By Michael Hu and Sunil Chopra

In today’s omnichannel world, the distinction between brands and retailers is of little interest to consumers. They will buy from whoever is best able to “deliver the goods.” Branded manufacturers can take advantage of this unprecedented opportunity to get closer to the consumer, if they manage to acquire the requisite fulfilment and supply chain capabilities.

The Untapped Potential of Branded Manufacturers

Consumers today are spoiled for choice. No matter where they live they have at their fingertips a vast assortment of products, a stunning array of delivery options, and a never-ending parade of novelties, exclusive products, and special offers. The consumer journey is becoming truly frictionless, thanks to advances in digital commerce technologies and disruptive innovations from the likes of Amazon and Alibaba, which continue to push the frontier to enable consumers to buy what they want, how they want it.

What’s more, consumers don’t care who gives them what they’re looking for. Can a retailer deliver the goods? Fine. Is it easier to find and buy what they want from a branded manufacturer? That’s fine too. And, in fact, the lines between retailers and brands are becoming increasingly blurred. Retailers are mimicking branded manufacturers, offering exclusive SKUs and innovative products under their own brand. Amazon, IKEA, and Sainsbury, for example, are investing significantly to expand their private label business. In contraposition, brands are establishing frictionless direct-to-consumer fulfilment options. In many countries across Europe and Asia, online Samsung stores offer products for direct home delivery. Direct-to-consumer is the fastest growing sales channel at L’Oréal and other traditional beauty manufacturers. In the past, retailers tried to discourage – and even thwart – direct sales by branded manufacturers. Today, however, some retailers are actually renting out space where brands can set up a showroom to feature their long-tail SKUs. This tactic, besides allowing retailers to take advantage of surplus space on the sales floor, also enables them to benefit from the brands’ halo effect.

Presently, branded manufacturers’ omnichannel sales – that is, sales fulfilled by the manufacturer, regardless of whether the customer makes the purchase at a third-party retailer, a manufacturer-owned store, or online – typically account for between 5 and 8 percent of total revenue. We believe brands can increase that percentage to between 15 and 25 percent over the next three to five years. Such a shift will not only improve brands’ operating margins, but it will also create greater stickiness with end customers and increase their market power.

Our work helping more than a dozen brands across different sectors such as CPG, Beauty, apparel, and consumer electronics to achieve their full growth omnichannel potential has taught us they must follow a systematic three-step approach to transform their underlying fulfilment capabilities and supply chain:

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Define a clear, segmented fulfilment promise.

Redefine the role of the store, regardless of whether it is an owned store or a rented space at a retail partner.

Evolve the right supply chain partnerships.

Define a Clear, Segmented Consumer Promise

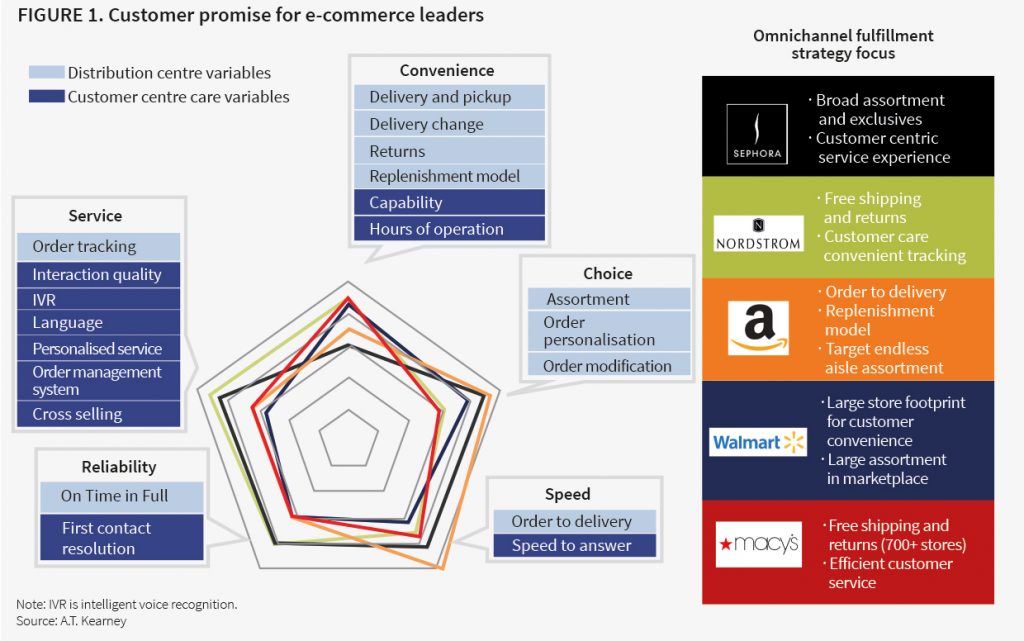

A first step to designing a winning supply chain is to define the consumer promise along five dimensions of fulfilment: choice, speed, convenience, service, and reliability. Omnichannel leaders, particularly retailers, do this well (see figure 1). Mass retailers that sell commoditised products and have relatively low basket sizes – Amazon, for example – tend to focus on a broad assortment, convenience, and speed. In contrast, specialty retailers such as Sephora – where basket sizes often exceed $75 and products are differentiated – usually focus on high customer service and a broad, personalised assortment, whereas speed tends to be less important.

