By Steve New and Dana Brown

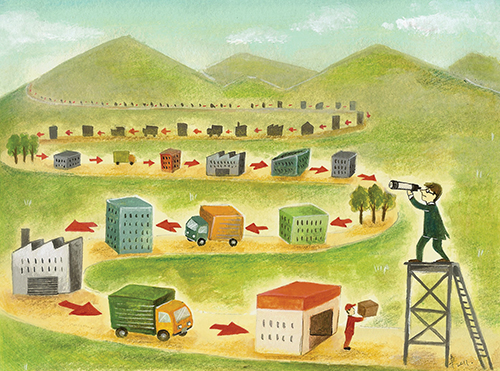

In this article we examine a key business question: how much should organizations know about their extended supply base, and what should they do with this information? This question has become of urgent practical significance for firms across industry sectors, as they square up to the complex inter-connectedness of the modern world. We present a series of challenges that firms can use to frame an initial review of their own practices.

The 11th March 2011 was a day when the earth moved. The massive earthquake that hit Japan – the fifth largest since 1900 – generated a tsunami which roared across the ocean at the speed of a jet plane; the devastation and human tragedy that followed caused the whole world to pause and gaze in horror. Soon after, media reports of the incident were dominated by the crisis caused at the Fukushima nuclear plant – a crisis which is still being played out. But the aftershocks of the disaster were not limited to Japan, as the devastation of industry in the region has had consequences for the world as whole. The disruption of global supply chains has been significant, even if less than originally feared in the first few days after the event.

Hewlett Packard predicted a loss of sales of $700m due to the earthquake. Honda’s production of Civics in Indiana and Ontario is expected to be disrupted until the autumn of 2011. UK set-top box manufacturer Pace blamed substantial drops in profits on shortages caused by the disaster; Nokia issued similar warnings. The nuclear crisis prompted by the disaster also resulted in temporary bans on food imports from Japan. Suddenly, the complex interconnections of the world economy are more than theoretical propositions, and the question “where does this stuff come from?” is a board-level concern. What is striking is that firms often find this question difficult to answer.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

But catastrophic natural disasters are not the only reason why firms have had to address the issue of product provenance in recent years. Iconic firms such as Wal-Mart and Apple confront reputational firestorms when ethical and environmental problems within the supply chain capture the attention of journalists and activists. It would be easy to shrug these worries off with the (entirely correct) observation that these firms’ customers are mostly indifferent to these concerns when it comes down to the purchasing decision, but to do so misses some important points. Firstly, firms need to guard their reputations not just with regard to their immediate customer base and short term bottom line, but because continued reputational problems often lead to slow erosion of market position. Secondly, firms are finding that reputational damage affects not only their ability to hire the best staff, but also to attract investors and to be considered a trustworthy and legitimate business partner. Finally, governments and consumers are increasingly concerned with product safety and quality, an issue that is impossible to manage without good information about the supply base.

To understand the increased urgency of these issues, it is useful to reflect on the factors that have changed the game over the last twenty years. While the global interconnectedness of economies is not unique to the modern period, there are features of this globalization that are profoundly different from the past. Above all, high bandwidth global communication technologies have radically changed the nature and timeliness of information, and who has access to it.

The volume and immediacy of information flow today means that global trade operates in a completely new way. Basic written information can be translated for free, and instantaneously; multi-party, face-to-face discussion can be organized and executed in minutes. Complex documents can be shared, and co-written, in real-time across continents.

Just as the financial crisis has shown us how the notion of the ‘local’ in financial industries is now almost invalid, events like the Japanese earthquake show us how consequentially entangled our lives have become. Not only have the business dynamics changed, but increased connections mean that I find myself in complex commercial interdependencies and ethical entanglements. Information is not only a tool for me, but for others who can hold me accountable. Just think about the activist who discovers a child worker in one of my factories and can share the discovery with my customers and the public within hours. In the old days, I could mount a plausible defence that what happened further down the supply chain was nothing really to do with me; this has become increasingly unacceptable.

It is salutary to observe that this pace of change means that anyone old enough to be leading a global company now began their career in another industrial era. Senior managers cut their teeth in a business environment which worked on rules and assumptions that no longer really apply. The new age brings a series of daunting challenges: what can firms do to face up to them?

Challenge One: Do you have supply chain visibility?

An obvious question to ask with regard to the new reality of global business is how much information firms really have about their supply chains. Our research indicates a vast range of answers to this question. Some firms have chosen to undertake meticulous analysis of their sources of supply, stretching back five or six tiers of supply or more. Others settle for no more than a passing knowledge of the first tier; in some cases, where firms make use of agents, they have almost no reliable knowledge of the details of their supply base. This wide disparity of approach is in part explained by structural features, but also reflects firms’ choices about how they handle risk.

The structural issues include the complexity of the product, the nature of the technology, and the degree of commoditization at each point in the supply network. In many cases, firms are dealing with many thousands of first-tier suppliers, and thousands of items being procured. In turn, each of these items may themselves have hundreds of components or ingredients, with concomitant numbers of suppliers. So even the issue of data handling is not straight-forward, and firms which lack systematic approaches to the problem are likely to be substantially exposed to risk. This challenge is exacerbated in those industries where the rate of technological change is high; the supply network is not just complex, but also fluid. Assumptions and rules-of-thumb that apply now may be redundant in only a few years’ time. Firms also are faced with the difficulty of handling the points in the chain in which products and items are standardized across companies (for example, products produced to international standards) and the points in which production is bespoke to the next link’s specification. Broadly, where a buying firm defines the product, the greater its ability to harvest information, to impose standards, and to affect change; this power, however, also brings a greater degree of culpability in the event of some kind of problem.

