Why does management development focus almost solely on the neck up, when the demands placed on managers and executives touch every facet of their lives? In this article the author discusses a design-thinking approach to sustainable leadership.

The designer constructs the world within which he sets the dimensions of the problem space, and invents the moves by which he attempts to find solutions. – Donald Schön

Jordi couldn’t figure it out. He was sleeping well enough. He was exercising without excess. All the boxes were checked. The same habits and routines that had served him so well over the years, and which led to his recent promotion, were in place. But he was exhausted. Ever since he started in his new role, he was finishing each day physically and mentally drained. It had started to cause tension at home, where he was unable to fully participate in family life, and where he was able to recover just enough before starting work the next day.

And it was at the start of that workday where we uncovered the insight that was to re-invigorate his energy and performance. For years his daily commute had been a 35-minute journey on a moped in heavy city traffic. With the increase in quality and quantity of decisions in the new role we identified the issue of decision fatigue1 as being a key factor, with much of that precious decision-making energy being used on a stressful (though accustomed) morning commute. We replaced the moped journey with a scheduled daily private taxi, allowing the executive to spend some free time, arrive at the office relaxed and with decision-making energy at optimum levels. Design thinking was used to re-engineer his day and improve his personal sustainability.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

The business case for executive health

Why does management development focus almost solely on the neck up, when the demands placed on managers and executives touch every facet of their lives? Advanced skills in their profession are often undermined by their novice status in matters related to health and wellbeing, matters which provide the foundations for those advanced skills to flourish. As we progress through a career, we tend to increasingly live our lives on a purely mental level, with all of our emails and strategies and meetings and metrics, forgetting we have a body until something goes wrong with it!

In our work on sustainable leadership, we take a view of the whole person and remind busy professionals that they have a body. Not for better health and well-being but for sustained executive performance, thereby making executive health an actionable business strategy. The Sustaining Executive Performance (SEP) model2 contains actionable common sense that links individual change to the business case at the organisational level and which also fits with wider societal needs. And we are all executives, regardless of job title. The modern-day professional is required to reason, solve problems and plan on a daily basis – executive function tasks carried out on the main by the frontal lobe part of the brain.

There is no shortage of content and messages for health and performance in the workplace – from the seminal Corporate Athlete methodology,3 to the recent tidal wave of mindfulness in the enterprise. Yet content on its own is not enough. We have found that executive health, regardless of the depth and breadth of the knowledge itself, will flounder unless accompanied by a deep consideration of individual context and behaviour change. Changing behaviour is of course a difficult task yet we have found that a design thinking approach can help immensely – in both uncovering the deep lying insights necessary to impact on an executive’s life, as well as locking-in those new ‘designed’ behaviours.

So how may we apply design thinking to the challenges of health and performance in the 21st century enterprise? First, let’s take a step back and look a little closer at design.

What is design?

On a simple level, design is the process whereby something is created. This creative process is followed by some manufacture or elaboration so that the design becomes reality. So design is about doing, quite ironic given the standard worldwide acceptance of the design thinking term. Design cannot be passively learned and so some practice in designing, whether that be through sketching, prototyping, observing or interviewing, is necessary to learn. Although there is freedom within a necessarily creative endeavour, structure and rigour are required for design to work, and to produce the desired end result. Design begins with a brief and follows a creative process, whereby potential solutions or concepts are generated and then evaluated, before the necessary details are elaborated to move that design toward reality.

Although we may argue that design has been part of human activity for millennia in terms of the world that we have created, as a field of science it is only about 60 years old. The birth of design as a research field can be traced back to the 1960s with the creation of the first design models, and the publication of Design Methods, by J. C. Jones in 1970 marked a milestone in moving design understanding to the masses. Basic methods, such as brainstorming and morphological analysis, were formalized and related to an understanding of the process of design. We now highlight three key features:

1. Design is human: Design is, above all things, human. It looks to create a world that satisfies the needs we have as human beings. These could be the products we use, or services we consume, of varying complexity, yet the key is to consider the dynamic nature of those needs which may change during the course of a day, or indeed, life. These needs may also exist on an ‘extreme’ level, of particular interest in design because these extreme needs are often characteristic of lead users, a part of the population who may offer insight into the future because they experience such needs ahead of the general population. Empathy is a key term related to the human nature of design. How may we fully understand the needs of another human being if we have not walked in their shoes?

2. Design is hidden: Such needs may be difficult to articulate, and designers question aspects of our human life that are often difficult to see or appreciate as being necessary to improve. Donald Schön said that “we know more than we can say” and the subconscious part of our brains often drive our actions. Gerald Zaltman, a Harvard professor, has stated that conscious activity represents only 5% of cognition.5 The hidden 95% is therefore the target of design if we want to satisfy human needs.

