By Vanina Farber, María Helena Jaén and Patrick Reichert

The logic of sustainable finance is simple; tell me where you put your money, and I will know what matters to you. But how do sustainable investors actually make their investment decisions and what are the strategies available to them?

Business plays an essential role in tackling social and environmental problems. The typical approach emphasizes the need for companies to create social and environmental value while also generating profits–commonly referred to as the triple-bottom line.1

In this paradigm, investors take on responsibility to positively influence the wellbeing of society and health of the planet by selectively allocating their capital. The umbrella term of sustainable finance captures how investors engage with companies over their environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. But how do investors decide whether to invest, divest, or engage with firms on sustainability issues? What challenges do investors face in promoting corporate change toward more sustainable business models?

The Sustainable Finance Menu

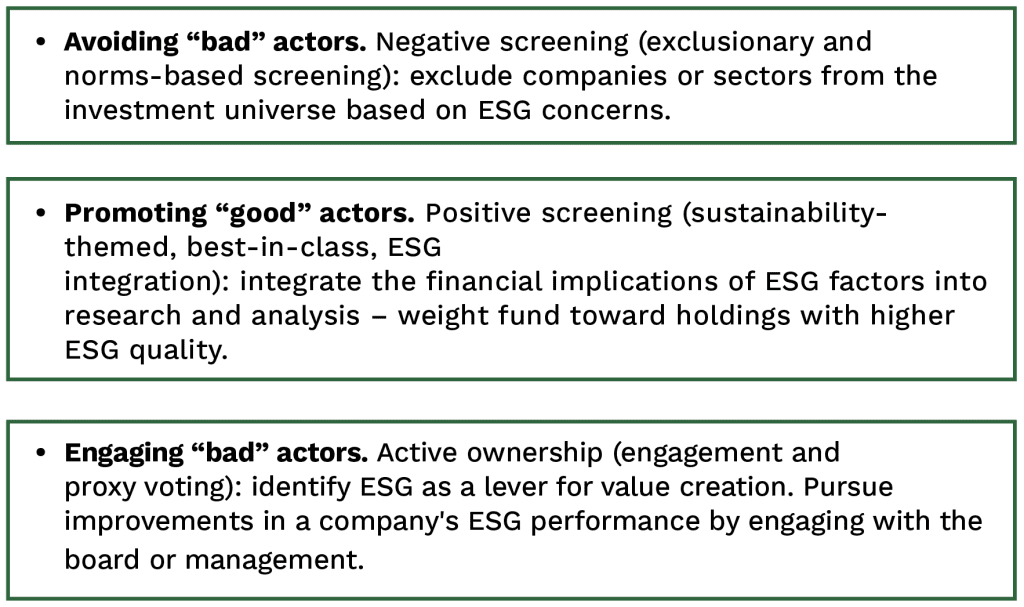

Most agree that for asset managers to drive corporate transformations toward a greener, more inclusive, and prosperous society, they first must consider the menu of strategies available when integrating ESG issues into investment decisions. The three most popular strategies include:

Exclusion

Asset managers can exclude companies based on a negative/exclusionary and norms-based screening or invest and engage with companies (active ownership). Under the negative screening strategy, portfolio managers apply ESG exclusion to remove companies associated with crucial social or environmental issues, such as controversial weapons, tobacco companies, thermal coal revenue exposure >10%, UN Global Compact Principles non-compliance – human rights violation, forced labour, and corruption allegations.

Positive Screening

Research has shown that firms focusing on material ESG issues can significantly outperform firms with poor sustainability ratings.2 Material topics include those that can reasonably be considered important in reflecting an organization’s economic, environmental, and social impacts, or influencing the decisions of stakeholders. By contrast, firms that rate high on immaterial sustainability issues do not outperform other firms. The central thrust of this argument is that ESG integration enhances returns by injecting new and forward-looking insights into the investment process. Additionally, public sentiment momentum matters to generate alpha: the market undervalues strong ESG performance where public sentiment is negative and overvalues strong ESG performance where public sentiment momentum is positive.3

