By Sylvain Guyoton and Hervé Legenvre

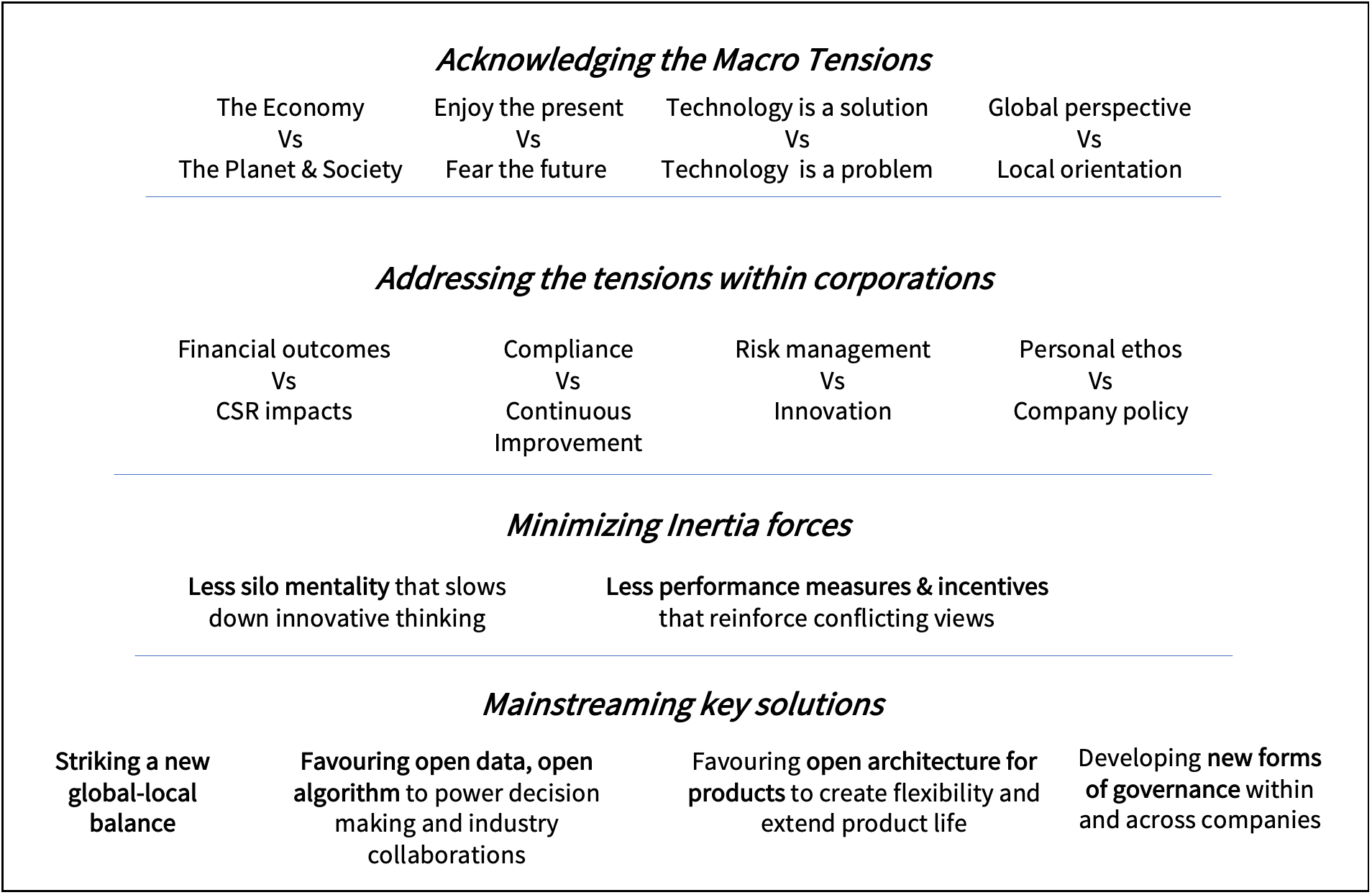

The following discussion took place In April 2020. We aimed at confronting our points of views on the contradictory forces that needs to be handled to address the sustainability challenges ahead of us. The key ideas are summarised on figure 1.

Hervé Legenvre (HL) – The equation is becoming clearer every day. The planet can no longer sustain the present rate of economic and demographic growth without significant damage. Our ability to enjoy a safe and prosperous life is being eroded by constraints in resources and environmental conditions. Our world today is interconnected and uncertain, so even if we put all of our efforts and attention into addressing a single challenge, unintended and unexpected consequences can create other challenges and issues. An unknown virus pops up in a wet market in the centre of China and quickly spreads around the planet. Unless we re-invent how we operate both in business and as a society, the limits we are experiencing will constrain and de-scale our economic activities. Whether we call this prevention or adaptation, change is needed. We are facing a tremendous challenge with a multitude of contradictory forces. Social and environmental aspirations offer contradictory imperatives. Personal, corporate, and political agenda conflict. Tensions are growing across geographies and generations. These contradictory forces are also very visible within industries, supply chains and organisations.

