By D. De Cremer, G. Houwelingen, C. Ilse, H. Niek, L. Brebels, M. Van Dijke & A. Van Hiel

It is human nature to want to be treated fairly, and nowhere is this more evident than in the workplace. Leaders need to effectively manage the perceived fairness of decision-making for a satisfied, happy, and productive workforce. This article discusses the measures leaders should take to ensure procedural justice in their company.

When company Z decided to implement a new appraisal procedure to evaluate high potentials, the general attitude was one of uncertainty and fear that promotions would be more difficult to achieve. True, the criteria were stricter, making it more difficult to move up the ranks. To their surprise, however, when the new procedures were actually used, employees did not suffer from more distress and none of them expressed a desire to leave the company. Many of them were positive about the new appraisal system and praised the enormous increase in transparency, despite making it hard for them to achieve a quick promotion. Quite often, companies find themselves in situations where they wish to transform their decisions-making procedures, but at the same time fear the negative consequences of destroying their human capital. In this process, it is clear that when transparency, consistency and positive treatment accompanies such big changes, the results are often more positive than ever expected.

Why may this be the case? In such successful situations, leadership takes care of an important human concern: Fairness. To be more precise, they focus on managing the perceived fairness of the procedures used to make allocation decisions; referred to as procedural justice. It is no secret that fairness matters to all of us working in organizations. It is perceived as a basic right for those at the receiving end and a moral obligation for those making decisions. When fair procedures are used during the decision-making process, many positive outcomes emerge. At the individual level, employees feel more satisfied, show more cooperation and citizenship behavior, and retaliatory actions and turnover decreases. At the company level, both employees and customers exhibit more trust in the company, performance levels increase, and a positive reputation of being a thoughtful and moral employer emerges in the market. What makes the employment of procedural justice as part of your leadership style even more appealing is that it carries no financial burden. In fact, it is one of the cheapest organizational means around to promote and maintain employees’ intrinsic motivation. Indeed, contrary to the use of control and monitoring systems, it is inexpensive to provide voice to your employees, treat them in consistent ways and suppress judgmental biases. If the benefits of procedural justice are so obvious and its appeal and effectiveness has been demonstrated in a vast amount of studies during the last 30 years, why then do so many of our organizational leaders refrain from using it? Why then it is that too many of our leaders act as managers with a primary – and sometimes even sole – focus on the delivery of valuable and tangible outcomes rather than to promote harmony and motivation among employees?

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Several reasons can be identified. First, by allowing employees to provide input into the decision-making process, many leaders fear a loss of power and influence. As such, a command-and-control style is preferred to safeguard one’s power position. However, evidence abounds demonstrating that leading by controlling people does not lead to a sense of intrinsic motivation and commitment to the organization. Rather, if commitment is shown under command-and-control conditions it is enforced and therefore not sustainable in the long term. Indeed, once the control mechanism is not present anymore, the displayed commitment will quickly fade away. For this reason, a focus on developing relationships that are experienced as fair and value-driven may in fact reveal much better results – certainly in the long term. Second, although many leaders may be aware that it is important that employees and other stakeholders perceive their decisions as procedurally fair, it remains very difficult for many of them to actually display behaviours that enforce that perception. It is a fact that many organizations fail in educating and training those in management positions to assign importance to the “process” element of decision-making. Rather, their training is focused primarily on assigning importance to the outcomes that decisions reveal. Therefore, hardly any weight is given to “how” they make decisions but only to “what” these decisions reveal. This is a regretful development because much research has demonstrated that employees actually do focus on how decisions are made – sometimes even more so than on the outcomes they receive. Finally, in the minds of our corporate leaders the idea exists that paying attention to the needs and motives of their employees, beyond the outcomes that they receive, is somewhat of an extra leadership task – almost a luxury. Unfortunately, this idea is not shared by the employees leaders need to motivate. Even more so, the ones at the receiving end of a leader’s decision actually consider a focus on procedures and fair treatment as part of a leader’s responsibility and not something that is an extra service. This asymmetry in expectations of how leaders should make decisions sets the stage for poor communication and failure in employing effective motivation strategies. Therefore, companies are advised to make their leaders aware of these insights to prevent that they end up in a situation where both sides hold different expectations and conflicts are bound to happen.

