By Guido Stein and Kandarp Mehta

Soft skills, like negotiating, have become increasingly important in creating personal relationships and fostering opportunities for your business’ long-term success. While it is easier to formulate agreements between parties, diffusing differences and managing cooperation from multiple parties are far more complex, yet the most common in today’s business world, even in the daily transaction of our lives. In this article, the authors discuss the techniques on managing and leading multiparty negotiations.

Two sisters are fighting over an orange. Their mother intervenes and discovers that one sister wants to have juice while the other needs the peel to make a pie. The mother appropriately shares the two parts of the orange between the two sisters and both are very happy. You have read this kind of story in many negotiation books. However, to this scenario add another sister who wants the peel for cosmetic use, a grandmother who thinks that the orange is rotten and should be thrown away, a toddler who thinks that the orange is a ball and wants to play with it, and an elder brother who wants the orange simply so that nobody else can have it. That’s a multiparty negotiation for you. It is frequently difficult to identify who wants what and how to get what we want in such a dynamic situation. Let’s try to understand what some of the biggest challenges are in multiparty negotiations.

One of the reasons why we need to understand multiparty negotiations well is that they are lot more frequent than we realise. In our negotiation programmes, we frequently ask participants what kind of negotiations they participate in the most: individual, team, or multiparty negotiations? Rarely do we find a negotiator who mentions multiparty negotiations as a frequent negotiation exercise. However, when we conduct the negotiation simulations, quite often the same negotiators confess that they had not realised how often they engaged in multiparty negotiation situations. Many internal negotiations are varieties of multiparty negotiations: for example, departmental meetings, family meetings to discuss property issues, business or interpersonal conflicts, meetings of neighbours to sort out neighbourhood problems, or even a meeting between a group of friends to discuss where should they go on vacation together.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Identifying Other People’s Interests

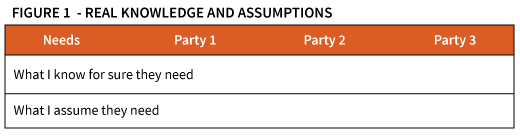

One of the biggest challenges in a multiparty negotiation is to ascertain the interests of everyone at the negotiation table. At the same time, it is important to be able to convey our own interests to everyone else. Quite often in our negotiation workshops, when we organise multiparty negotiation exercises, participants complain that their voices were drowned out or that they were not able to convey their point of view properly. It is very important to manage the negotiation proc ess in such a way that everyone in the negotiation gets an opportunity to take part in the conversation. One of the ways to identify other people’s interests in a multiparty negotiation is preparation. It is very important in this case to identify what we know for sure and what we assume that we know. Look at 1 below. You can use this to identify clearly what you know for sure and what you think you know. There are two reasons for this. The first is to identify what information we have in concrete terms. This will help us work out what questions we will have to ask when we negotiate. The other goal is to prevent us from acting on the basis of sheer prejudice. Quite often in a negotiation, we make assumptions on the basis of our biases about what others want, but these turn out to be false. Figure 1 shows how the needs of others can be analysed before a negotiation.

As we identify needs in this fashion, we can actually frame questions that we will need to ask when we enter the multiparty negotiation.

Power and Alliances

Another important factor that influences a negotiator’s expectations in a negotiation is power. In the case of a multiparty negotiation, power plays a very crucial role. In a dyadic or two-party negotiation, it is easier to identify the needs of each side because comparing the situations and alternatives of only two sides is less difficult. In a multiparty negotiation scenario, it is difficult to assess the situations of everyone else compared to our own. Also, it is important to note the relationships between multiple parties in order to work out what kind of alliances they might be forming.

Forming an alliance before and during a multiparty negotiation is one of a negotiator’s most important tasks.

1. Creating a formidable alliance.

2. Protecting yourself against a hostile alliance.

Strategies for Forming an Alliance

Affinity Map

Generally during negotiations, you have to both create an alliance and protect against hostile alliances. How can a negotiator do both effectively? Once again, preparation is key. As the saying goes, “the more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war”: a negotiator needs to be ready for both situations. The tool we recommend for use in preparing for alliances is a so-called affinity map. This is essentially a visual representation of the proximity of interests of the different parties involved in a negotiation. The aim is to show what kinds of alliances are likely to emerge.