Sylvain Guyoton (SG) – Even if the diagnosis is clear and daunting, we need to stress that we may actually have reached a positive inflexion point. In August 2019, 180 of the top US CEOs who are members of the Business Roundtable declared that shareholders interest cannot be the sole purpose of a corporation. They agreed that investing in people, protecting the environment, and being fair with suppliers necessitates commitment. Furthermore, the Financial Times recently asked the question, “Does capitalism need saving from itself?” And the Dean of INSEAD, Ilian Mihov, stated that “it’s time to rethink capitalism” otherwise we will be facing enormous challenges. According to John Elkington’s new book, Green Swans, a profound market shift may be emerging. Even though we are still very much at the stage where principles are proclaimed and there are lots of unknowns, in a few years we may look back at today and say that this was the year something started to move in the right direction.

HL: Unfortunately, there are numerous examples of economic actors still operating the old way, and this may not leave enough room for new ways of thinking to scale up, not to mention that environmental degradation and increasing social inequalities may lead to populism and severe social conflicts.

SG: Yes. However, when a system is in transition it carries the old way of thinking while the new way is still being implemented. I agree that this creates massive tensions. I see four types of macro tensions at play here. First, you have the tensions between financial, environmental, and social concerns. This one especially is experienced by both corporate and governments. The second one relates to everyone’s experience. All of us, as individuals, aspire to enjoy the present days, but we fear the future. We hope something will change but we feel paralyzed. Third, technology is seen as both a solution and a problem. Some people accuse technology of being the cause of our troubles while other believe the next wave of technologies will solve many of our problems. Finally, while corporations have focused for years on creating higher added value, they have created complex global value chains. Consequently, they have externalized risks, which sometimes fire back. Now they want to take back ownership of these risks and as a result, a tension between local and global has emerged.

HL: We are witnessing similar tensions within corporations. Let me describe four of them. First, any decision ends up being an arbitrage between financial outcome versus environmental and social impact. It is very difficult for decision-makers to break through this logic. Money always comes first; other concerns are adjusted against the financial gold standard. Second, most decision-makers pay full attention to compliance matters while only a few are pushing for a social and environmental performance improvement agenda. They feel accountable for a compliance breach, so the logic of protection dominates, and the logic of progression comes second. Third, I keep seeing competing forces between risk and innovation within companies. However, innovation and risk go hand in hand. Implementing concepts such as the circular economy can require a significant entrepreneurial mindset, yet large corporations remain fundamentally conservative. Finally, on a human level, personal ethos and company policies and actions can clash. This can create embarrassment, demotivation, misunderstanding and even implementation failures.

SG: We need to keep in mind how the social and environmental agenda has unfolded over time. Looking back at the 80’s, concerns about social and environmental considerations were very limited. This was not on the corporate radar screen except in very specific industries. Then, with globalisation, concerns started to rise and became public; we moved into the era of corporate social responsibility (CSR). However, decisions were still driven primarily by financial parameters. This was not the corporation’s top priority. It was the era of greenwashing. Then CSR became more serious and it aimed primarily at managing risks and mitigating negative impacts on stakeholders. Today, we need to move towards a regenerative economy that creates a fair and inclusive society while restoring and protecting natural ecosystems. We need a CSR that brings positive impact to BOTH corporations and society as a whole. We need to move towards a BOTH/ AND logic rather than an EITHER/OR logic.

HL: Adopting a BOTH/AND logic is demanding. After so many years of focusing on short-term financial parameters, re-inventing the decision-making process is challenging. And let’s not forget all the forces of inertia. For instance, we have within companies an internal division of labour, finance, engineering, purchasing, quality, and corporate social responsibility teams; all with conflicting goals. They tend to operate within a context of a hidden but sometimes harsh power dynamic that prevents common goals from emerging. Also, we see how performance measurements and incentive systems make it even more difficult to adopt demanding and contradictory common goals. Tricking the target system is a corporate sport. Some people are very skilled at it and are happy to live with this. Doing something that does not fully contribute to your own objectives is often seen as an extremely brave behaviour in companies. A lot of things need to change to implement a BOTH/AND logic.

SG: Yes, and you have the current multiplication of transformation initiatives across companies. Mandates to improve or change are coming from every direction. People are getting lost. They don’t see the bigger picture. Creative chaos and agile ways of working were supposed to make companies more efficient, but I am not that convinced today. When people come to me with new ideas, I tell them “yes of course you should try it!”. But trying one idea after another is insufficient. We need a sense of direction. The act of making a decision needs to be powered by a creative, holistic and long-term thinking approach, in other words a purpose. This is the pre-requisite to move into a BOTH/AND decision-making logic.

