By Simon L. Dolan and Sara Martinez Espejo

- Why are elite athletes more susceptible to stress?

- Can sports athletes be prepared to better cope with stress? can meltdown be prevented?

- How do elite athletes cope with performance anxiety?

- What are the symptoms of chronic stress in athletes?

- Are there diagnostic tools readily available to identify chronic accumulated stress?

- Can we develop resilience in top performance athletes?

Only when athletes are able to focus their thinking and control their emotions can they maximize their abilities to successfully master their sport.

There are two events that have caught the public attention these days. First is the very sad exposure of the breakdown of Simone Biles, a top athlete that in retrospect we are starting to understand that she was subject to prolonged stress, that was undiagnosed (or ignored) and eventually lead to a breakdown; the early signs and symptoms of chronic stress were not clear to her, to her technical coaches and even to friends and family members surrounding her. What a pity. This story is heart breaking but hardly unique. More elite athletes are reporting mental health ailments such as anxiety, depression, psychiatric conditions and eating disorders. The exact percentage of Olympic athletes with mental health concerns isn’t clear, since it hasn’t been recorded.

One thing is certain: should these people be offered a valid diagnosis which detects their chronic stress and risk factors on time, the entire sad episode(s) could have been prevented. Help could have been offered to this elite athlete on time and perhaps the agony of breakdown be avoided. We estimate that similar pressures exist for other top performers throughout the world in the fields of art and entertainment, but the focus of this article is on the elite sports celebrities.

Call it serendipity, or coincidence, at the same time that the case of Simone Biles hit the headlines across the globe, a less mediatic event took place during the past several years: the culmination of years of stress research led to the development and release of a unique tool to detect chronic stress and is called: The STRESS MAP. The latter is based on over 40 years of research intending to develop a valid framework to diagnose chronic stress. Mind you, there are numerous tools available to diagnose acute stress, but this is not the case for chronic stress hence most of the signs and symptoms are hidden; they have no color and no odor as many observers say. Nonetheless, once the signs and symptoms are observable, it might be too late to intervene and prevent the negative consequences from occurring. The stress map is all about that [i]; it is a tool that is easy to use by anyone. It is based on principles of gamification, and it is perhaps the only available tool that deals with society rising killer ”Chronic Stress”.

“During the two decades (1990s/2000s) that I spent competing as an athlete on the world stage, I figured out lots of different ways to cope with game-day stress and performance anxiety on the fly, through trial and error. When it came to mastering my mental game and breaking a Guinness World Record, there wasn’t a “method to my madness.” I didn’t have a sports psychologist with a Ph.D. on hand to give me the inside scoop on tried-and-true ways to optimize one’s mental game” – (Christopher Bergland, Psychology today” – https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-athletes-way/202006/3-universal-ways-elite-athletes-cope.

The objective of this short paper is to further expose the chronic stress of top sport performers and offer to professionals surrounding them the use of contemporary and recent tools that can be used by anyone to help them realize their particular situation and perhaps provide the help and resources to help them maintain the high performance while avoiding meltdowns. Along this line, two recent studies by Leis et al (2020) and (Poulus et al., 2020)[ii] who have investigated stress and coping in esports, bring to bear the influence of mental toughness – or resilience- among world-class sports athletes (who play video games competitively in multiplayer online battle arenas) compared to traditional athletes who interact face-to-face in the flesh. These findings were published on April 28 in the Journal Frontiers in Psychology, and showed that in order to cope with stress, Olympic top-level athletes need absolutely to engage in 3 simultaneous activities:

- Emotion-Focused Coping (EFC): Using emotion regulation and other mindfulness techniques to calm “fight or flight” stress responses.

- Problem-Focused Coping (PFC): Actively troubleshooting and problem-solving to counteract stressful stimuli in a specific context.

- Avoidance Coping (AC): Using avoidant strategies to disengage physically or psychologically block out a source of stress.

Furthermore, the latest studies in neuroscience and psychology show that 80% of the athlete’s performance is mental, which implies that if we do not prepare and train our mind, we can never achieve our 100%. The brain is just one more muscle and as such must be trained; the brain directs the show. You train as you perceive, as you think, how you act and ultimately how you feel.

