By Adrian Furnham

Counterwork behaviours – CWBs – include fraud, misconduct, and work avoidance cost organisations billions every year. In this article, Professor Furnham discusses the psychology behind CWBs, and how an organisation can reduce instances of counterwork behaviours.

People nick stuff at work. They take part in “the unauthorised appropriation of company property for personal use, unrelated to the job”. They steal from their employer, their boss and their customers. It is all too common and can be costly.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]We have a range of words to disguise the issue: pilfering and shrinkage, nicking and liberating stuff. Many people think that taking home a few pens and envelopes doesn’t count.

There is a long list of what are called ‘counterwork behaviours’ (CWBs). They include deceit, espionage, fraud, sabotage, substance abuse and whistle-blowing. There are, for the politically correct, other things such as ‘low personal standards’, ‘work avoidance’ and ‘indolence’.

CWBs include

• Antisocial behaviour; usually restricted to the workplace.

• Blue-collar crime; everything from theft, property destruction and record fabrication to fighting and gambling by semi skilled, often non salaried staff.

• Counterproductive Workplace Behaviour; any behaviour at work that goes counter to the short and long term interests and success of all stakeholders in an organisation.

• Dysfunctional Work Behaviour; intentional, unhealthy behaviour that is injurious to particular individuals who do it either to themselves or to others.

• Employee Deviance; unauthorised but intended acts that damage property, production or reputations.

• Employee Misconduct; the misuse of resources, from absenteeism to accepting backhanders.

• Non-performance at Work; both not performing that which is required, while also performing acts not at all desirable.

• Occupational Aggressive Crime Deviance; negative, illegal, injurious and devious behaviours conducted in the workplace.

• Organisational Misbehaviour; behaviour that violates societal and organisational norms.

• Organisational Retaliative Behaviours; this is deliberate organisational behaviour based on perceptions of unfairness by disgruntled employees.

• ‘Political’ Behaviour; self-serving, non-sanctioned, often illegitimate behaviour aimed at people both inside and outside of the organisation.

• Unconventional Work Practices; simply odd and unusual, but more like illegal and disruptive, behaviours.

• Workplace Aggression, Hostility, Obstructionism; personally injurious behaviours at work.

• Unethical Work Place Behaviour; behaviour that deliberately and obviously infringes the accepted ethical/moral code.

Academics have tried to classify these misbehaviours into various categories: intrapersonal (drink and drugs), interpersonal (physical and verbal aggression), production (absenteeism, lateness), property (theft, sabotage, vandalism) and political (whistle-blowing and deception).

The term Counterproductive Workplace Behaviour (CWB) is often used synonymously with anti-social, deviant, dysfunctional, retaliative and unethical behaviour at work. It costs organisations billions every year and many of them invest in ways to prevent, reduce or catch those who are most likely to offend. There are many different words to describe CWBs, such as: organisational delinquency, production and property deviance, workplace deviance. It is a multi-faceted syndrome that is characterised by hostility to authority, impulsivity, social insensitivity, alienation and/or lack of moral integrity. People feel frustrated or powerless, or unfairly dealt with, and act accordingly.

CWB, however, is intentional and contrary to the interests of the organisation. CWB may not, in the short term, be reflected in counter-productivity which is the ultimate cost of CWBs. The essence of a CWB is wrongdoing. Thus, taking sick leave when not sick may be a common occurrence, indeed the norm, yet it is still a CWB.

Cheats at Work

In a series of books and papers the anthropologist Gerald Mars showed that much cheating at work was a consequence of how jobs were organised. His initial focus was on the sorts of ‘rewards’ people get at work. These he divided into three categories: official, formal rewards, both legal (wages, overtime) and illegal (prostitution, selling drugs); unofficial, informal, legal (perks, tips) and illegal (pilfering, short-changing) rewards; and alternative, legal, social economy rewards (barter) and illegal rewards (moonlighting).

When people cannot easily increase their formal rewards at work they may try to increase the other two types of reward, which may then come to contribute significantly to their total income. Further, it is the nature of the job that dictates the number and type of informal and hidden rewards.

