By Adrian Furnham

We might not care to admit it, but most of us have a dark side. Although it’s tempting to view that as an unreservedly bad thing, as Adrian Furnham points out, it could be that our demons are just what make us the ideal candidate for a given job.

Vocational guidance, a bit of a neglected backwater in psychology, has been described as finding the ideal fit between the person (job seeker) and the job (occupation). The idea is to make an assessment of an individual’s abilities, personality, and motivation (values) and, on the basis of that profile, suggest a number of different jobs / occupations that may suit. The desired outcome is about optimal fit.

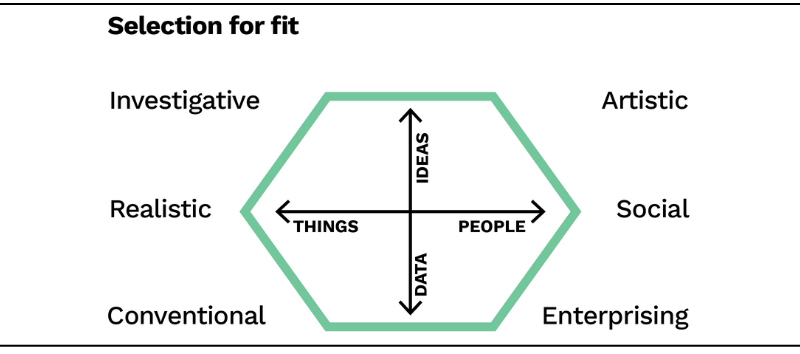

There are some simple models. So, you may ask people two straightforward questions about the types of jobs they like. Do you like most to work with people (individuals / teams) or things (technology / machines)? Are you most interested in ideas (theories / concepts) or data (numbers / facts / figures)? This creates four simple quadrants: the “things-data” group would be attracted to technical and engineering-type jobs and the “ideas-people” group would be attracted to and successful in artistic endeavours and therapy roles.

There is, however, one dominant theory in the area, developed by John Holland almost 50 years ago. He suggested that individuals’ interest patterns can be best described in terms of their resemblance to six major interest types: realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional. The realistic type has a preference for technical or outdoor activities and occupations, involving the use of equipment / technology and requiring mostly manual skills. The investigative type is interested in thinking and research activities and enjoys theory-building and abstract problem-solving. The artistic type enjoys creating and developing new things that have beauty and a desirable design. The social type enjoys interacting with people, in jobs involving educating, training, caring, and nursing activities. The enterprising type prefers action and doing, expressed in jobs that involve implementing, organizing, and leading. The conventional type enjoys activities concerned with the correct application of rules and standards; think accountant or quality controller.

Individuals’ interest patterns can be best described in terms of six major interest types: realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional.

These six types are best represented in a circular hexagonal structure, also called the RIASEC calculus. Both people and jobs can be described in the same terminology. Moreover, the Euclidian distance between the types is an indication of fit. It’s best to have an “R” person in an “R” job but the worst fit is where they are opposites (A and C, I and E). An individual’s interest pattern is described using a three-letter code reflecting the individual’s primary, secondary, and tertiary interest fields. There are all sorts of measurement issues, but suffice it to say there is good evidence for the theory and a mountain of research behind it. But a major problem for the theory and vocational guidance in general is the rapid changes in the nature of work. For instance, where would all the modern IT jobs appear in the structure? As we have seen, the new world of work has eliminated and created jobs and changed others. AI has accelerated this, presenting unique problems for “job-people fitters”.