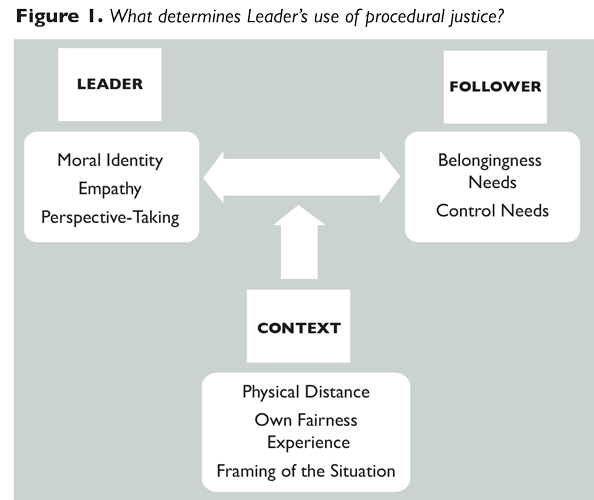

To understand how to train and motivate our leaders to act in procedurally fair ways, it is necessary that we first understand the reasons and circumstances under which leaders are willing to use procedural fairness rules like giving voice, acting consistently across time and situations, use information accurately and provide opportunities to correct decisions. In a series of experimental and field studies, we set out to identify several factors motivating leaders to act in procedurally fair ways. In our search for these factors we adopted a perspective in which leader’s decisions are determined by three types of influences (see Figure 1). Specifically, we looked at the influence of the leader’s orientation, the follower’s needs, and the specifics of the context in which the leader has to make decisions.

A first series of our studies examined the influence that a leader’s value system can have on his or her motivation to take care of procedural justice1. For example, in a field study, we showed that leaders who possess a strong moral identity provided more voice opportunities to their employees. Interestingly, however, this relationship was most pronounced when the context elicited a focus on preventing losses or negative outcomes too. In other words, this effect emerged under conditions when a company’s interests are under pressure the most. This is good news, because under crisis situations where companies face tough competition, the first thing to go out of the window is often a concern with fairness. Our findings do show, however, that in those situations leaders with a strong moral identity will stand up to maintain the use of fair decision-making procedures.

A second series of studies focused more explicitly on the role that the needs of followers play in motivating leaders to treat them in a procedurally fair manner2,3. These studies revealed that particularly followers who express a strong desire to belong to the team or company received significantly more voice opportunities than those who did not express such a desire. This effect was found most strongly among leaders who showed a strong sense of empathy. Thus, leaders who were sensitive to the motivational desires of others seemed more effective in delivering fair treatment to those who care most about it – the ones who want to belong to your company! Another range of studies showed that leaders are particularly influenced by a follower’s desire to belong to their team or company – these employees will be motivated to pursue the company’s interest – but also by their desire to exert control in their job. Specifically, we found that if employees want to belong to the company and are motivated to exert control they received the most voice opportunities. This is again exciting news because it shows that leaders who show empathy and can take the perspective of the employee do provide voice to those who will be of most value to the company: the ones who want to belong, and take control to better do their job.

Finally, organizations are hierarchical in nature so that many organizational leaders have a supervisor. Interestingly, one’s supervisor can be seen as a contextual factor that influences or models the behaviour of the leader at the lower level. Our research, for example, showed that unfair behaviour or fair behaviour by a top manager was modelled by managers one level lower in the company, but particularly so when the actual spatial distance between both of them was low (e.g. their offices were very close to each other)4. When the spatial distance between them was high (e.g. working in different buildings or locations), however, managers at the lower level did not model the unfair behaviour of their supervisor. One reason for this effect to emerge is that spatial distance, but also psychological distance like analyzing events more in abstract rather than concrete ways, helps lower-level leaders to disconnect themselves from experiencing unfair treatment. As a result, they are able to stop themselves from incorporating unfair decision-making procedures as part of their own leadership style.

