By Guido Stein & Manuel Gallego

Introduction

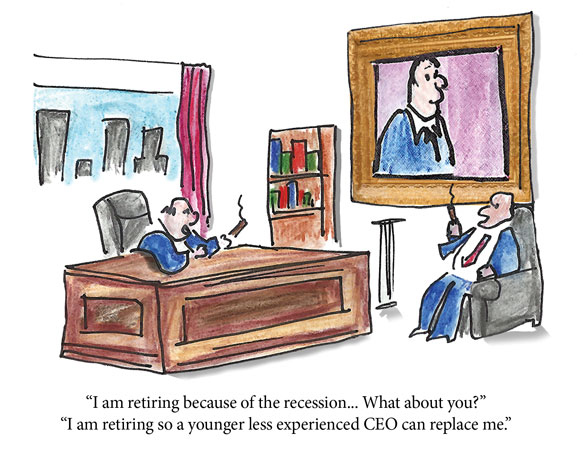

Companies statistically dismiss twice as many CEOs in bad economic times as in good. Certainly, many senior executives have lost their jobs lately. Yet this new wave of dismissals masks a deeper trend: in the past two decades, the average tenure of a CEO has halved, and yet, in less than a third of the cases, the reason for their departure was solely because of poor performance.

Why the increased turnover at the top? In the past, nine times out of 10 the answer was simple: companies hire a new CEO because the old one retired, fell ill or died. Nowadays the proportion has almost reversed: a bit more than 10 per cent is due to natural reasons, the rest lies on decisions taken at the top.

This article deals with those decisions. The sources and insights come from the author´s personal contact with more than 400 CEOs who have participated in the International Advanced Management Programs that he teaches at IESE, his work as consultant and board member, and his research in this field. The empirical data analyzed is taken from 184 CEO of the largest Spanish listed companies between 2001 and 2010. According to the literature the conclusions can be considered generally representative of all western countries. The author is currently confirming these findings in the German speaking economies.

Mapping the territory

Contrary to popular wisdom, bad results are not the main reason that the managing directors of large companies lose their jobs. Although poor performance makes them more vulnerable to being sacked, other factors have to be considered in order to understand the dismissal of CEOs, such as the power they wield within the organization, the availability of alternative candidates and the board’s expectations and loyalty.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]In fact, CEOs most frequently lose their jobs as a result of mergers and acquisitions, through planned succession or because they retire. According to the research, 47 percent of Spain’s listed companies have changed their CEO once or more than once during the period covered by the study, above all in 2009 and 2010, and in particular in the real estate, finance and energy sectors. However, there has been hardly any turnover in the leisure and hotel sector.

What leads a board of directors to dismiss their top executive? What are the factors underlying a CEO’s departure? The reasons may be either endogenous, in which case the executive may exercise a certain influence, if he or she has a capital investment, or is involved in recruitment of directors or compensation; or exogenous such as, for example, age, the type of industry or the size of the company, these are factors over which the executive will have less influence.

Fluctuating turnover: reasons for dismissal

We discovered that more than half (53 percent) of companies kept their managing director in the job during the entire period and almost a third (33 percent) only changed the top executive once during this period. Only 10 percent changed their CEO twice and just fewer than 4 percent had three or more CEOs during this period. This means that barely 14 percent of companies account for the majority of the 123 dismissals recorded during that decade. One practical consideration points to the corporate impatience of some companies with their CEOs.

Curiously, the trend was reversed during the last few years studied. While 2009 was the most active of the decade, with 15 percent of dismissals, 2010 was much quieter and only produced 6 percent of the total CEO turnover. The reasons given for dismissal are those published in the media and other complementary sources of information such as corporate governance reports from each of the companies. This, however, has its limitations. On one hand, because there may be more than one reason for the dismissal, and on the other, because companies don’t always make public the real reason for dismissing someone.

When the reputation of the company or people involved in the dismissal is at stake, they usually offer “generic” explanations, such as personal reasons or some type of illness. At other times, part of the CEO’s severance terms may include maintaining the appearance that he or she has resigned for personal reasons rather than attribute it to the board of directors. Transparency in this area is limited.

The principal causes of CEO turnover are mergers and acquisitions (29 percent in the case of Spain), especially those that result from hostile takeovers. When a company is bought or absorbed by another, the stronger of the two always imposes its management team.

Then there is natural turnover, which represents almost a third of the total. This includes planned successions (19 percent) and retirement (11 percent). It makes sense that turnover through retirement should be high given that a CEO is at the summit of his or her professional life, having arrived at a point where they are able to put their experience to use after a long and fruitful career.

By planned succession we mean the process through which the CEO, along with the company’s board of directors, plans their departure in advance and choose a successor with the potential and skills necessary to take on the job. This can be done through adopting a relay succession strategy, seeking an heir apparent or through staging a “horse race.”

It is interesting to note that in almost two out of every 10 cases, CEO departure has occurred through planned succession. This may be a positive result of improved management and the reforms introduced based on recommendations in the code of good governance.

23 percent of dismissals are directly related to the managing director’s successful or poor performance. In 9 percent of cases, a job well done translates into taking on a more prestigious position at another company, while 7 percent have been fired on the grounds of poor results, the same percentage as those leaving because of disagreements about management policy. In other cases, personal or health reasons are given for the CEO’s departure (8 percent) and to a lesser extent, death (3 percent) and scandal (3 percent). Finally, it should be pointed out that only 2 percent of companies offer no public explanation for the dismissal.