However, in order to do all that, the first step for the athlete (or his/her coaches) is to develop this level of consciousness. Thus, a valid and reliable diagnostic tool is really needed. Wellness coaches and other mental health professionals are aware of the importance of training elite athletes, ever since the breakthrough message contained in the bestselling book of one of the co-founders of the coaching profession, Timothy Gallway (1972) who wrote: “The inner Game of Tennis”[iii]. The message of the inner game is simple: “focus on the present moment, the only one you can really live in”. In his book, Gallway asserts that “Freedom from stress does not necessarily involve giving up anything, but rather being able to let go of anything, when necessary, and knowing that one will still be all right”. And finally, in this classical book, it is suggested that almost every human activity involves both the outer and inner games. There are always external obstacles between us and our external goals, whether we are seeking wealth, education, reputation, friendship, peace on earth or simply something to eat for dinner. In the end our obstacles are always there; the very mind we use in obtaining our external goals is easily distracted by its tendency to worry, regret, or generally model the situation, thereby causing difficulties from within. Freedom from stress happens in proportion to our responsiveness to our true selves, allowing every moment possible to be an opportunity for self to be what it is and enjoy the process. As far as we can see, this is a lifelong learning process. The true question is how do we get to this point? How do we develop to reach this state? What is the extent that coaches and those surrounding us can help us get there? And most importantly, what tool (s) are available to help us diagnose the outer and inner noises that generate stress and prevent us from focusing on the here and now (and nothing else)?

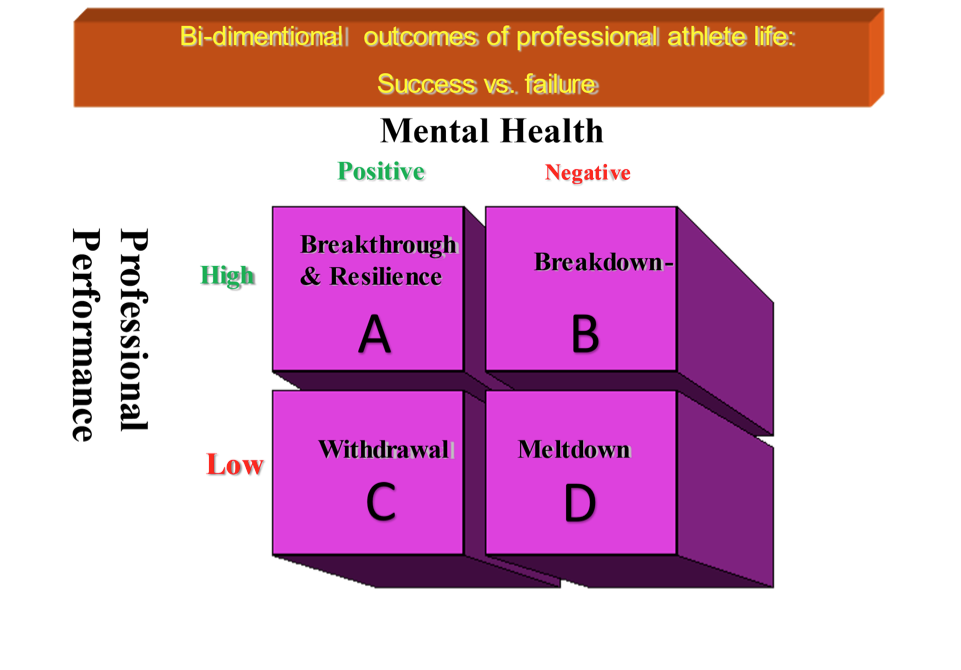

And here is where the recently developed STRESS-MAP can become an important diagnosis ally of athletes and their coaches. This tool was based on a long journey that begun at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota while Simon L. Dolan (co-author of this paper) completed his doctoral studies at the Carlson Graduate School of Management. In the clinic, he observed many patients who survived their first heart attack for which started a mental journey questioning the essence of life (following this health crisis); is it really worthwhile to commit totally to work? What about the physical and mental consequences of this total dedication? Actually, the entire issue of what constitutes professional success came to bear. The conclusion of this reflection was obvious: being excellent in what you do professionally but suffering premature physical or mental health consequences, does not constitute a real professional success. Issues like that, led to two subsequent observations and conclusions:

- We are witnessing a new form of toxicity. It has no color and no odor, and have no obvious early signs or symptoms, but can lead to premature physical and mental ailments and even to death; this is what chronic stress is all about.

- We need to revise our definition of professional success to include at least two dimensions: A professional performance dimension, but also a personal health dimension.

While the idea is generic and can apply to many professions, in Figure 1 we propose the case of the elite athlete.