Thus, in the hotel and catering industry, waiters will receive basic and formal pay in the form of wages and overtime payments. This will be supplemented by informal rewards of tips and the perks of ‘free’ meals and possibly ‘free’ accommodation. They may well also be allowed to indulge in pilfered food or be afforded a ‘winked-at-facility’ to short-change or short-deal customers.

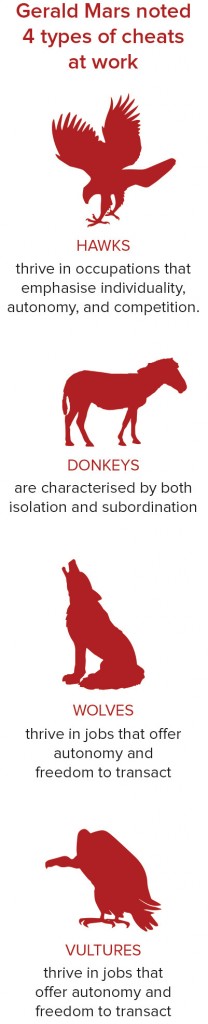

Mars noted four types of cheats at work. First Hawks, who thrive in occupations that emphasise individuality, autonomy, and competition. The control that members have over others is greater than the individual’s own control. Occupations for hawks emphasise entrepreneurial behaviour, where the individual’s freedom to transact on his own terms is highly valued. Individual flair is at a premium. Success is indicated by the number of followers a person controls. Rewards here go to those who find new and better ways of doing things and where the drive for successful innovation is paramount. Hawks are individualists, inventors, small businessmen. They are hungrily ‘on the make’.

Mars noted four types of cheats at work. First Hawks, who thrive in occupations that emphasise individuality, autonomy, and competition. The control that members have over others is greater than the individual’s own control. Occupations for hawks emphasise entrepreneurial behaviour, where the individual’s freedom to transact on his own terms is highly valued. Individual flair is at a premium. Success is indicated by the number of followers a person controls. Rewards here go to those who find new and better ways of doing things and where the drive for successful innovation is paramount. Hawks are individualists, inventors, small businessmen. They are hungrily ‘on the make’.

Hawks are typically entrepreneurial managers, owner-businessmen, successful academics, pundits, the prima donnas among salesmen and the more independent professionals and journalists. Hawkish entrepreneurial activity is also found in waiters, fairground buskers and owner taxi drivers. Alliances among hawks tend to shift with expediency and a climate of suspicion is more common than one of trust. They are loners, individualists.

Second, Donkeys are characterised by both isolation and subordination. Donkeys are in the paradoxical position of being either or both powerless and powerful. They are powerless if they passively accept the constraints they face. They can also be extremely disruptive, at least for a time. Resentment at the job’s impositions on the employee is common and the most typical response is to change jobs. Other forms of ‘withdrawal from work’, such as sickness and absenteeism, are also higher than normal. Where constraints are at their strongest, sabotage is not infrequent as a response, particularly where constraints are mechanised.

Third, Wolves, who thrive in those ‘traditional’, rapidly disappearing working-class occupations, such as mining. Wolves are found in occupations based on groups with interdependent and stratified roles, for example garbage collection crews, aeroplane crews and stratified groups who both live and work in ‘total institutions’ such as prisons, hospitals, oil rigs and some hotels. Where workers do live in or close to the premises in which they work, group activities in one area are reinforced by cohesion in others. Such groups then come to possess considerable control over the resources of their individual members. Once they join such groups, individuals tend to stay as members.

Fourth, Vultures. Vultures are found in jobs that offer autonomy and freedom to transact, but this freedom is subject to an overarching bureaucratic control that treats workers collectively, and employs them in units. Workers in these occupations are members of a group of co-workers for some purposes only and they can act individually and competitively for others. They are not as free from constraint as hawks, but neither are they as constrained as donkeys. The group is also not as intrusive and controlling as the wolf packs.

Vulture jobs include sales representatives and travellers of various kinds, such as driver-deliverers, linked collectively by their common employer, common work base and common task, but who have considerable freedom and discretion during their working day.

