Mired in a period of low growth, developed economies are becoming increasingly tough places to do business. Fortunately, while the overall size of markets may be stagnant or even shrinking, individual consumers are not standing still. Their behaviour change is offering a significant growth opportunity for businesses at the forefront of consumer understanding.

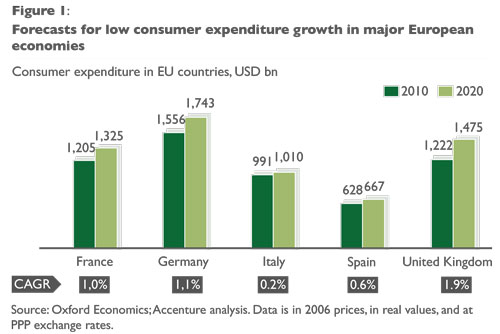

These are trying times for business leaders seeking growth in developed markets. Fewer than half the OECD economies are expected to grow by more than 1 percent in 2013. Expectations are equally dismal for consumer expenditure growth in Europe’s leading countries; especially those in Southern Europe (see Figure 1). Absolute growth in private consumption between 2010 and 2020 is now forecast to be higher in Sudan than in Italy, and higher in Chad than in Spain.

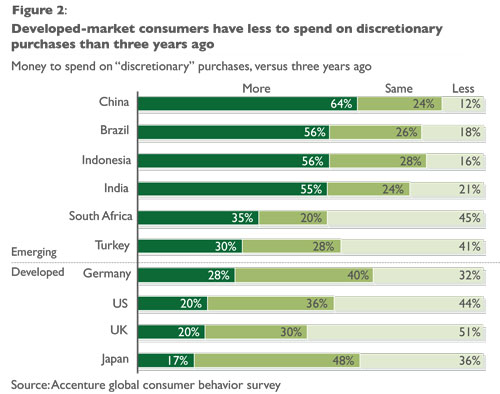

This stagnation at the level of national economies can be seen at the individual consumer level as well. As part of our study into global consumer behaviour, we surveyed 10,000 consumers from four developed and six emerging economies. Only 21 percent of developed-market consumers felt they had more money to spend on discretionary purchases than three years ago. In emerging markets, this figure was 49 percent (see Figure 2).

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

It would be no surprise, then, to find that businesses are feeling the strain under these conditions. However, our survey of 600 business leaders found that optimism abounds – in developed economies as well as emerging ones. Nearly three in four (73 percent) business leaders in developed economies were confident that their companies would achieve profitable growth in the next two to three years. Such confidence, though, is out of step with past performance: nearly half (48 percent) of the world’s 2300 largest listed companies based in developed markets failed to grow both profits and revenues in the last three years.

Where do companies think their future growth is likely to come from?

Many have turned to emerging markets. But those economies are slowing, too, and multinationals are finding these environments difficult to operate in. China’s growth is slowing as household consumption continues to lag investment. India’s 2012 growth rate was the lowest in a decade, and Brazil suffered a slowdown that saw economic growth tumble from 7.5 percent in 2010 to just 1 percent in 2012.

Several large global companies, from sports clothing retailers to consumer goods companies, have recently issued profit warnings or lowered earnings forecasts in the face of increasing difficulties in emerging markets. These difficulties have arisen for a number of reasons—weaker-than-forecast demand, regulatory pressures or a misunderstanding of consumers. One US-based retailer, for example, recently announced the closure of a store format in China poorly suited to local customers.

According to Accenture’s research, many executives fear they are missing the boat – 73 percent believe they need to accelerate their efforts, or may already be too late, to build satisfactory market share in today’s high-growth markets. Inorganic growth has also been more elusive. M&A deals in 2012 were down in both volume and value in comparison with the figures for 2011, itself roughly half the high-water mark achieved in 2007.

Yet there remains at least one area of significant growth that still has a great deal of headroom: consumer behaviour change. In developed markets, much of that change is being brought about by consumers themselves—including changes in the ways they prefer to shop and buy, and changes in the reasons why they buy. And with change comes opportunity. Those businesses that have the best understanding of consumer behaviour will prosper, no matter the top-line economic growth numbers.

The changing way we buy

The past decade has witnessed a huge technological revolution, precipitating the mass adoption of consumer technologies. The proportion of the world’s population using the internet quadrupled from 2001 to 2011. The use of consumer technologies in the consumption process has been seized upon by businesses. E-commerce, m-commerce, and social media all play an important role in the strategies of most consumer-facing companies, and many new entrants have built successful business models on just one strand of this.

Online consumption is more than just a niche, and it’s more than just transactional. Our survey points towards the rise of a “networked consumer” – one who is continuously in a retail channel, never far from an internet connection; one who is ever more social in online interactions; and one who is more than just a reactive consumer. They are also participants in the production process. Consider these developed-market data points: compared to three years ago, 65 percent of developed-market consumers are using the internet more to research products and services. Over a third (34 percent) of developed-market consumers are using social media more often to interact with friends and family. And 30 percent of developed-market consumers are providing more online feedback to companies about their products and services.

Some businesses are seizing upon this opportunity, and have adapted their offerings to the networked consumer. As the world went digital, education giant Pearson was one of the first to move from textbook to e-book. Pearson saw digital disruption as a sizable opportunity to better serve students and teachers. Accordingly, the company revamped its offerings to accommodate a connected lifestyle. Education services such as software and IT support have replaced textbooks as Pearson’s primary source of income, while acquisitions of EmbanetCompass and other online learning platforms are expanding the company’s presence in universities. Pearson’s education group has experienced a 93 percent increase in operating profits between 2007 and 2011, outpacing the profit growth of its publishing divisions.

