By Ayna Isazade, Supervised by Dr. Anna Rostomyan

Emotional labor has become an important concept in the healthcare sector (Dogan et al., 2022). Controlling one’s emotions and expressions to conform to the standards of behavior adopted by an organization is called emotional labor (Yolanda, 2023). Emotional management refers to internal strategies to regulate emotions effectively (Chu, 2023). Healthcare professionals spend more emotional labor than other fields (Guzel et al., 2024). This study examined emotional labor and emotional management among healthcare professionals using a quantitative survey design with 50 participants. My findings emphasize that emotional management difficulties are not inherently gendered, suggesting that support systems should not be based on gender stereotypes but instead address the emotional challenges faced by healthcare professionals universally. This study contributes valuable insights into the emotional labor and emotional management experiences of healthcare professionals.

Literature Review

Emotional labor is the regulation of employees’ emotions and expressions to meet interpersonal role expectations at work (Li et al., 2024). Emotional labor has been defined as the personal emotional management of individuals that enables them to create an appropriate facial expression or physical movement that can be observed by society (Chu, 2024). According to Hochschild (1983), there are three types of emotional labor, which are surface acting, deep acting and genuine acting.

Genuine acting is a process where the emotions felt are the same as the emotions displayed. Employees are motivated by intrinsic rewards rather than extrinsic rewards. Genuine acting employees spend minimal mental effort when they enjoy their work and display the emotions they truly feel, and this requires less effort from the employee compared to surface or deep acting (Chiwa & Wissink , 2022).

Surface acting is when employees express their emotions by changing their physical behavior or facial expressions that do not reflect their true feelings or shape their inner emotions.

An example of this would be faking or hiding emotions. Surface acting deals with emotions passively and expresses them internally, not just on the surface (Feng et al., 2024).

Deep acting attempts to bring internal and external emotions into line with norms. Deep acting practitioners create the excitement that is needed or expected (Sarraf, 2018).

Emotional management and emotional labor are deeply connected, as they involve regulating and aligning emotions to meet professional and organizational goals. The effort employees expend to control their emotional expressions during interactions with customers is known as emotional labor. However, emotional management encompasses a broader set of skills and approaches used to effectively manage emotions, both internally and externally (Chu, 2023).

Employees who engage in emotional labor are more likely to experience emotional tiredness, particularly when their workload surpasses their emotional capacity, which can result in occupational burnout. Employees may experience job burnout and poor job performance if they have negative emotions or are unable to logically regulate them and there is no help or strategy accessible to address emotional issues. Employees who experience emotional exhaustion will feel emotionally detached, have negative emotions including tension, worry, despair, and anger, and their physical and emotional vitality is depleted. Additionally, they will express discontent with their jobs and risk losing them (Chien et al., 2022).

Continuous surface acting by employees or expectations of such behavior by organizations can have detrimental consequences because people can be good at manipulating their emotions for short periods of time. However, this has been difficult to maintain for many years. Organizations should prioritize balance between surface action expectations. An employee may feel good because a deeper experience of the necessary emotions can produce a state of mind that makes them feel that way (Kilicarslan & Ozsoy, 2024).

According to Chiwa and Wissink (2022) the most stressful type of emotional labor for employees was surface acting. The study found that the effects of surface acting on employees included emotional exhaustion, anxiety, anger, fatigue, low self-esteem, poor performance, at work, feelings of resentment, conflict of beliefs, mood swings, and feelings of being dishonest with oneself.

At work, emotional labor has a big impact on organisationally desired outcomes. Additionally, it impacts job satisfaction, physical and mental health, individual and organizational outcomes, customer service quality, customer satisfaction, and performance. Compared to those who frequently engage in surface acting, employees who display genuine emotions at work report higher levels of intrinsic job satisfaction. Deep acting promotes personal integrity, achievement, and a feeling of accomplishment (Sarraf, 2018).

Living emotions is very crucial for nurses to work through the clinical moral burdens and also enables them to have ethical and meaningful contact with distressed people. A positive relationship was revealed between nursing students’ caring behaviors and emotional labor behaviors (Dogan, Gumus, Kacmaz, 2022). More than half of nurses reported experiencing empathic emotions such as sympathy, sadness, compassion, and grief. Emotional labor can affect nurses’ physical and mental health, reduce nurses’ job engagement, and increase burnout, contributing to intentions to leave work (Chien , Lan, Chiou & Lin, 2022).

Many studies have yielded different results depending on genetic differences. Ericson (2001) found no significant differences between genders in emotional labor, Gender has no effect on the management of positive or other negative emotions. According to study female emergency medical services professionals were not found to have significantly lower surface acting and deepacting or higher job satisfaction than male EMS professionals (Balu al., 2014). However, Cheung and Tang (2011) explored how genders show different emotional labor behaviors. Findings indicated that women are more likely to engage in deep acting, while men rely more on surface acting. According to Goubet and Chrysikou (2019), women try more emotional management strategies to regulate emotions.

Findings

This study aims to address the following questions.

- Are there significant gender differences in emotional labor in the workplace?

