By Luis Ballesteros, Michael Useem, and Tyler Wry

Summary

Natural disasters have been growing in their social impact in recent years, but humanitarian assistance has not kept pace. Company donations have fortunately made up for some of that shortfall. By 2015, more than 90 percent of the 3,000 largest companies worldwide have been contributing to disaster relief. Addressing a long-standing issue of whether corporate social responsibility benefits or costs companies – and whether it also benefits the receiving societies, we drawn on a data base of the donations of large companies in the wake of natural disasters worldwide from 2000 to 2015. We report that companies do benefit if their contributions are well managed, as when they are directed to countries where the company already has local operations, and where the company has previously established a favorable local reputation. We also report that when company aid is so directed, it significantly adds to the country’s recovery. The evidence confirms that company giving, when well managed, benefits both the firm and the society. We offer a relief roadmap for business leaders in the wake of great natural disruptions, including the Covid-19 crisis of 2020.

It was early January in 2020. The coronavirus was already throwing out frightening signs of its potential for economic devastation. General Motors, Honda, Nissan, and other carmakers with plants in the most affected Chinese city of Wuhan had closed their lines. Employees could not work, suppliers had shut down, and customers postponed purchase. By April, the disruption has spread globally and into virtually all industries, from financial services and travel services to construction and technology. Some firms responded by moving into products for testing, combatting, or treating the pandemic. Luxury firms shifted to protective masks, alcoholic-beverage makers to hand sanitizers, and automakers to ventilators. Are these actions economically efficient? And can company engagement in tackling great challenges help societies recover from their disruption?

More Disasters, Less Relief

Three hurricanes hammered the U.S. in just two months in 2017, leaving a $200-billion swath of destruction from Puerto Rico to Texas. Several months later, a raging wildfire destroyed more than 8,500 buildings in Northern California. It was a frightful year abroad, too. A magnitude-8.2 earthquake rocked Mexico, monsoon flooding killed 1,200 in Bangladesh, and extreme temperatures scorched India.

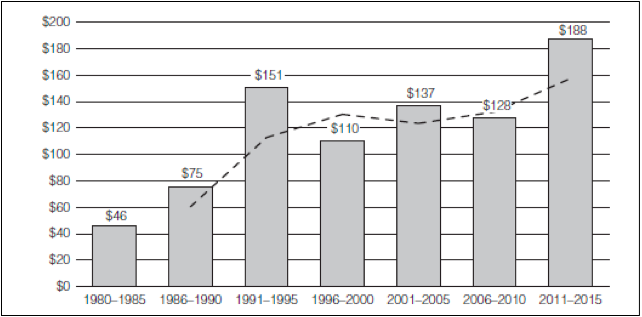

But 2017 had not been the worst year on record. That dreary distinction had belonged to 2011, when the costs of natural disasters worldwide exceeded $350 billion. Yet the long-term trend line was unmistakably upward: The inflation-adjusted cost of global calamities half-decade by half-decade had been rising, and was up more than four-fold since the early 1980s, as seen in the figure below.[1]

The figure shows the annual global cost of natural disasters in $ Billions, in 2016

prices adjusted for inflation.

Yet even those unhappy statistics have been completely eclipsed in 2020 by the global explosion of the Coronavirus. Its remorseless expansion across the U.S. and abroad – daily life in India, Russia and much of Europe had been forced to shut down too – made the routines of hundreds of millions virtually unrecognizable. America’s unemployed soared by millions, equity markets shrank by trillions of dollars, and economies almost everywhere suffered cardiac arrest. The U.S. Congress authorized $2 trillion as a stimulus, the U.S. GDP was forecast to fall by two percent or more, and S&P 500 companies were expected to deliver their worst performance since the financial meltdown of 2008.