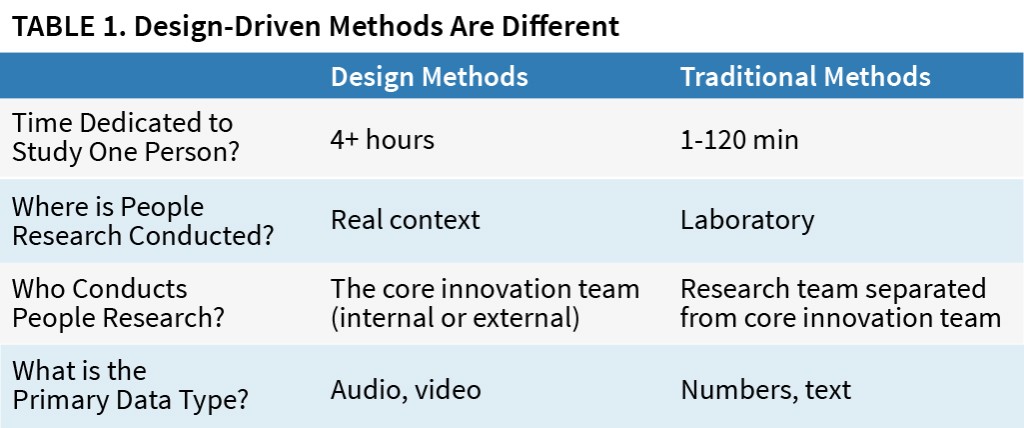

3. Design is enabled through methods: Design is equipped through various tools or methods (see table 1 below), employed at different stages of the process to progress toward an optimum solution. They may be used to understand the user, challenge assumptions, generate concepts, and essentially connect the need, user, and designer. Many of these methods have been taken from other fields including anthropology and engineering, which also relates to the diversity in design. Teams are almost always multidisciplinary and may contain engineers, MBAs, lawyers, and doctors, who pursue a broad, exploratory approach. Although such teamwork may advance within the workplace, methods are designed to enable their implementation in the real context or environment of the user, commonly referred to as the field.

Applying design to executive health and performance

Design trades in insights – the deep-lying, non-obvious, yet often simple pieces of knowledge and understanding that drive next-generation innovations. Ethnographic fieldwork therefore represents a powerful tool in a designer’s armoury. Our own experiences in using the shadowing technique for example, where we observe and interact with people in their real environment, have shown the power of uncovering small yet significant insights in a person’s daily life. And we have taken this same approach to the issue of executive health, such as uncovering the commuting insight that transformed Jordi’s post-promotion performance.

Think about how you spend your own day, by reflecting on a typical design thinking template as shown in Figure 1. How do you spend the minutes and hours of your day? What are the choices you make that drive your executive performance? We believe insights from seemingly innocuous or hidden places, sometimes the insignificant actions that drive the day of the user in traditional design research, could also hold the key to re-engineering the daily habits of the modern professional. If design thinking is so expertly leveraged by global champions such as Apple, BMW, and IDEO, why don’t we turn this deep dive methodology inward? Ironically, this may leverage the sustainable performance of the very executives who approve the projects for the insights to be gained in the first place.

There are five characteristics of design that inform our approach, and which may also serve for any individual to reflect on their own professional life. Since we believe that design cannot be passively learned, we frame these concepts within the need for more practice.

1. Practice more environmental design: The executive environment is the equivalent of the field for the design researcher. We work on the premise that the executive environment has two main elements – the built environment and the social circle. Let us consider a simple example. At work, you want to commit to taking the stairs at every opportunity instead of the elevator. Your immediate environment will ensure you succeed, or fail. Consider your social circle first. Walking along in deep conversation with your colleagues, and you will more than likely be swept along in the usual flow towards the elevator. If you do happen to find yourself alone, the built environment takes over. In the vast majority of office spaces the elevator is the first thing you see, the space being designed to make that the natural choice. The staircase entrance, on the other hand, is usually hidden along a dark corridor. With your mind being full of emails, conversations, and deadlines, being mindful of that staircase entrance – just like taking a step out from your group of colleagues to be the sole stair climber – takes extra effort which is hard to sustain. In our client work we’ve re-designed the environment through simple things like the vending machine to improve workplace eating choices recognising the effect on decisions, more integral workspace design including the staircase and office furniture, and on an individual level, managing expectations through considering the peer group and direct report for the executive in question.

2. Practice more exposure to ambiguity: Experienced design thinkers are comfortable with ambiguity. And in today’s complex professional life, ambiguity is an increasing feature. Although not the same concept we may reference opposing views in business. Whether it be operations and innovation or short-term versus long-term results, senior leaders have long been aware of the need to build an ambidextrous organisation.6 And as stated by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Looking to another recent management methodology, that of Adaptive Leadership,7 managers are encouraged to hold back from rapid definition of a management task in the workplace so as to open up new and fresh possibilities. In a similar fashion, exposing both our professional and personal lives to more ambiguity, though uncomfortable in the short term, may help to uncover new practices and habits that drive superior health, wellbeing, and performance. The next time you’re ready to action on one of your long-held beliefs or values, consider first the exact opposite view. Although you may not follow this opposite view, which may be perceived as a lack of authenticity by your colleagues, it at least opens up a whole range of possibilities and options that may never have been considered before. There is much to be said for being comfortable with being uncomfortable in today’s rapidly changing environment.

