You might have heard about the recent brouhaha regarding online payment processor PayPal and its planned changes to its acceptable use policy (AUP). That one or more of the Big Tech vendors would go this far over the line in terms of what was morally and ethically unacceptable, if not illegal, was not only predictable (indeed, I did so nine years ago), it was inevitable.

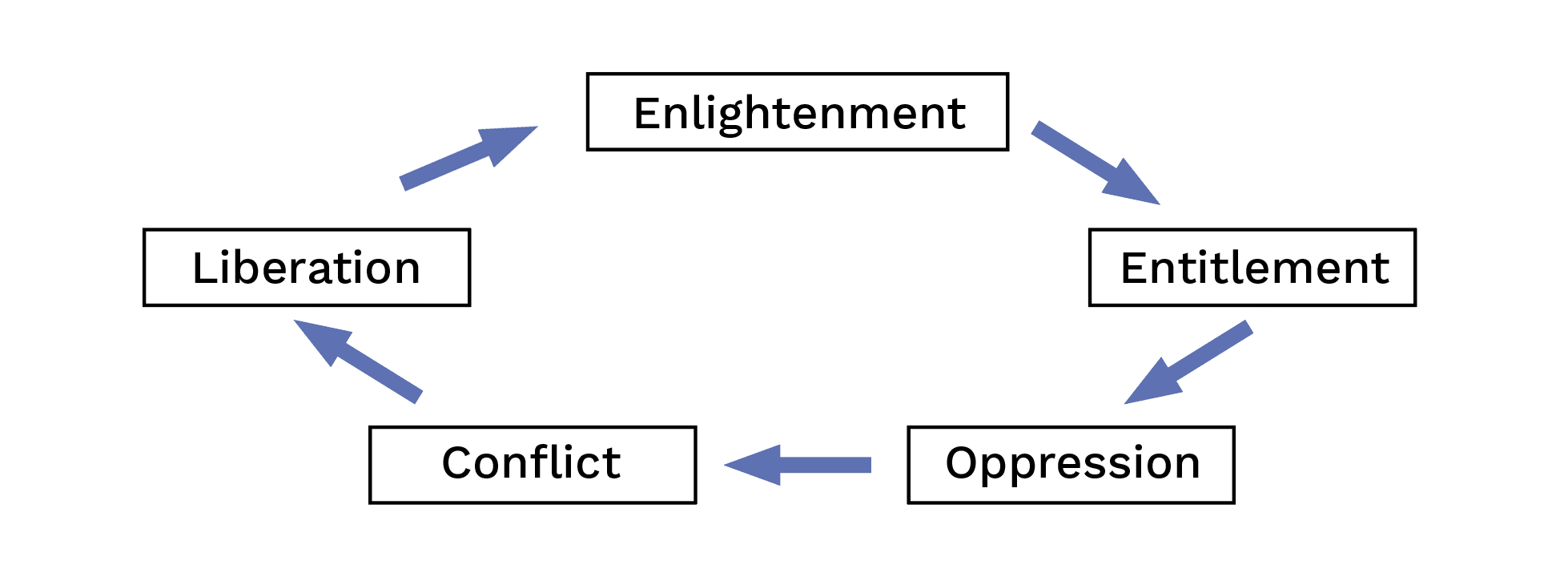

The only remaining question to ask is this: what are we, collectively, going to do about it? As always, history gives us many guides as to what we will see in the coming years, so let’s revisit the past in order to pre-visit the near future.

YinPal?

It has not gone unnoticed that technologists, business people, and bureaucrats focus on using technology to solve a problem at hand, often missing the unforeseen negative consequences of its use. Only later, after we have opened a new Pandora’s box, do we understand that the laws of the universe dictate that we never get something for nothing, and our efforts towards greater civility and humanity are always and relentlessly countered by the universal forces of entropy and chaos.

Recognition of this fact is deeply rooted in Eastern thought, and manifest in the concept of Yin and Yang. As stated in the now-current version of Wikipedia, Yin and Yang

“is a Chinese philosophical concept that describes opposite forces which are interconnected. In Chinese cosmology, the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy, organized into the cycles of yin and yang and formed into objects and lives. Yin is the receptive and yang the active principle, seen in all forms of change and difference such as the annual cycle (winter and summer), the landscape (north-facing shade and south-facing brightness), sexual coupling (female and male), the formation of both men and women as characters and sociopolitical history (disorder and order).”

To summarise for Western thinkers: Good coexists with Bad, Benefit always comes with Cost, Yin always accompanies Yang; one only exists because of the other, rather than in spite of.

Nobel Cause From Ignoble Outcomes

Upon his death in 1896, Alfred Nobel endowed several international awards which he believed would serve the greater good of humanity. Among these awards was the Nobel Peace Prize, to be awarded each year to

“those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind” .