The number of people affected by natural disasters is also staggering. During the 1960s, fewer than 100 million victims per-year worldwide required food, water, shelter, or medical assistance after natural disasters. More recently, that yearly toll soared over 300 million. And then with Covid-19, the number of victims jumped by an order of magnitude. Making matters worse, traditional sources of disaster assistance have not kept pace. Never before, reported the U.N. in 2015, has humanitarian aid in response to catastrophic events “been so insufficient.” And now, the pandemic of 2020 is sure to render that a radical understatement.[2]

Companies Fill the Breach

Fortunately, private sector donations have made up for some of the humanitarian shortfall. We found in our own detailed look at the 3,000 largest companies worldwide, for instance, that while less than a third had contributed anything to disaster relief in 2000, by 2015 more than 90 percent were doing so, and on average they had increased their donations tenfold.[3]

The fraction of the 500 largest American corporations giving disaster relief soared as well, from less than 20 percent in 1990 to more than 95 percent by 2014. A manager at Coca-Cola spoke for many in explaining why his own firm was giving in Japan after its magnitude-9.0 earthquake in 2011: “We are part of a system,” and if the government cannot effect a recovery, “we need to rebuild” since “we need the market to recover.”

So widespread and substantial has corporate giving become after natural disasters that company donations in the aggregate have sometimes come to exceed all other forms of international aid. Following a magnitude-8.8 earthquake in Chile in 2010, firms contributed more to national relief than that did foreign governments, private foundations, and multilateral agencies combined. The same after the magnitude-9.0 earthquake in Japan in 2011 that killed more than 24,000.

There are many drivers behind rising company support for disaster relief, but we believe one of the most important has been an expanding engagement of companies in a host of social arenas. After an armed assailant killed 17 students and teachers in Parkland, Florida in 2018, for example, a number of companies including Walmart and Dick’s Sporting Goods decided to limit their sales of firearms. Dick’s, for one, raised the age for buying firearms to 21 and ended sales of AR-15 assault rifles altogether. Companies have also increasingly felt that rising activism in reverse. When Delta Air Lines severed a partnership with the National Rifle Association following the Parkland massacre, the Georgia state legislature rescinded a tax break for the airline.

With the rising company engagement across a spectrum of social issues, this is a good time to put the two most fundamental questions regarding corporate social responsibility – CSR – in front of us once again. The first is whether company CSR is good for the company itself. Economist Milton Friedman resoundingly answered in the negative, proclaiming that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits” and anything else was irresponsible. But is that true? Does corporate giving in fact hurt a firm’s performance? And the second question, if we get by the first, does corporate social responsibility really benefit the society?[4]

New evidence we have gathered on company giving in the wake of natural disasters offers a resounding but qualified yes for both questions. As we shall see, the impact very much depends on where and how companies give their aid. In other words, it is a question of company leadership. Done well, both business and society benefit, but if less-well done, neither gains. And companies can even lose, confirming Friedman’s counsel against CSR, in this case when company aid is misdirected.

First Movers Are Trend Setters

Given the rising costs of natural disasters and the expanding gap between traditional sources of emergency aid and post-disaster needs, corporate giving has become an accepted practice among large enterprise. And as a result, falling short of that norm risks censure from both company stakeholders and other firms, especially. And that norm was further strengthened in 2019 when the Business Roundtable, an association of some 200 large American company CEOs, declared that large firms should move away from a singular focus on shareholder value and embrace a boarder commitment to customers, communities, employees, and suppliers as well. Not surprisingly, then, companies look to one another for guidance on how much to give.[5]

In fact, company imitation of one another has become almost universal. Our data show that in 89 percent of natural disasters worldwide from 2000 to 2015, the donation of the first corporate giver was almost exactly matched by later givers even though the latecomers differed greatly in their own market value, market share, and financial performance. Within hours of Chile’s 2010 earthquake, for example, multinational mining company Anglo American pledged $10 million for relief, the first major private donor to step forward, and in the days that followed, three other major competitors – Antofagasta, Barrick, and BHP Billiton – pledged identical amounts.

Our analysis also reveals that the followers’ level of giving depends more upon what other companies have already donated than on their own ability to contribute, or the scale of the disaster damage itself. Business norms have thus become important drivers of corporate largesse. First movers, as a result, are also trend setters, defining what others will give regardless of the latter’s capacity to give or the country’s need for relief.

Doing Well by Doing Good – If the Good is Well Led

But in following one another, can firms indeed do well while also doing good, as proponents of corporate social responsibility have long argued? We have found that the answer is a qualified yes, with company gains entirely dependent on whether the largesse is well managed. And for that, we have identified four practices from our data that will help companies do well for themselves when doing good. For this purpose, we have studied company subsidiary’s “off-trend revenue,” that is, their local income that is substantially above or below recent trend lines for that operation.

