Boards can prove easy targets for their critics. Below, Andrew Kakabadse discusses how to make boards work, and argues that directors should be independent enough to raise questions and challenge management decisions, while board diversity must be linked to the company and corporate structure.

Company boards are increasingly coming under public scrutiny as their decision-making and leadership processes are examined and often called into question in an era which is demanding higher levels of transparency.

Boards can prove easy targets for their critics. They can be attacked for the levels of power they wield, for falling down on the job, and even for their real (or perceived) interference in entire economies, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

At the same time the expectations on non-executive directors are being stretched further than ever before, often to the extent that their impact offers little more than status-value to the businesses they are supposed to serve and support.

Many non-execs hold anywhere between four to 30 such positions, a numbers game which makes it impossible for them to fully understand what is happening at the heart of an organisation. Board members simply don’t have the time to deal with the responsibilities of the job and so avoid challenging their counterparts on core issues affecting a business.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]All of this means that chairs and non-execs alike are becoming – quite rightly – concerned about their professional and legal liabilities, as well as their moral responsibilities. Their risk-taking capacities are minimised by the likelihood of them making serious mistakes, which could result in the redundancies of thousands of people and even the failure of an entire organisation. This is pushing boards towards supporting chief executives without necessarily addressing or acting upon the information placed in front of them.

The number one questions for both aspiring and existing board members is ‘do they really understand their organisation’s competitive advantage and how it should be positioned?

Additionally, careful consideration should be given to how board members interpret and deliver governance which enables a business to perform more effectively, while maintaining grounded ethical and moral positions in the marketplace.

For example, is corruption the norm in different operating markets? If ‘yes,’ how should the organisation respond? Does it move out of those markets, and will shareholder value be damaged if it does so?

Global industry is indeed under increasing pressure from both bribery and illicit behaviour across industries including the food, pharmaceutical and natural resources sectors. Non-execs are overlooking serious misuses of governance because they fear the consequences of attempting to confront unwelcome practices in foreign governance regimes and cultures.

The key mentoring influences that should be on offer from a boardroom – support, stewardship and leadership – are becoming wildly negligent in this respect, particularly in the UK and the United States. A consequence of this lack of accountability means that it is managers, rather than board directors, who go to jail when things go wrong.

So what can be done to address these seemingly insurmountable challenges, and how should boards go forward to achieve their organisational purpose?

Business Schools and the Realities of World Trade

An important starting point needs to be in our Business Schools, which must prepare the next generation of executives for the realities of world trade. Graduates need to be fully equipped with an understanding of boardroom behaviours and the values offered by an ethical operating culture.The selection criteria for non-execs is unclear and boards are suffering from a debilitating clubbiness which must change.

More than anything else non-execs need to be clear about their own purpose. If they are to genuinely add value to an organisation they must understand and respect that engaging management teams and workforces is paramount, and this can only be achieved through an ongoing and honest dialogue with stakeholders.

Another key issue for boards is remuneration. How do you pay executives fairly, but in a way which protects your organisation’s reputation?

In the book ‘How to Make Boards Work – An International Overview’ – I, and my fellow contributors, address the impacts of boards and the critical leadership functions of the Chairman, which include:

• Setting the ethical tone for the board and the company

• Identifying and participating in selecting board members and overseeing a succession plan for the board

• Formulating the yearly work plan for the board, CEO and certain senior management appointments

• Managing conflicts of interest

• Ensuring that directors play a full and constructive role in the affairs of the company

• Monitoring how the board works together

• Ensuring good relations are maintained with the company’s major shareholders and strategic stakeholders

This list is not exhaustive but becomes particularly pertinent when held up against our research with leading FTSE companies, which identifies many boards as being significantly disengaged from their companies and struggling to respond to the rapid market changes being driven by globalisation. A significant barrier to success is that over 80 per cent of board members simply don’t know what the competitive advantage of their firm is.

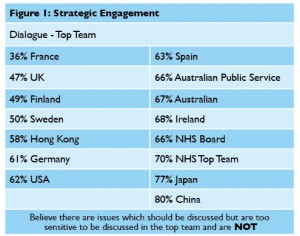

Among top management, 33 per cent lack a shared vision, mission and strategy, and many add they know what is wrong with their companies, but are too inhibited to talk openly with boards about problems and solutions (Figure 1).

A lack of understanding and honest dialogue leads management to become overly defensive with their boards, either not giving them important information, or providing inappropriate or inadequate details in the hope of keeping them placated. This low level of engagement is damaging companies.

The extent to which board diversity is pursued should be based on business need. Successful companies tend to focus on three key elements: enterprise value, diversity of thinking, and a culture which promotes both mission and engagement.

Directors should be independent enough to raise questions and challenge management decisions, while board diversity must be linked to the company and corporate structure.

For example, EasyJet’s Board has a person who knows something about airlines, working alongside colleagues with knowledge of areas including media and northern Europe. These individuals offer a collective insight into what gives EasyJet a competitive advantage in its markets. Board members also need to be interventionists, without crossing the line into interfering – a balancing act that can be hard to achieve.

Multinational corporations are operating across so many different markets that management teams must start becoming more versatile in how they respond.