Firms facing up to this challenge need to think in terms of the separate elements of this problem: how and what data to collect; how it is verified; and, how to enable the data to be stored and handled. In some cases, the rational decision is to operate a delegated, post hoc approach where, rather than centralized holding of data, firms work on the principle that if they needed to know about provenance for a particular purpose, they could find it out, because the tiers in the chain could be followed through. This approach takes the least effort, but means it is impossible to achieve any proactive, pre-crisis risk mitigation. If instead data is sought that describes several levels down in the chain, appropriate rational rules are needed to avoid being swamped in data, or adding counter-productive cost burdens on suppliers and their suppliers. These rules also need to come to a clear view of what standards of evidence are to be demanded of suppliers (for example, if a supplier says that none of their suppliers use child labour). Finally, firms need to face up to the fact that the new supply challenges are not well handled by most existing Enterprise Resource Planning systems; holding data on suppliers beyond the first tier presents substantial information management issues which require thought and investment.

Challenge Two: How much supply chain visibility do you share?

Historically, firms have generally been circumspect about revealing detailed data on their supply chains; such data is generally perceived to be strategically important, and in some cases there are genuine risks of industrial espionage or even sabotage. Furthermore, firms have worried about the scope for reputational damage if something embarrassing in the chain comes to public attention. However, increasingly firms are figuring that the new information age means that any competitor or activist group who seriously wanted to know the identity of suppliers could easily find the information for themselves, so that there may be limited value in seeking to keep things secret. Indeed, there may be some commercial logic for pursuing a degree of openness about the supply chain, not least because it may help establish trust in the minds of consumers and investors. Moreover, there are a number of ancillary benefits. These include the fact that – in the event of some kind of supply chain failure – it may be easier to deflect reputational damage to other parts of the chain.

Additionally, some suppliers may be keen to be identified as suppliers to a given firm as a way of establishing their credentials in the broader marketplace. In some cases, the origin of goods becomes an important feature of the goods themselves (for example, in organic or cruelty-free farming), and the greater degree of disclosure may itself become a marketing benefit.

These decisions, however, are not at all straight-forward; offering greater visibility in the supply chain means in some cases that there is a heightened chance of competition arising from your suppliers establishing direct links with your customers, which may threaten your own business, or at the very least diminish bargaining power over the supplier. For these reasons, decisions about the extent to which firms make their supply chain network transparent to outsiders is a question of strategic significance, and which needs to be addressed at board level.

Challenge Three: How do you face risk when you find it?

Having addressed the previous two challenges, the next problem is what to do with the information collated. For example, the analysis may have thrown up that one or two layers down in the chain lies a firm on whom your operations are surprisingly reliant. Or it may become clear that a supplier whose own processes are unimpeachable may sometimes contract out to firms that present substantial reputational risk. In these cases, firms have a series of choices to make, ranging from restructuring the chain itself (for example, dropping a supplier) proactively and directly working with the point of vulnerability, or seeking to ensure that any consequence of failure is trapped at another point in the chain. An example of this last strategy could be to increase the brand visibility of the supplier, so that reputational damage gets them rather than you. For example, by naming the suppliers of own-label food products on packaging, retailers may be able partially to deflect blame in the event of a problem of quality or safety.

In all of these aspects, firms who can develop clear and consistent policies for applying these various approaches are likely to reap substantial rewards. We have observed that firms’ efforts in supplier audit are frequently not driven by coherent business objectives, nor targeted carefully. These firms risk a waste of resources on their efforts, as well as reputational damage. When a problem arises, firms that have taken coherent action will have the most ability to react and rebound.

Challenge Four: What do you need to organise for the new era?

Squaring up to the issue of supply chain provenance and transparency requires that firms look closely at how they fundamentally organize procurement. For example, we observe that it is not uncommon for firms to separate work on supplier environmental and ethical auditing, and supplier compliance with international standards, from the mainstream procurement process. This can lead to suppliers being faced with contradictory demands from the buying organization. For example, a compliance officer may be keen to insist that a supplier is investing appropriately in systems to monitor its own suppliers; a buyer may simultaneously be focused on driving down price. The supplier, understandably, may sense that the customer is really saying, give us the best deal, and say some things we want to hear but not make substantive changes to their practice.

Firms need to respond to the new challenges of the supply chain by realizing that procurement personnel need a much broader skill set than traditional buyers. Previous steps in the professional evolution of purchasing has meant that it has long been accepted that buyers need to be well versed in the production technologies of their suppliers, and to have a sound understanding of the markets in which they operate. The new agenda adds a further layer of competencies: buyers need to be able to map out supply chains and manage risks. They require knowledge of product, ethical and environmental standards, of rules and regulations and particularities of the contexts in which their suppliers operate. Firms need to revisit the training, management and professional identity of procurement staff.

Conclusions

These challenges point to firms progressively facing up to the need to collate, handle and deploy information that previously was considered remote from day-to-day business concerns. This is not to say that all firms will map their supply chains in the same way, and some may settle on having highly focused and narrow approaches. Certainly, there are costs involved in getting a clearer view of the organization’s supply base; firms will differ in the way they trade off depth versus breadth. But the new age will be harsh on those organisations that do not develop coherent strategies to address these questions.

About the authors

Dr. Steve New teaches at the Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, where he is also a Fellow of Hertford College. Originally a physicist, he entered academia after working in the aerospace, automotive and consulting sectors. His research work focuses on supply chain management and process improvement.

Dr. Dana Brownis a professor in strategy at EMLYON Business School in France, and an associate researcher at Said Business School, Oxford University. She holds degrees in Political Science and Slavic Languages, and specializes in corporate responsibility and political risk strategies.

[/ms-protect-content]