Figure 1:

Quadrant A: Breakthrough and resilience – This is an ideal case. This is the quadrant that most athletes opt for. It means that the athlete is able to reach record performance and feels mentally positively and complete. Some people refer to this state as a state of flow. It is that sense of fluidity between the athlete body and mind, where he/she is totally absorbed by and deeply focused on the professional task or challenges, beyond the point of distraction. The state of flow was popularized by positive psychologists Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Jeanne Nakamura when the person becomes fully immersed in whatever he/she were doing. Csikszentmihalyi and Nakamura reached this conclusion by interviewing a variety of self-actualized, high-performing people including mountain climbers, chess players, surgeons, and ballet dancers[iv]. Mind you, the flow mental state is generally less common during periods of relaxation and makes itself present during challenging and engaging activities. But if is it happening during multiple moments of competition it can be inferred as a state of true resilience.

Quadrant B: Breakdown – Breakdown happens when the athlete realize that he/she pays the mental prize of sustaining high performance continuously. There are many studies that show that high performing individuals that lack the resources to overcome the continuous demands on them, end up overwhelmed and they break down. The breakdown can be manifested in several forms but the most common is burnout and depression. Depression is not about having an off day. It is more substantial and negatively affects how the athletes feel, think, and act, and eventually diminishing their ability to function well professionally but also at home. And there is also the case of minor mental breakdowns; when athletes over-think sport situations to the point where fear and anxiety disrupts the natural execution of sports skills – the problem is a mental breakdown. For example, when you see an athlete become upset after a bad play and loses focus in the plays that immediately follow, the athlete is suffering from poor emotional coping skills – or a mental breakdown.

Quadrant C: Withdrawal – This is the quadrant very typical to many athletes. We all know that top performance in many sports is determined by the length of time spent playing the sport, the competitive level achieved, and the amount of time spent in training and competition. Obviously, there are distinct types of sports, some that do not necessarily have an age expiry (i.e., Golf). But this is the exception. More elite high-performance athletes are aware of their expiry capacity and prefer to withdraw from a single competition (or from the sector altogether) before it affects their mental state. And there is also a partial withdraw that avoids excessive stress. For example, Japanese tennis player and the world number 1, Naomi Osaka, withdrew from a post-match press conference citing high stress, which also invited her to a huge fine and ire, but solidarity from fellow athletes has been coming which shows empathy to her condition. And again, this was the case of Simon Biles, a celebrated athlete and medal-winning, high-profile gymnast who has decided to withdraw even before the competition as she perceived a low performance result. Withdraw happened even before the act

Quadrant D: Meltdown – this is the worst-case scenario hence you really lose it all. Obviously in the long term may require professional health assistant in order to climb back to normal life. In a meltdown situation, the athlete throws the towel and decided to not going back to the competition anymore. But there are also episodes of partial meltdown, that become chronic if they are repeated. And again, because we are living these days through the Olympic experience, let’s quote a phrase from the media:

“Saturday, after already losing two straight matches — semifinals in singles and mixed doubles — Djokovic completely melted down in the bronze medal match. He threw his racquet into the stands; he would have been ejected, or even arrested for that under different circumstances, but no spectators in Tokyo worked to his advantage. Later he smashed his racquet into the net pole during a changeover and threw the mangled piece of equipment into the photographers’ pit.”

Greater lifetime stress made athletes more susceptible to future stressors. Research suggests that elite athletes are at increased risk of poor mental health, partly due to the intense demands associated with top-level sport. Despite growing interest in the topic, the factors that influence the mental health and well-being of elite athletes remain unclear. From a theoretical perspective, the accumulation of stress and adversity experienced over the life course may be an important factor (McLoughlin et al, 2021)[v].

Elite athletes are expected to perform at the top level over an extended period of time and are expected to deliver extraordinary results continuously. Actually, they are expected to be superman (or superwoman) for a prolonged period. And research shows that if you do not have proper mental preparedness, this is impossible. Prolonged pressures in many other professions end in burnout, depression, and other psychological ailments. The pressure that mounts on elite athletes comes from family, friends, coaches, and the public. All of the elite athletes’ stakeholders are often guilty of placing unrealistic expectations on them. This may result in feelings of insecurity and displeasure in their achieved progress in their sport, comparing themselves to their chronological peers. As a consequence, some who are not psychologically prepared may lose self-esteem and withdraw from the sport or from particular events in which they perceive their competencies to be challenged. In our opinion, this was the case of Simone Biles during the ongoing Olympic games or the case of Rafael Nadal who has decided to withdraw in 2021 from top competitions such as Wimbledon or New York open tennis. Obviously, having injuries or other circumstances of improper fit can be used as a pretext for the withdraw hence admitting mental misfit is not considered proper. Nonetheless, we all know that coping with stress in sport is a pivotal self-regulatory factor that promotes optimal levels of sporting achievement. Individual-related factors (personality, motivation, cognitive evaluation) are key predictors of sport-related coping. Task-oriented coping represents the strategy to directly manage the stressful situation (that is, problem-focused) and its resulting cognitive and affective activation (approach emotion-focused). This is also called approach or engagement coping and includes strategies such as effort expenditure, thought control, relaxation, logical analysis, mental imagery, and support seeking. All these are the essence of the 4 pillars model of chronic stress that is embedded in the Stress Map tool.