Problematic People

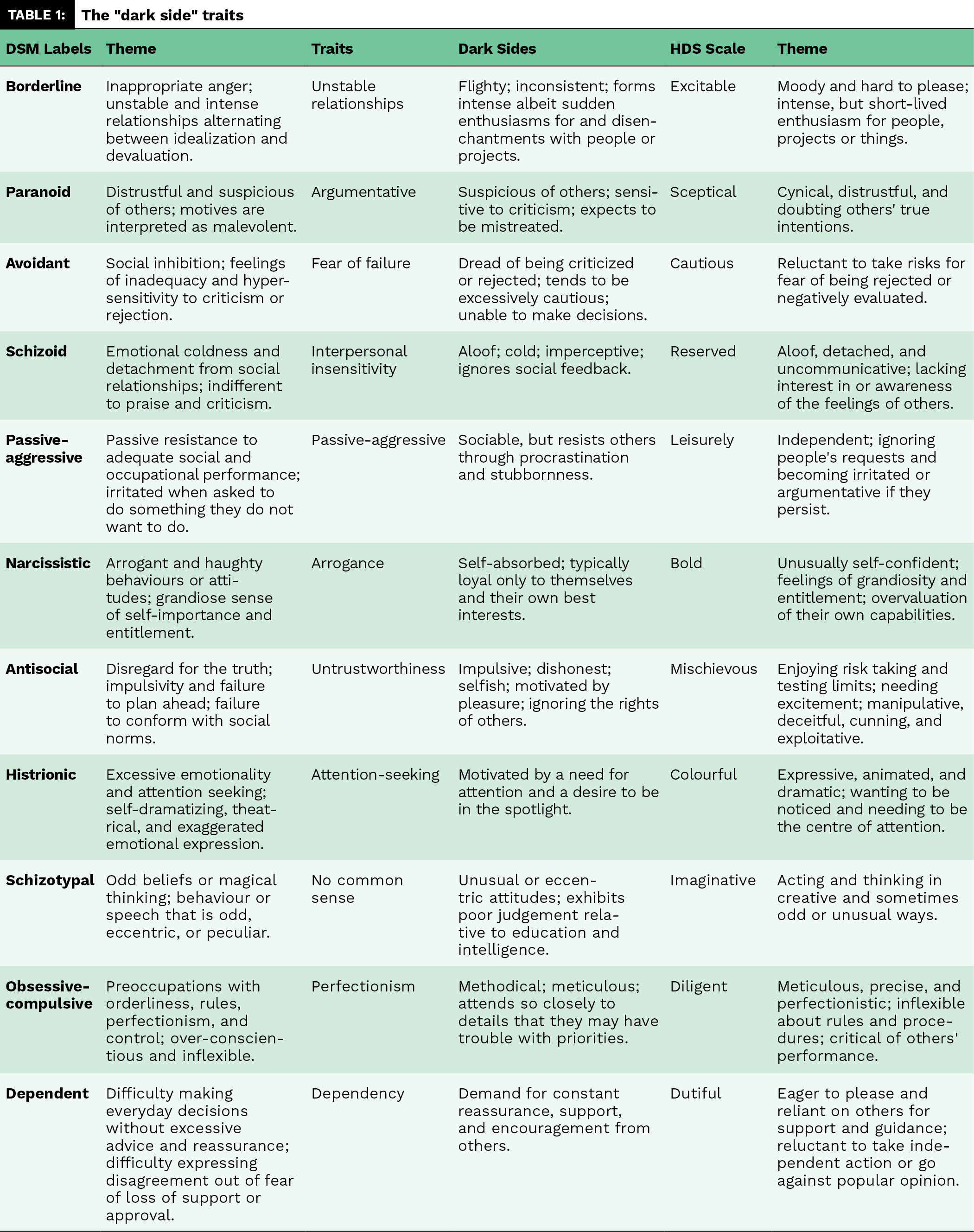

What about problematic or “dark-side” people? Are there jobs suited to them? Over the past 20 years, there has been huge interest in the dark side of personality. For many, these are essentially sub-clinical personality disorders. Although both disputed and prone to regular revision, the list below is still used. “DSM” stands for the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which classifies the personality disorders.

Robert Hogan, world expert on personality assessment, has developed his own Hogan Development Survey (HDS), which seeks to assess a person’s dark side. It is important to acknowledge that these dysfunctional dispositions emerge when people encounter stress or stop considering how their actions affect others. Over time, these dispositions may become associated with a person’s reputation and can impede job performance and career success. The HDS is not a medical or clinical assessment instrument but assesses self-defeating expressions of normal personality.

Table 1 describes these, hopefully in non-technical language.

A few important observations. First, we (nearly) all have a dark side; indeed, some people have many. Next, it is a matter of degree. It is not categorical or binary; you are not one thing over another. Third, the dark-side features may not always be a handicap. Indeed there may be jobs where a good pinch of dark-side behaviours and preferences could be beneficial. That is where vocational guidance comes back in. So, what advice to give job hunters with knowledge of their dark profile? I have done some research that explores this question.

