It has been five years since I published the first article on Decoupling theory here in the European Business Review, explaining how, regardless of industry, startups are disrupting markets in a very similar fashion. Since then, I have published more than two dozen articles on the theory, written a best-selling book entitled Unlocking the Customer Value Chain, and advised various companies worldwide including Samsung, American Eagle, BMW, Microsoft, Hyundai, Red Cross, among many others through my firm Decoupling.co. In the interim, I have learned a few important lessons on the power of customer-centric innovation, mapping the customer value chain, and applying offensive decoupling strategies as well as defensive response strategies. In this follow-up article, I describe how companies manage to grow fast after using decoupling as a disruptive entry strategy. The goal is to share best practices and a process for executives and managers interested in implementing a customer value-centric growth strategy.

All around the world, large established companies are worried about being disrupted by startups and are in need of finding new high potential markets to enter and grow. Historically, the standard way of thinking about which markets large companies should enter revolved around the idea of “adjacencies” and “firm-side synergies.” Here is a short explanation on this standard approach to growth in new markets.

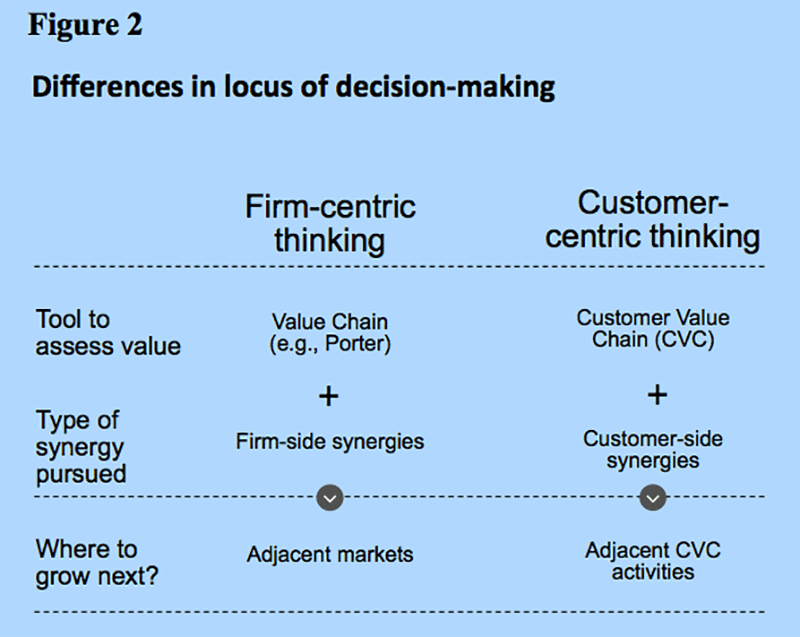

My former colleague, Michael Porter, suggested the value chain in 1985 as a tool to assess where to grow by identifying a firm’s competitive advantage. The late CK Prahalad later introduced the concept of core competencies in the mid-1990s and complemented Porter’s approach. Bain consultant, Chris Zook, then refined the idea of identifying market adjacencies in the early 2000s. Porter, Prahalad and Zook took a firm-centric approach to the question: Which markets to enter and grow? While these approaches have many merits, the downside is twofold. First, it still leaves open the possibility of entry into many—potentially dozens or more—adjacent markets. With so many potential markets for expansion that build on a company’s existing skillsets, it’s difficult to decide which one to pursue. Second, and perhaps most importantly, Porter, Prahalad and Zook focused largely on what would be best for the company versus what would be best for their customers.

While a firm-centric thinking has worked wonderfully in the past, there are new signs pointing at its limited ability to drive fast growth going forward. The reason? My latest research shows that, due to their changing behaviors, customers disrupt markets. By disruption, I mean when startups find ways to steal large amounts of market share from incumbents in a relatively short period of time. They do so by creating products and services that are valuable to customers and enable customers to be acquired more easily. One way to do this is to offer customer-side synergies: new products that, when your customer uses in conjunction with the original product, make it cheaper, easier or faster for them to fulfil their needs as compared to using two (or more) products from different companies to fulfil the same needs.