- Do men and women differ in their emotional management styles? (healthy vs. unhealthy)?

The study employed a quantitative research design using survey data to assess emotional labor experiences and emotional management among healthcare professionals. Emotional management was evaluated through a Likert scale (1-5) questionnaire. The research included 50 participants—25 men and 25 women working in the health sector. Convenience and snowball sampling were used to recruit participants. Data collection was made by using the Likert scale questions measuring emotional labor and emotional management styles.

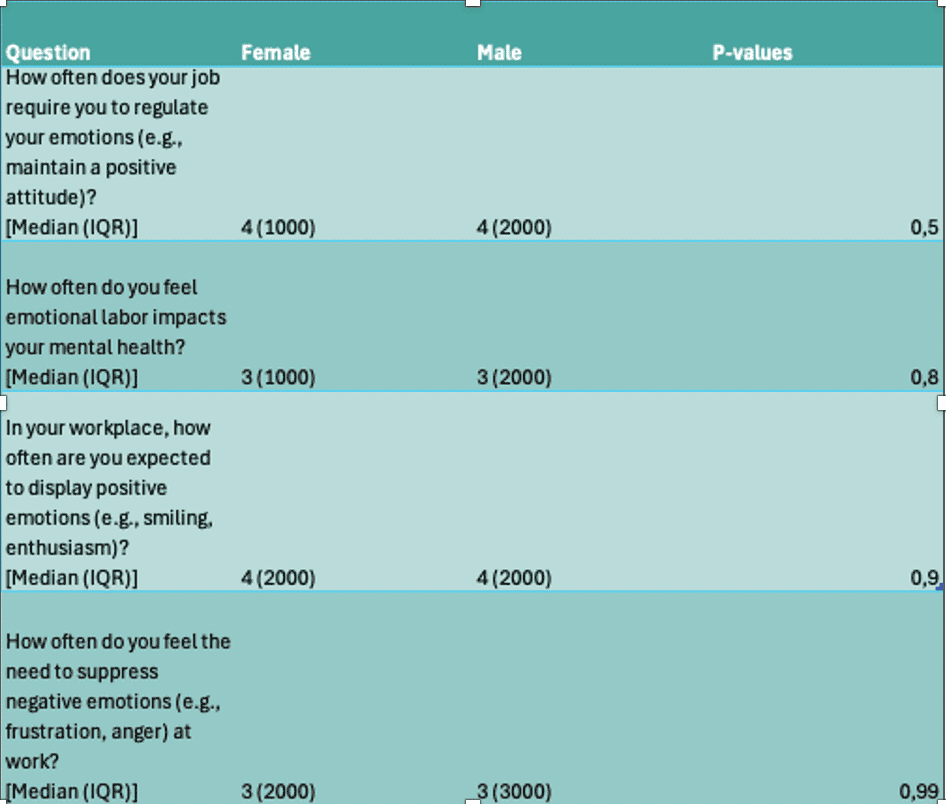

Table 1: Gender Comparison of Median Emotional Management Scores

The Mann-Whitney U Test was conducted for the statistical comparison of the median scores of emotional management for men and women. Median scores for both genders ranged between 3 and 4, with no statistically significant difference observed. The p-values showed no significant statistical difference between genders. This may imply that gender is perhaps not a determining factor in emotional management scores.

