgh, USA.

Jakob Heinen is a doctoral candidate at Kühne Logistics University, Germany.

Jakob Heinen is a doctoral candidate at Kühne Logistics University, Germany.

References

1. We use the term ‘3D printing’ as it is the most commonly understood term describing this class of additive manufacturing (AM) techniques, and as a subset of the broader class of direct digital manufacturing (DDM) techniques (which includes both additive and subtractive processes).

2. M. Fitzgerald, “With 3D printing, the shoe really fits”, MIT Sloan Management Review (May 15, 2013). http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/with-3D-printing-

the-shoe-really-fits/

3. See for example R. D’Aveni, “The 3D printing revolution”, Harvard Business Review 93 (May 2015): 40-48, and others.