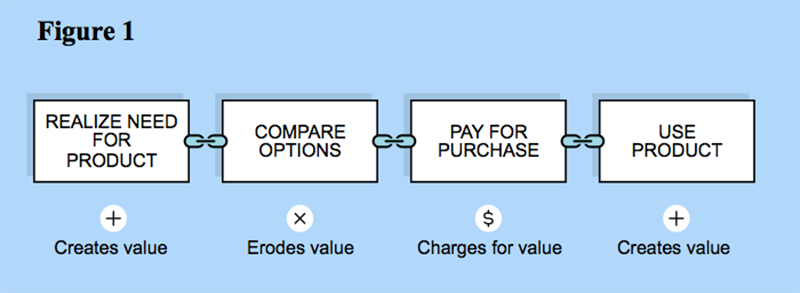

In planning for disruptive growth, firms need to look at all relevant aspects from the point-of-view of their current and potential customers. They should start by looking for new opportunities using the customer value chain, or CVC, which is the sequence of activities that customers execute in order to acquire and consume goods and services. All CVC activities can be uniquely classified into value-creating, value-eroding and value-capturing activities. Figure 1 depicts this in the case of a retail purchase.

In recent years, the focus on innovation and finding growth opportunities has switched from the firm’s perspective (what is best for us?) to the customer’s perspective (what is best for our customers?). As shown in Figure 2, this switch to a customer-centric mindset has profound implications for what strategy frameworks are used, what types of synergies should be leveraged and even which markets to enter.

This customer value-centric thinking was not pioneered by large and established companies. On the contrary, it was adopted first, not by the incumbents, but by their challengers, the tech startups. By 2021, Alibaba had become one of the world’s largest companies by market capitalization, with more than ten multibillion-dollar businesses in wide ranging sectors such as retailing, ecommerce, online cloud services, mobile phones, logistics, payments, content, and more. Between 2011 and 2016, the company’s revenues grew at an average compound annual rate of 87 percent. Profits jumped by 94 percent and cash flow by 120 percent. This rapid growth was quite unique for such a large and established digital company. Yet, Alibaba continues to grow remarkably fast more than 20 years after its founding. How?

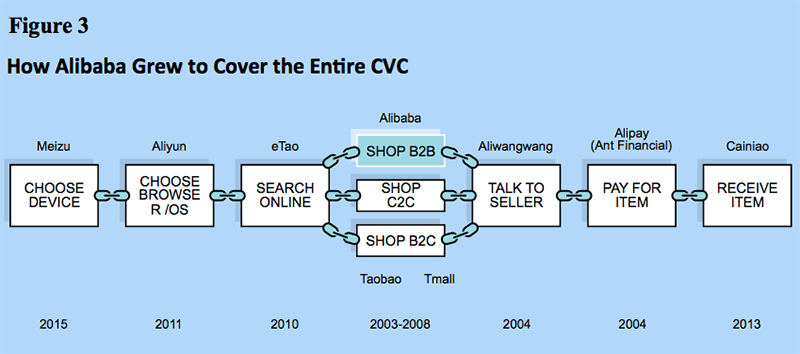

The company was founded in 1999 as an online business-to-business marketplace. In 2003, it moved into consumer-to-consumer ecommerce, and in 2004, built both Aliwangwang, a text message service, and Alipay, an online payments service. The next year, it went on to acquire Yahoo China in an effort to provide consumers with content and web services. In 2008, it launched TMall, a business-to-consumer online retailer. Other new business launches proceeded in turn: a search engine company named eTao (2010), a start-up called Aliyun that created mobile operating systems (2011), and a logistics consortium named Cainiao (2013). In 2015, Alibaba took a majority stake in smartphone maker Meizu.