Active ownership

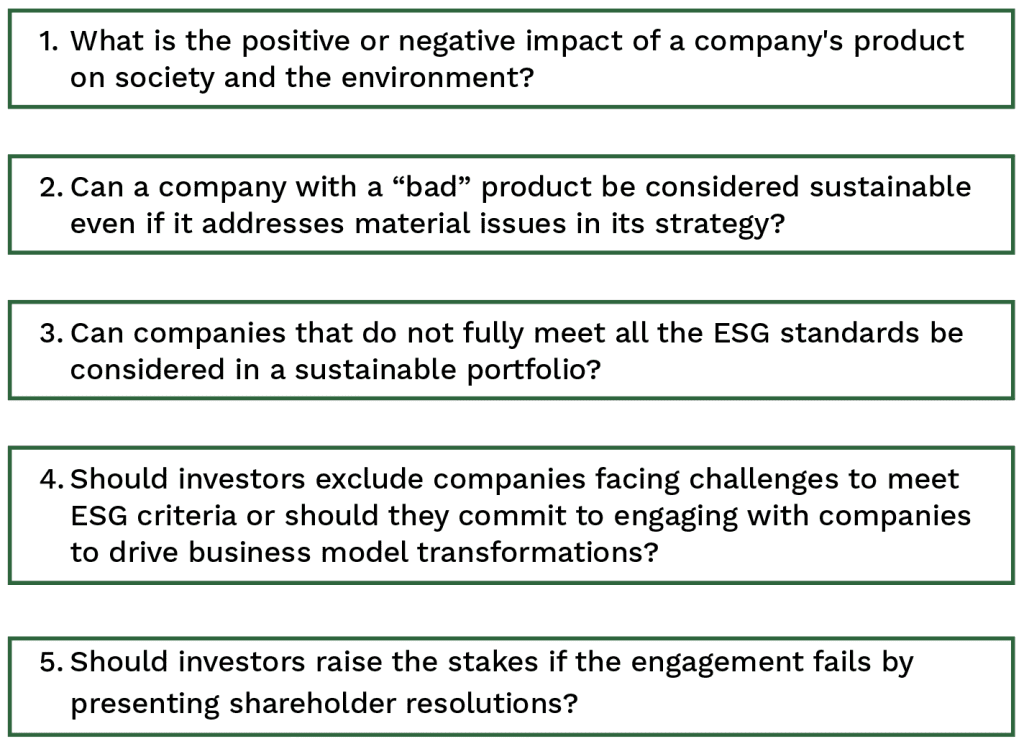

Engagement involves a constructive dialogue to discuss how the companies manage ESG risks and seize business opportunities associated with sustainability challenges.4 Nevertheless, the engagement process must go beyond a box-ticking exercise for compliance to genuinely catalyze sustainable business models. Engagement implies direct communication between investors and companies and shareholder resolutions and proxy votes engagement tools when needed. Sustainable investors focus their engagement activities with listed companies on material ESG issues, creating long-term shareholder value. Some typical questions that face investors include:

Making sustainable investment decisions

Although these strategies are intuitive and straightforward on the surface, in practice their application is much more nuanced. For instance, does Tesla, a company with a “green” product but questionable labour practices, belong in a ESG portfolio? Can a tobacco company such as Phillip Morris International (PMI), which is transforming its business model, be considered as a sustainable investment and therefore eligible to engage with? What does a Paris-aligned portfolio that seeks to comply with the 1.5°C look like?

Making sustainable investment decisions is about creating sustainable businesses in an increasingly stakeholder-oriented society that seeks to improve the welfare of shareholders, employees, clients, suppliers, society, and the planet. ESG integration decisions are difficult because, in most cases, the options are not black and white. To help sustainable investors evaluate and reflect on their options and the course of actions that best meets their obligations, we have developed an IMD case series on sustainable finance that equips the decision makers of the future with the tools to start answering these questions.5

About the Authors

Vanina Farber, elea Professor of Social Innovation, IMD Vania is an economist and political scientist specializing on social innovation, sustainability and impact investing, with also almost twenty years of teaching, researching and consultancy experience, working with academic institutions, multinational corporations and international organizations. She is the holder of the elea Chair for Social Innovation. She has recently published a book on that addresses impact investing and social entrepreneurship, “The elea Way” with Peter Wuffli, founder and chairman of the elea Foundation for Ethics in Globalization.

Vanina Farber, elea Professor of Social Innovation, IMD Vania is an economist and political scientist specializing on social innovation, sustainability and impact investing, with also almost twenty years of teaching, researching and consultancy experience, working with academic institutions, multinational corporations and international organizations. She is the holder of the elea Chair for Social Innovation. She has recently published a book on that addresses impact investing and social entrepreneurship, “The elea Way” with Peter Wuffli, founder and chairman of the elea Foundation for Ethics in Globalization.

María Helena Jaén, Honorary Professor, Universidad de Los Andes Maria Helena is an experienced professor, researcher, and consultant with a demonstrated history of working in education management and a deep understanding of the Latin America business context. Drawing on managerial experience in the private and public sectors, she has authored several publications in top academic journals and created a portfolio of pedagogical materials and case studies.

María Helena Jaén, Honorary Professor, Universidad de Los Andes Maria Helena is an experienced professor, researcher, and consultant with a demonstrated history of working in education management and a deep understanding of the Latin America business context. Drawing on managerial experience in the private and public sectors, she has authored several publications in top academic journals and created a portfolio of pedagogical materials and case studies.

Patrick Reichert, Research Fellow at the elea Chair for Social Innovation Patrick conducts research at the intersection of entrepreneurship, finance and social impact, with a particular focus on the mechanisms and logics that investors use to seed investment in social organizations. He is a research fellow at the elea Chair for Social Innovation.

Patrick Reichert, Research Fellow at the elea Chair for Social Innovation Patrick conducts research at the intersection of entrepreneurship, finance and social impact, with a particular focus on the mechanisms and logics that investors use to seed investment in social organizations. He is a research fellow at the elea Chair for Social Innovation.

References

1 https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it, accessed December 1, 2021.

2 Mozaffar Khan, George Serafeim, and Aaron Yoon. (2016). “Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality.” The Accounting Review, November 2016, Vol. 91, No. 6, pp. 1697–1724. <https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51383> (accessed 12 October 2021).

3 Serafeim, George, “Public Sentiment and the Price of Corporate Sustainability.” (12 October 2018). Financial Analysts Journal, 76 (2): 26-46., Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3265502 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3265502

4 “Principal Adverse Impact Statement.” Robeco, July 2021. <https://www.robeco.com/docm/

docu-robeco-principal-adverse-impact-statement.pdf> (accessed 5 September 2021).

5 https://www.imd.org/research-knowledge/case-studies/case-collections/sustainability/