By Klaus-Peter Wiedmann, Evmorfia Karampournioti and Nadine Hennigs

Storytelling has become an essential element of the business environment to deliver information, manage conflicts, support team building processes, and create emotional bonds with a company’s stakeholders. This article will explain how you can effectively adapt the storytelling approach from a consumer brand perception.

“The best brands are built on great stories.” – Ian Rowden, Chief Marketing Officer, Virgin Group

Introduction

Throughout the ages, all aspects of life in societies and cultures have been influenced by stories that form human values and dreams. As the oldest and most effective form of passing knowledge between generations, the art of storytelling represents the way people perceive and interpret past, present and future events. Instead of facts, stories are easy to remember and live on telling and re-telling. In our everyday life, the success of storytelling is widely apparent and becomes visible in music and books, movies and media, architecture, paintings and religion. Besides, storytelling has become an essential element of the business environment to deliver information, manage conflicts, support team building processes, and create emotional bonds with a company’s stakeholders. Particularly, in a brand management context, storytelling is supposed to be a valuable instrument to positively affect consumer brand perception and related behaviour. The aim of this article is to provide insights in the effective adaption of a storytelling approach against the backdrop of value creation and consumer brand perception. Based on the main dimensions of storytelling such as the plot, the story architecture, specific turning points, the experience of a conflict, the interaction of characters, the text style, the narrative form and the key lesson, it will be shown how a credible story has to be arranged in relation to the core elements of a brand.

The History of Storytelling

The historical origins of storytelling cannot be traced to a particular time in the past, nevertheless, it can be stated that the desire to hear and tell stories has existed even before humans had the capacity to speech: Cave paintings are the earliest form of story-telling in a time long before languages and writing existed. Stories about past events and warnings of dangers and risks were painted on cave or rock walls to entertain and educate children. Over the times, the development of languages led to the oral tradition of storytelling that spread stories between groups of people through word-of-mouth at e.g., tribal events and campfires. Passing from generation to generation, stories in terms of myths, legends, fairytales, paintings or songs about heroic adventures, experiences, dangers, rituals and natural events were told and retold. Through stories, humans tried to explain the inexplicable and find a reason for incidents in their past and present world. As stated above, before people had the ability to read and write, oral stories represented not only entertainment but also common knowledge and education: Stories transported wisdom and beliefs as part of a cultural heritage and preserved historical record. Reasoning the importance of storytelling, the ability to effectively tell stories was a valuable skill and vest power and social influence. Storytellers had a key role in their community and kept important knowledge alive by inspiring their audience.

Even in our modern times, the power of story-telling is an important part of everyday life and business contexts: Stories transport content and messages better than sheer facts. Referring to the connection between consumers and brands, a creative, authentic story that is told and shared allows the creation of an individual bond that represents a key success factor in a competitive environment. Particularly in marketing and management, storytelling has become increasingly of interest to create desirable images and foster consumer-brand-interaction.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

