By David De Cremer and Tian Tao

In this article, the authors trace giant telecom Huawei’s success to its founder’s commitment to compassionate leadership. In a fast modernised wold, how do ancient Confucian and Buddhist teachings of compassion drive you, your business, and the people around you not only to success but to a better life?

More and more voices in the business world are asking to bring more humanity back to the workplace. A desire has emerged to consider employees in their totality, as the person they are, and the stories they bring with them. Where does this sensitivity come from? Are workplaces really that bad? According to Robert Sutton, a Management Professor at Stanford University, workplaces are dominated by a culture of winning and being an asshole. In his book “The No-Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn’t”, he provides clear examples that as long as you get good results, it is more or less ok for the US corporate world to be an asshole. In line with Sutton’s assertion, research has, for example, illustrated that almost 14 percent of all US employees are confronted with an abusive supervisor,1 and that this dysfunctional type of leadership costs companies an estimated 23.8 billion dollars annually (due to absenteeism, health care costs and decreased productivity).²

The contemporary sentiment thus seems to be that workplaces need to foster more positive relationships. The existence of positive relationships brings many benefits, including improving employees’ physical and psychological health, raising their feelings of optimism, enhancing more learning behaviours, and fostering creativity and trust. To achieve these outcomes it is suggested that we need leaders that can take the perspective of their employees and act in encouraging and respectful ways so that resilience for both employees and organisation is built over the long term. As a consequence, leadership scholars have identified the notion of compassion as important to contemporary leadership practices. There is no doubt that compassion is an important virtue and can reveal many positive benefits, but is it really something that will strengthen leadership effectiveness?

It is a common phrase in the business world that with great power comes great responsibility and one of these responsibilities is to learn to exercise power in controlled and compassionate ways. In fact, with a focus on sustainability at all levels of business and society, the leadership type for the 21st century may well be the compassionate one. Why? What are its benefits? Interestingly, research is demonstrating increasingly that leaders recognising the feelings of others and using that emotional information to support and empower them has positive relational effects that make leaders truly effective. In his book “Leaders eat last: why some teams pull together and others don’t”, Simon Sinek argues that true leaders care about the well-being of others and are willing to be compassionate towards the concerns of those others. This kind of attitude facilitates the flow of the neurochemical oxytocin, which makes that positive and bonding relationships are formed. In other words, compassionate leadership is effective because it promotes trust in the work place, which leads to many positive work outcomes and long-term success. Neuroimaging research has indeed demonstrated that compassionate leaders motivate employees to trust their bosses,3 and make them display high loyalty to those leaders being compassionate.4

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

On the Philosophical Origins of Compassion

One country in which compassion plays an important role in their life and society philosophies is China. The Chinese consider compassion to be a kind of spiritual way of looking at the world and is thus of essence in how you treat others. In light of this interest, it is therefore maybe no surprise that the movie “Hacksaw Ridge”, which features a soldier who did not want to kill any other soldier while saving so many others was praised highly in China. The soldier’s view of looking at and acting in the world embodies the spiritual value of compassion. Importantly, the idea of taking care and being concerned about the well-being of others features prominently in the teachings of Confucius and Buddhist. In both philosophies, compassion is considered key to regulate social interactions in positive and thus trusting ways.

First, building business relationships in China is a function of how you can manage guanxi, which are interpersonal ties build around mutual commitment, loyalty, and obligation. If one is successful in building guanxi it will result in the development of mutual trust and closer bonds. What is interesting to know is that the concept of guanxi stems from the tradition of Confucianism. Its founder Confucius is considered a thought leader, political figure, and educator, who founded the Ru School of Chinese thought. He focussed primarily on understanding models of social interaction and in this context he developed his social philosophy which revolves around the concept of ren, or, also referred to as “compassion”. According to Confucius it was the duty of society to reinforce the value of compassion. As such, because of the centrality of guanxi in achieving business success in China, compassion should be one of the more important values in business interactions.

Second, the practice of compassion for any leader is also important in Buddhist teachings. According to the Buddha to realise enlightenment, an individual needs to achieve both wisdom and compassion. Wisdom is considered as having insights into what you do, a kind of consciousness of your being. This quality sets the stage for the even more powerful influence of being willing to consider the suffering from others and to help remove those negative feelings. Neuroscience research in fact has demonstrated that when conducting brains scans on the brains of Buddhist meditators that their meditation that focusses on compassionate feelings “lights up” the left prefrontal cortex. This part is associated with feelings of joy happiness, enthusiasm and resilience.5 As such, individuals – such as leaders – engaging in compassionate actions and thoughts are able to create more positive interactions.

