By Christoph Burger, Edward W. Boon and Nora Grasselli

A typical story

Jane is a manager at a large telecom company. Three months ago, she was promoted to head up a regional service center. As part of her development plan to take on this more challenging role, her manager has enrolled her in the organization’s mid-level manager training program. Jane is a believer in personal development, so she is pleased that she will be provided with training. Her motivation is high, but it’s unclear to her exactly how this training will support her new role; perhaps that will become clear later, she thinks. Jane attends the training program and thoroughly enjoys it; the faculty is both entertaining and inspirational. She learns a lot. Back at work, though, her new role is consuming a lot of time and energy. Jane struggles to find the time to apply all the tools and methods she learned during the training. And a lack of feedback makes her insecure if her new behaviors are working or not. Her action plan slips further down her priority list. Pretty soon, Jane has fallen back into her old routines and behaviors. A few months after the training, she receives an evaluation form asking about her experience of the training. She has no hesitation as she answers the first questions about the quality of the faculty and materials – full marks. She also confirms that the program equipped her with new knowledge and skills. However, as she reaches the part that asks her about examples of situations where she has applied her learning and the results she has seen, she clutches at straws. She struggles to give a concrete example of how the training has produced sustained behavioral change or lasting business impact. Jane’s story is common and illustrates the need for organizations to take a fresh look at how they see their executive education.

Executive Education must be seen as an investment

Sending executives to training is an expensive business. On top of the training cost, there is ‘opportunity cost’ of the participants not being at their desks, plus travel, food, accommodation, etc. It adds up. Yet, most organizations also recognize that not equipping their leaders with the knowledge and skills to lead the company effectively is a risk they are not willing to take. After all, the participants are in charge of forming a winning strategy and guiding the organization to meet those strategic goals. In today’s fast moving and ever-changing business environment, failure to invest in the development of the organization’s leadership capabilities is a one-way ticket to extinction. Top management increasingly realizes that they must see their executive education as an investment. And not just an investment in vague intangibles like ‘our people’s future’ but a true investment with expectations on return for the bottom line.

A good investment strategy starts by defining the expected return

As soon as we view the expected outcome of executive education not as learning but as business results, we need a totally new approach to training design. Traditionally, the first question of design is “What do we want the participants to learn?” This is misguided, and the rest of the initiative unravels. If we are serious about achieving business impact through training, the first question should be “What business outcomes would we like to see because of this intervention?” Next, we will ask questions like “How, where, and when do we need our leaders to perform better to achieve those business outcomes?” and “What specific knowledge and skills do we need to equip our leaders with to deliver the improved performance?”

Note that the question about knowledge and skills comes last, not first. The outcome of this results-first perspective is twofold. First, it ensures that the training content is aligned with the desired outcomes, leading to an effective design. Second, it ensures that the training only includes necessary content to produce the desired outcomes, leading to an efficient design.

We illustrate this approach through our work with one of the world’s largest commercial vehicle manufacturers, TRATON. The TRATON GROUP brings together four of the world’s leading truck brands – MAN, Scania, Volkswagen Caminhões e Ônibus and, most recently, Navistar. In 2019, the recently formed TRATON organization set out to become the global champion of the transportation services industry. To realize this vision, the TRATON Talent Development Strategy was established and, in a competitive bid, the Berlin-based business school ESMT Berlin and the Swedish training company Mindset were selected to support TRATON’s cross-brand program team in designing and executing the Management Excellence program, an investment in the strategically vital high-potentials, who were hand-picked from the first-line management pool.