These different types of cheats at work form their own ideology, view of the world and values. They make sense of their particular situation and their values then follow from this. Thus wolves value control, discipline and order. Hawks value autonomy, freedom and independence. Vultures tend to be suspicious outsiders.

The crucial point that Mars is making is that the job itself largely dictates what sort of corrupt behaviours are possible and preferred. Further, that some of these are done effectively in groups with co-ordinated team work.

Justice at Work

Many CWBs can be seen as a form of restorative justice: getting one’s own back on various individuals or institutions. People do not all have similar codes of justice; and they can differ in the sensitivity and reactivity to injustice. Nevertheless, one of the most constant, powerful and persuasive reasons people give for vengeful counter-productive behaviours at work is to re-establish distributive justice. Certainly the concept of fairness is at the heart of much dark-side CWB. People can feel it is fair to steal to compensate them for their inequitable pay; sabotage ‘pays back’ others for what they did.

If people believe they (their parents, group, ancestors) have been unfairly treated (their land taken away; their mobility blocked; victimised generally) they are motivated to correct the balance and restore justice. Justice restoration can occur via propaganda or force or CWBs. It may involve punishing the perpetrators or their heirs or simply changing the balance of things. Thus if your land was ‘stolen’ the motive to get it back will drive people to various acts until that is achieved. Inevitably people perceive the just or unjust situation very differently, furthermore some restitution acts are driven by guilt where people see their (privileged) position as being unfairly acquired (say through inheritance).

Justice, fairness, honour, rights and reconciliation are the motives here. The more these words occur in the speeches, writings of individuals or groups the more the justice-motive should be considered important. As we shall see people have used equity theory to explain theft as sabotage at work. Certainly the concept of justice and fairness which is at the heart of equity theory is for all people a powerful motivator. Being thought of as unfairly treated is a primary motivator to achieve revenge.

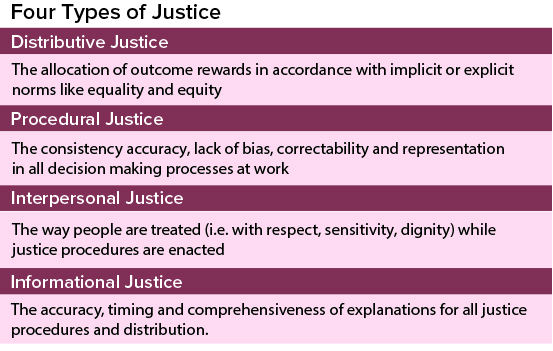

More than any other cause of ‘misbehaviour’ at work, is the issue of people feeling unfairly dealt with and taking vengeance for, or trying to restore justice in the face of injustice. Case after case of ‘insider dishonesty’ cites Fairness. Researchers in this area called Organisational Justice have, for 40 years, done research on the economic and socio-emotional consequences of perceived injustice. In doing so, they have distinguished between four related types of justice:

Although there are, or should be, general context-independent criteria of fairness, there are always special cases. All employees are concerned with interactional justice, which is the quality of interpersonal treatment they receive at the hands of decision-makers. Two features seem important here: social sensitivity, or the extent to which people believe that they have been treated with dignity and respect, and informational justification, or the extent to which people believe they have adequate information about the procedures affecting them.

Procedures matter because a good system can lead people to take a long-term view, becoming tolerant of short-term economic losses for long-term advantage. Research has demonstrated many practical applications or consequences of organisational justice. Using fair procedures enhances employees’ acceptance of institutional authorities. Further, staffing procedures (perceptions of fairness of selection devices) can have pernicious consequences.

People at work often talk of particular types of injustice: unjustified accusation/blaming; unfair grading/rating and/or lack of recognition for both effort and performance; and violations of promises and agreements.

A number of factors relate to people’s reactions to injustice. These include the perception of the motives/state of mind of the wrong doer (did they do it intentionally and with foresight of the consequences). Also, the offender’s justification and apologies play a role along with how others reacted to the unjust act. The relationship between the harm doer and the victim is also important as is the public nature of the injustice. Victims of injustice want to restore their self-esteem and ‘educate’ the offender. Usually they retaliate by either withdrawal or attack. What is clear however is that people’s perception of fairness and justice at work is a powerful motivator and demotivator and often a major cause of negative retaliation behaviours.