Two Studies

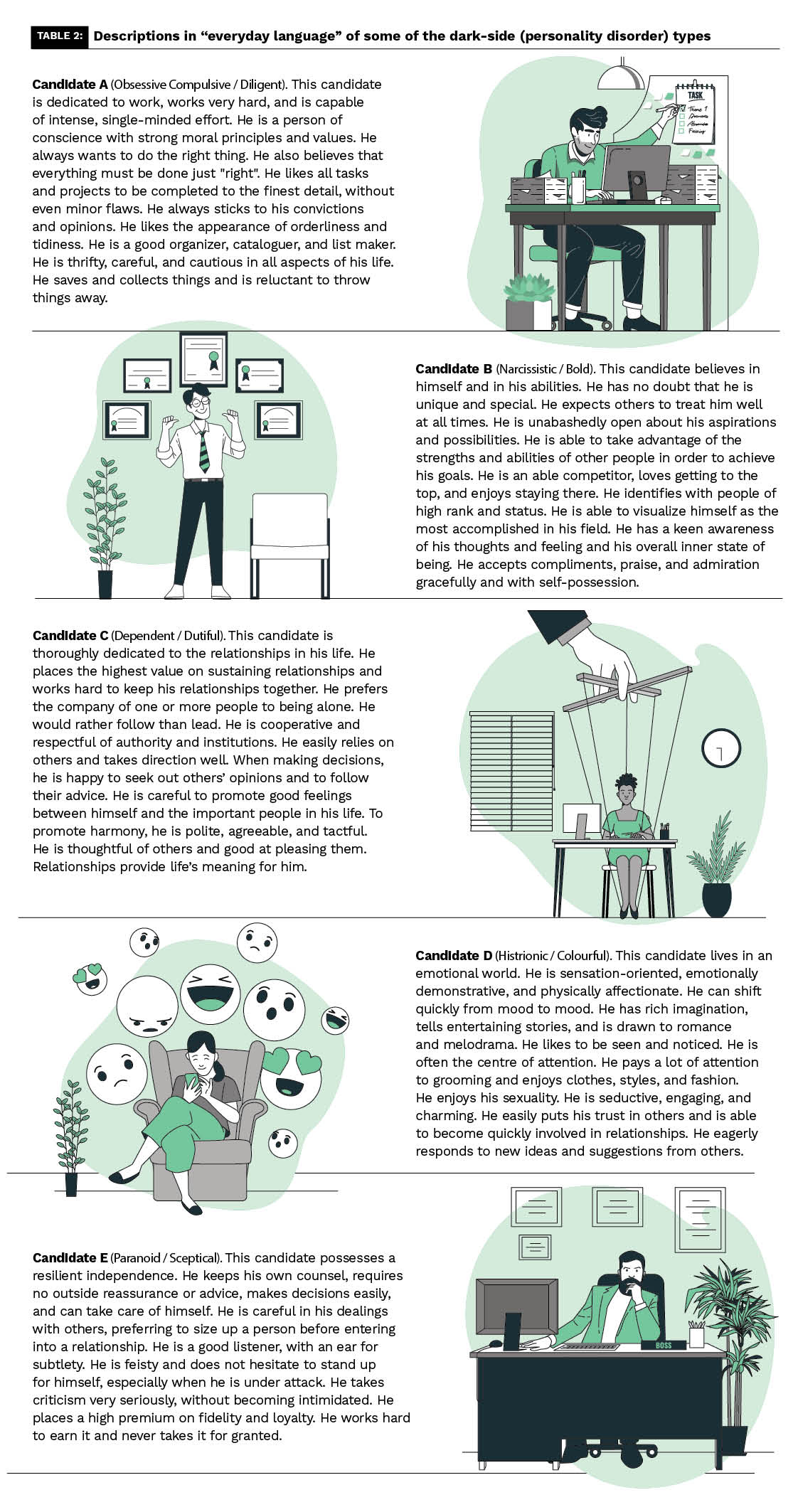

A few years ago, I conducted some studies on what can be called “the dark fit”. I was interested in what ordinary people thought were “good / ideal / fitting jobs” for those with specific dark sides. It was quite simple. I gave people “rich descriptions” of an individual based on the psychiatric literature (see table 2). One study used 11, another 10. These are examples of the descriptions. They were all males.

In our studies, our primary question was, “What sort of job do you think he will be particularly good at?” But we also asked, “Do you think he will make a good manager at work?” “Do you think you would like to work for him?” “Do you think he will have a very successful work career?” “In general, how happy do you think he is?” “In general, how successful at his work do you think he is?” “How satisfying do you think his personal relationships are?”