HL: I see your point, but implementing an BOTH/AND economy is a grand vision that requires very practical approaches. First, every decision needs to be backed up by all the data that is necessary to understand financial, environmental and social impacts. This is essential and a lot of progress can be made on this. Then, there are three ways to move from an EITHER/OR logic to a BOTH/AND one. Let’s consider contradictory forces A & B. The first way to handle these contradictory forces is to break down priorities over time. First you do A and then you do B. But this creates a risk here that environmental and social aspects will come in second far too often. The second way to handle conflicting forces is to separate the activities. We do A on one side and B on the other side. We invest in a very sustainable activity while we keep running the old-world activities. In both cases, what matters is to make sure that an overall positive trajectory is taking shape. Then the third option is to recognize the tension and seek a BOTH A and B. This requires creative and collective thinking that breaks through existing perspectives. We need both cost reduction and a better social and environmental performance. This requires us to frame problems as paradoxical directives and to broaden the search for solutions. To do this, people from different functions need to take time to understand each other’s concerns and aspirations. But they also need to explore multiple options simultaneously before making a final decision. Doing a bit more of B on top of A is not enough.

SG: But when you talk about a “positive trajectory”, you realize that such a decision-making process needs to be supported by a vision that defines the direction of the trajectory. In an AND economy we need to communicate the need to achieve BOTH A & B continuously. This vision also needs to reconcile the short- and long-term perspectives. One of the best ways to do this is to bring the stakeholders into the decision-making hub so that they can input into the company ambitions and feedback on progress. When necessary, we should recognize that it is difficult to create both A & B but also explain why we need to reconcile the conflicting perspectives. In my organisation, we try to do this by defining four pillars: customers, employees, society and the planet, and shareholders. We map the impact of our main project onto these pillars. They sometimes appear contradictory, but in the end, it’s very easy to see that these pillars can also complement each other because they are unified by a positive “raison d’être”, a kind of rallying cry that will last in the long-term. In other words, what brings them together is stronger than the contradictory forces that may be playing out in some circumstances.

HL: For me, recognizing tension is more important than claiming a purpose. In Europe, in the 80’s, companies decided they needed both economic efficiencies and quality. A lot of progress was achieved at the time thanks to a problem-solving discipline and a focus on a few projects that reconciled these grand contradictory goals. In our context, I also see three macro-solutions that go beyond a single firm perspective. The first one is to always consider what it would take to localise and operate closed-loop activities. There are lots of long-term benefits from this change. The global approach can still be relevant for some activities. However, focusing first on localisation and closed-loop will force us to think differently. Second, we need more open data and open algorithms that aid decision-making. This needs to be built by region and by industry. Openly sharing information and letting anyone at all extract wisdom from it is very powerful. Third, we need more open architecture for products and services. This prevents lock-in situations and creates flexibility. It is a necessary condition for implementing circular economies and to regaining some degree of freedom in our thinking. Proprietary interfaces limit our possibilities.

SG: From the local-global perspective, I believe that although economies need to rebalance in favor of shorter supply loops, it would be mistake to go 100% local. There are still lots of opportunities provided by global interactions. We can also leverage local experiments and replicate them. Take for example the Eden Project of Sir Tim Smit in England, a project aimed at showcasing and experimenting with sustainable environmental practices that is being replicated in other parts of the world. Local and global will remain two sides of the same coin whose tensions we must learn to better manage. Take for example the open data logic which is essential to finding tomorrow’s solutions; it’s a global logic not a local one. Global interaction will still be needed to foster collaboration. For instance, Scope 3 carbon emissions, which represent the majority of greenhouse gases emissions, will only be tackled through global industry collaboration. Finally, we also need new forms of governance, able to better associate external stakeholders with decision-making. And last but the least, if we want to transform the economy and make it a BOTH/AND economy powered by a BOTH/AND decision-making process, we also need to transform capitalism’s master discipline of Economics as advocated by John Elkington.

Sylvain Guyoton is Senior Vice-President of Research at EcoVadis since its founding in 2007. He brings 20 years of experience in Sustainability and CSR. At EcoVadis, he oversees rating operations and methodology development, and sits on the Executive Committee. Sylvain holds an M.S. in Industrial Management from Cranfield University and an MBA from INSEAD.

Sylvain Guyoton is Senior Vice-President of Research at EcoVadis since its founding in 2007. He brings 20 years of experience in Sustainability and CSR. At EcoVadis, he oversees rating operations and methodology development, and sits on the Executive Committee. Sylvain holds an M.S. in Industrial Management from Cranfield University and an MBA from INSEAD.

Hervé Legenvre is Professor and Research Director at EIPM, an Education and Training Institute for Purchasing and Supply Management. He manages educational programmes for global clients, conducts researches and teaches on innovation and purchasing transformation, Hervé holds a PhD from Université Paris Sud.

Hervé Legenvre is Professor and Research Director at EIPM, an Education and Training Institute for Purchasing and Supply Management. He manages educational programmes for global clients, conducts researches and teaches on innovation and purchasing transformation, Hervé holds a PhD from Université Paris Sud.