Company Giving Brings Company Advantage in Countries Where the Giver Operates

We discovered that company giving brings advantage to companies in countries where they have local operations, but not elsewhere. The off-trend revenue gain for companies with local operations is in the millions of dollars, but worldwide gains are close to zero where they do not.

In the case of Chile’s 2010 earthquake, for example, the companies Anglo American, Antofagasta, Barrick, and BHP Billiton all had major operations and each pledged $10 million for relief. Here we find that the local off-trend revenue for all gained significantly, a sign that their donations were visible and valued by disaster victims, public officials, and business customers.

Company Giving Brings Advantage but Only if the Firm’s Reputation is Good

We find that disaster giving benefits firms with good pre-disaster reputations, but has the opposite impact on firms with poor pre-event reputations. A first mover with a positive standing gains more than $50 million in off-trend revenue compared to a first mover with negative repute. Moreover, the revenue gains or losses far outstrip the cost of the giving itself. For a first mover with a positive reputation, for instance, its revenue gain is 18 times greater on average than the size of its gift, and for those with a negative reputation, the loss is 12 times greater than the size of that gift. Speaking of leverage!

A case in point: In the aftermath of a magnitude-8.0 earthquake in 2008 that devastated Sichuan, China, Samsung pledged a gift of $8.3 million. Samsung had been earlier accused of unethical local labor practices, and it experienced a public backlash over its gift that included consumer boycotts of its products, resulting in negative off-trend revenue. Samsung gave, but it also paid twice, first the generous gift and then the lost revenue.

Second Movers Gain from Imitating Well Regarded First Movers – But Not Others

We also find that second movers, regardless of their own pre-disaster reputation, are wise to follow well-regarded first-movers but not to replicate poorly-regarded first movers. The imitator of a reputable first mover realizes an off-trend revenue gain of $19 million on average, while the imitator of a first mover with a negative reputation suffers a loss of $38 million, a 51 million-dollar difference between the two.

Nokia and Panasonic had imitated Samsung’s lead in Sichuan, China, but rather than being hailed for their generous gifts, they too were criticized for what looked like “a drop in the bucket,” and both suffered from a decline in local off-trend revenue after the disaster. By contrast, Sony gave later and less than Samsung, but gained revenue.

By implication, in the aftermath of a natural disaster, including the Coronavirus of 2020, second-giver companies will want to carefully study the first-mover’s local reputation. If favorable, then replicating the first mover’s giving level is advantageous, but if troubled, then copying it is ill-advised. The second mover is better off giving either more or less, just not the same.

Moreover, it doesn’t matter for the company whether it gives money or material. And equally, it doesn’t matter if the firm donates a huge or more modest amount. Just a substantial contribution of some kind is needed.

Doing Good by Doing Good

While the value of corporate giving for natural-disaster victims is generally assumed but rarely proven, our analysis also reveals that it does more good than harm – but primarily when the contributing companies already have their feet on the ground – giving a qualified answer to the first questions of whether CSR is actually good for intended beneficiaries.

When firms have operations in an afflicted region, as Walmart did in the hurricane ravaged Gulf Coast, they are often better than outside agencies at identifying what is needed on the ground – and can tailor their responses accordingly. Logistics companies like FedEx, UPS, and DHL are well informed on how best to donate delivery services for disaster relief where they have pre-existing ground operations. Telecommunications companies like AT&T and Vodaphone are well positioned to ramp up emergency service in regions where they already have wireless operations.

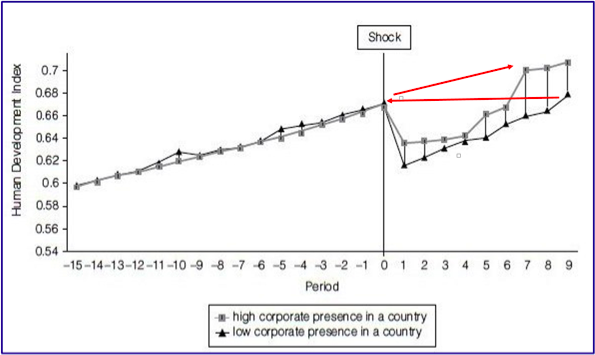

Locally-embedded company largesse, we have found from our data, adds significantly to a country’s social recovery following a disaster. To see this, we drew on a widely-used social index for nations that is calculated annually by the United Nations. This Human Development Index incorporates national data on health, education, and living standards, including life expectancy, years of schooling, and GNP per capita. While the index does not capture other important social benchmarks, such as a nation’s inequality, poverty, or insecurity, it provides a broad-based measure of a country’s social well-being.

