In our globally expanding economy, it is no longer enough for successful managers to have great directive skills, they must also be able to understand and adapt to the different cultures they operate in. The recently published Management Across Cultures: Developing Global Competencies (Cambridge University Press) takes a look at the ideological challenges managers are faced with and proposes different strategies for developing greater multicultural competence.

Introduction

IBM executive Michael Cannon-Brookes recently observed, “You get very different thinking if you sit in Shanghai, Sao Paulo, or Dubai than if you sit in New York.” All too often, the essence of this observation is lost on global managers—and would-be global managers—as they seek to make their way in an increasingly complex and nuanced business environment.Many managers working across borders fail to recognize that not everyone agrees with their perception of the facts; not everyone agrees on the meaning of a contract; not everyone agrees on how to lead a company; and, indeed, not everyone agrees on the proper role of supervisors and managers themselves. Uncertainty—and, more importantly, ambiguity—faces managers at every turn. And increasingly, managers realize that that much of what they believe they see around themselves is often something entirely different. Why does this occur with alarming regularity? And what can informed managers do to moderate or attenuate the impact of such contradictions?

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]We live in a turbulent and contradictory world, where there are few certainties and change is constant. Over time, we increasingly come to realize that business cycles are becoming more dynamic and unpredictable, and companies, institutions, and employees come and go with increasingly regularity. Much of this uncertainty is the result of economic forces that are beyond the control of individuals and major corporations. Much results from recent waves of technological change that resist pressures for stability or predictability. And much results from individual and corporate failures to understand the realities on the ground when they pit themselves against local institutions, competitors, and cultures. Knowledge is power when it comes to global business and, as our knowledge base becomes more uncertain, companies and their managers need to seek help wherever they can find it.

Considering the amount of knowledge required to succeed in today’s global business environment and the speed with which this knowledge becomes obsolete, developing an ability to work successfully with partners in different parts of the world is possibly the best strategy available to managers and companies that want to succeed. Business and institutional knowledge is transmitted through interpersonal interactions and, if managers are able to build mutually beneficial interpersonal relationships with partners around the world, they may be able to overcome their knowledge gaps.

We suggest that what often differentiates effective global managers from less effective ones is not so much their managerial skills – although this is obviously important – but the combination of these skills with additional multicultural competencies that allow people to apply their managerial skills across a diverse spectrum of business environments.

What is multicultural competence?

Whether relocating to a foreign country as an expatriate, traveling around the world as a frequent flyer, or dealing with foreigners in one’s home country, managers often face important cultural challenges. Different cultures have different assumptions, behaviours, communication styles, as well as expectations concerning management practices. The ability to deal with these differences in ways that are both appropriate and effective goes by many names, but we refer to it simply as multicultural competence (MCC).

MCC represents the capacity to work successfully across cultures. Being multiculturally competent is more than just being polite or empathetic to people from other cultures; it is getting things done through people by capitalizing on cultural diversity. It includes skills such as identifying cultural rules, changing and creating group cultural norms, communicating across cultures, dealing with conflict, developing trust based relationships, understanding the constraints and opportunities imposed by the micro-context of an interaction, and manipulating those when appropriate.

Developing multicultural competence

Developing global managers is no easy task. Indeed, a pivotal question facing both training directors and managers themselves is exactly how global managers can be developed. As a result, managers often turn for advice to those who specialize in cross-cultural training and development for help in preparing for foreign assignments. But this over-reliance on others – instead of on oneself – can carry risks. Much has been written on the topic of developing global management skills, and much of what has been written is contradictory, simplistic, and sometimes simply incorrect. Successful global managers tend to rely on themselves, including their own perceptions and assessments of what is going on in the world. They often require personal insight more than outside advice. Indeed, what often differentiates successful global managers from unsuccessful ones is that they have developed a way of thinking about the world that is flexible and inclusive and guides their behaviour across cultures and national boundaries.