The Stress Map Tool

The idea of developing the stress map followed a long journey into research on understanding chronic stress. Admittedly, the research did not focus exclusively on stress in professional sport, but the generic model and principles can apply perfectly to this sector. The research team under the helm of Simon Dolan (co-author of this paper) has published over the years a dozen articles in scientific journals based on empirical results of their studies in different sectors, countries and occupations; they also wrote several bestselling books (in multiple languages) such as “Stress, Self-Esteem, Work and Health (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2006), and an updated edition of the book in similar format is forthcoming in 2022 and is entitled: DE- Stress at Work: Understanding and Combatting Chronic Stress (Routledge).

The 4 pillars that can help diagnose chronic stress and vulnerability include:

- Identify the density of the signs and symptoms of stress in the past 3,6, or 12 months (the latter are identified at the psychological, somatic, physical, and physiological levels); density is a new algorithm developed for the stress map that multiplies the severity of the sign/symptom by the frequency of occurrence. This can generate a type of hierarchy of the signs and symptoms of poor coping of the athlete.

- Identify the core possible sources of stress (in the work and non-work setting). Research indicates that both spheres of life are important due to a spillover effect, where sources of stress in one sphere of life of the athlete affects the other.

- Identify, what we label the “meta sources of stress”. This addresses the following questions: does the elite athlete live in congruence with his/her core values? does the elite athlete has a conflict between dedication to his sports passion and simultaneously commitment to family demands? And does the elite athlete have TRUST in the coach and the technical team that prepares him/her to sustain top performance?

- Identify the modulators that can either exacerbate or filter the negative consequences of stress. Here comes to bear some personality traits of the athlete and other individual characteristics known to modulate the stress syndrome; it includes personality proneness to stress, lack of support systems that are available and the perception of lack of control or resources to perform well.

In order to help the elite athlete to cope with this pressure and prevent crackdown, a mix of two critical elements is needed: 1) a good coaching process (psychologically as well as technically), and 2) a good diagnostic tool that will help the coach build and prepare the athlete for enduring resilience.

Effective coaching requires not only the establishment of a satisfactory relationship but also adequate physical, technical, mental, and tactical preparation of the athletes. Supportive coaching is used to refer to a broad and multi-faceted coaching style that incorporates distinct yet interrelated emotional/relational and structural/instrumental components of effective coaching. Supportive coaching can play a positive role in providing guidance in the goal-striving process and nurturing athletic and mental skills. It can be seen as a resource likely to make athletes more capable of problem-solving and preparing them to cope with the stress inherent to sports competitions. Task-involving motivational climates is positively correlated with task-oriented coping. By contrast, an environment that includes an ego-motivated coaching culture may provide athletes with an unsupportive coaching style. As a result of an unsupportive environment, athletes experience excessive pressure from coaches, favoritism, and greater time spent with the best athletes are important risk factors for impaired self-regulation. This is shown by associations between ego-involving motivation climate and the use of disengagement-oriented coping in the sports domain (Nicolas, Gaudreau et al. 2011).[vi]

There is ample research suggesting that holistically young aspiring top athletes are at risk of developing burnout, as they face not only high physical demands but also psychological pressure to reach the elite level. Burnout appears to be linked to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors in a person’s relationship with their work. In athletes, burnout is associated with negative outcomes such as performance impairment, reduced enjoyment, depressed mood and, potentially sport termination. Optimists perceive their life as less stressful than pessimists, which may be why they are less likely to burnout Exhaustion is a central component of burnout and is related to stress associated with intense training and competition demands. A reduced sense of athletic accomplishment is manifested in the perception of low ability with regard to performance and skill level. Sport devaluation manifests itself in a loss of motivation, with the athlete ceasing to care about his or her previously beloved sport.

So, the role of a psychological coach is essential in preventing stress and burnout in athletes. An effective, proactive, and preventive approach to stress management adopted by the coach seeks to make changes in the macro-environment (organization culture), the microenvironment (task redesign), or in the athlete perceptions of control (for example, enhanced decision-making opportunities). Organizations and official delegation management teams are recommended to proactively address the underlying causes of the stressors, establish effective mechanisms to recognize and respond to stressor warning signs and implement systematic learning, un-learning and re-learning in order to get rid of habits and behaviors that can eventually become counterproductive. The stress map tool can aid the coach in pinpointing and diagnosing the Achilles points and develop effective preventive strategies. Further interventions should focus on moderating external pressures for the athlete and monitoring and modifying their training demands.