There have been studies that have examined employee ‘revenge’ as a consequence of what they see to be unjust behaviour. In one American study the authors were interested in what predicted workers to complain that they had been ‘wrongfully’ terminated after being laid off. They hypothesised that how fairly workers felt they had been tested during the course of their employment and in the termination predicted the type of complaint they made. In addition they tested such claims because complaining is related to the perception that termination of employment is the employers fault. Further that the relationship between complaining and blaming is stronger in those fired rather than merely laid off. Their study showed that three factors were directly relevant to whether people considered they would complain: fair treatment at termination, their expectation of winning the case, and their perception of fairness/justice while at work.

They agreed that the results of this study which involved interviewing 996 employed adults has clear practical implications for all organisations which include: Treat employees fairly throughout their employment and foster the impression that the organisation is interested in justice (procedural and distributive); When terminating people be honest and treat them with dignity and respect; Being honest about the causes of unemployment results in a legal saving of around £10,000 per person; The dignity and self-respect of those terminated can be enhanced by such things as providing transitional alumni status, symbols/gifts of positive regard and offers of counselling; Attempts at litigation control through lobbying and particular settlement practices have only limited success.

So what to do

Consider the common problem of theft. Researchers in the area recommend the following.

First, let people know how uncommon it is. It is NOT the norm: everybody is not at it. It is a minority who fiddle like this. Give some statistics. Thieves, for that is what they are, are the exception and a group that will not be tolerated.

Second, explain the consequences of being caught with some ‘case studies’, but do not go over the top. Spell out the first warning to sacking sequences. Beware the possibility of unintended consequences where making the punishment so severe that it simply makes people take bigger risks with the amounts they claim.

Third, explain the systems and methodology by which people are caught. Let them know that there are reliable and fair methods in place that will show up those trying to beat the system.

Fourth, conduct a few in-house programmes where employees at all levels discuss the company’s code of ethics and how, when and why fraudsters should be dealt with. Get all people involved: let them know the fraudsters are costing everyone who works for the company.

Fifth, review compensation and benefit programmes that look at internal and external equity meaning how people ‘stack up’ against others in the organisation as well as those working in similar jobs in different organisations. Don’t allow expense fraud to be seen as a way of reconciling proper pay differentials. Some supervisors turn a blind eye to it because they feel unable to reward staff in ways they think equitable and just.

About the Author

Adrian Furnham is Professor of Psychology at University College London. He has lectured widely abroad and held scholarships and visiting professorships at, amongst others, the University of New South Wales, the University of the West Indies, the University of Hong Kong and the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and in 2009 was made Adjunct Professor of Management at the Norwegian School of Management. He has written over 700 scientific papers and 57 books including 50 Psychology Ideas you really need to know (2009) and The Elephant in the Boardroom: The Psychology of Leadership Derailment (2009). Professor Furnham is a Fellow of the British Psychological Society and is among the most productive psychologists in the world.

Adrian Furnham is Professor of Psychology at University College London. He has lectured widely abroad and held scholarships and visiting professorships at, amongst others, the University of New South Wales, the University of the West Indies, the University of Hong Kong and the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and in 2009 was made Adjunct Professor of Management at the Norwegian School of Management. He has written over 700 scientific papers and 57 books including 50 Psychology Ideas you really need to know (2009) and The Elephant in the Boardroom: The Psychology of Leadership Derailment (2009). Professor Furnham is a Fellow of the British Psychological Society and is among the most productive psychologists in the world.

References

- Furnham, A. (2014). Backstabbers and Bullies. London: Bloomsbury

- Furnham, A. & Taylor, J. (2011). Bad Apples. Basingstoke:

Palgrave MacMillan - Greenberg, J. (1993). Stealing in the name of justice: Informational and interpersonal moderators of theft reactions to underpayment inequity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54, 81-103.

- Mars, G. (2006). Changes in Occupational Deviance. Crime, Law and Social Change, 4455 (4), 283-296.

- Mars, G. (1984). Cheats at Work. London: Unwin.