The Secret to Storytelling – Engaging Hearts and Heads of Your Audience

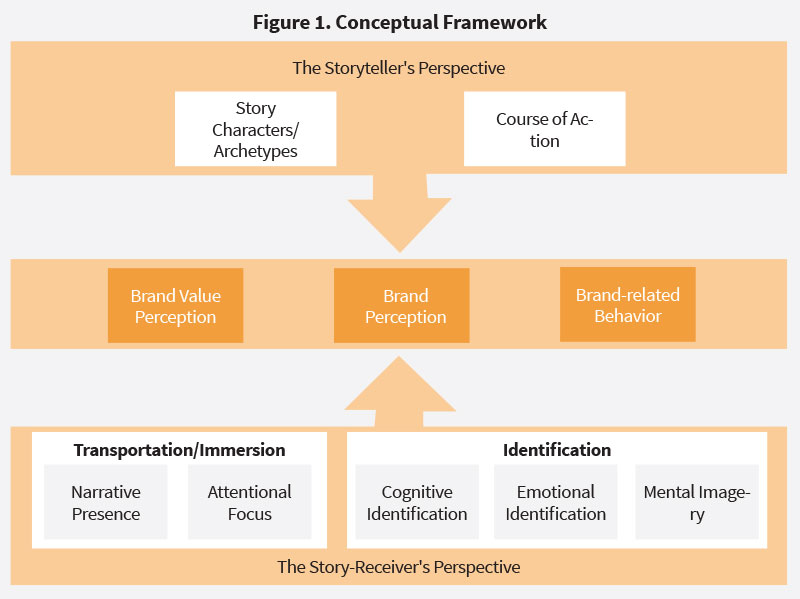

Telling tales as a trump card in brand building and brand communication in general, addresses the emotional world of a consumer and aims to construct a particular mental image/representation of a brand (Gálvez, 2016). Despite the numerous advantages and the increasing popularity of storytelling in business and research areas, little is known about the fundamental elements and underlying mechanisms of successful stories. Hence, creating and telling a persuasive, emotional, experienceable and credible story which creates sympathy, closeness and identification between consumers and brands, necessitates a holistic framework that considers both perspectives – the storyteller’s and story-receiver’s as appears in Figure 1 (see Figure 1 below (van Laer et al. 2014).

How Storytellers Rule the World

Referring to the storyteller, creating substantive story elements and building a harmonised narrative is one of the major hurdles. Story characters can initially be identified as essential components, since every story needs a protagonist – possibly even a hero – who is a focal point of a story and with which the audience can identify. Usually, the protagonist goes through a process of transformation within a story. This process is commonly accompanied by an opponent (antagonist) representing and supporting the contrary standpoint of the protagonist. Nike for example, sees an inner hero in everyone, and frames its advertisements around challenging oneself to take action on life’s most impossible and unimaginable challenges. The endless human potential, as an important part of the protagonist’s characteristics, is continuously conquering its antagonist that is represented by one’s weaker self. “Just Do It” is no longer a trivial motto or phrase, but a movement symbolised by a dynamic attitude toward life.

Beyond the characters, that can be embodied by different archetypes (e.g., hero, rebel, jester etc.), the course of action constitutes a key element of every successful and compelling brand story. Segueing from an initial situation to a rising action and turning point of the protagonist’s experience (e.g., the ugly duckling becomes a beautiful swan), occurring conflicts unknot during the falling action and bring the story to a final resolution with an (hopefully) overall satisfaction at the end. Structural story elements can be motives, goals, problems, conflicts and their solutions and transformations that increase the emotional involvement (Escalas et al. 2014), depending upon which missions, visions and values brands need to effectively convey to the audience.

Being Hooked by a Story – The Story-Receiver’s Perspective

Referring to the consumption of the story and hence to the perspective of the story-receiver, transformative effects can occur through an immersive transportation into narratives. A narrative is not simply read or seen, but is literally experienced through the immersion into a story, leading to long term impacts on consumers’ perception and valuable benefits for brands (van Laer et al. 2014). Narrative transportation occurs “whenever the consumer experiences a feeling of entering the world evoked by the narrative” (van Laer et al. 2014, p. 798) and acts as a mediator for attitudes, brand choice and behaviour (Escalas et al. 2004). Simply said, narrative transportation combines affective and cognitive processes, by which recipients get mentally immersed into the world of the story or take a journey into the story-world (Escalas et al. 2004; Green & Brock 2000). Throughout the journey into the brand cosmos, positive feelings are caused that prevent critical scrutiny of the brand (Escalas 2004). Due to transformative experiences through narrative transportation, compelling stories have long term impacts on consumers’ perception and behaviour. The brand Red Bull for example, has made its energy drink known by stories related to extreme sports. Through its effective storytelling, consumers get immersed into a world full of adventures in which critical thoughts such as the high sugar content (which is in contrast to the sporty image) can be suppressed.