We realize that the stress map is not a panacea. Yet, it is an important tool that has been backed by years of scientific research and is at the disposable of all coaches. We really hope that episodes such as we have witnessed these days with the case of Simone Biles will not hit the headlines and most important reduce the suffering and agony of the top athletes, their families, and their fans.

Simone has won in these Olympic Games, and more importantly has made many athletes win, giving visibility and normality to psychological injuries just as it is done with physical injuries. If an athlete ruptures a ligament, he/she cannot continue competing; if an athlete has a severe episode of anxiety crisis (stress), he/she cannot continue competing. Where is the difference? Why don’t we treat it the same in our advanced intellectual society? At the end, we are trying to create a better society. Isn´t it the spirit of the Olympic games?

Unlike machines, humans do not simply follow algorithms that lead to perfect solutions. Coaches generally do a good job of teaching sport skills, but when athletes are called to execute the skills in which they have learned in competitive situations, they often fall under pressure – and end up choking as a result. Making things worse, most athletes go back to only practising the physical elements of a sport skill, and often disregard the importance of being able to control nerves and emotions (mental skills) the next time they feel pressure in a competitive situation.

The mind of the athlete is their most valuable tool and their most impactful asset in and out of the sport. And it is also the most susceptible to external influence. Athletes are more than their results. Michael Jordan always said that he was blessed to have a High-Performance Coach – Tim Grover. ”I consider my mental coach to be an essential part of my training program.” So, we make a call to coaches, family and friends of the athlete to engage collectively and support resilience and high performance of the athlete but apply judgements and use the latest psychological tools and resources to improve the mental assessment and bring the situation to endure resilience. And, if along the athlete journey, some psychological dumps surface, that’s not the end of the journey hence early detection can lead to intervention and prevention.

About the Authors

Simon L. Dolan is the president of the Global Future of Work Foundation and Honorary president of ZINQUO. He is a prolific writer and researcher, with over 77 books published (in multiple languages), over 150 articles in scientific journals, and over 600 conferences delivered throughout the world. He has been a professor at some of the leading business schools (ESADE, McGill, Boston – to name a few). He is a very solicited international speaker hence he speaks 7 languages. For more information visit his website: www.simondolan.com. Email: simon@globalfutureofwork.com

Sara Martinez Espejo is an experienced People Director and Executive Coach, with more than 10 years in Human Resources roles working in an international environment across Europe, Japan and LATAM in Multinational companies as well as Startups. She is a psychologist, certified coach trained at the Tavistock Institute in London, certified high performance coach trained at Elite High Performance Coach in Canada, and the Managing, Leading and Coaching by Values certification from ZINQUO (Barcelona). For more information visit his web site: www.elite-coaching.es. Email: hola@elite-coaching.es

References

- [i] To learn more about the stress map: https://vimeo.com/517221671 . And even more details available in Spanish: http://simondolan.com/the-stress-map-our-latest-diagnostic-tool

- [ii] Oliver Leis, Franzisiska Lautenbach, Phil Birch and Anne-Marie Elbe (2020) Stress and coping in esports, Conference: 52. Jahrestagung der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für SportpsychologieAt: Salzburg (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341575312_Stress_and_coping_in_esports); Dylen Pouloud, Tristan J. Coulter, Michael G. Trotter and Remco Polman (2020) Stress and Coping in Esports and the Influence of Mental Toughness, Front. Psychol., 23 April (Frontiers | Stress and Coping in Esports and the Influence of Mental Toughness | Psychology (frontiersin.org)

- [iii] Tim Gallway (1972) The inner Game of Tennis. https://theinnergame.com/

- [iv] For an interesting interview on the secrets of Flow, see this TED video: https://www.ted.com/talks/mihaly_csikszentmihalyi_flow_the_secret_to_happiness

- [v] Ella McLoughlin, David Fletcher, George M. Slavich, Rachel Arnold ,Lee J.Moore , (2021) Cumulative lifetime stress exposure, depression, anxiety, and well-being in elite athletes: A mixed-method study, Psychology of Sport and Exercise, Volume 52, January

- [vi] Nicolas, M., P. Gaudreau and V. Franche (2011). “Perception of coaching behaviors, coping, and achievement in a sport competition.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 33(3): 460-468.

Disclaimer: This article contains sponsored marketing content. It is intended for promotional purposes and should not be considered as an endorsement or recommendation by our website. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and exercise their own judgment before making any decisions based on the information provided in this article.