Drawing on data for natural disasters worldwide from 2003 to 2013, we found that a nation’s Human Development Index declined after a disaster to a level that the country had not experienced for as much as ten years. In other words, natural calamities can wipe out a full decade of a nation’s development in an instant, a statistical testament to their devastating and prolonged aftermaths.

Even more striking are the different national pathways when we break natural disasters into two subgroupings. The first consists of disasters in which more than 10 percent of the international post-disaster aid came from companies with operations in the afflicted country. Those companies had a direct interest in assisting recovery, could quickly furnish essential supplies and equipment, and had local knowledge of how best to distribute them. The second subgroup consists of disasters in which less than 10 percent of the international post-disaster aid came from companies with a substantial local footprint.

An example of the first subgroup was international post-disaster assistance coming in to Chile after its earthquake in 2010, where companies like American Airlines and Walmart had local operations and donated generously. An example of the second subgroup was post-disaster assistance to Nepal after its 7.8-magnitude earthquake in 2015, where little business aid flowed in from multinationals with local operations since so few had any presence in the country at all.

We tracked the Human Development Index for countries from fifteen years before a disaster to nine years after, as displayed in the figure below, broken down by these two subgroups. We see a significant and enduring gap between the two groups in the metric for social recovery in the years following a national disruption. Nine years after the calamity, the Human Development Index for countries without much corporate relief from locally-operating companies had barely recovered to pre-disaster levels, as indicated by the lower arrow in the graph below.

The figure shows the impact of natural disasters on the United Nation’s Human Development Index for countries nine years after the disasters. The data are for natural disasters in which companies with local operations gave at least 10 percent of the international post-disaster assistance, an indicator of higher corporate presence and engagement in a country, and for disasters in which companies with local operations gave less than 10 percent of international post-disaster assistance, an indicator of lower corporate presence and engagement.

Yet for countries with a more substantial fraction of aid coming from firms with local operations, the Human Development Index rose far more rapidly after several years, restoring the country’s development trend line after seven years as if it had suffered no disaster at all, as shown by the graph’s upper arrow. Summed up, when companies are locally rooted and step forward with assistance, afflicted countries are fully back on their upward development path within little more than half a decade. But when locally-based companies fail to step-up, countries lose a decade of social development.

These outcomes are even more striking when companies donate aid that builds on their core competencies. General resources like cash donations are certainly useful, but significant unique value is created when a company lends not just resources, but also expertise. For example, after a tsunami devastated Sri Lanka in 2004, Coca-Cola used its soft-drink production lines to bottle water that it distributed to victims using company trucks. In our studies, we see such in-kind donations increasing the effectiveness of corporate aid by as much as 56 percentage points.

Disaster Strikes, and You’re in Charge

Imagine that you are responsible for Walmart’s operations in Texas or Louisiana when three powerful hurricanes sweep through your region just weeks apart. Or that you are in charge of one of Chile’s largest mining companies when the nation is hit by the sixth most powerful earthquake in recorded history. Or you are a manager of almost any American corporation when state governors and city mayors required millions of Americans to shelter-in-place.

Extending into unnatural disasters as well, you are a leader of Facebook when it is revealed that a British firm had improperly extracted data on more than 87 million users to assist the campaign of Donald J. Trump for the American presidency. Or you are the chief executive of Volkswagen or Wells Fargo when employees faked emissions equipment for the automaker’s vehicles or opened fake accounts for the bank’s customers.

Whether a top executive or operating manager, we all become responsible in a crisis, and a speedy response is of the essence. Experts on disaster recovery have long stressed immediate intervention for saving lives, restoring services, and rehousing the homeless. Consistent with this prescription, we have found that 83 percent of corporate aid is delivered within a month of a disaster.