On 1 September, 2013, the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing’s Code Provision was introduced to encourage greater diversity in boards among the country’s listed companies, a development which followed the Exchange’s 2012 requirement for one-third of board members to be independent non-executive directors.

This, and similar emerging initiatives, are being initiated to address an all-too-apparent lack of diversity and engagement in the boardroom, while also encouraging more varied thinking to change the way in which boards operate and interact with company management.

Scenarios identified as being important to avoid include engaging directors who sit on too many boards, diluting their effectiveness, or directors who are too personally close to the chairperson. The latter leads to individuals feeling unable to voice dissent or propose unpopular changes when problems or differences of opinion arise.

So how can leaders and non-execs reinvent themselves while addressing deficiencies in the necessary skills, knowledge and key qualities that high performing boards need to succeed?

Successful Boards

One clue as to the best way forward may come from our global research and work with high performing top teams, where one particular country stands out as delivering boards which effectively add value – Australia.

While not exempt from its own top team challenges – Australian boards do not necessarily feature better experience or education than anywhere else in the world – our work does indicate the country’s boards rely far less on friendships or agreeing with the chief executive. Rather, Australia has created a positive culture which enables boards to do the job required of them.

Australia is unique by being big in size, rich in resources, but comparatively small in population. Its people have had to compete in a relatively isolated part of the world, while learning the hard way about making government and business work.

The Australian stock exchange has developed a public ‘name and shame’ list, highlighting individuals with more than five non-exec director roles. Our research backs the validity of this critical position by proposing that non-execs with four or more directorships are incapable of being effective.

In countries such as the US it is not uncommon for non-execs to hold 25 concurrent directorships, while the number can stretch as high as 45 in South Africa. Individuals operating at this level are not treating the board as an appropriate vehicle for mentoring and monitoring.

To be successful they must put in the necessary time needed to learn and understand how they can offer support in line with an organisation’s culture. Too many posts, means too little time. In other words they glance at the figures, make a decision, and walk away with little or no insight into an organisation.

World-wide the norm relies on the long-standing mantra ‘put shareholders and networks first, and let’s have people that support my view and don’t disturb things’. It is highly unlikely a company will fire a CEO for underperforming if they have been playing the expected political games within existing networks to further establish their position. This is a trend that needs to change.

Most directors are conscious of what is wrong but they don’t know how to handle it. They are often blinded by friendships and network relationships.

There are professional processes to search for new members of the board, but we have uncovered that most of these are weighted towards getting the person a chair wants, hidden behind the guise of a fair and level playing field. Search consultants we have spoken to indicate that in London 80% of their headhunting briefs are undertaken merely for appearances’ sake, while in New York this figure rises to an astonishing 95%.

Where Australian boards differ is through their attitudes towards teamwork. While they still exhibit varying levels of ‘mateship’ over the importance of networks or social status, there is a more powerful understanding of boards’ governance responsibilities.

While being aware in their dealings with cultures which place a higher value on these differences, Australia has much to teach the rest of the world about the value of asking difficult questions, and embracing open dialogue to arrive at solutions more quickly and effectively.

It is clear there is no single formula which will work for every organisation but, particularly for businesses operating across several global sectors, the way forward is to build board diversity based on the variety already existing in these markets.

If you are invited to, or are considering taking up a new board position, our work suggests it would be wise to take careful account of the following points beforehand:

If you are external to the organisation:

• Do your homework and consider if you genuinely want to join the board? An invitation is flattering, but is it the right fit for you?

• Are you comfortable working with the Chair of the board, and do they have a positive reputation?

• Can you devote sufficient time to the board? This is a key issue for external directors who hold too broad a portfolio of non-exec posts and don’t devote sufficient time to each

• Does the board have a directors’ induction or development programme?

• Does the board demonstrate a diverse mix of race, gender, skills and talent?

• How will you find the fault lines in the enterprise, which if unattended will do serious harm?

If you are internal to the organisation:

• As a non-exec director, you will be acting in a governance, oversight and advisory role, not making unilateral decisions. Can you put proposals to the board and then evaluate outcomes impartially?

• Consider whether you are willing to pay sufficient attention to comments made by external board members?

• What do you understand about how the organisation really works and can you pinpoint the fault lines in the structure and culture which require attention?

Having both internal and external directors allows a board to become familiar with what an organisation is really like, an intimacy of understanding that can all too often be absent. The critical question all board members should consider is do they have a sufficient independence of mind to make impartial decisions? Before accepting a non-exec post, reflect carefully on your own skills and capabilities. What can you contribute to a particular board?

Once on the board take time to learn and understand your colleagues. Remember you do not have to prove anything. Every board is different and each has its own idiosyncrasies.

In the words of one Australian female director: “The best advice I can give is, you have arrived. Just sit back, observe others and learn. Once you understand the issues, question in the contextually acceptable manner.”

Ultimately, boards have to deal with unique sets of circumstances and, no matter how much procedural governance is put in place, each organisation should be considered a unique entity.

About the Author

Professor Andrew Kakabadse is an internationally-renowned expert in boards, top team management and leadership. He consults and lectures in the UK, Europe, United States, SE Asia, China, Japan, Russia, Georgia, the Gulf States and Australia. He is currently working on a major £2 million global study of boardroom effectiveness and governance practice.

[/ms-protect-content]

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)