Do We Recognise Compassionate Leadership in Chinese Work Cultures?

A company that is illustrative of the emergence of compassionate wisdom as a way to achieve business success is the Chinese telecom giant Huawei. The company is considered to integrate Chinese philosophies with the more rational Western style of management. This mix of East and West in demonstrating leadership has resulted in global business success as the company surpassed Ericsson as the world leader in terms of sales revenue and net profit in 2012. Why would compassion play a role in explaining their business success? One answer to this question concerns the beliefs and actions of their founder and leader Ren Zhengfei.

According to the Buddhist school of thought, compassion arises from wisdom. We noted earlier6 that a reason why Huawei has been able to grow and continue to reinvent themselves over the last 30 years is wise leadership. Huawei’s focus on wisdom as a key aspect of continuous growth is without a doubt defined by its founder’s love to study and develop knowledge across borders. As John F. Kennedy once noted “Leadership and learning are indispensable to each other”, and Ren Zhengfei embodies this wisdom in many of the things he does. An important facet in this knowledge process is that Ren Zhengfei is known as a storyteller who regularly talks about his views on business, life and philosophy. In other words, he reflects on past achievements and future ambitions to keep people conscious about the challenges they face and at the same time to stay humble. This way of looking at business success reflects in a certain way the meditation practices of Buddhists that makes people develop their own understanding and become more sensitive to the suffering of others. Ren Zhengfei is a leader who follows exactly this path. It has been documented that in the journey of developing Huawei, from 1987 (the year the company was founded) until now, he suffered several times from depression, anxiety and uncertainty about the existence of Huawei. He attributes his forward and yet reflective style of leadership to the fact that he was able to put his suffering in perspective to connect to the suffering of others. In addition, acknowledging and understanding suffering has for him a clear purpose, which is to make Huawei survive as a leading business force.

Ren Zhengfei, founder of Huawei, at World Economic Forum, Davos, January 2015

© Huawei.com

Building on this leadership philosophy, an important leadership assumption in Huawei is that leaders need energy – they have to be spiritual in working with the energy of and faith in others. This implies that leaders cannot pursue perfection all the time else they will lose touch with the values and passion that motivates them. The same counts for their employees. This makes that a clear sense of awareness exists in the company that leadership cannot wear out employees and therefore they want and need to be compassionate about their failures. In fact, the idea exists that the common assumption that heroes are perfect beings achieving the biggest successes (as often portrayed in blockbuster movies) is a false one. Indeed, Huawei stands for the belief that imperfect heroes are also heroes – maybe they are even the real heroes. This kind of thinking advocates the need to know the flaws of your employees and to show tolerance to their failures, which requires a sense of compassion. It also means that leadership is not seen as an activity to change the nature of people, but rather trying to respond to their concerns and suffering with the aim to energise their own specific talents. As Ren Zhengfei has suggested “let’s not wash a piece of black coal into a white one”, implying that spending time and effort to changing people is not the way forward. We have to accept people and work with who they are.

The consequences of this type of compassionate leadership are clearly documented in the working of the company. First, one of the most well-known facts of Huawei is that it is an employee-owned company. When Huawei was founded Ren Zhengfei designed the Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). In this ESOP, he holds 1.42% of the company’s total share capital whereas 81,144 employees (data as of December 2016) hold the rest of the shares. The underlying motivation was Ren Zhengfei’s focus on compassion to the working and financial situation of his employees. Specifically, Ren Zhengfei considers Huawei a collective effort that implies sharing wealth to ensure everyone will have their share.

Second, as a company working in the ICT industry the pursuit of innovation is a key issue. To achieve the most creative solutions, Huawei has decided to use 30% of their R&D investments for fundamental scientific research. Interestingly, it has further been agreed that of this 30% investment failure in 50% of the projects will be accepted. This decision is motivated by the recognition that tolerance needs to be shown to failure and suffering and especially so if your ambition is to find new and creative ways of working.