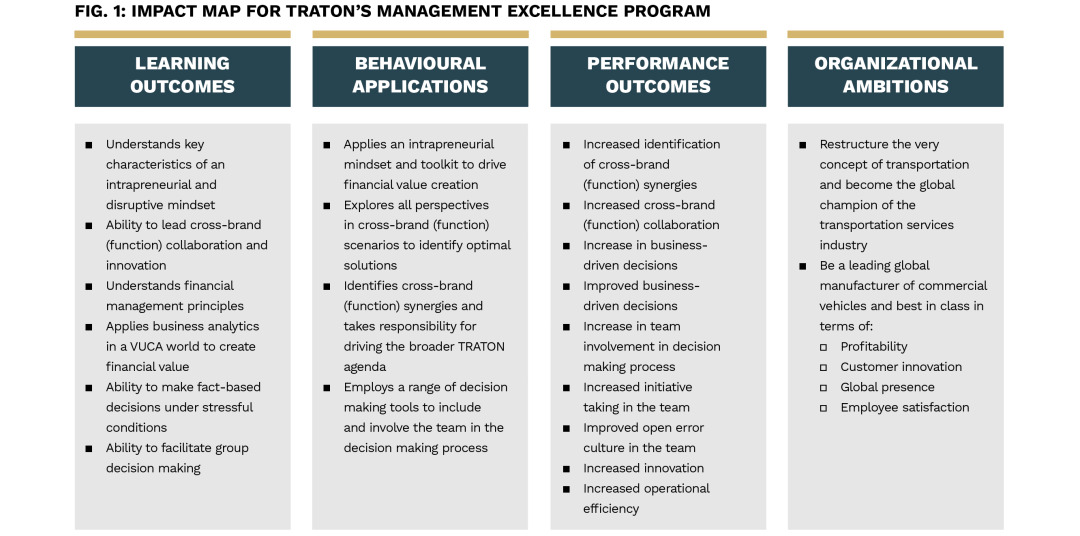

To start, the parties met for a series of workshops to debate and define the value proposition of the initiative, the performance expectations on the participants, and what the content must be to support those performance expectations. After a few iterations – these things take time – the impact map (see Fig. 1) for the program was agreed upon.

Originally conceived by training transfer thought leader Professor Robert Brinkerhoff,1 the impact map provides a one-page overview that shows how the learning intervention will connect to and contribute to business results across four interconnected columns.

Starting on the right, Organizational Ambitions describe TRATON’s high-level strategic goals.

The next column to the left describes Performance Outcomes: these are the more immediate and individual outcomes that are expected to occur as participants use what they have learned. Performance Outcomes bridge the gap between Organizational Ambitions – which appear to be quite distant – and the next column to the left, Behavioral Applications.

Because it is possible to apply everything that one has learned on a training program and still not create one grain of meaningful business impact if that application occurs at the wrong time, in the wrong place, with the wrong person etc., the Behavioral Applications column attempts to define the where, when, and how of application so that the Performance Outcomes will occur.

The last column over on the left, the Learning Outcomes, defines only that knowledge and those skills that support the Behavioral Applications.

The attentive reader will note the impact map is developed in reverse order, starting with desired results on the right-hand side and working back towards the learning outcomes. This ensures a result-focused content and design.

The impact map is a multi-purpose document that is invaluable at several stages of the program design, execution, and follow-up:

Its first job is as dialog tool – it ensures the alignment across various stakeholders on the program logic, the learning intervention storyline, and contribution to business results.

Its second job is the design blueprint. The two left-hand columns – Learning Outcomes and Behavioral Applications – provide guidance on what content to include and which scenarios participants should focus on to use the learning in the most effective ways.

Its third job is as communication tool. Even the best-designed program is unlikely to succeed if the participants and their key stakeholders (e.g., supervisors, team members) are not clued in. The impact map provides a concise way to communicate the purpose of the program and its expectations to program participants and other key stakeholders. Communicating not only the Learning Objectives but also the expected Performance Outcomes and how these relate to Organizational Ambitions creates commitment and buy-in.

Finally, the impact map’s fourth purpose is to provide an evaluation blueprint. If the two left-hand columns provide a design blueprint, then the two right-hand columns – Performance Outcomes and Organizational Ambitions – provide guidance about what should be investigated, evaluated, and qualified as success.

The observant reader will note that we are now quite some way into our article and yet our TRATON Management Excellence example is not yet off the starting blocks. Quite right. When you are designing and evaluating for business results, set the table for success. Make sure all stakeholders are aligned with the targets and how you will measure them. Doing this after the training is like packing your bags, jumping on a plane, and then deciding where you want to go on holiday – it just doesn’t make sense!

Making the shift: from event paradigm to journey paradigm

In recent years, the professional learning and development community reframed learning from an event to a process that requires (amongst other things):

- digestible, bite-size chunks of learning content,

- guided practice over time in scenarios that became gradually more challenging, and

- qualified feedback and support.

The first point is relatively easy to implement – simply take a traditional three-day workshop, break it down into smaller chunks (e.g., a two-hour seminar, a 30-minute e-learning module), and pull it out over time. Voilà, you have a learning journey! But will this deliver the business results defined by our impact map? Most likely not. Without deliberately building guided practice and feedback into the journey, program designers will find most participants ill-equipped to transfer their learning to the job.2 Transferring the learned knowledge and skills to the performance environment requires new behaviors. This can be daunting for the participant and risky for the organization if the experiment goes wrong. Thus, we build in thoughtfully guided practice scenarios in our learning journeys that become gradually trickier and more complex as the journey proceeds. We also consider where feedback will come from, so that our participants have the support and encouragement they need to sustain behavioral change.