Let’s assume a company’s top management people are getting together for a meeting to decide on the new production budget. The key decision is whether the company should invest in expanding the plant facility. The various executives have different concerns, as follows:

1. The chief executive officer wants to do what is best for the company in the long run.

2. The chief financial officer wants to reduce overinvestment in the plant facility because of higher interest rates.

3. The chief marketing officer believes that increased production will mean more stock and this could lead to higher sales figures.

4. The chief operating officer is of the view that increased production will mean a higher-scale and more efficient production and better management of the facility.

5. The human resources director is concerned that a bigger plant facility will result in increased pressure on existing staff, overtime costs and pressure on immediate recruitment.

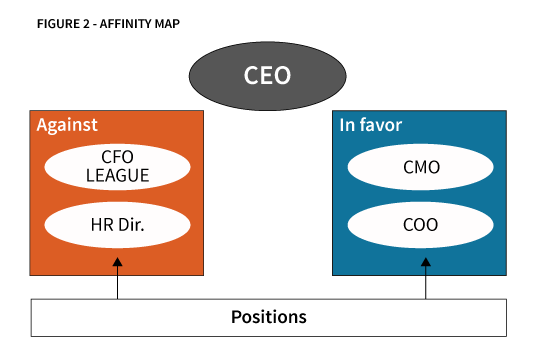

On the basis of the information above, what would each individual’s position be? Obviously the chief marketing officer and the chief operating officer would be in favour of the investment, while the chief financial officer and the human resources director would not be in favour. The chief executive officer has a neutral position and would probably take one side or the other only after more detailed analysis.

If we draw an affinity map about who supports or opposes the facility, the following emerges.

As you can see, we can easily identify who is likely to form an alliance with whom. The example given here is rather crude but explains the concep t of an affinity map very well. Let’s think about the eventual meeting of these five leaders. While the CEO is taking stock of the situation, both the CFO and the HR director will try to convince the CEO about the disadvantages of the investment, while the CMO and the COO will try to persuade the CEO to go ahead with it.

With a tool such as an affinity map, the CFO will realise that she or he has to create an alliance with the HR director, and then collectively, they can put forward strong arguments against the expansion. The CFO also has to make sure that the HR director continues to back that position. Finally, because the other executives are probably more inclined to favour the expansion, the CFO has to make sure somehow that their alliance does not persist.

Listening to Others and Showing You Listen

In a multiparty scenario, in order to understand what people really need, it is very important to listen to them. To listen well, it is important to make sure that the negotiators at the table get enough space and time to express their needs. The best way to ensure that this happens is by taking the initiative in asking questions.

Making Suggestions About the Process

It is important to have control over the negotiation process. One way to achieve that is to come up with a recommendation regarding the process. If other negotiators have not really thought about the negotiation process, then everyone will likely agree to your recommendation. That will give you better control over the negotiation process.

Reaching an Agreement and Making Alliances

Reaching an agreement in a multiparty negotiation is not only complex but also vulnerable to biases and difficulties. Let’s look at an example.

Cunning Dad and the Marquis de Condorcet

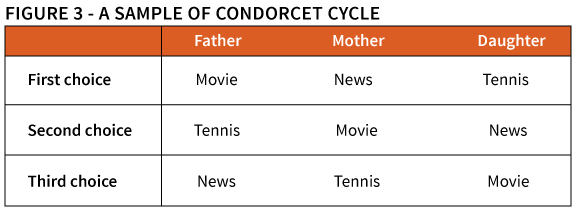

A particular household has three members: the father, the mother, and a teenage daughter. As winter begins, they decide to spend a weekend at a ski resort. They arrive at the resort on a Friday evening and the father is the first one to switch on the TV. To his dismay, he finds that there are only three channels. One channel is showing a movie that he loves, another is showing a live tennis match, and the last one is broadcasting news. The father wants to watch the movie, with his second choice being the tennis match. He is in no mood to watch the news right now. The father knows that his daughter would love to watch the tennis match as she is a very good player. If she cannot watch the match, she would prefer the news. However, she would never watch the movie being shown, as it is a typical romantic comedy, a genre that she hates. The mother does not like tennis. Although she might like the movie that is on, her first choice definitely would be to watch the news.

The father wants to ensure that his choice will eventually win out, but he still wants everyone’s opinion. What should he do? Well, this cunning dad does something unethical. He says to his wife and daughter: “Sweethearts, there is a movie or a tennis match on TV. Which should we watch?” The daughter says: “Tennis!” The wife says: “No! I don’t want to watch tennis at all. I’d prefer something else.” The father tells his daughter: “Well, dear, I’d also prefer the movie to the tennis. And your mom agrees. So why don’t we watch the movie?” They all watch the movie.