Note how many of these companies operated in vastly different industries. The synergies between retailing, cloud computing, payments, and electronics manufacturing are not very clear. Businesses in these industries require different resources and employees with widely varying skillsets in order to compete. So why didn’t the company stick with its original business-to-business online marketplace and focus growth where it had a competitive advantage, or move into adjacent industries as prior academics and consultants espoused?

Alibaba’s expansion strategy focused squarely on customer-side synergies around CVC adjacencies. In 2016, around 50 percent of online shopping in China took place via mobile phones, with the rest occurring on laptops, desktops, and tablets. To shop online, consumers first had to decide which device to use to access the internet, and implicitly, which operating system and browser combination to use as well. After that, most consumers opened browsers and pointed at websites, accessing their communication services, email, social networks, chat apps, and so on. At some point, they identified a need to make a purchase and performed searches on search engines or on ecommerce websites. From there, consumers arrived at the most appropriate ecommerce sites. In China, business customers went to Alibaba, while consumers went to Taobao or Tmall. To negotiate prices or terms (a common practice in China), buyers communicated with sellers usually by chat apps. Consumers then had to pay for their purchase and wait for a logistics operator to deliver it. This represented the extent of the typical online shopper’s CVC.

Analyzing this CVC in Figure 3, we spot a clear pattern. Alibaba began growing by focusing on a single stage of the shopper’s CVC with its Alibaba website. It then moved outwards to capture other customers’ activities. Instead of using the traditional industry adjacencies approach (payment, mobile phones, and logistics are not adjacent industries), the company opted to move into adjacent CVC activities. By 2018, the company’s businesses were serving most of the CVC activities. Alibaba didn’t immediately pursue firm-side synergies. Its real win came from achieving customer-side synergies. It opted to deliver benefits to its current customers at each growth opportunity. That, in turn, convinced its customers to couple their activities in a “one stop shop” manner. Eliminating a major obstacle—finding different customers for its new businesses—allowed Alibaba to grow faster.

Implementing Growth by Coupling

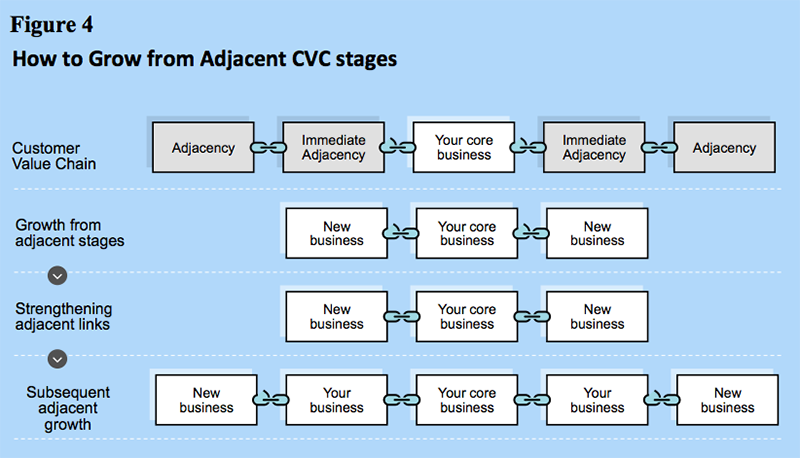

Focusing on customer benefits and growing around their (not your) value chain, a process I termed ‘coupling,’ requires going through the four-step process depicted in Figure 4. First, map out the stages in the customer value chain. Second, identify the immediate adjacent stages of the CVC for which your company does not have offerings. There are generally only two, and they are the first natural candidates to explore. Other proximate, non-immediate, adjacencies are also potential candidates. Third, upon entering these adjacencies with new offerings, make sure to strengthen the links in the CVC by creating customer side-synergies.