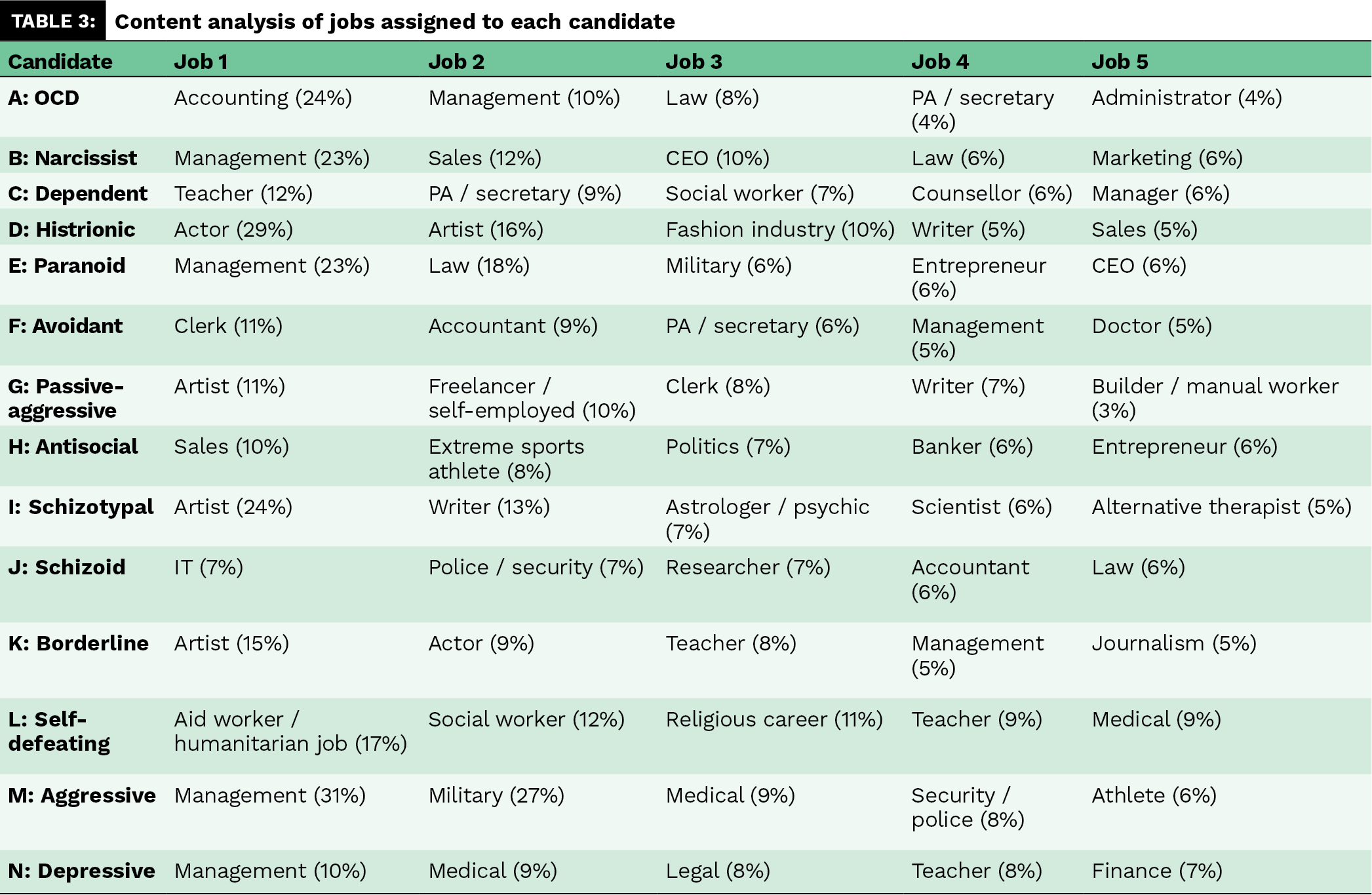

In Study I, we interviewed 230 people with an average age of 35 years. The results of the study are in table 3. The first task was to suggest a job that may suit each individual – one in which he would thrive and be both happy and successful. A “content analysis” then put their ideas / suggestions into similar categories.

We (nearly) all have a dark side; indeed, some people have many.

It was interesting that they thought that narcissists would do well in management, and psychopaths (anti-social) in sales. And there was a tendency for people to believe those with obsessive-compulsive disorder to be suited to accountancy, narcissism and paranoia to general management, histrionic to being an actor, and schizotypal to be an artist. Surprisingly, paranoid and sadistic people were judged to be the best managers, and histrionic, passive aggressive, and schizotypal the worst.