3. Practice more observation: We encourage executives to employ a designer’s eye, by reflecting on the rationale on why something exists and attempting to observe a commonly seen view as if for the first time. Mindfulness has been a part of the SEP program since the beginning and most of that is present in a dynamic sense. Mindfulness walks for example allow participants to appreciate the value of silence and the use of their full range of senses. We believe observation to help with mindful practice in general by taking a step back. Day-to-day business is characterised by a close-up view of many problems and we encourage managers to “get on the balcony” for fresh perspective and understanding. With more years of experience we accumulate skills and knowledge and operate to an extent on ‘autopilot’ – a sign of competence. Yet mindfulness in the enterprise is not just about taking time out to meditate, it also regards being more mindful of practice to ensure that autopilot mode still works effectively.

4. Practice more iteration: In design, iteration allows some element of testing to move more rapidly towards a robust solution. In line with some of the personal change commentary on ‘hacking habits’ we encourage an iterative approach to help understand the cause and effect of certain behaviours as well as gain greater comfort with experimentation, change and failure. As long as experimentation (and the failure which often results) takes place in a non mission critical context, just as with conventional innovation projects, this may offer significant value for personal change and development. Put simply, we encourage our executive clients to make small changes to their routines on a continual basis to find out what works for them, seek out things they can do for the first time, and embrace fear.

5. Practice more empathy: Running in the hamster wheel of daily corporate life can de-humanise the best of us. In SEP we emphasise the importance of basic human needs for long-term performance and positive leadership. For example, we trace on several levels the business case of physical movement which helps performance, and highlight the negative effects on human relationships and empathy that result from an irresponsible use of mobile devices. Practicing empathy may come in two distinct areas. First by taking a more holistic view of management to pay attention to the small signals coming from the teams we lead to include more notions of personal care. Noticing, and acting on, excessive weekend e-mail communication, skipping lunch at ones desk or a continual disregard of the importance of sleep may help create high performing teams as well as help fulfill an organisations duty of care. May we also apply empathy inwards? We often coach executives to be more kind to themselves and understand that work doesn’t only need to be about suffering.

Conclusion

Applying design thinking to executive health may reap significant impact. Designing ones’ life, or by considering Stanford Professor Larry Leifer’s 2nd law of design “that all design is re-design” re-designing our life may be achieved by practicing these five simple design features. Design is about finding a better way. Not just a better product or service but a better way of satisfying human needs. So how may we best approach the needs of today’s ‘lead users’ in business – managers and executives in need of improving their sustainable performance? Their needs should not be confined to knowledge acquisition, or even their professional selves, but to become better human beings. Design takes a system level view. Today’s executive life is a complex affair where the boundaries between work, rest and play are blurred and ambiguous. Applying design thinking can help the sustainability of individuals and the teams and organisations that they lead.

About the Author

Founder of The Leadership Academy of Barcelona [LAB] and author of Sustaining Executive Performance (Pearson 2015) Dr. MacGregor has delivered over 1000 sessions the past 5 years in executive health and behavior change for clients including Telefónica, Danone, IESE, IMD, and the BBC. He holds a PhD in Engineering Design Management and has been a visiting researcher at Stanford and Carnegie-Mellon. His executive education teaching is informed by academic interest in sustainability and design and he is an article reviewer for, among others, Industry and Innovation, Journal of Engineering Design, and the International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation.

Founder of The Leadership Academy of Barcelona [LAB] and author of Sustaining Executive Performance (Pearson 2015) Dr. MacGregor has delivered over 1000 sessions the past 5 years in executive health and behavior change for clients including Telefónica, Danone, IESE, IMD, and the BBC. He holds a PhD in Engineering Design Management and has been a visiting researcher at Stanford and Carnegie-Mellon. His executive education teaching is informed by academic interest in sustainability and design and he is an article reviewer for, among others, Industry and Innovation, Journal of Engineering Design, and the International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation.

References

1. S. Danziger, J. Levav, and L. Avnaim-Pesso, “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions,” PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America) vol. 108, no. 17 (April 26, 2011): 6889–6892.

2. S. P. MacGregor, Sustaining Executive Performance: How the New Self-Management Drives Innovation, Leadership, and a More Resilient World (New York, NY: Pearson, 2015).

3. J. Loehr, T. Schwartz, “The Making of a Corporate Athlete.” Harvard Business Review vol. 79, no. 1 (2001): 120–128.

4. J. C. Jones, Design Methods: Seeds of Human Futures (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1970).

5. G. Zaltman, How Customers Think: Essential Insights into the Mind of the Market (Boston: HBS Publishing, 2003).

6. M. L. Tushman and C. A. O’Reilly, Winning Through Innovation: A Practical Guide to Leading Organizational Change and Renewal (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2002).

7. R. A. Heifetz, M. Linsky, A. Grashow, The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009).

[/ms-protect-content]