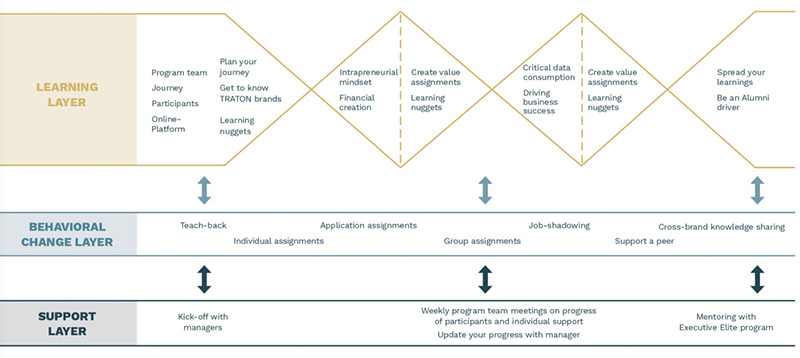

With the impact map in place, the Management Excellence program team set out on a 10-month journey built around a three-layer approach (Fig. 2).

The learning layer was modeled on the design-thinking principle of converging and diverging thinking.

Before each of the synchronous interventions (so-called Labs), participants received a series of assignments designed to build common knowledge foundations (converging).

The Labs then developed these concepts and provided a safe environment to share perspectives and experiment with new skills under guidance of the ESMT Berlin faculty (diverging).

The behavioral-change layer connected learning and impact. The centerpiece of this layer was the application challenges, which offered participants tangible ways to use the skills they had practiced during the Lab. Participants were required to identify, carry out, and report back the three most relevant and valuable challenges for them in their role. This approach built learner autonomy (participants chose their challenges) but also ensured that their application efforts were effective (they chose from an approved, pre-determined list).

The third and final layer was the support layer. This layer leveraged multiple relationships – faculty, program peers, team members, and supervisors – to provide support, feedback, and accountability for the change.

The three-layer design paradigm created a seamless and cohesive 10-month journey that was woven into the very fabric of each participant’s job role.

Don’t hope for results – drive them!

What gets measured, gets done. For decades, learning and development professionals have faced a challenge; even if they wanted to shift their role from “conveyer of wisdom” to “driver of performance improvement,” they found themselves in the dark. How do we know if Johan is resolving team conflicts? How can we find out if Anna is using the feedback model with her team members? Without transparency and insight into the participants’ performance environment, it is practically impossible to track progress as the journey unfolds or to evaluate results.

Using their proprietary online learning platform, the TRATON Management Excellence team uploaded learning nuggets (e.g., case studies, videos, knowledge packs), supported social learning, created participant accountability and, most importantly, tracked the real-time progress of each participant. Using this progress data as input, the program team met once a week to evaluate progress and make decisions to keep it on track, through, for example, sending a reminder to the entire cohort to complete their assignments, offering support to the participant Anna, or messaging the supervisor of the participant Johan.

By systematically checking progress against the impact map, the program team continuously fine-tuned the journey and obtained the envisioned results. At the end of the 10 months, the program team realized that – beyond fulfilling the defined performance outcomes of the impact map – the program had generated an emotional momentum for behavioral change for the participants and their superiors. When winning Gold in EFMD’s prestigious Excellence in Practice Award in 2021, the team felt greatly honored to have their accomplishment recognized… and even more motivated to further improve designing for impact.

About the Authors

Christoph Burger is an affiliate senior lecturer at ESMT Berlin. He joined ESMT in 2003 and worked before in industry at Otto Versand, as vice president at Bertelsmann Buch AG, in consulting practice at Arthur D. Little, and as an independent consultant focusing on private equity financing of SMEs. His research focus is on innovation/blockchain and energy markets. Burger studied business administration at the University of Saarbrücken (Germany), the Hochschule St. Gallen (Switzerland), and economics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (US).

Edward W. Boon works for Promote International as consultant and lead facilitator of the Brinkerhoff Certification for High Performance Learning Journeys program. Based in Stockholm, Sweden, he has nearly 20 years’ experience designing, developing, and delivering soft skills training to international clients. Edward is co-author of Improving Performance Through Learning: A Practical Guide for Designing High Performance Learning Journeys.

Nora Grasselli has been a program director at ESMT Berlin since 2012 and is responsible for the design and delivery of its flagship programs as well as customized programs for corporate clients. Prior to joining ESMT, she worked as a strategy consultant for the Boston Consulting Group and was a lecturer for MBA and executive programs at multiple business schools, including HEC, Oxford Said, Reims School of Management, and the Central European University. Grasselli earned her doctorate in management and organizational behavior at HEC School of Management. Her research has been published in Organization Studies, MIT Sloan Management Review, The European Business Review, and Forbes.

References

- See High-Impact Learning: Strategies for Leveraging Performance and Business Results from Training Investments (Brinkerhoff & Apking, 2001)

- See Improving Performance Through Learning: A Practical Guide for Designing High Performance Learning Journeys (Brinkerhoff, Apking and Boon 2019)