If they all knew about all the options from the very beginning, there would be no solution because the father would want to watch the movie, the mother would prefer the news, and the daughter would prefer the tennis. This is known as a Condorcet cycle, named after the 18th-century French philosopher Nicolas de Condorcet, the marquis de Condorcet. In a Condorcet cycle, choices are cyclical in nature (A > B > C > A), so there is no clear winner. To take advantage of such a situation, some negotiators sometimes present the situation in a way that limits the choices available, putting others in a position where they may be unable to make the choice they would actually prefer. You should always be very careful not to fall victim to such a trick (like the cunning dad’s trick) in a multiparty negotiation.

Setting the Agenda and Presenting the Choice

Other important elements in a multiparty negotiation are setting the agenda and presenting choices. Given that there are multiple parties at the negotiation table, it is extremely important to have a say in setting the agenda and also in presenting alternatives. In other words, for a more effective multiparty negotiation, greater control over the process is definitely required. Another reason why it is important to present options is because a negotiator develops a limited perspective when there are multiple options on the table. In a study conducted by Leigh Thompson, participants in a multiparty negotiation were asked, upon finishing the negotiation, how many potential solutions they thought were possible. The negotiation dealt with five different issues and each issue had four or five clearly identified alternatives. The participants’ response was one! On average, people estimated that there were about four alternative solutions possible. In reality, the exercise offered about 50 potential solutions. We call this problem a problem of bounded negotiability. Bounded negotiability refers to our ability to see a limited range of issues as “negotiable.” It is largely influenced by our preparation and how issues are presented in a negotiation. That is why it is important to understand all the issues beforehand and to try to get the complete picture before the negotiation begins.

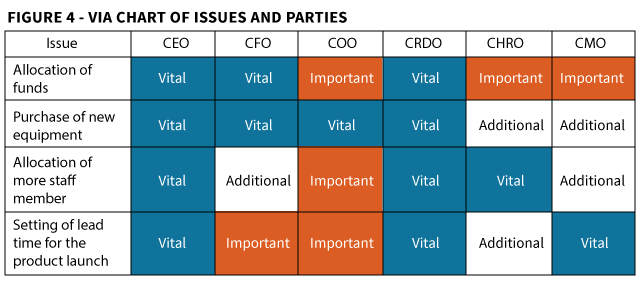

We often recommend that our participants and students use the VIA framework for analysing the needs of different parties at the table. In the VIA framework, participants are encouraged to classify the needs at hand as vital (V), important (I) and additional (A). This classification helps a negotiator manage the time available properly and it helps the negotiator focus on issues that are more important than others.

Let’s look at an example. An executive once told us about a multiparty negotiation in which he had taken part. Imagine that, in a pharmaceutical company, an important negotiation is taking place to decide how much of a budget should be allocated to a new cosmetic product. The issues to be decided are the budget allocation, the allocation of human capital, the purchase of new equipment and the lead time for launching the product in the market. Which issue is likely to generate the most debate in this case? Generally, when we ask this question, the answer we receive is: “The budget allocation of course!” However, the executive who was sharing the story with us drew a VIA chart for all the issues and all the parties present. The following negotiators were present at the meeting: the CEO, the chief financial officer, the chief operating officer, the chief research and development officer, the chief marketing officer, and the chief human resources manager. In this scenario, the allocation of human capital is a vital decision for the CEO, COO, and CHRO. The budget allocation is an essential decision for the CEO, CFO, and chief R&D officer. Below is a complete list of how each individual ranked each issue.

What do we see in this chart? Well, apparently the decision about whether to buy new equipment for the research project was a vital issue for most of the negotiators (four out of six), while the budget allocation was a vital decision for only three of them. Eventually, as the executive predicted, it was the decision about the equipment that occupied most of the time at the meeting. One reason why it created a little bit of conflict was because almost everyone had assumed that it might not be a very important issue for the rest of the negotiators. Hence, they all broached the subject slightly later in the conversation and eventually, this created a significant amount of chaos and conflict in the team. Along with the affinity map, a VIA matrix for the negotiating parties helps to identify potential allies very quickly.