Our participants correctly identify subclinical schizoid people as “cold fish”, unwilling or unable to establish and maintain close relationships. They also correctly identified others with similar problems, particularly the depressive, avoidant, and schizotypal types. One of the more obvious and debilitating characteristics of the clinical schizoid condition is the interpretation and display of emotion.

An expert with a full understanding of the dark-side features would be impressed by what these lay people came up with.

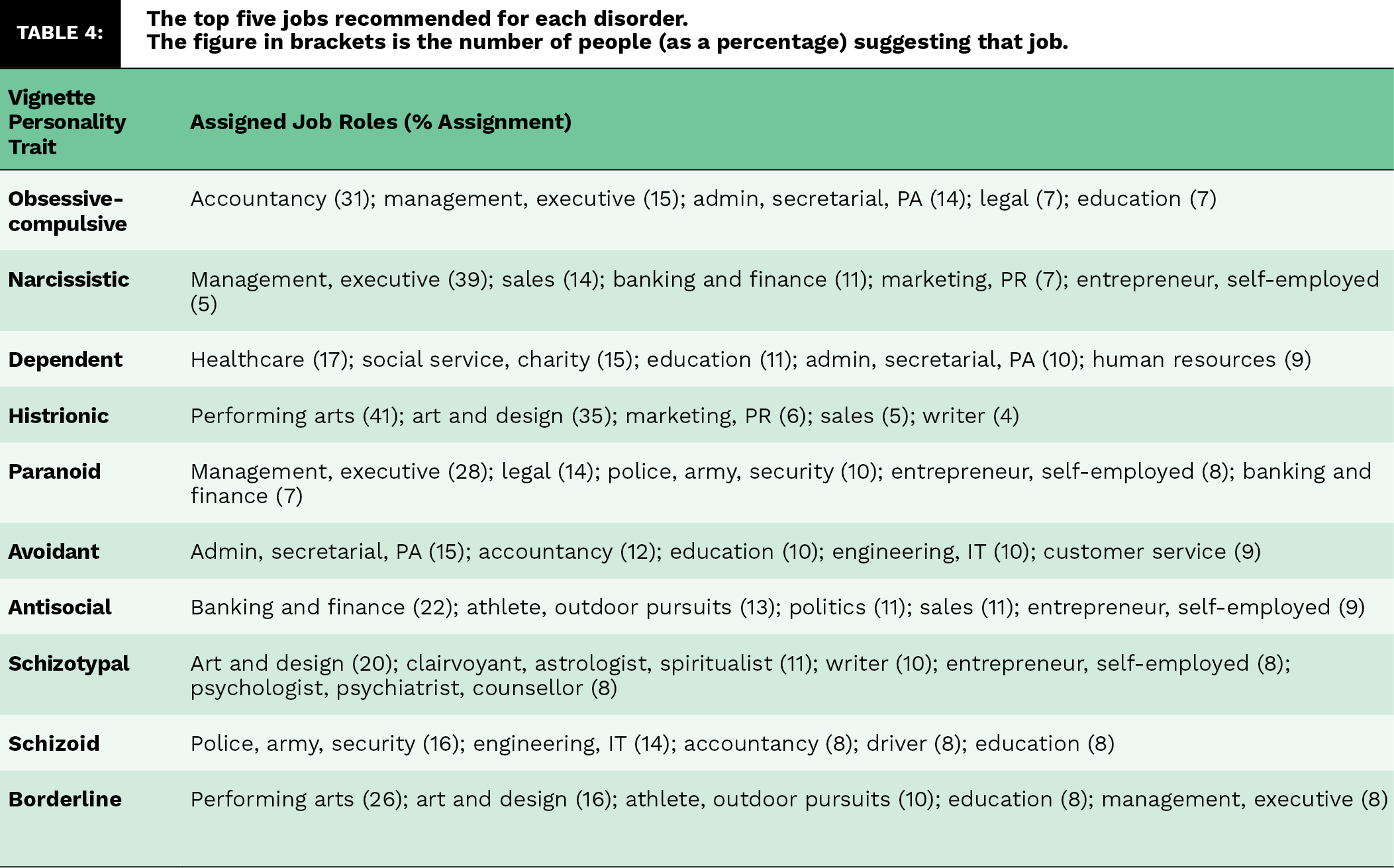

In the second study, respondents were 92 people with an average age of 37. The results are in table 4 and essentially confirm the first study. It was particularly amusing to see that they thought psychopaths (anti-social) would do well in banking and finance, and narcissists as management executives.