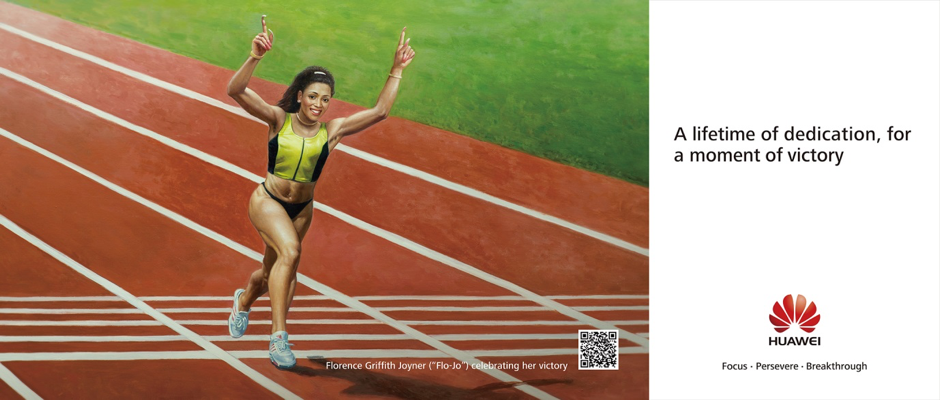

Finally, showing tolerance towards failure and weaknesses as part of a compassionate leadership style was maybe best illustrated in 2016 by Ren Zhengfei’s then-decision to use an image of Olympic champion Florence Griffith Joyner (“Flo-Jo”) in Huawei’s Breakthrough advertising campaign (see picture below).

His choice for this picture was criticised because although Flo-Jo radiates strength and success (she is still the world record holder on both the 100 and 200 meters sprint), in her life time (she died in 1998 at the age of 38) she was repeatedly accused of performance-enhancing drug use. Although Flo-Jo passed all drug tests suspicion concerning her achievements always remained. So, from a marketing point of view, many people posed the question why Huawei chose her for its advertising campaign. A reason for this is that the choice of this picture reflects a compassionate leadership style with the aim to convey the message that tolerance towards failure is needed and that effort needs to be put in understanding people’s suffering. In management terms this view point translated into the practice of recognising and treating with respect the failures of your employees, because if you do not do so why would they be willing to go out on your behalf and take risks? Illustrative of this idea is Ren Zhengfei’s reply to one manager’s public note of self-reflection: “We need to show tolerance toward junior managers in the same way that the US showed tolerance toward the failure of Douglas MacArthur in the Pacific Theater. No one can always win, and there is no success without failure. Failure is the mother of success.” It is thus clear that with the choice of Flo-Jo as one of the pictures in their advertising campaign Ren Zhengfei emphasised the importance of compassion as an organisational value.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

David De Cremer is the KPMG professor of Management Studies at the Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, UK, where he heads the department of Organisational Leadership and Decision-Making. He is also an advisor to the Ethics-based Compliance Initiative at Novartis. Before moving to the UK, he was a professor of Management at China Europe International Business School in Shanghai. He is the author of the book Pro-active Leadership: How to overcome procrastination and be a bold decision-maker (2013) and co-author of “Huawei: Leadership, culture and connectivity” (2017).

David De Cremer is the KPMG professor of Management Studies at the Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, UK, where he heads the department of Organisational Leadership and Decision-Making. He is also an advisor to the Ethics-based Compliance Initiative at Novartis. Before moving to the UK, he was a professor of Management at China Europe International Business School in Shanghai. He is the author of the book Pro-active Leadership: How to overcome procrastination and be a bold decision-maker (2013) and co-author of “Huawei: Leadership, culture and connectivity” (2017).

Tian Tao is co-director of Ruihua Innovative Management Research Institute at Zehjiang University. He is also the author of the book “Huawei: Leadership, culture and connectivity” (2017) and founder and Editor in Chief of Top Capital magazine.

Tian Tao is co-director of Ruihua Innovative Management Research Institute at Zehjiang University. He is also the author of the book “Huawei: Leadership, culture and connectivity” (2017) and founder and Editor in Chief of Top Capital magazine.

References

1. Schat, A. C. H., Frone, M. R., & Kelloway, E. K. (2006). Prevalence of workplace aggression in the U.S. workforce: Findings from a national study. In E. K. Kelloway, J. Barling, & J. J. Hurrell (Eds.), Handbook of workplace violence (pp. 47-89). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

2. Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A., & Lambert, L. S. 2006. Procedural injustice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 59, 101-123.

3. Boyatzis, R.E., Passarelli, A.M, Koenig, K., Lowe, M., Mathew, B., Stoller, J.K., & Phillips, M. (2012). Examination of the neural substrates activated in memories of experiences with resonant and dissonant leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(2), 259-272.

4. Qiu, T., Qualls, W., Bohlmann, J., & Rupp, D.E. (2009). The effect of interactional fairness on the performance of cross-functional product development teams: A mulit-level mediated model. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(2), 173-187.

5. Ekman, P, Davidson, R.J, Ricard, M., & Wallace, B.A (2005). Buddhist and Psychological Perspectives on Emotions and Well-Being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 59-63.

6. Tao, T., De Cremer, D., & Chunbo, W. (2017). Huawei: Leadership, culture, and connectivity. London: Sage.