Creating a unified educational experience between offline services and online educational products underpins Pearson’s move to digital education. For example, Pearson provides the technology infrastructure for universities offering “massive open online courses” (MOOCs) to anyone around the world. If students want to receive accreditation for their MOOC, they can go to one of more than 4,000 physical testing centres operated by Pearson worldwide. The company has also developed mobile apps to connect teachers, students and parents on a common platform for sharing student information. Pearson’s publishing arms have also been first movers in shifting to digital; for example, Penguin India was the first Indian publisher to launch an e-book program, while the Financial Times Group’s FTChinese MBA Gym App has become one of the best-selling education apps on iTunes in China.

The evolution of why we buy

It’s not just how we buy that’s changing – it’s why. Developed-market consumers are involving others in their buying habits. They are becoming increasingly “co-operative,” placing a strong emphasis on responsible production and consumption. They are devoting time and money to social causes; buying local or making when they could be buying; and re-using, re-cycling or sharing products that previously they might have owned outright. There are many potential reasons for this trend – a shared sense of responsibility, for example, borne out of increasing awareness of environmental problems. Or, it could be a need to re-connect with others in an increasingly fragmented society. Recessionary pressures may also play their part, by making shared ownership the wallet-savvy option.

These developments have crossed over from the few to become mass-market. One in three (32 percent) of developed-market consumers we surveyed are considering the environmental impacts of purchases more often now than three years ago. Thirty-five percent are buying locally sourced or made products more often. One in four (25 percent) are more often buying or using things that were previously owned by someone else.

Some businesses have been quick to respond to these trends. eBay is an engine of the exchange economy, having founded its business model on connecting buyers and sellers of used goods. Since then, a crop of companies has emerged to distribute and share under-utilised assets – be it cars (such as Zipcar and others), office space (Loosecubes), accommodation (Air BnB), or human capital (for example, Mechanical Turk and Fiverr).

Some businesses are recognising the disruptive threat of these business models – Hertz, the global car rental company, created its own car-share service, now called Hertz On Demand, in 2009. Hertz On Demand grew to 130,000 members by May 2012, and its success helped the company set quarterly records in revenues and pre-tax income in the second quarter of 2012. The minimalist approach of Hertz On Demand has carried over into Hertz’s other services, from the introduction of “virtual kiosks” to a partnership with a recycling company to dispose of old tires. The company has eliminated the payment obligations of membership, annual and late fees, and now offers one-way car rentals in parts of the United States to lessen the hassle of rental returns.

Other companies have intertwined social and environmental good with the economic bottom line. Whole Foods Market has long recognized consumers’ increasing desire for healthy lives and healthy communities. In 1985, Whole Foods Market’s “Declaration of Interdependence” described the company’s commitment to operating communally, prioritizing the shared well-being of employees, customers, communities and the environment in its corporate practices. Whole Foods Market has only deepened its commitment to communal conduct over the years. The company has formally labelled itself as a “conscious business,” where social and environmental goals are pursued as greater ends than profits. Whole Foods Market now provides customers with environmental ratings for its groceries as well as health education programs, bridging the gap to consumers by sharing their communal sensibilities.

How to respond

These types of behaviour change present a double-edged sword for businesses in developed countries. On the one hand, they offer an avenue of growth by creating new markets and platforms for competition – e-commerce platforms, for example, have allowed even the smallest retailer to access a global customer footprint. But disruptive consumer change also has the power to oust incumbent players. The successive failure of high street retailers in the UK, a seemingly endless list including Jessops, HMV, Comet, Blacks, Woolworths, Barratt, Habitat, and Game, bears testament to this.

So how must companies respond to “networked” and “co-operative” consumers?

1. Use consumer data to inform strategy

With more and more purchasing activity taking place online, the amount of data available on consumer preferences is expanding all the time. Companies must gather this data, not just to hold it on a hard drive, but to use it to inform product offers and internal decision-making. Netflix’s Cinematch algorithm cultivates film rental ideas for consumers based on past search histories, giving the company a competitive edge. North American retailers have used consumer analytics to anticipate demand for certain products, and have used this knowledge in turn to optimise their supply chains and distribution channels.

2. Provide platforms for consumer interaction

Networked consumers seek social interactions with other consumers, and increasingly with companies themselves. Leading companies are building platforms to allow their consumers to communicate. Aside from being a way to find out what consumers are saying, this approach can yield substantial advantages further down the line. Online writing forum Authonomy lets users rate and review works from unpublished authors to help publisher HarperCollins identify and cultivate the next generation of authors. Threadless, an internet clothing company, encourages designers to upload t-shirt motifs, then chooses which to print and sell based on customer ratings, guaranteeing that winning designs match customer demand.

3. Explore different business models based on access, not ownership

As consumers become more averse to buying outright, the demand for shared, rented, exchanged and pre-owned goods will rise. Few businesses are immune to this type of threat – even luxury handbags are being rented out by the likes of Bag Borrow or Steal. Companies must be willing to experiment with edge-of-the-radar ideas for revenue generation, even if it may seem anathema to the core business

4. Seek to intertwine the greater good with economic results

In an era of more conscientious consumerism, buyers are expecting sellers to be more responsible global players. Profitability and the greater good are no longer mutually exclusive, as concepts such as “triple bottom line” and “shared value” have illustrated. Companies must be good to the core, ensuring suppliers, distributers and partners are similarly minded, and even encouraging consumers to adopt more sustainable practices.

Executives will find that incorporating these capabilities into their businesses requires investment, and in today’s constrained world it may be difficult to justify such expenditure. However, targeting the changing consumer, and the opportunities that presents, represents an undervalued yet important route to growth for businesses in developed markets.

About the Authors

Paul F. Nunes is managing director of research for the Accenture Institute for High Performance. Sam Yardley is a research fellow with the Institute. Mark Spelman is managing director for management consulting thought leadership at Accenture.