Consider how Google is training its new generation of managers. Google is now sending its young ‘brainiacs’ on a worldwide mission.1 One recent group of trainees began their journey in a small village outside of Bangalore, India. There were no computers in the tiny village, only unpaved roads surrounded by open fields where elephants roamed and trampled local crops at will. The visit was aimed at educating Google associate product managers about the humble, unwired ways of life experienced by billions of people around the world. On their first day in Bangalore, the visitors went to the Commercial Street shopping district for a bartering competition. Each Google manager was given 500 rupees (about $13) to spend on ‘items that don’t suck,’ with a prize given to the one who attained the highest discount on the purchase. For most, it was the first time they had to bargain with street vendors. “I usually shop at Neiman Marcus,” observed one manager, after she bargained the price of a necklace down from 375 rupees to 250. But one of her colleagues won the competition by purchasing a deep-burgundy sherwani – a traditional Indian outfit – for one-third of the original asking price. The journey continued, as did the learning.

The example of Google’s traveling managers illustrates how this and many other companies search to find unique ways to educate their managers about both the global challenges facing them and the strategies that can help them succeed. In the case of Google, managers were intentionally placed in unfamiliar circumstances where they quickly had to seek understanding and be aware of their first-hand experiences. They needed to reflect and make sense of these experiences and identify important lessons for the future. At the same time, these managers had to organize what they saw and develop theories-in-use for future actions that could be tried when they returned to the field. Note that Google went to great lengths to allow their managers to fail as well as succeed. Note, too, that there were few safety nets.

Experiential learning and informed sense-making

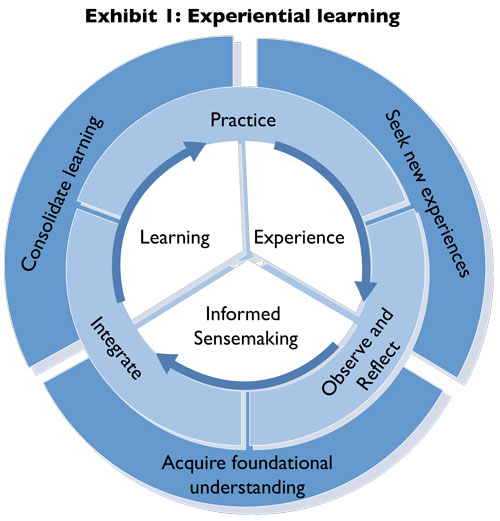

Google’s strategy is in line with research on experiential learning.2 This body of research suggests that we learn through experience if we are able to reflect and make sense of those experiences and transfer this understanding into new theories of action that will guide our future behaviour. As illustrated in exhibit 1 (two center circles), learning is a result of observing, reflecting and making sense of experience. This “processed” experience can than be integrated into learning that will guide future experiences and sensemaking efforts.

Experience alone does not guarantee learning; the world is full of repeated mistakes. In order to learn from experience it is necessary to make sense of what happened, understand the causes of problems, the strategies that worked and the ones that didn’t, and more importantly understand why things turned out the way they did. We refer to this process of reflection and understanding as informed sensemaking, to highlight the fact that a heightened level of self- awareness and understanding of the processes surrounding the experience and the context of the experience is necessary. Inexperienced managers engaging in a cross-cultural situation may be able to notice symptoms, such as a difficulty to negotiate an agreement with a foreign partner, but may not be able to understand the causes of that difficulty or identify possible solutions.