For instance, Google started with a search tool. When Gmail came out in 2004, it brought search and email integration together—just one click away. Google Maps, launched in 2005, allowed users to click on an address in Gmail and see its location pop up on a map. A few years later, in 2011, Google Flights allowed users to purchase a ticket, also one click away, with no need to sign in or copy and paste information across websites. Google came to fill all the major adjacencies in a user’s work-related travel CVC by reducing the effort and time previously experienced by having to work with multiple websites. Fourth and lastly, after strengthening the links between stages of the CVC, it is time to grow into stages farther apart from the original core activity.

Coupling activities worked for Alibaba, an innovate tech company. But can it also work for large companies in traditional industries? In short, yes. Ping An is a Chinese insurance and financial services conglomerate. As one of the largest insurance companies in the world, it is in more than 40 different businesses, among them health, life and property insurance, real estate, investment banking and other financial services. So, in 2014, it was not easy for Ping An, a company with revenues of $135 billion, to find other high growth potential markets to enter. In internal discussions, entering traditional market adjacencies was one obvious approach. It could attempt to enter adjacent financial services such as retail banking. Or it could enter an adjacent geography such as Japan or Korea. Alternatively, it could enter an adjacent segment of customers such as high-end insurance. Instead, it chose to focus on what was best for its more than 300 million middle-class customers.

Pin An executives realized that many Chinese did not have health insurance. And those that did, had payment anxiety after going to the doctor, not knowing if and when they would get reimbursed from their health insurance. Therefore, Ping An decided to create an app that helped people pay for their healthcare and get reimbursed from their insurance provider (a CVC adjacent activity). The app quickly took off, and Ping An started adding other functionalities to it such as the ability to schedule a doctor’s appointment and even talk to the doctor remotely. Fast-forward to 2021, Good Doctor is the most widely used app of its kind in China, serving 70 million monthly active users. In April 2018, it was spun out of Ping An, IPOed and raised $1.1 billion dollars at a valuation of $5 billion.

Pursuing a CVC adjacency growth strategy served such a large and established conglomerate well, a hard feat to accomplish in the age where only tech companies and startups can create such high growth. When I visited Ping An’s headquarters in April of 2018, the company was in the last stage of adjacent growth: mapping out all the non-immediate adjacent CVC activities that they could potentially enter with the goal of creating new $1 billion customer value-centric businesses.

The Challenge of Growth by Coupling

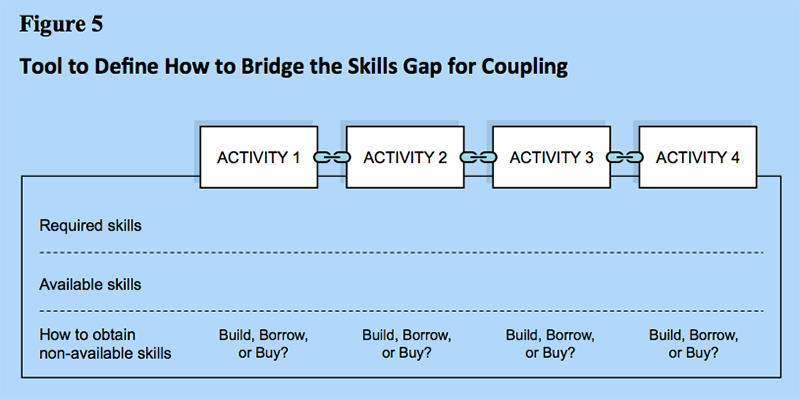

Coupling does not come without its own challenges. The main hurdle of pursuing growth by expanding on the customer value chain is that oftentimes this may lead your company into vastly different businesses that require vastly different people, skills and capabilities than the ones it possesses. In the case of Alibaba, it went from ecommerce to financial services, to search tools, to logistics, to hardware and to software. There are very little common assets to leverage in these businesses. When I present coupling as a growth strategy to my clients, I warn them of this hurdle and ask them to fill out the table in Figure 5 with the skills they think will be required to succeed in a new adjacent activity, whether they have those skills, and, if not, how they plan on obtaining them. Will they build them internally, borrow them from others via new partnerships or buy them through acquisitions or recruitment? What they cannot do is disregard the need to bridge those skill gaps. (The same can be done for technology and other resources).