Following the lead set by retailers, when brands define their consumer promise they should consider factors such as how differentiated their products are, how much information the consumer needs to make a choice, and what the average basket size will be. Luxury fashion or beauty brands, for example, offer expensive, differentiated products. Therefore, their customers will likely be more interested in service (for example, call centres staffed by skilled, well-trained agents) and choice (say, an exclusive assortment, coupled with personalised gift-wrapping or engraving) than in speed and convenience. In contrast, brands that sell higher-volume, less differentiated commodity products such as consumables and mass consumer electronics will probably want to excel in speed and convenience, as shopper behaviours have been shaped by Amazon’s offer of fast, inexpensive delivery and hassle-free returns.

Whatever consumer promise the brand settles upon will largely dictate the supply chain it needs.

Redefine the Role of the Store

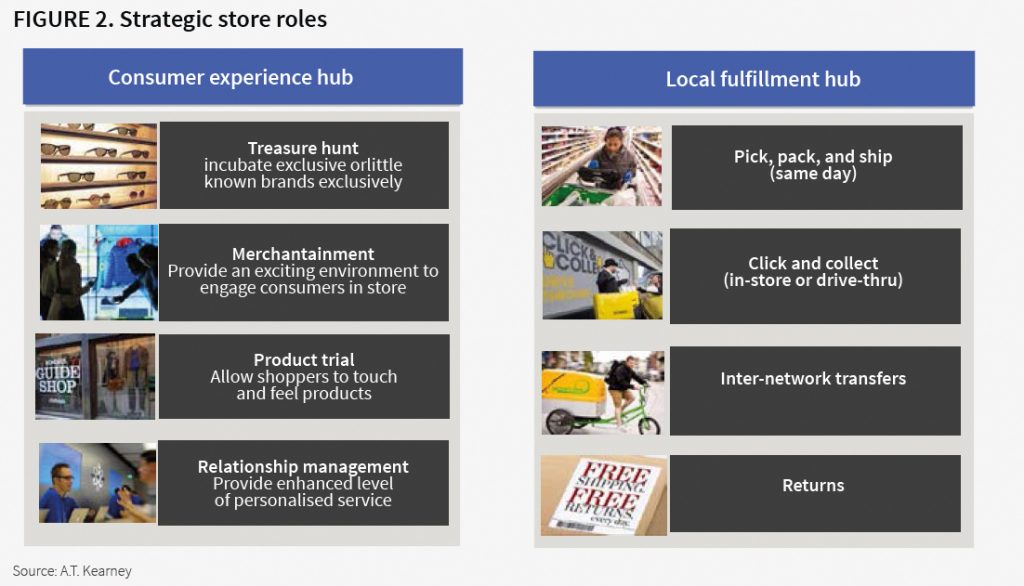

The second step is to redefine the role of the store in fulfilling the consumer promise. Roughly speaking, the store can serve two strategic roles (see figure 2):

The store can be a consumer experience hub where the brand displays its products, lets customers touch and feel them, and offers advice. In the case of relatively expensive fast-moving products for which consumers also value speed – for example, high-end smartphones – consumer experience hubs also stock inventory for sale to walk-in customers. Apple Stores, with their Genius Bar, are a prime example of a consumer experience hub. So are Bonobos Guideshops, staffed by onsite style advisers.

Alternatively, the store can be an inventory and fulfilment hub – a staging area, if you will – to cover local demand. The primary role of such a store has been to carry inventory that customers can purchase when they walk in. These stores can also serve as pickup locations for click-and-collect customers and accept returns of online orders. In some instances, personnel at fulfilment hub stores may also pick, pack, and ship orders. Mass retailers Walmart, Debenhams, and Quelle’s are working hard to convert their store network into scalable fulfilment nodes.

The capabilities and processes needed to deliver a world-class in-store consumer experience are radically different from those required in a fulfilment-focussed store. In a consumer experience hub, sales associates must be knowledgeable and consumer-oriented, technology must be focussed on facilitating the sale, and a deep assortment must be attractively displayed. Stores meant to provide same-day/next-day fulfilment of online orders, in contrast, require a broad range of traditional warehouse and distribution centre capabilities adapted to a store environment, including efficient backroom and shelf order picking, integrated order management systems, assortments skewed to fast-moving items (to satisfy in-store pickup and local shipping), and operationally savvy store managers. It is crucial, then, to understand the role of each store along the experience-fulfilment spectrum to ensure that the proper blend of store operational capabilities, processes, and incentives is in place.

Equally important is the strategy to scale up the store network. Owned stores are one option. Owned stores provide a brand with nearly complete freedom to choose locations and design its own store concept and space. The trade-off, however, is that building an owned-store network is a slow, capital-intensive process.