The results of the two studies are broadly compatible. And what they show is insightful, frightening, and amusing. What job did they think a psychopath was possibly suited to? Banking, sales, and politics, where perhaps swagger and a light conscience might suit them well. Narcissists were also thought of as suited to management and sales.

There are a number of interesting conclusions:

First, ordinary people are pretty good at vocational guidance. They obviously understand the concept of fit. There are jobs which suit all types, but people pick up some of the distinctive characteristics of the “dark-side” personality. Of course, there are stereotypes involved here and there can be many different “varieties” of every job. Thus, for “management” it depends on the size, purpose, and history of the institution.

Second, there seem to be plenty of (reasonable) job possibilities, even for the “darkest of the dark side” people. The quiet, solitary, low-EQ person quite uninterested in people can thrive in IT jobs, although they may not be ideal managers of others. The self-confidence of narcissists can make them be, or at least appear to be, ideal for lots of executive roles. Histrionics absolutely thrive under the spotlights on stage.

Third, light and dark-side personality tells us about choice and preference and, to some extent, about motivation. But vocational guidance also requires an assessment of ability. Some jobs are simply more glamorous than others; they are higher-profile and better paid. But they require particular skills. Fit in terms of personality alone is not enough.

Caveat

It is very important to point out, however, that psychologists and psychiatrists have mostly dropped the previously held categorical scheme in favour of a dimensional approach to diagnosis. That is, they reject the diagnosis / claim that a person either is or is not a psychopath / narcissist, etc. We are on a dimension (like height) from not at all to very psychopathic. Essentially, the dark side is not binary, as in you are or you are not. There are shades of grey. And, like all dimensions (think height or IQ), the more extreme you are, the more certain particular problems arise.

This means that people with quite a lot of darkness in a certain area can thrive in an environment that requires it. Rejoice that your accountant is a touch diligent, your top designer a tad imaginative, and your favourite actor histrionic. Again, those with a very high (dark) score on any dimension might easily self-destruct. It’s like intelligence; you need to be bright enough to do well, yet extra “fire power” adds little.

Also, many people are co-morbid, meaning that they have more than one dark side at the same time. Indeed, the dark-sides do cluster. The psychiatric manuals place all these dark-side people into three categories: (a) odd and eccentric: paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal; (b) dramatic, emotional, and erratic: antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic; (c) anxious and fearful: avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive. Another schema for doing this is based on the idea of managing interpersonal anxiety: moving away (i.e., detaching and withdrawing from others), moving against (i.e., influencing and charming others), and moving towards (i.e., obeying and getting close to others). Often, it’s the “moving against” cluster that sees the most successful and highest-profile business people having a good fit of “personality”.

Finally, and most crucially, good-fit personality is necessary but not sufficient for success in all jobs. You also need talent. The “wannabe” theatrical borderline or schizotypal person will only succeed in theatre, the arts, and the creative industries if they actually have talent. And for this there is no substitute.

About the Author

Adrian Furnham is in the Department of Leadership and Organisational Behaviour at the Norwegian Business School. His scores on “histrionic” are elevated, but he thinks he is in the right job.

Adrian Furnham is in the Department of Leadership and Organisational Behaviour at the Norwegian Business School. His scores on “histrionic” are elevated, but he thinks he is in the right job.

References

-

Dotlich, D. & Cairo, P. (2003). Why CEOs Fail. New York: Jossey Bass.

-

Furnham, A. (2016). Backstabbers and Bullies: How to Cope with the Dark-Side of people at Work. London: Bloomsbury

-

Furnham, A. (2023). “Have you ever met a psychopath? The anatomy of the corporate psychopath”, European Business Review,

-

Furnham, A., & Petropoulou, K. (2019). “Mental health literacy, sub-clinical personality disorders and job fit”, Journal of Mental Health, 28, 249-54.

-

Furnham, A., Abajian, N., & McClelland, A. (2011). “Psychiatric literacy and personality disorders”, Psychiatric Research, 189, 110-14.

-

Hogan, R. (2007). Personality and the fate of organizations. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

-

Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (1997). Hogan Development Survey Manual. Tulsa: HAS.

-

Harrison, S., Grover, S., & Furnham, A. (2018). “The perception of sub-clinical personality disorders by employers, employees and co-workers”, Psychiatry Research, 270, 1082-91.