Today, customers have options. Consequently, the balance of power has switched from sellers to buyers. The implication for executives of established companies, while far from simple to implement, is quite simple to state: companies that want to grow should put the needs of the customer before their own. That entails innovating on behalf of customers, deciding which markets to enter primarily based on how much customer value can be created, and building in customer-side synergies for co-consumption of products and services offered by the company. In short, innovation and growth has to be customer value-centric. I hope this article provides a compelling rationale for executives to move away from a firm-first to a customer-first mindset, as well as showcase a practical step-by-step approach for how they can start this journey.

Customer Value-centric principals to keep in mind

1. Find paths that go in favor of (versus against) your customers’ evolving behavior.

When Amazon decided to move from the books category to electronics, it faced challenges by not having any physical stores (at the time). Therefore, it developed apps that facilitated people to go to physical stores and take pictures, scan bar codes, or search for the price of electronics on Amazon that they wanted to buy. As a consequence, people started showrooming significantly more in Best Buy stores than before. Initially, its executives wanted to prohibit this detrimental behavior to their business. They changed the bar codes of TVs and even considered jamming Wi-Fi signals inside stores. This all went against consumers desires to compare prices online. Eventually, executives realized that if their customers wanted to showroom, then they should let them. Best Buy then went after charging their suppliers for the value they were creating by letting people touch and feel the electronics in the store. The retailer started charging slotting fees in electronics retailing, a practice common only in groceries stores at the time. This solution did not preclude shoppers from showrooming.

2. Abandon your business model if it no longer serves the fast-growing portion of the market.

Executives of established businesses often find it difficult to re-think their business models. Can incumbents viably venture outside their standard offerings? For instance, can an automaker really afford not to make cars for consumers to buy (the standard model in the auto industry)? Actually, yes. Lynk & Co., a joint venture between Sweden’s Volvo and China’s Geely, makes cars specifically for subscription and ride sharing. It charges a monthly subscription to a car that you can buy online and return when you desire. According to their website, “you do not buy, own, maintain, insure, register or take care of anything except for driving.” Why such a drastic departure from the car ownership model? Volvo-Geely executives realized that many of the young consumers at the age of buying their first car questioned the need to own a car and all the hassle and costs associated with the decision. So, the auto maker decided to evolve its business model to cater to this new generation of car drivers (not owners).

3. Take a more expansive view of your opportunities.

Many established companies ‘pigeonhole’ themselves too narrowly in a specific industry. As a consequence, their area for exploring new growth is limited, not by their potential or their capabilities, but by arbitrary industry definitions. The fastest way to grow is to offer something that your current customers, those most loyal to you, would gladly pay for. By virtue of them acquiring this new offering, the original product or service becomes more valuable to them. In other words, new products should have synergies for the customer to adopt as the Ping An case highlights.

Bibliography

- Teixeira, Thales and Peter Jamieson. 2016. “The Decoupling Effect of Digital Disruptors.” European Business Review (July–August 2016): 17–24.

- Teixeira, Thales and Greg Piechota. 2019. Unlocking the Customer Value Chain: How decoupling drives consumer disruption. Ed. Currency, NY,NY. (Translated into Portuguese, Chinese and Korean.)

About the Author

Thales Teixeira is the co-founder of Decoupling.co, a digital disruption and transformation advisory firm. Previously he was a professor at Harvard Business School for ten years. He is a judge at CNBC’s Disruptor 50, a contest of the most disruptive startups in the world. He is the author of Unlocking the Customer Value Chain: How Decoupling Drives Consumer Disruption (Currency, 2019).