Establishing the Core

The owner of a family enterprise once shared an interesting story with us. The eldest brother in the family ran the business operated across Central America and the enterprise. This brother – let’s call him Ramón – was almost 70 and wanted to delegate more responsibilities to his two younger brothers and their six sons. (Each of the three brothers had two sons.) Ramón was the president and CEO of the company while his two brothers were vice presidents. Ramón’s two sons and four nephews were all involved in the business and looked after different operations. However, Ramón wanted to restructure the business into different autonomous business units and allow each son and nephew to take on more of a leadership role in those units. He also wanted his two brothers to take over his role gradually, with one brother becoming the company president and the other brother the CEO. For a few months, Ramón talked to everyone individually, but without revealing his plans, in order to find out what everyone really wanted both personally and professionally. Finally, he came up with a plan. At one of the quarterly meetings for the performance review, Ramón called a meeting of his brothers, sons, and nephews and unveiled his plan for restructuring the business. Everyone welcomed the idea of change in the organisation and also showed willingness to take on greater responsibility. However, as Ramón told them what he thought everyone should be doing, the enthusiasm started to wane. In fact, the meeting came to no conclusion, and Ramón had to stop talking about restructuring because he feared that tensions might increase and he did not want a rift in the family. He was puzzled that his idea had been received so coldly, since he had thought everything through in such detail and had tried to do what was in everyone’s best interest. After a few months, everyone got together again at the wedding of an employee’s daughter. Ramón felt it was safe to mention restructuring because, even if someone got angry, no one would want to make a scene at the wedding. This time, though, Ramón could not talk to everyone at the same time. At his table, he was seated with his wife, his two brothers and their wives. Ramón started talking to his brothers about his plan, and then their wives also got involved in the conversation. Ramón’s wife was very dear to both of his brothers, who treated her like an older sister. By the end of lunch, Ramón had convinced his brothers and secured a commitment from them and their wives that they would do everything possible to persuade their children. Slowly, over the next two months, Ramón convinced his sons to back the restructuring plan and eventually he had a commitment from everyone. He had made some tweaks to his plans as well. “I wanted to make everyone happy at the same time but I was wrong,” he said. “I learned a very important lesson of leadership, just as I was about to leave the leadership position. No matter how much you wish others well, eventually you have to build consensus slowly. You can’t win all of them over at once.”

Generally, it is difficult to form a coalition of everyone all at once because of a lack of trust among group members. It is important for the negotiator first to win the trust of a few important members (the ones closest in the affinity map) and to establish a core. Having a core makes it easier to gain the trust of new members, and it also makes it easier to expand the coalition without much disruption.

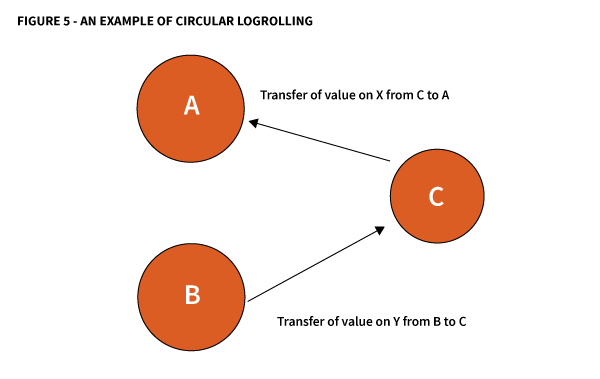

Circular Logrolling

Another advantage of establishing a core is circular logrolling. This means having trade-offs with other members. Think of a three-party situation where A and B have established an alliance already and they want C to enter the alliance as well. However, to achieve this, A needs C to back down on a particular issue X, where A and C have contradictory positions. In other words, A needs C to back down in favor of A. However, there is another issue Y, on which B can back down in favor of C. In this case, A can convince C to give up on X in return for Y, where B will back down. Such circular logrolling or trading off is possible when a negotiator has already established a basic alliance and is trying to expand it.

Understanding Others

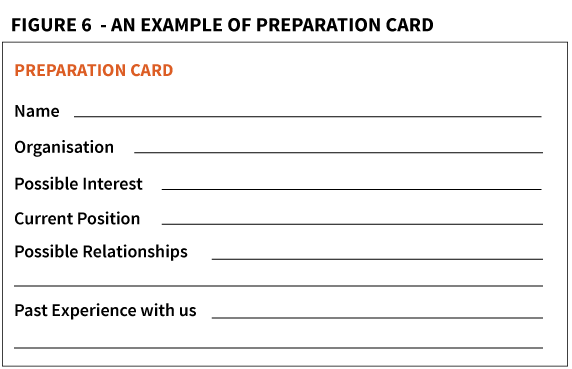

In order to establish a formidable coalition, it is very important to understand who is at the table. A quick analysis using a uniform structure can be helpful in getting to know one’s counterparts at the table in advance. Pictured above is an example of a card that can be used for a quick analysis of a negotiator at the table.