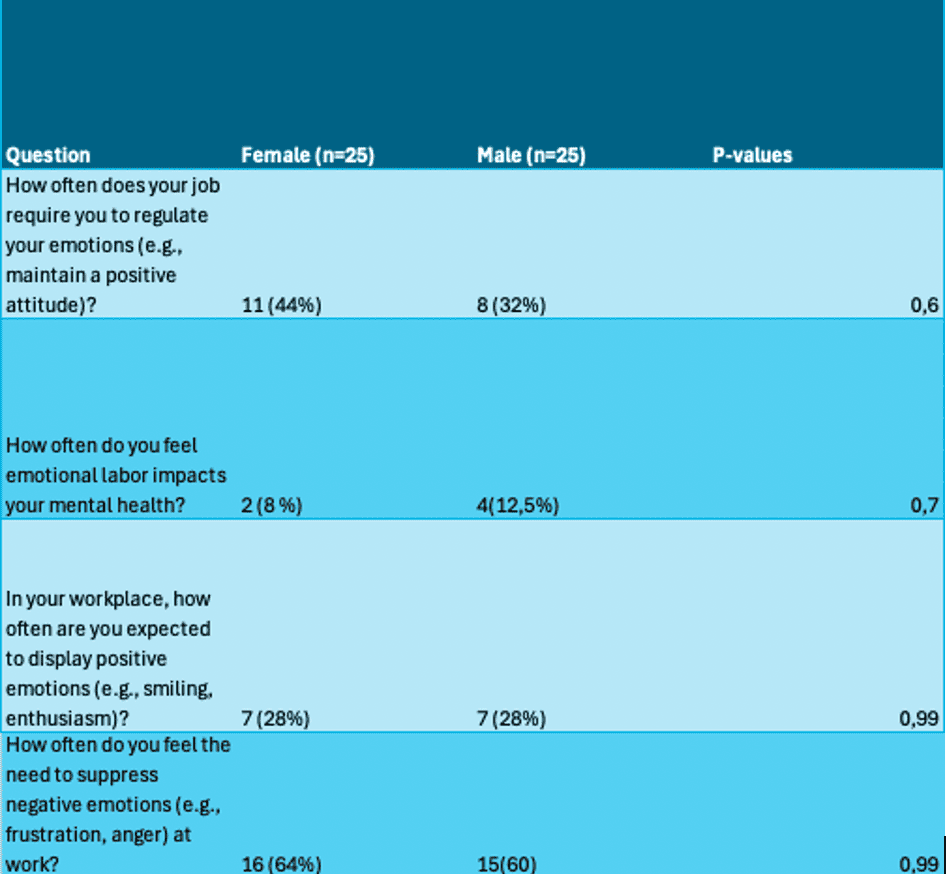

Table 2: Gender Comparison of Healthy and Unhealthy Emotional Management Classifications

`Based on their responses, participants were classified as ‘healthy emotional management’ or ‘unhealthy emotional management, represented by 1 and 0, respectively. It showed that the men and women had unhealthy styles of emotional management. No statistically significant difference between the groups was found. Accordingly, as it befits, initial median comparisons had already suggested no differences; hence, statistical testing of the emotional management scores or styles did not reveal any significant differences by gender. Males and females both reported equal difficulties in maintaining healthy emotional management, emphasizing that such difficulties are not inherently gendered.

Conclusion

The findings of this study have shown that emotional labor and emotional management difficulties in healthcare professionals are not affected much by gender. Most of the male and female participants indicated difficulties in healthy emotional management, hence being a challenge across the healthcare sector. This, therefore, calls for addressing emotional labor and emotional management in a manner that does not lean on gender but focuses on the emotional burdens faced by all health professionals. Support systems and interventions should be structured to assist professionals in managing their emotions effectively, irrespective of gender, toward better well-being and job performance.

References

-

Balu. G., Bentley, M. A., Eggerichs, J., Chapman, S., & Viswanathan, K. S. (2014). Are there differences between male and female EMS professionals on emotional labor and job satisfaction? Journal of Behavioral Health, 3(2), 82-86.

-

Cheung , F., & Tang, S. K. (2010). Effects of Age, Gender and Emotional Labor Strategies on Job Outcomes: Moderated Mediation Analysis. Applied Psychology: Healthy and Well-Being, 2 (3), 323-339.

-

Chien C.C., Lan, Y. L., Chiou, S. L., & Lin, Y. C. (2022). The Effect of Emotional Labor on the Physical and Mental Health of Health Professionals: Emotional Exhaustion Has a Mediating Effect. Healthcare, 11(1).

-

Chiwawa, N., Ngcobo, N. F., & W, H. (2022). Emotional labor: The effects of genuine acting on employee performance in the service industry. Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(2).

-

Chu, H., & Chu, J. (2023). Emotional Labor Strategies for Frontline Social Workers Balancing Authenticity and Occupational Expectations. Academic Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 24 (6), 134-137.

-

Chu, L. C. (2024). Effect of compassion fatigue on emotional labor in female nurses: The moderating effect of self-compassion. PLOS One, 19 (3), 1-19.

-

Dogan, N., Gumus, K., & Kacmaz, H. Y. (2022). The Emotional Labor and Caring Behaviors of Nursing Students. Acibadem Universitesi Saglik Bilimleri Dergisi, 13 (4), 655-664.

-

Ericson, R. (2001). Emotional Labor, Burnout, and Inauthenticity: Does Gender Matter?Social Psychology Quarterly, 64 (2). 146-163.

-

Feng, H., Zhang, M., Li, X., Shen, Y., & Li, X. (2024). The Level and outcomes of emotional Labor in Nurses: A Scoping Review. Journal of Nursing Management.

-

Goubet, E. K., & Chrysikou, E. G. (2019). Emotion Regulation Flexibility; Gender Differences in Context sensitivity and Repertoire. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

-

Guzel, S., Dombekci, A., Topuz, V. C., & Yesildal, M. (2024). The Relationship between Distress Tolerance, Emotional Labor and Job Satisfaction in Private Hospital Workers. JMMR, 13 (1), 59-66.

-

Hochschild, A.R. (2003). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling (20thanniversary ed.). Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

-

Kilicarslan, K., & Ozsoy, E. (2024). Which type of emotional labor leads to burnout? KOCATEPEİİBFD, 26 (1), 101-108.

-

Sarraf, A. R. A. (2018). Relationship between Emotional labor and Intrinsic Job Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Gender. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Organizational Management, 7 (1).

-

Yolanda, A. (2023). Cultivating Organizational Commitment: The Impact of Emotional Labor and the Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Ultima Management Journal Ilmu, 15 (2), 180-197.

-

Li, L., Xu, R., Wang, S., Zhao, M., Peng, S., Peng, X., Ye, Q., Wu, C., & Wang, K. (2024). The moderating effect of family structure on the relationship between early clinical exposure and emotional labor of nursing students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 23 (1), 1-9.