From a scientific point of view, numerous explanations for the phenomenon of transportation exist. Most of the research emphasises on the feeling and the experience of being present in the described story-world (Escalas et al. 2004; Lessiter et al. 2001; Busselle & Bilandzic 2009; De Graaf et al. 2012). The audience gets immersed into the whole story environment and responds cognitively as well as emotionally to the perceived events (Sestir & Green 2010). Often referred to as narrative presence, this process is accompanied by the entry into time and space of the story contingent upon a loss of reality or one’s own self-perception (Hall & Bracken 2015).

Consumers’ attentional focus constitutes a central prerequisite for narrative presence and is closely intertwined with narrative transportation. Research on transportation into narrative worlds determine that narrative transportation is comparable to the experience of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Green 2004), which is “conceived as a complete focus on an activity accompanied by a loss of conscious awareness of oneself and one’s surroundings” (Busselle & Bilandzic 2009, p. 324). As a result, fully concentrated story-receiver with a shifted reality perception, relocate their attention and awareness from the immediate physical and social space toward the world of the story environment (Busselle & Bilandzic 2009). Hence, the audiences “[…] attention is completely absorbed by the activity [and individuals] stop being aware of themselves as separate from the actions they are performing” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 53).

Seeing in the Characters’ Eye – Identification Between Audience and Characters

While being transported, immersion processes allow consumers to identify with story characters and brands and increase the perceived plausibility of narratives. Throughout the absorption into a character’s emotional state and personality (Cohen, 2001; Slater & Rouner, 2002) the audience experiences “an imaginative process through which an audience member assumes the identity, goals, and perspective of a character” (Cohen 2001, p. 261). Emotional and cognitive states and relationships to the characters occur, whereby feelings, emotions, memories and thoughts can be easily recognised and understood (Cohen 2001; Oatley 1999; Green et al. 2004). In advanced conditions of identification, denoted as mental imagery, consumers ideally get entirely absorbed and thus cognitively and emotionally became a part of the story world. By “seeing in the eye”, “hearing in the head” and “imagining the feel of” the story characters, consumers experience themselves as acting and integral story components, hence, occurring events, motives and attitudes are interpreted from the character’s perspective (Busselle & Bilandzic 2009), which is created according to the brands values, beliefs and vision.

If brands successfully manage the implementation of the above mentioned elements, there is no obstacle to a credible story, which transfers the brand values to its audience and effectively impacts brand perception and brand-related behaviour. In a broader sense, audience members become part of a community within the story and meet their social needs. For this purpose, brands increasingly take advantage of the interactive nature of social media platforms and enable consumer to co-create and retell stories. Social media offers a lot of stages for story-telling and enables brands to mingle with people and close virtual friends. TOMS shoes for example, asked its audience to go barefoot for one day and to share their story and barefoot experience via social media platforms. Since shoes are part of a journey on every single day TOMS makes use of this campaign to demonstrate how difficult a shoeless life could be. Two major goals of this campaign were to raise awareness about worse living conditions of people in poorer countries, and to charge the brand and its products with social and philanthropic values. Consumers hence, who buy a pair of shoes and simultaneously donate a pair to people in poorer countries, get the feeling of doing something good with their purchase decision and perceive themselves as a rescuing hero within the brand’s story world.

Conclusion and Outlook: Tell, Don’t Sell

To sum up, successful storytelling goes far beyond incoherent stories, metaphors and rash social media posts. Rather, it is a matter of telling comprehensible and credible stories that immerse consumers into the brand’s world of values, and specific mission and vision. Brands and companies are full of precious stories that need to be told. Therefore, businesses necessitate identifying the core elements and emotional heart of their individual story as a basis of their entire brand communication. Hence, as a part of the entire brand community, consumers are able and willing to retell compelling and immersive stories and to convincingly spread the message throughout the whole world.