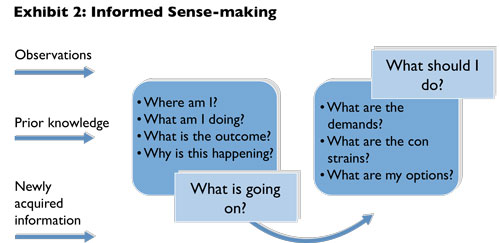

Multiculturally competent managers are able to make sense of situations by seeking answers to two main questions: “what is going on here?” and “what should I do?” “What is going on here?” involves an understanding of the situation where the manager is – is this interaction happening at home, at the business partner’s territory, or somewhere else? It also involves an awareness of one’s own actions – how am I behaving? Is this behaviour appropriate? Is this behaviour helping me to achieve my desired outcomes? It also requires a reflection on the reasons behind what is happening. Why am I unable to reach an agreement? Is it a communication problem, or is it the result of an incompatibility of goals?

With a deep understanding of what is happening, managers can then answer the question “what should I do?” Here it is helpful to think of a simple model of managerial choice and action originally introduced by Oxford University Professor Rosemary Stewart.3 Stewart makes a cogent argument for rethinking our approach to management, global or otherwise. The model’s central argument is that all managerial work is confined in varying degrees by existing demands (what people must do) and constraints (what people must not do). However, within these limitations, managers typically have choices about what is done and how it is done. This is where managerial abilities and skills take centre stage. The challenge for the manager is to understand the constraints—cultural, organizational, and situational—within his or her environment and then act within these limitations.

As illustrated in exhibit 2, informed sensemaking relies on observations and prior knowledge as well as in an active search of information to understand what is going on. As managers try to make sense of an on going situation they rely on their observation skills to identify as many cues as possible regarding the current situation. They draw upon prior knowledge and experience in order to look for similar situations that can provide insight into the present, and they seek out the missing information through multiple means, including asking questions when appropriate, consulting with more experienced individuals, or testing alternative scenarios.

What differentiates multicultural competent managers from others is that they have sophisticated models of culture and human behaviour that are situationally dependent. They have a deep understanding of how and when culture influences behaviour and they continuously refine their models as they engage in new cross-cultural situations. The challenge facing inexperienced managers is to develop a foundation of understanding that will allow them to make sense of their first cross-cultural experiences and use them as a platform for further learning.

Strategies for developing multicultural competence

Multicultural competence is obviously not a have-or-have-not proposition; it is a matter of degree. Most managers by their very education and experience understand how behaviours can differ across cultures. The challenge, therefore, is to enhance this set of skills in ways that managers can capitalize on when the find themselves “in the trenches.” To accomplish this, we suggest three principal strategies, illustrated in exhibit 1 (outer circle):

1. Acquire foundational understanding

As a starting point, global managers can work to enhance their knowledge and awareness of human behaviour and how it can be influenced by cultural and contextual variables. This knowledge can be instrumental in facilitating sensemaking when a manager is exposed to novel situations. This understanding may be acquired through seeking information about culture and human behaviour in general, as well as specific cultures of interest, and by reflecting upon their own and others’ experiences, observations, and analyses. The goal here is to better understand why other people did what they did, not necessarily to evaluate it. As managers progress in their global career and are increasingly exposed to other cultures and contexts, this foundational knowledge will expand and become more sophisticated.

Managers can also work to enhance their own self-awareness and understanding. Self-learning may sound a little esoteric and disconnected from the business world, but it is probably one of the most critical tools for a successful global career. Being self-aware means knowing one’s own values, beliefs, styles, and patterns of behaviour, and being able to explain these to others. It also includes recognizing when they are not having the desired effect. For example, a manager that is typically highly assertive or direct when communicating may need to adjust or explain his or her style in a cross-cultural setting in which individuals from other cultures expect more subtle and indirect ways of communicating. Given the innumerable situations facing global managers on a daily basis, it is clearly not possible to learn about all individuals and situations a priori, but knowing about oneself is already half of the work.