Today, over a century later, the Nobel Peace Prize is recognised as one of the most prestigious recognitions that our society can bestow upon a person, putting them in the company of former winners such as Nelson Mandela and Frederik Willem de Klerk, Yasser Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin, Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho – the Yin and Yang of these opposed pairings being intentional.

What is of note is how Nobel funded his noble endeavour. It is a dynamite story, or rather, the story of dynamite. Nobel’s invention and exploitation of high explosives made him fabulously wealthy, and one of Europe’s foremost nineteenth-century industrialists. By harnessing the potential energy tied up in chemical compounds, Nobel directly accelerated the creation of our modern society. Every facet of modern living has been enabled by Nobel’s dynamite, for which he was handsomely rewarded at the time.

However, not all of this story is sweetness and light. I have written extensively about the intertwined promise and peril of technology. Technology has no morality; it just is. How we use a technology determines whether it is moral or immoral, good or bad, Jedi or Sith, and therein lies the rub.

Nobel’s invention enabled exponential growth in the health, wealth, and well-being of mankind, while simultaneously causing near limitless death and despair. High explosives enabled and then accelerated both the industrialisation of society and the industrialisation of warfare. His inventions are causally linked to hundreds of millions of improved lives, as well as the over one hundred million deaths realised in our two World Wars. For all of the positive, productive uses we found for his high explosives, we found as many ways to use them for destruction and death, if not more.

Late in his life, Nobel bore some regret that he had opened this Pandora’s box which could not be resealed. The best he could do thereafter was to take actions that might identify and mitigate the negative effects of his creation. Alfred had learned that to embrace the Yang of the universe, one must also accept and deal with its Yin.

Everything Changes, But Us

While we human beings like to think of ourselves as very dynamic, evolving, and flexible, at timescales longer than one or two lifetimes, our humanity tends to change very little. This is an evolutionary necessity, as long as our world changes at geologic, rather than human, timescales. As a result, things change in our society far less readily than we often like to believe.

“Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

Winston Churchill may have been channelling Spanish philosopher George Santayana when he supposedly said this before the House of Commons in 1948. There remains debate as to the authenticity of this quote, but its inherent truth survives such scrutiny.

If we examine any significant technology that humanity has developed since our inception, we can identify both its good and bad impacts. Splitting the atom can on one hand produce near limitless power to support a civilisation, and on the other hand destroy that civilisation in mere seconds. A bridge that on one hand connects two peoples can, on the other, allow one of those peoples to subjugate the other. Domesticating flora and fauna allowed our population to explode, but also made us deeply dependent upon nature’s continued obedience to our will. The fossil fuels that made us more civilised, wealthy, and healthy than could have been imagined in Nobel’s time now threaten our existence.

Crimea: School of Humanities

“Theirs Not to Make Reply, Not to Reason Why. Theirs But to Do and Die.”

Lord Alfred Tennyson wrote The Charge of the Light Brigade to honour those brave soldiers in the Crimean War of the 1850s. Their charge was doomed to failure from the start, in large part due to the convergence of eighteenth-century cavalry tactics with nineteenth-century technologies; Yin meets Yang. Fast forward one hundred and seventy years and we once again find ourselves in Crimea facing the convergence of tactics and technology, construction and destruction, Yin and Yang.

Today as I write this, within an hour’s flight from where the light brigade met their doom, continental Europe’s largest bridge lies dynamited into partial ruins. Europe’s largest nuclear power plant is under similar threat of Nobelian destruction. Elsewhere, a significant portion of the continent’s food stocks are under attack by high explosives, tank tracks, and nitrogen quotas, while its petrochemical lifeline has been partially severed, again with dynamite.

We simultaneously live at the apex of nearly a century of peace and prosperity and a time where all of this civility could be destroyed with a single mouse-click. We find ourselves surrounded by comfort, convenience, and connectivity, perhaps without recognising that we may also be prisoners to our dependence thereon. Many of us live in fear of the unknown that these crises lay at our feet. But, we should not be surprised by either the fact that there would be a price to pay for making these decisions, or that their costs might be proportional to the gains we have enjoyed over the last century.

The Future at Risk

While Churchill’s prior quote may be disputed, others are beyond dispute. In his “Finest Hour” speech from 18 June 1940, Churchill stated,

“If we open a quarrel between the past and the present we shall find that we have lost the future.”

Across the board, our present society seems to be battling its past. Part of this is simply the process of innovation. Technology always brings some degree of disruption, otherwise why use it?

However, some technologies present such dramatic degrees of disruption that they necessarily change our society, our polity, even our morality. While we embrace the Yang of these technologies with aplomb, we must be mindful of their inevitable Yin. We cannot enjoy the benefits of such disruptive technologies as plant and animal husbandry, dynamite, steel, fossil fuels, or nuclear energy without having to protect against their hidden costs.

Each of these technologies has brought with it enormous unintended consequences, the costs of which are only now coming due. Their bill is intimidating, and will be paid over many generations to follow.