“After nourishment, shelter and companionship, stories are the thing we need most in the world.” – Philip Pullman

[/ms-protect-content]About the Authors

Prof. Dr. Klaus-Peter Wiedmann is a Full Chaired Professor of Marketing and Management and the Director of the Institute of Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. He has many years of experience as a management consultant and top management coach, and takes a leading position in different business organisations as well as public private partnerships. Main subjects of research and teaching as well as consulting are: Strategic Marketing, Brand and Reputation Management, Corporate Identity, International Marketing and Consumer Behaviour.

Prof. Dr. Klaus-Peter Wiedmann is a Full Chaired Professor of Marketing and Management and the Director of the Institute of Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. He has many years of experience as a management consultant and top management coach, and takes a leading position in different business organisations as well as public private partnerships. Main subjects of research and teaching as well as consulting are: Strategic Marketing, Brand and Reputation Management, Corporate Identity, International Marketing and Consumer Behaviour.

Sc. Evmorfia Karampournioti is a Scientific Research Assistant at the Institute of Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. Her main subjects of research and teaching as well as management consulting are: International Marketing, Marketing Strategy, Brand Management and Consumer Behaviour

Sc. Evmorfia Karampournioti is a Scientific Research Assistant at the Institute of Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. Her main subjects of research and teaching as well as management consulting are: International Marketing, Marketing Strategy, Brand Management and Consumer Behaviour

Dr. Nadine Hennigs is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. Her main subjects of research and teaching as well as management consulting are: International Marketing, Marketing Strategy, Consumer Behaviour and Luxury Brands.

Dr. Nadine Hennigs is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. Her main subjects of research and teaching as well as management consulting are: International Marketing, Marketing Strategy, Consumer Behaviour and Luxury Brands.

References

• Busselle, R., Bilandzic, H. 2009. Measuring Narrative Engagement; Media Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 321-347.

• Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience, New York.

• Cohen, J. 2001. Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audiences With Media Characters; Mass Communication & Society, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 245-264.

• De Graaf, A., Hoeken, H., Sanders, J., Beentjes, J.W.J. 2012. Identification as a Mechanism of Narrative Persuasion; Communication Research, Vol. 39, No. 6, pp. 802-823.

• Escalas, J.E. 2004. Imagine Yourself in the Product. Mental Simulation, Narrative Transporation, and Persuasion, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 3748.

• Escalas, J.E., Moore, M.C., Britton, J.E. 2004. Fishing For Feelings? Hooking Viewers Helps!; Journal of consumer psychology, Vol. 14, No. 1&2, pp. 105-114.

• Gálves, C. 2012. 30 Minuten Storytelling, 4. Auflage, Offenbach.

• Green, M.C., Brock, T.C., Kaufman, G.F. 2004. Understanding Media Enjoyment: The Role of Transportation Into Narrative Worlds; Communication Theory, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 311-327.

• Hall, A.E., Bracken, C.C 2015. I Really Liked That Movie. Testing the Relationship Between Trait Empathy, Perceived Realism, and Movie Enjoyment; Journal of Media Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 90-99.

• Lessiter, J., Freeman, J., Keogh, E., Davidoff, J. 2001. A Cross-Media Presence Questionnaire: The ITC-Sense of Presence Inventory; Presence, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 282-297.

• Oatley, K. 1999. Meetings of minds: Dialogue, sympathy, and identification, in reading fiction; Roetics, Vol. 26, No. 5-6, pp. 439-454.

• Sestir, M., Green, M.C. 2010. You are who you watch: Identification and transportation effects on temporary self-concept; Social Influence, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 272-288.

• Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. 2002. Entertainment–education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 173-191.

• Van Laer, T., De Ruyter, K., Visconti, L. M., & Wetzels, M. 2014. The extended transportation-imagery model: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of consumers’ narrative transportation. Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 40, No. 5, pp. 797-817.