2. Seek multicultural experiences

People learn and develop based largely on their past experiences and past mistakes. 13th century Middle Eastern Mullah Nasrudin, once observed “Good judgment comes from experience; experience comes from bad judgment.” In our view, this is particularly noteworthy with regards to global managers. People try, make mistakes, and learn from those mistakes. This is the essence of experiential learning. Thankfully, multicultural experiences are easily available. In the world we live today, it is no longer necessary to cross the world to have a multicultural experience. With the high levels of global migration, many societies have multiple cultures represented. Seeking out different cultures in our own neighbourhood may go along way in sharpening our understanding of culture and human behaviour and developing a starting point for the development of multicultural competence. In addition, increasing arrays of short-term foreign experiences are available for aspiring global managers to hone their skills.

3. Consolidate learning: Develop theories in use or action plans

Once a manager has an understanding of what is required, the next step includes adjusting his or her behavioural strategies and creating, and then experimenting with, new action plans in the field. For example, the manager that has realized her tendency to direct and assertive communication, now needs to develop the skill to communicate more indirectly. From a managerial standpoint, the fundamental challenge is not just to learn but also to consolidate learning so it becomes an integral part of people’s daily routines.

Conclusion

In this article, we have argued that managers need both managerial and multicultural competencies to succeed in today’s complex business environment. As noted above, global managers must succeed equally in New York, Shanghai, or Buenos Aires, requiring enhanced insight and understanding into environmental and situational differences, as well as sufficient awareness and flexibility to adjust to unique situations on the run.

This required balance is both difficult to attain and sometimes even more difficult to maintain. Situations facing managers are highly dynamic and variable. As a consequence, there is just so much that managers can learn in preparation to the difficulties of global work, and a significant part of the learning must happen on the fly, as new situations emerge and evolve. The success of any cross-cultural interaction (and mono-cultural interactions as well) is the result of some type of interdependent learning in which the parties involved learn about each other’s goals, preferences, styles, and limitations, and negotiate ways of working together. This learning is a continuous and on going activity that overtime will shape the way a manager thinks and acts, but also will shape the situation itself. Throughout this process, the manager as a critical thinker becomes at least as important as the manager as an initiator.

This article is based on the recent book by the authors, Management Across Cultures: Developing Global Competencies (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

About the Authors

Luciara Nardon is an Assistant Professor of International Business at the Sprott School of Business, Carleton University. She has taught graduate and undergraduate courses in Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, and the US. Her research explores the role of culture on management practice, with particular emphasis on identifying skills and processes required to succeed in multicultural environments. Her latest publications include the book Management Across Cultures: Developing Global Competencies and articles in the Journal of World Business, Organizational Dynamics, and Asia Pacific Business Review among others. She is currently in the editorial board of the Journal of World Business.

Richard M. Steers is professor emeritus of organization and management in the Charles Lundquist College of Business, University of Oregon. His research interests include employee motivation, leadership, and cross-cultural management. He is a past president and fellow of the Academy of Management and currently Senior Editor of the Journal of World Business. His most recent books include Management Across Cultures: Developing. He has held academic appointments in England, Japan, the Netherlands, South Africa, South Korea, and the US.

Carlos J. Sanchez-Runde is SEAT-Volkswagen Professor of Work Relations at IESE Business School. He has hold visiting appointments at universities in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay and the US. His research centres on cross-cultural employee motivation and personnel practices. His latest work includes a forthcoming paper on cross-cultural ethics for the Journal of Business Ethics and the second edition of “Management across Cultures“, both coauthored with professors Nardon and Steers, and the teaching case “Haier in Japan” (IESE Publishing 2012, with professors Lee Yih-teen and Sebastian Reiche).

References

1. Steven Levy, “Google goes globe-trotting,” Newsweek, November 12, 2007, pp. 62–64.

2. Kolb, A. Y., and Kolb, D. A. 2005. Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4: 193-212. Nardon, L., & Steers, R. M. (2008). The New Global Manager: Learning Cultures on the Fly. Organizational Dynamics, 37(1), 47-59.

3. Rosemary Stewart, (1982). Choices for the manager. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Global Competencies (Cambridge University Press, 2013) and the Handbook of Culture, Organization, and Work (Cambridge University Press, 2009).