As we have pointed out, poor results are a relatively minor cause of the dismissal. However, these dismissals often attract a lot of media attention, as do those concerning scandal, creating the impression that these are much more frequent motives for dismissal than they really are when the most common reasons are mergers and acquisitions, a planned succession, retirement or moving on to a more prestigious position.

Banking and the real estate sector

The sectors that have seen the highest turnover are financial services and real estate, with 23 percent, followed by consumer goods (19 percent), the basic materials sector, industry and construction (18 percent). The service industry is in fourth position at 16 percent. The sectors with the lowest turnover are energy (13 percent) and technology and telecommunications (around 9 percent).

Is age an issue?

Age itself need not be grounds for dismissal, always assuming the CEO maintains his or her abilities and is capable of carrying out his or her work normally. However, some companies include contract clauses that set an upper age limit for executives. According to our study, the average age of a CEO on departing their post is 62 but there is a variation of 11 years on this figure, in that we have found directors who have stayed on till the age of 90 and others who have left at barely 40. Data on the age of incoming CEOs is more homogenous: around 30 percent take up the position aged between 50 and 55.

The study reveals that CEOs face shorter and more intense mandates. It remains to be seen whether this phenomenon represents a passing fashion or a more fundamental change and whether this increased turnover has been triggered by a higher degree of activism on the part of shareholders. The average tenure in the States since the beginning of the nineties has dropped from 8 to less than 5 years, now we are approaching on average a 3-year tenure. The implications for the daily management of the companies are crystal clear: strategies are designed for the short run, even for the quarter that is the span of time pondered by many investors and theirs analysts.

In Spain, managing directors spend an average of nine years in the job. It is surprising that 26 percent of CEOs have been in the job for less than two years. It should be highlighted that some of these brief mandates relate to CEOs in transition, that is to say, executives who are bridging the gap between a CEO who is departing and the new appointment, while the company seeks the ideal candidate.

In sectors such as consumer goods, basic materials, industry and construction or financial services and real estate, the managing director’s mandate is on average usually longer than nine years. On the other hand, in more dynamic sectors, such as technology and telecommunications, oil and energy and consumer services, CEOs usually have shorter mandates.

Finally, it’s worth noting that CEOs who have managed to stay in the job the longest, leave their positions through death, for personal reasons or illness, or through retirement.

Succession: the last great challenge of a CEO

Stepping down from a lofty post, CEOs may suddenly find themselves feeling useless, disoriented and set adrift.

Apart from these fears, retiring CEOs need to consider the image they will leave behind. A shining reputation built up over years of sterling service can be tarnished overnight by a refusal to go gracefully or through petty acts of sabotage against a successor.

What is the best way to bow out? In the same spirit in which the post was accepted: looking to do what is best for the company. There are two ways a CEO can create value at this stage, and even after leaving the post.

1. Share information with the successor. They say you never fully understand the job of CEO until you have experienced it for yourself. Imagine the value to the incoming CEO of getting wise counsel from someone who knows the job and the company inside out. Some companies have institutionalized this transfer of knowledge and experience.

Unfortunately, this does not happen everywhere. Many firms pay the outgoing CEO to be available for consultation if necessary, but they rarely get their money’s worth, either because the new CEO sees it as his job to shake things up, or he wants to prove to the world that he can manage on his own. The outgoing CEO does his company, and his legacy, a huge favor if he extends a helping hand to his successor, passing on his vital knowledge and experience. But it must be offered in good faith, with no hidden agenda.

2. Boost the successor’s authority. Ideally, once the substitution has been announced, the incumbent will let the new executive take charge. After that, it will be best if he disappears for a while. Then, employees will have no choice but to refer to the new boss.

The two executives should agree on how to present the succession to employees and other audiences. It is not in the company’s interest to issue conflicting statements or display disagreement over corporate goals. Invariably, some aspects of the new CEO’s mandate will highlight areas in need of improvement, and the outgoing executive will have to humbly accept, officially at least, that some change is needed and support the new management unreservedly. Best is to keep less generous thoughts to yourself. Do not try to do the new leader down in order to make your own tenure seem better: you will run the risk to be the loser.

Some key conclusions for practitioneers

Conclusions can also vary dramatically depending on which variables you choose to include or omit. Say you want to study the influence that a CEO has on his company’s performance. You may decide that performance depends on two things – the effort of employees and the proven qualifications of the CEO – so that, effort being equal, better CEO qualifications would yield better performance. Right? Well, maybe – until the influence of the economic environment is factored in. Then, you would probably find that company profits depend more on the general state of the economy than on the quality of its management. This is because, in the real world, there are dozens of such variables that influence company performance, and each experiment is only as revelatory as the variables allow. You only ever see the trees, not the wood.

In our opinion, many questions can only be answered if we take the human factor into account and stop trying to avoid the complexity involved in human decision-making. For once, we need to take the competency factor seriously. And we need to clarify which competencies are most important for a chief executive. Based on our research, we are inclined to believe that competencies or the lack of them, explain most failures. Among them, the ability to manage power and influence multiplied by the generation of trust seem to be essential to become and remain CEO. In fact, the lack of awareness of the CEOs make them basically their own worst enemy.

About the authors

Guido Stein is associate professor at IESE Business School in the Department of Managing People in Organizations. He is also executive president of EUNSA and EIUNSA. Prof. Stein is a consultant with firms in diverse sectors such as finance, industry, energy and professional services. He has authored numerous books including Managing People and Organizations: Peter Drucker’s Legacy.

Manuel Gallego is a research assistant at IESE Business School.

[/ms-protect-content]