So, what can we conclude from these studies? First, organizations should carefully scrutinize their work environment so that conditions can be created that prevent examples of unfair decision-making at the top from trickling down, whereas examples of fair decision-making do trickle down. In other words, make it rewarding for companies, particularly their middle-management, to be motivated to look at decision-making in more abstract and distant ways, rather than in concrete and more emotionally involved ways. Such a mindset will prevent unfair treatment at the top, which then translates into unfair leadership behaviour at lower levels. Interestingly, this implication illustrates that middle-management is particularly important to companies when it comes down to making sure that the influence of the right kind of leadership behaviours is picked up at lower levels in the company. In a way, these managers can be seen as instrumental in helping to create the right kind of decision-making culture.

Further, it is crucial that promotions into leadership positions are accompanied by training sessions in which these future leaders develop the necessary skills to enhance their sense of empathy and perspective. Training leaders in ways that they recognize and are open towards the concerns of their workforce will not only help them in making more accurate judgments of when it is most important to employ fair procedures. It will also promote the use of fair procedures towards those who are motivated to work for the company in intrinsically driven ways (i.e. a high need to belong) and with a desire to improve (i.e. a high need for control). Of course, improving skills and a sense of awareness will not lead to the desired results if leaders do not learn the difference between the “how” and the “what” of decision-making. Indeed, leaders need to arrive at an understanding that their accountability with regard to the decisions they take is not only determined by the outcomes they allocate to others, but, under some circumstances, even more so by how they make those allocation decisions. Too often, an outcome-based focus – that only results matter – is fostered among management. It is a company’s responsibility to make clear – as part of their value system – that the coin of decision-making has two sides and that both the “what” and “how” need to be managed. In this view, the development of the values and moral identity of one’s leaders is a task that cannot be ignored, and should be central in every company’s communication strategy. After all, only managing one side of the coin makes a company blind to its own weaknesses: if one’s values are never spelled out and thus never trained, derailment rather than future success looms at the horizon.

About the Authors

David De Cremer is the KPMG chair of Management at Judge Business School, Cambridge University and a visiting professor at London Business School. He was elected the most influential economist in the Netherlands in 2009-2010. His research and consultancy interests are in the areas of leadership, behavioural economics and business ethics, incentives and bonuses, trust and organizational justice, Email:

ddcremer@london.edu

Gijs van Houwelingen is PhD-candidate in Behavioral Ethics at the Rotterdam School of Management and the Erasmus Centre for Behavioral Ethics, Email: gijsvanhouwelingen

@rsm.nl

Ilse Cornelis works as a researcher and lecturer for the Centre for Family Finance Policy and Research (CEBUD) at Thomas More University College, Email: i.cornelis@thomasmore.be

Niek Hoogervorst is Assistant Professor in Ethical Leadership at the Rotterdam School of Management and the Erasmus Centre for Behavioral Ethics, Email: nhoogervorst@rsm.nl

Lieven Brebels is Assistant Professor of Organizational Behaviour at KU Leuven, Centre for Business Management Research, Email: Lieven.Brebels@kuleuven.be

Marius van Dijke is Scientific Director of the Erasmus Centre of Behavioral Ethics at Rotterdam School of Management (Erasmus University Rotterdam) and professor of Behavioral Ethics at Nottingham Business School, Email: mvandijke@rsm.nl

Alain Van Hiel is a professor in Social and Political Psychology at Ghent University, Email: alain.vanhiel@UGent.be

References

1. Brebels, L., De Cremer, D., Van Dijke, M. & Van Hiel, A. (2011). Fairness as Social Responsibility: A Moral Self-regulation Account of Procedural Justice Enactment. British Journal of Management, 22(1), 47-58.

2. Cornelis, I., Van Hiel, A., De Cremer, D., & Mayer, D. (2013). A leader perspective on procedural fairness: The role of follower belongingness needs and leader empathy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 605-613.

3. Hoogervorst, N., De Cremer, D., & van Dijke, M. (2013). When do leaders grant voice? The role of followers’ control and belongingness needs in leaders’ enactment of fair procedures. Human Relations, 66(7), 973-992.

4. Houwelingen, G., van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (in press). Fairness Enactment as Response to Higher Level Unfairness: The Roles of Self-Construal and Spatial Distance. Journal of Management.

[/ms-protect-content]