Yet that is also the time when uncertainty most abounds. Every disaster is different, and detailed information about its devastation is often scant for months. As a result, uncertainty about a company’s proper response is likely to soar in the immediate wake of most disasters, as it has during the 2020 pandemic. A company’s rush to assist then – the time when it is most essential for the victims – is also the time when the risk of mismanagement is greatest, potentially resulting in a firm doing unwell for itself even if doing good for others.

To reduce that uncertainty and risk, here is a leader’s roadmap from our research for making crisis-driven relief decisions that result in all doing well, business donors and disaster victims alike. Like a pilot’s preflight checklist or a surgeon’s pre-operative checklist, we commend seven principles to keep in mind when you or your firm is operating in a region that has been struck by a terrible disaster – or even in a world where everybody has been touched by a deadly infection.

| A Relief Roadmap for Business Leaders |

| Give: With the rising costs of natural disasters and growing gap between traditional aid and post-disaster needs, companies are increasingly giving, and they are giving greater amounts to disaster relief. It has become a near universal norm among large companies worldwide, and falling short of that norm risks censure from both business leaders and public leaders in disaster-prone zones.

Give Where You Operate: The greatest value of company giving for disaster victims is achieved in countries where companies have an operating presence. Local business giving can restore a nation’s development path to its long-term upward trend, while its absence can impair a nation’s development for a decade. Give your Expertise as Well as your Money: The most effective responses to natural disasters leverage a company’s core competencies. Tailor your response around what you’re already good at doing. Improve Market Performance Through Non-Market Intervention: Providing company assistance in the aftermath of natural disasters improves company performance in countries where the firm operates, reaffirming but also qualifying the dictum of “doing well by doing good.” Give Generously if a First Mover (but only move first if you have a good reputation): The first company to make a post-disaster donation sets a benchmark for others to follow, and the multiplier of a generous first contribution by a locally operating company can enhance a country’s recovery well beyond the size of the first mover’s gift. Companies with a strong pre-disaster reputation receive outsized benefits from their gifts. However, those with negative reputations are more likely to be punished. If a Second Mover, Give as Well-Regarded First Responders Have Already Contributed: Second-moving firms do well in market performance if they give in ways similar to highly-regarded first movers – but not well if their donations copy those of poorly-regarded first movers. Analyze the Impact of Your Company’s Disaster Relief: Company contributions after disasters in countries where they operate have a measurable and significant impact on a nation’s comeback, and also a measurable and significant effect on the company itself. Managers are wise to track, analyze, and learn from their impact on a country’s disaster recovery and their own firm’s performance – giving analytics – for refining their long-term social strategy as part of their company’s business strategy. |

About the Authors

Luis Ballesteros is Assistant Professor of International Business at George Washington University

Luis Ballesteros is Assistant Professor of International Business at George Washington University

Michael Useem is Professor of Management at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Michael Useem is Professor of Management at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Tyler Wry is Associate Professor of Management at the Wharton School.

Tyler Wry is Associate Professor of Management at the Wharton School.

References

[1] Graph from H. Kunreuther and M. Useem, “Mastering Catastrophic Risk: How Companies Are Coping with Disruption” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); based on data from Munich Re Geo Research, “Loss Events Worldwide 1980-2014,” 2015.

[2] United Nations, “Too Important to Fail — Addressing the Humanitarian Financing Gap,” 2016, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/%5BHLP%20Report%5D%20Too%20important%20to%20fail%E2%80%94addressing%20the%20humanitarian%20financing%20gap.pdf

[3] This article draws on several of our studies, including those reported in L. Ballesteros, T. Wry, and M. Useem, “Halos or Horns? Reputation and the Contingent Financial Returns to Non-Market Behavior,” Working Paper, 2020; “Masters of Disasters? An Empirical Analysis of How Societies Benefit from Corporate Disaster Aid,” Academy of Management Journal, 60 (2017): 1682-1708; and H. Kunreuther and M. Useem, “Mastering Catastrophic Risk: How Companies Are Coping with Disruption” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[4] M. Friedman, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits,” New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970.

[5] Business Roundtable, Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans,’ August 19, 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.