One of the objectives in doing such an analysis is to identify de facto allies at the table. De facto alliances emerge beyond the negotiation table. They may not be alliances in the context of the negotiation, instead influencing the negotiation indirectly. An executive in one of the programs told us an interesting anecdote. He was going to take part in a negotiation at which a bank and a country’s government were going to be represented. On the day of the negotiation, the executive negotiator was surprised to see that the government negotiator was an old classmate of his and they had even gone on vacation together during their university years. Due to work, the negotiator had left the country and lost touch with many of his old friends. However, seeing an old friend reminded him of the great times they had had together, and this created a different dynamic in the negotiation. Quite often, such de facto alliances escape our analysis, and they can turn out to be counterproductive even when we try our best to build an alliance.

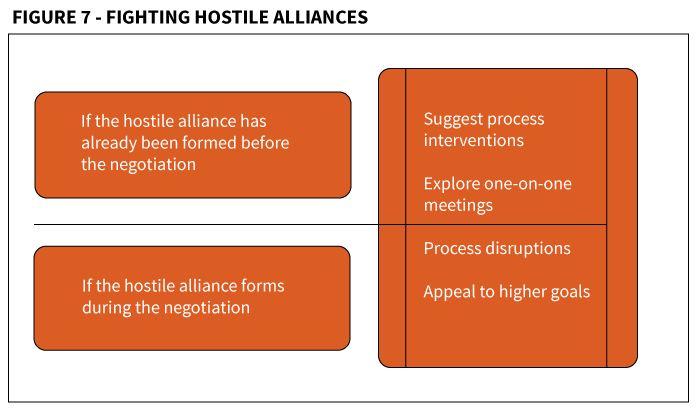

Fighting Hostile Alliances

Another important duty of a negotiator is to fight any hostile alliances. It is very important for the negotiator to attempt to prevent any hostile alliance from forming during a negotiation and to be ready to fight any such alliance that does form. Hostile alliances can be fought in two ways.

If the hostile alliance has been formed already, then it is important for the negotiator to somehow make it less relevant for the negotiation or to negate its impact. One way in which this can be done is by setting the agenda of the negotiation in such a manner that the hostile alliance is rendered less relevant or everyone is given an equal opportunity. An alternative is to see to it that the hostile alliance is broken up before the negotiation itself. This can be done by organising personal meetings with some or all of those in the hostile alliance. Generally, such one-on-one meetings are helpful for understanding different alliance partners, and they give the negotiator more flexibility to fight the alliance. If the hostile alliance is built during the negotiation process, then it is important to disrupt the process. The process of negotiation can be disrupted by raising issues that are not so important or by demanding that attention be paid to issues that can shift the other negotiators’ focus. Another way of distracting the others is by setting out goals that stretch beyond what is being discussed. Appealing to a higher morality or a higher-level goal can also help break a hostile alliance.

In the end, if we go back to the entire discussion on building an alliance or fighting a hostile alliance, one common factor that emerges clearly is that of control over the negotiation process. In general, in a multiparty and multi-issue negotiation setting, it is very important to control the negotiation process. One of the surest ways of controlling the negotiation process is to prepare and design the process before the negotiation. After all, negotiation is a skill and, as with any skill, it is better to prepare for the execution rather than the result. In any sport, a professional athlete does not prepare for the result but for the game.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Guido Stein is Academic Director of the Executive MBA of Madrid, Professor at IESE Business School in the Department of Managing People in Organisations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance).

Guido Stein is Academic Director of the Executive MBA of Madrid, Professor at IESE Business School in the Department of Managing People in Organisations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance).

Kandarp Mehta is a PhD from IESE Business School, Barcelona. He has been with the Entrepreneurship Department at IESE since October 2009. His research has focussed on creativity in organisations and negotiations. He frequently works as consultant with startups on issues related to Innovation and Creativity.

Kandarp Mehta is a PhD from IESE Business School, Barcelona. He has been with the Entrepreneurship Department at IESE since October 2009. His research has focussed on creativity in organisations and negotiations. He frequently works as consultant with startups on issues related to Innovation and Creativity.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)