While many may not have recognised it, big data, social media, and mobility are equally disruptive technologies. Their power transcends the limits of the Capital Age created by oil, steel, and electricity and they have thrust us into the Information Age.

Data Crush

In 2013, I wrote and published my first book, Data Crush. In Crush, I discussed many of the benefits that technologists expected to derive from the combination of big data, social media, and mobility. These technologies were still relatively young but it was clear that they were producing massive social, economic, and political changes to our world, largely for the good. The companies who led the charge with these tools generated trillions of euros of economic value and changed how our entire society operated. In Data Crush I attempted to provide a roadmap for organisations to get on the bandwagon of these technologies as quickly as possible, so as to harvest their benefits.

By the time I wrote my second book, Jerk, in 2015, the dark side of these technologies had already started to reveal itself. The Yin had rejoined the Yang and it was clear that these three technologies were going to bring with them an exceptionally high cost to our world. Charge forward to 2022, and it is now abundantly clear that those trillions of euros of value collected by Big Tech brought with them enormous costs which are now coming due.

Your Continued Use Constitutes Your Acceptance?

Big Tech has created a gigantic shift in the social, economic, and political environment of our world, not all of it for the better. As I write this article in the midst of the rest of this day’s chaos in Europe, another example of technology’s Faustian bargain exploded on social media, the very platform that helped to create it.

As I write this paper, it was just revealed that Big Tech financial giant PayPal announced plans to change its “acceptable use policy” (AUP) as of 3 November 2022 to include new terms that should be considered troubling, to say the least. In this policy change, PayPal reserved the right to remove from any user’s account US$2,500 for any and each instance of a user spreading “misinformation”. PayPal did not explain its definition of “misinformation”, but it did state that this definition was “…at its sole discretion”.

Such language from an individual corporation is both stunning and chilling, and represents the sort of meta-sovereignty that would be the Yin to the vast wealth and power accumulated through the Yang of Big Tech. This revelation created a firestorm across the very social media platforms that incubated it – unintended consequences indeed.

It appears that PayPal has walked back its plans, they themselves promoting “misinformation” by claiming that their own disclosure wasn’t disclosed. PayPal did not apologise for making this very public change to their policies. Rather, they denied ever having done so. Subsequently, they changed their story to claim that they did so “in error”. That’s apparently at least US$5,000 that they owe each of their customers, if turnabout is fair play.

The widespread, vocal, and passionate public backlash is apparently nothing but further evidence of the dangerous “misinformation” that PayPal claims that they are trying to prevent. We are to believe that this is all apparently a misunderstanding at best, or a nefarious plot that PayPal was trying to prevent at worst. There was no apology, no admission of guilt, certainly no remorse.

Where Have I Met You Before?

This event calls to mind another quote from Winston Churchill from similar events in his lifetime:

“What I find unendurable is the sense of our… falling into the power, into the[ir] orbit and influence, and of our existence becoming dependent upon their good will or pleasure.”

What event was Churchill referring to in this quote to the House of Commons? He was responding to Germany’s annexation of the Sudetenland, in October 1938. Churchill recognised that, again, a Pandora’s box had been opened, a border literally crossed, and the unintended consequences of a Faustian bargain were coming to collect.

What does all of this mean to us? What does the future hold? If we are standing at the borders of a digital Sudetenland, what lies beyond that border? The answers to these questions from Churchill’s Capital era came after fighting a global, capital-intensive war of immense human cost. The answer in the Information era will certainly be global, information-intensive, and of immense moral cost. Beyond that, all I am certain of is that if we do not act, as a society, against this overt form of oppression, we will face what Churchill characterised in 1938 with

“a [Media] under control, in part direct but more potently indirect, with every organ of public opinion doped and chloroformed into acquiescence, we shall be conducted along further stages of our journey.”

Big data, social media, and mobility have put at the disposal of individual humans more power than ever before in our history. It is time that we stopped handing that power over to others for them to harvest, process, and turn into their own power and wealth. It is time to take that power back, for the benefit of all, rather than the few. If we do not, Churchill predicts,

“…do not suppose that this is the end. This is only the beginning of the reckoning. This is only the first sip, the first foretaste of a bitter cup which will be proffered to us year by year unless by a supreme recovery of moral health and martial vigour, we arise again and take our stand for freedom as in the olden time.”

Everything old is new again.

This article was originally published on October 14, 2022

About the Author

Christopher Surdak is an award-winning, internationally recognised author and an expert in leading technologies such as blockchain, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, cybersecurity, and social media. He has guided organisations around the world in their digital transformation journeys, and as a Juris Doctor has contributed to regulatory and legislative efforts to keep up with our changing society.

Note: This is a topic which I have studied, contributed to, and written about for well over a decade, with varying degrees of accuracy and efficacy. My record here stands on its own merits, with fans and detractors often in equal measure.