Another option is to partner with retailers, taking advantage of the fact that retailers with large, physical store footprints are shifting their strategy. In the future, many high-traffic locations will likely become inventory-light consumer experience and showrooming hubs displaying a broad assortment of items available for same day/next day home delivery, while low-traffic locations will either be closed or converted into “dark-store” fulfilment centres. As future retailer showrooms carry less inventory, floor space will be freed up and retailers may be open to establishing branded stores-within-stores for synergistic showrooming. For example, a shopper might be able to walk into a Debenhams’s store, examine and order a suit at a Hugo Boss digital showroom, arrange for delivery to a Debenhams’s closer to home, and have it altered by Debenhams’s in-house tailoring staff at the time of pickup. In the case of lower-traffic fulfilment centre stores, retailers could potentially lease them to brands for joint use. For example, Walmart could convert select suburban superstores into shared warehouses to stage inventory for local delivery, powered by an easy-to-use order management system. Brands could then lease the “Walmart platform” to scale up a same-day/next-day delivery option across the country.

Evolve the Right Supply Chain Partnerships

Omnichannel fulfilment is a complex orchestration of capabilities that span a broad spectrum: teaches picking, warehousing, store operations, customer service, financial services, and last-mile delivery, to name just a few.

Fortunately for brand manufacturers, a robust third-party omnichannel fulfilment vendors market is available to provide them with the capabilities they need to quickly get started (see figure 3). Such vendors fall into two broad categories:

End-to-end generalists typically have experience providing the full suite of turnkey fulfilment operations. Their capabilities are usually best-in-class in one or more functions, but not across the entire fulfilment spectrum.

Best-of-breed specialists focus on a particular subset of fulfilment services such as distribution centre fulfilment or customer care. Nearly all best-of-breed vendors have more scale and experience in their areas of specialisation than their end-to-end counterparts.

Our experience suggests that companies should evolve their omnichannel fulfilment along the make-versus-buy continuum – beginning with end-to-end outsourcing, continuing with best-of-breed partnerships, and ending with in-house management – as they climb the scale and experience curve. Yet often that is not the case.

Some make the mistake of investing heavily in-house from the outset and miss out on the opportunity to learn from external vendor capabilities. For example, a leading US retailer built its own large online fulfilment centre to anticipate significant e-commerce growth with a three- to four-day lead time. Because of its limited experience with online operations, the retailer created a high-throughput facility with limited flexibility. When actual growth fell short of forecast, that lack of flexibility prevented the retailer from modifying the layout to improve its order cycle time.

Others make the mistake of leaving their operations outsourced for too long to a turnkey, end-to-end vendor instead of transitioning to best-of-breed operators. To illustrate, a well-established US fashion brand, despite having grown its online sales to more than $300 million, continues to use the same end-to-end fulfilment provider for its warehousing, store fulfilment, customer service, and integrated order management operations. As its omnichannel business has grown, the fashion brand has failed to achieve the expected cost savings from increased scale, in part because its turnkey partner lacks the ability to provide world-class service and efficiency in every part of its operations.

To sustain best-in-class omnichannel performance, a brand’s omnichannel supply chain partnership model must evolve over time. The model must adapt to accommodate new strategic directions (such as entering a new product category or a new geographic market) and to reflect the brand’s own growing capabilities. In the first instance, brands need to build a dedicated omnichannel supply chain team. This team will be the nucleus of a centralised, coordinated function to define and sustain in-house operations and to help shape the upstream business and commercial strategy. Eventually, brands will want to establish strong capabilities to internally oversee the underlying order management, inventory, and CRM systems – as these technologies are the main enablers of flexible, efficient operations that deliver a seamless consumer experience. In addition, brands need to periodically conduct rigorous sourcing events to ensure they are benefiting from the latest advances in fulfilment practices.

This is particularly important in last-mile delivery and customer care, where technological advances are rapidly changing the art of the possible.

Keeping Up with the Consumer

In today’s omnichannel world, the distinction between brands and retailers is of little interest to consumers. They will buy from whoever is best able to “deliver the goods”. Branded manufacturers can take advantage of this unprecedented opportunity to get closer to the consumer, if they manage to acquire the requisite fulfilment and supply chain capabilities. The stakes have never been greater.

[/ms-protect-content]About the Authors

Michael Hu is a Principal in the Operations Practice at A.T. Kearney. His area of expertise is helping global consumer and retail clients in areas of omnichannel and eCommerce operations, supply chain transformation, and digital transformation.

Michael Hu is a Principal in the Operations Practice at A.T. Kearney. His area of expertise is helping global consumer and retail clients in areas of omnichannel and eCommerce operations, supply chain transformation, and digital transformation.

Sunil Chopra is the IBM Distinguished Professor of Operations Management at the Kellogg School of Management. He has co-authored two books and several academic articles that have appeared in top journals. His book on Supply Chain Management was awarded the best book of the year by the Institute of Industrial Engineers (IIE). His recent research has focussed on risk management and omni-channel distribution in supply chains.

Sunil Chopra is the IBM Distinguished Professor of Operations Management at the Kellogg School of Management. He has co-authored two books and several academic articles that have appeared in top journals. His book on Supply Chain Management was awarded the best book of the year by the Institute of Industrial Engineers (IIE). His recent research has focussed on risk management and omni-channel distribution in supply chains.